4 minute read

Critiquing Modernist Architecture without Solutions

3 - The continuous monotony

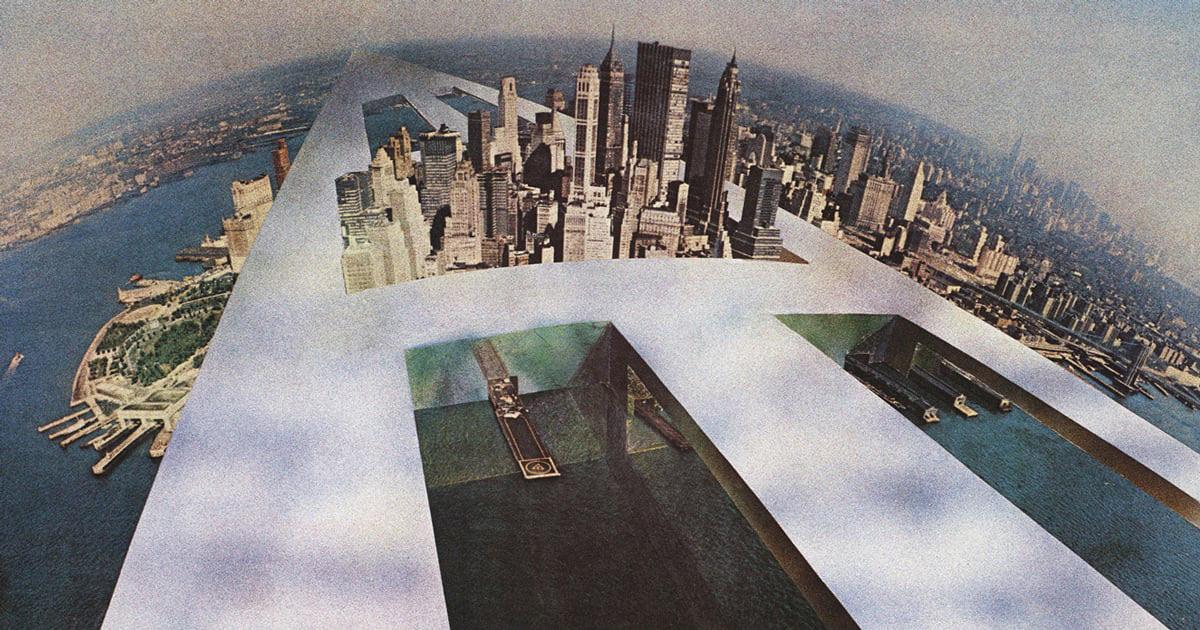

The Continuous Monument – An Architectural Model for Total Urbanization, is Superstudio’s most famous project. (Figure 18) This design was realized in 1969, with the intention to propose a uniform, transparent structure that extends over the landscape, wrapping up the city landmarks, and encasing it in this generic, white continuous façade.

Advertisement

By revisiting their design principles of not being constrained by any matter / space regulations, the Continuous Monument can be seen as another direct critique towards modernist architecture : With the building itself being an allegory of every trait of modernism, with its bright taint painted all over, its contrast with the landscape is obvious. Though it does not differ so much with the landmarks of the city it encases, its odd shape makes it stand out.

While this disdain for the new society goals is clear, this shows how redundant their projects have become; Although this project is Superstudio’s signature and displays behind the architect’s eye where society is headed to if it keeps sticking to this idea of building “machines for living, with technology draining all the qualities of the landscape”, the architect’s duty is to propose a solution to respond to this issue. As stated by Juhani Pallasmaa (2019, p. 11) in The Eyes Of The Skin, “The essential mental task of architecture is accommodation and integration. Architecture articulates the experiences of being-in-the-world and strengthens our sense of reality and self; it does not make us inhabit worlds of mere fabrication and fantasy.” where the Misura furniture collection was strong conceptually speaking as its physical representation could show its purpose by being experienced by their users, the Continuous Monument only depicts an unachievable and utopian project, which goes at the opposite of the dramatization that Superstudio wanted to convey. If it looks unbuildable, this dreadful idea is not to be feared.

As their experience as architects could raise all these issues, this perception is not accessible to everyone, unless it is lived and perceived in space and time by the population these society problems affect. The architect’s eye is fierce enough to spot flaws at different scales and various corners, but its depiction cannot be raised only by visual means, a response needs to be provided. As they are designers, in the example of Superstudio, their creativity could have been explored deeper to create a solution to address these conditions from a different perspective. As stated by Nigel Coates (2012, p. 55-56) in Superstudio, From Life–Supersurface: The Encampment : “The London-based avant-garde group Archigram, founded in the 1960s, avoided building anything, some say successfully, with the implication that to build would rob their work of its visionary power.” if the Italian architects’ signature were to follow Archigram’s scheme, the precedent observations in this essay could unveil that not building any of these projects reflects their lack of means to respond to those issues raised in their projects.

Conclusion

How to fight architecture with architecture ? Superstudio answered in a clever way to this question with their design philosophy. The versatility of their principles of “not designing but to some extent” raised all their points by borrowing elements of the society’s current movements (such as pop art and modernism) to change the perception of architecture : how to make a bold statement by carefully integrating art, how to “not tease” a proposal by having it never built, and how to switch the focus of the architect from the exterior to the interior.

They did not design these projects for the purpose of painting a white stain on a black background, or for the sake of responding to a thesis by an antithesis; their anti-architecture raised various flaws not only in modernism at that time, but also in the way society worked at that time. They designed as a statement, and in some scenarios, for a pure human experience. Their works of art were catching the right elements to highlight the issues Italy was facing. As Architecture shapes society, so did Superstudio’s legacy. And as society changes, so does the extent of their critiques.

