10 minute read

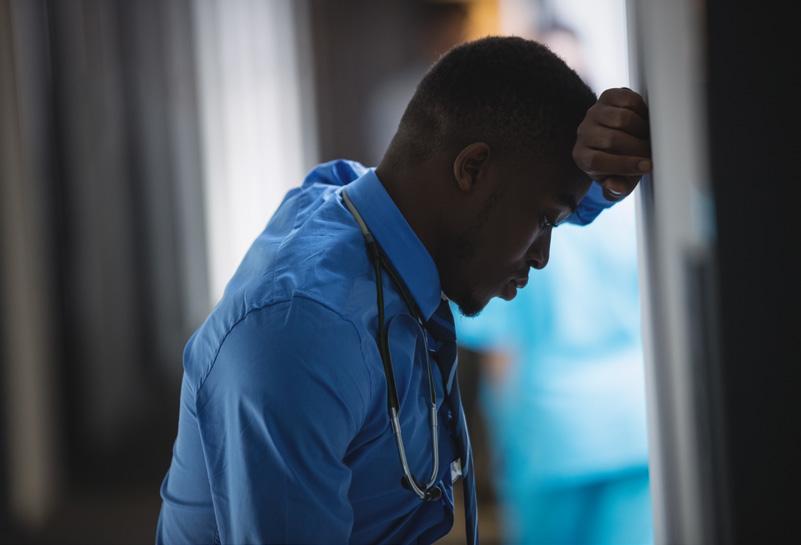

PHYSICIAN WELLNESS

“Healthy citizens are the greatest asset any country can have.” Sir Winston Churchill

BY DOUGLAS P MURPHY, MD

Advertisement

When the opportunity to write an article on physician wellness for CCMA’s Central Coast Physicians (CCP) for arose, I was immediately moved by the opportunity to further explore the issue knowing its importance in light of profound and ongoing changes in medicine now complicated immensely by a global pandemic. However, it became clear to me that the depth and breadth of the issue would not in my estimation permit a just presentation in a single article. Hence, this is the first of a series of articles for Central Coast Physicians magazine that will address the multifaceted, complex, and profoundly important issue physician health and wellness.

The issue of physician wellness has grown immensely in importance over the last decade or more, and with the COVID-19 pandemic still raging internationally, perhaps even more so. This is due to wellness’ critical impact not only on the lives of physicians and their families, but also on the ability of healthcare systems to function optimally and provide the best possible care to patients. A growing body of research and international attention is mounting because of the belief amongst institutions and stakeholders that it takes a healthy doctor workforce for health systems to operate effectively in the service of providing high quality patients care.

However, since the “Golden Era of Medicine”, a time when the medical profession and the institutions it controlled enjoyed especially high public regard, ended in the mid-late 20th century, physicians have sought to serve patients amidst a protracted and unprecedented transition effecting virtually every aspect of medicine. The necessity for this change has at its foundation unsustainably rising healthcare costs. In 1960, healthcare costs in the United States as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) were 5%; by 1980 these costs grew to 8.9% but by 1992 they had risen to 13.1% of GDP, respectively. The reasons for these increases are beyond the scope of this article. However, this growth in healthcare costs have broadly been recognized as unsustainable driving the need for change.

Efforts at reforming the healthcare system began with the Clinton Administration’s efforts to pass health care reform legislation the early 1990’s which were largely unsuccessful. However, momentum from these efforts led to the “first wave” of healthcare reform and the advent of managed care. A burgeoning bureaucracy was created to manage the provision of medical care and spending and with it a significant portion of physicians’ freedom, autonomy and earnings shifted from doctors to the federal bureaucracy and private insurance administration. Yet costs did not decline nor did their increase slow. By 2008 healthcare spending was 16.3% of GDP and still growing. This was followed by the Affordable Care Act in 2010. So-called Obamacare created a new set of values, principles, and institutions, largely theoretical, with the novel goal to improve quality of healthcare while containing costs.

This is recognized perhaps most singly in, “The Triple Aim: Care, health, and cost” (Berwick 2008). The Triple Aim stated, “Improving the US health care system requires simultaneous pursuit of three aims: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.” Basically, the goal was to get more with less through efficiencies derived from technology, economies of scale and better management of resources. Despite these efforts, healthcare costs continued to rise. By 2018, healthcare costs grew to 17.7% of GDP.

During this protracted period of radical changes in healthcare, the practice of medicine was beset with shifting values and principles, goals and priorities, and overseen by changing sets of rules and institutions. Since the early 1990’s the practice of medicine had been pressed by powerful forces in efforts to more equitably manage medical care and more recently to implement

Wellness Action Item #1: Exercise

Whether you are an experienced gym enthusiast, a runner or active in a healthy aerobic sport, there is no single act that one can commit to than voluntary physical exercise in support of personal health and wellness. Physical exercise has been described as the best antioxidant supplement in existence (Kravitz 2009, Ristow 2009). As you are well aware, the American Heart Association recommends, “Get at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous aerobic activity (or a combination of both), preferably spread throughout the week” (AHA 2020). A helpful 1-page pdf handout may be downloaded for your practice to give to patients in AHA 2020 refernce-2, below. We know this. We teach this to our patients. But do we do this?

If you are just beginning an exercise regimen, consider beginning by simply doing what you can. Try to identify distractions and resistances to “getting out there” and consider them in comparison to the emotional and physical benefits that await you upon embarking on a practical exercise regimen. Of course, always check with your own doctor first if there is any question

the Triple Aim. Meanwhile, doctors were seeing a decrease in their independence and autonomy while being progressively aggregated into systems of care that limited what they entered medicine to do: engage and provide excellent care for patients. Physicians as a group are at best a body of professionals selected to attain to the highest ethical and professional standards in medicine. Administrative burdens and the time spent engaging Electronic Medical Records became significant obstacles to engaging and providing quality care to patients, the heart and soul of the practice of medicine.