Their perception of the profession still carries on today, as they have proven that a statement can be strong even conceptually, that architecture’s strength does not lie only considering time, matter and space, but that the profession’s perception has broadened thanks to the avant-gardists’ principles. Their vision of architecture is still explored nowadays, where it is seen to question how to solve the contemporary’s crisis, social issues, and to which fields the architect can have an influence. This extends the responsibility of architecture into shaping society and enlarging its scale impact.

Word count : 3030

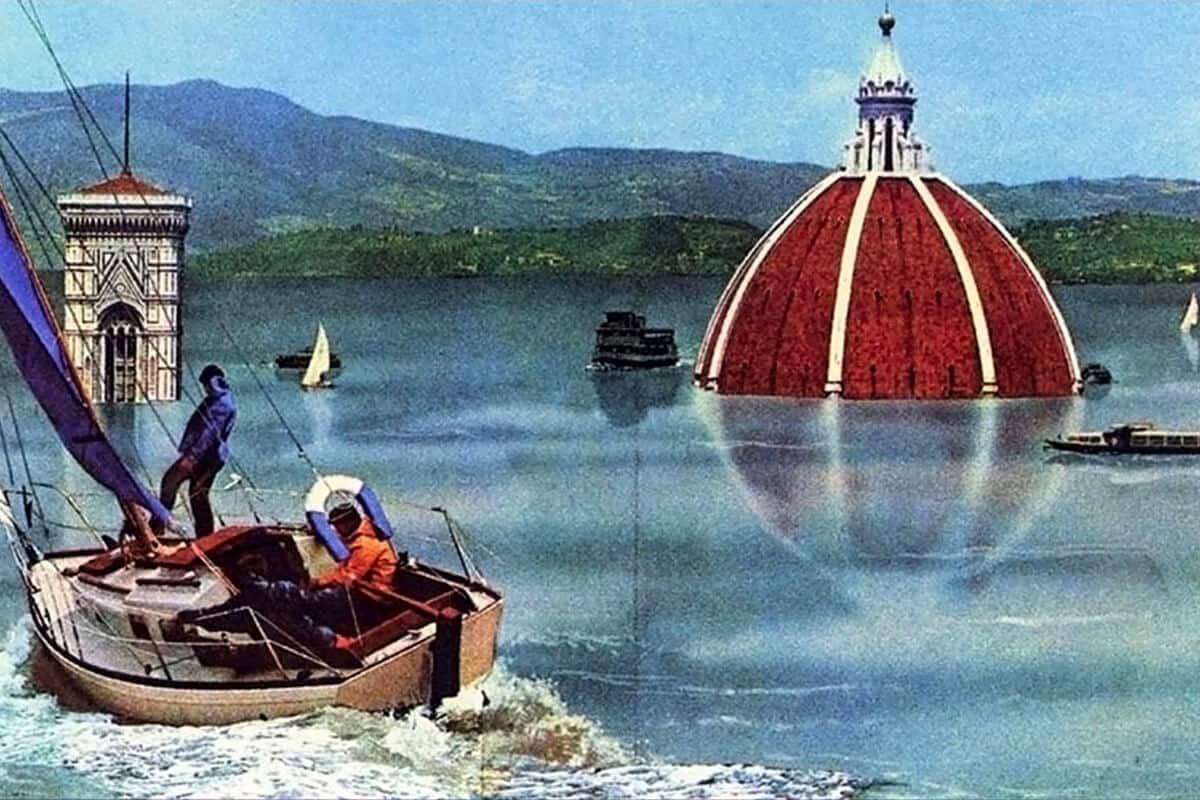

Superstudio's collage. Rescuing Florence, in Italy. Under today's interpretations, a different message appears, far away from the designers' first intention.

- Braham, W.W. (2007) Rethinking technology: A reader in architectural theory.

- Bru, S. (2012) “Given the popular,” in Regarding the popular: Modernism, the avant-garde, and high and low culture. Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 8.

- Catina, A. (2021) Aleks Catina on Superstudio 'migrazioni'superstudio 'migrazioni' Civa, Brussels, Belgium 15 January to 16 May 2021: ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly, Cambridge Core. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/ core/journals/arq-architectural-research-quarterly/article/aleks-catina-on-superstudio-migrazioni-superstudio-migrazioni-civa-brussels-belgium-15-january-to-16-may-2021/C06E957682FDE348C65EE3FDEBCFB7EA (Accessed: April 20, 2023).

- Chirumbolo, P. and Moroni, M. (2014) “Superstudio Double-Take: Rescue Operations in the Realms of Architecture ,” in 'Neoavanguardia' Italian experimental literature and arts in the 1960s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Coates, N. (2012) “Superstudio, From Life– Supersurface: The Encampment , 1969.,” in Narrative architecture. London: Wiley-Academy, pp. 55–56.

- Deamer, P. (2014) “Manfredo Tafuri, Archizoom, Superstudio, and the critique of architectural ideology,” in Architecture and capitalism: 1845 to the present. London: Routledge, p. 139.

- Fabbrini, S. (2015) “Hidden Architecture: Superstudio's Magic Box,” Pidgin Magazine Princeton School of Architecture, March, pp. 8–21.

- Lang, P. and Menking, W. (2003) “Superprojects: Objects, Monuments, Cities,” in Superstudio: Life without objects. Milano: Skira, p. 166.

- Pallasmaa, J. (2019) The eyes of the skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chichester: Wiley., pp.11-70-72.

- Superstudio (1970) “[hidden architecture],” Design Quarterly, (78/79), p. 54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/4047407.

- Superstudio (2017) Superstudio: Misura Series, DOMUS. Domusweb. Available at: https://www.domusweb.it/en/from-the-archive/2011/07/21/-superstudio-misura-series.html (Accessed: April 23, 2023).