However, in time it became understood that rapid and ongoing changes to the practice of medicine (e.g., increased administrative burdens and growing bureaucracy, the growth of electronic medical records, remuneration issues and conflicts between the needs systems and patients) are all potential threats to the health and wellness of physicians. Terms like “physician wellness” and “burnout” became widely discussed principles for the first time in the profession. A growing body of research is demonstrating that the result of physicians’ stress, fatigue, burnout, depression, and psychological distress, necessarily have serious negative affects on the health-care systems and patient care. Hence, physician wellness has become a prominent worldwide healthcare issue because poor physician health and wellness has been shown to lead to state that undermines the goals of healthcare reform and the Triple Aim.

In 2014 Bodenheimer and Sinsky published their seminal article, “From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider.” The authors posited the Quadruple Aim recommending that the Triple Aim be expanded by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff (Bodenheimer 2014). Hence, physician wellness became a fundamental consideration in efforts to achieve healthcare reform and the goals of the Triple Aim. To succeed in developing a costeffective, high quality healthcare system, ensuring the health and wellness of physicians would be fundamental to process of succeeding in this goal. Finally, the state of physician’s wellness was seen as being to the benefit of the healthcare system and ultimately to patients.

What is physician wellness? What is burnout? Definitions abound and research on this subject is rife with a lack of consensus as to precisely what constitutes the construct of physician wellness. A conceptual definition of physician wellness has been proposed by Brady et al., “Physician wellness (well-being) is defined by quality of life, which includes the absence of ill-being and the presence of positive physical, mental, social, and integrated well-being experienced in connection with activities and environments that allow physicians to develop their full potentials across

References Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 2008 May/June; 27(3):759-769. Bodenheimer T and Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. The Annals of Family Medicine November 2014, 12 (6) 573-576. Brady KJS, Trockel MT & Khan CT, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systemic review of its definition and measurement. Academic Psychiatry, 2018 Feb;42(1):94-108. Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Developmentofanewresiliencescale:theConnor-DavidsonResilienceScale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82. Tait D. Shanafelt, MD; Sonja Boone, et al. Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance Among US Physicians Relative to the General US Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. August 20, 2012. West CP, Dyrbye LN and Synsky C, et al. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e209385. Further references are available upon request.

persona and work-life domains” (Brady 2017). Closely linked to Physician Wellness is the opposing and widely recognized concept of burnout, and the health and wellness promoting concept of resilience. Burnout has been described as a syndrome characterized by a loss of enthusiasm for work (emotional exhaustion), feelings of cynicism (depersonalization), and a low sense of personal accomplishment (Tait 2012). Resilience is defined as the collection of personal qualities that enable a person to adapt well and even thrive in the face of adversity and stress (Connor 2003). Recently West et al have showed that “Resilience is inversely associated with burnout symptoms.” Hence, developing resilience is central to the development of physician wellness. These are theoretical and complex constructs which will require ongoing research and application to develop practical and actionable elements making it possible to optimize physician resilience and wellness and minimize burnout.

If physicians are going to thrive in this new era of medicine, physician groups, institutions and healthcare systems will have to work together to optimize the attainment of health and wellness. Without this, the worthy goals of the Triple and Quadruple Aims will not be realized, and patient care will ultimately suffer. Future editions of this series will look at the history of health and wellness from ancient to modern conceptions, and the broad range of ideas related to the constructs of physician wellness, resilience, and burnout. The series will discuss major changes in the healthcare industry that positively and negatively effect physician health and wellness, highlighting those supporting improvement of physician wellness. It will explore consequences of extremes on the continuum of burnout, specific practices that can be employed for milder cases, resources available for moderate and interventions available for more severe cases. The series will explore how physicians can overcome denial (rampant on this issue among physicians) and recognize symptoms of burnout within themselves. Moreover, it will seek to identify practical and actionable lifestyle practices that may be of benefit to our physician readers in seeking to improve their own personal health and wellness. Finally, the series would be remiss if it didn’t address the overwhelming impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the resultant world shutdown and massive effect it has had on healthcare systems, and how this is and is expected to affect medical systems and the health and wellness of physician in the future.

Thank you for your time in reading this article. It is my hope that as a whole this series will provide information and practical principles and tools that will aid our physician members in attaining their own personal optimal health and wellness. as to whether a health issue might limit you safely exercising. One way is to start with a 10-minute walk outside or your home once a day or as many times as you are able. Then begin to walk alternating between jogging gently and walking for 1-minute each or at whatever interval you are comfortable with. Increasing your walking to jogging ratio eases the intensity of the exercise. Emphasis should be on consistency – get out there – and on enjoying the experience. Notice how you feel afterwards. Better? I hope so. Overexerting is often a significant problem with beginning an exercise regimen. Our egos may get in the way here. When we begin an exercise regimen too quickly our deconditioned bodies are hit hard with oxygen debt leading to an overwhelming drive to breathe deeply associated with feeling of breathlessness. This feels terrible. At a subconscious level, it is the equivalent of giving your brain stem a “punch in the nose;” it is painful at a deep psychological level. It is no wonder many of us avoid exercise. I did for years. If we emphasize frequency and enjoyment of the experience over the intensity of the exercise, we feel better afterwards and are much more likely to want to persist and develop those weekly exercise habits that offer so much in the way of emotional and physical health. More on this in a future article.