5 minute read

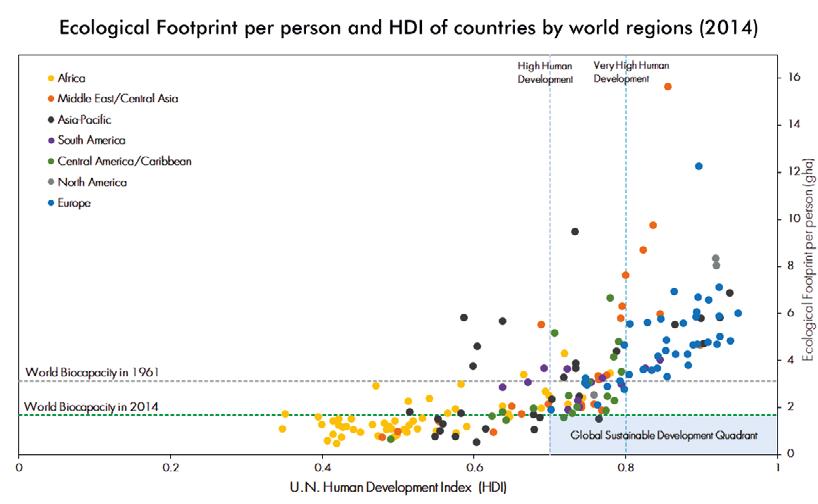

Figure 2: The combination of Human Development Index and Ecological Footprint

from Transdisciplinary Learning for Sustainable Development: Experience in Course and Curriculum Design

Figure 2: The combination of Human Development Index and Ecological Footprint reveal global socio-economic disparities (Source: Lin et al. 2018, 58)

Already half a century ago, the “Meadows report”, The Limits to Growth, predicted:

“If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.” (Meadows et al. 1972, 23).

Since then, various milestones in the literature have created broad awareness of the major global challenges, including suggestions on how to deal with them. For example, Our Common Future (WCED 1987); the UN “Rio” Conference on Environment and Development 1992 with its Agenda 21; the United Nations Millennium Declaration and the Millennium Development Goals or MDGs (UNGA 2005); and 2052: A global forecast for the next forty years (Randers 2012). In September 2015, the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development was approved by 193 member states (UNGA 2015). Entitled “Transforming our World”, it contains the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and is thus the globally accepted political agenda for SD in the coming years.

Knowledge on the unsustainability of impending developments has been around for half a century, with a first early warning published in 1972 “(The Limits to Growth)”, followed by several other milestones in literature, many of them based on research. The latest milestone – the UN 2030 Agenda with its 17 SDGs, is the globally accepted political agenda for SD in the coming years.

I need constant growth!

Well, we call it “cancer” …

Cartoon 2: Limits to Growth – how to convince a tumour that what it considers a great success is in reality tantamount to suicide? (Illustration: K Herweg)

1.2 The UN Understanding of “Sustainable Development” and the Role of Science

The UN understanding of “Sustainable Development” (SD) serves as an orientation, postulating a development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987). SD is a long-term, optimistic mission statement of societal development that puts people and their needs, capabilities, and actions at the centre. It simultaneously strives for inter- and intra-generational, sociocultural, and economic equity and justice, and to maintain the functions of nature and the services it provides to society.

These tasks require contributions at all levels of decision-making, from the individual to the global. Consequently, participation is one of the core principles of the vision. But SD is a fuzzy target, and solving complex problems is a continuous process of negotiation to identify trade-offs (compromises); to balance and harmonize multiple ecological, sociocultural, and economic interests; and to solve target conflicts in consensus and peacefully. A precondition of this process is that all actors are empowered with the necessary knowledge, skills, and critical awareness (i.e. attitudes and values) to act and contribute accordingly. This requires research, education, and suitable institutional conditions that enable people to focus on SD. We consider SD a continuous global and societal process of searching, learning, and shaping. International collaboration has led to the globally agreed UN 2030 Agenda. This is promising. But even though the SDGs are set, implementing them still requires a negotiation of trade-offs at all levels.

The obvious question, then, is what can we do? We have three options:

• We let evolution run its course: We take a business-as-usual approach, ignoring indicators of unsustainable development. Eventually, we find ourselves in a dead-end road with no way of turning or reversing – and with disastrous consequences for the entire planet.

• We reform the system: We envisage sectoral changes, e.g. in managing natural resources, optimizing fuel consumption, insulating houses, avoiding food waste, etc., without questioning the prevailing global

“system”. “System” here refers to the current, global, economic utilization of natural resources by society.

It is unclear, however, whether changes within the system are enough to save the planet or whether they remain merely cosmetic.

• We transform the system: If reforms within the current system are considered insufficient, there is a need to discuss a transformation, a specific type of social and institutional change within and of the system, which is knowledge- and evidence-based rather than opinion- and ideology-based.

While these options are currently under debate, numerous scientists (e.g. WBGU 2011) suggest a “Great Transformation”. We should also bear in mind that the subheading of the UN 2030 Agenda and the SDGs is “transforming” our world, not reforming it!

According to the UN understanding, the main goals of SD are socio-economic equity and justice while using natural resources respectfully. SD is a process of searching, learning, and shaping, and requires the participation of all actors. Their knowledge and empowerment should be based on research and education.

1.3 Sustainability Science: Transdisciplinary Research for Sustainable Development

Aspects of global unsustainable development, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, poverty, etc. are often identified or verified by research. What do scientists do with these findings? Do they leave policymakers and other actors to interpret research results and draw their own conclusions, or should science assume more responsibility, for instance, by devoting certain activities to help mitigate complex global problem settings? The following argues what type of science and research supports SD, and further, what type of education supports sustainability science. This is not a literature review. Instead, as the title of this book suggests – we are sharing our experience in course and curriculum design. We therefore focus on two main approaches that we have applied and that reflect our long-term experience: transdisciplinary research and transformative learning.

Scientific research options may be “disciplinary” (involving a single discipline), “interdisciplinary” (in cooperation with other disciplines), or “transdisciplinary” (different disciplines working with the participation of various stakeholders from practice).

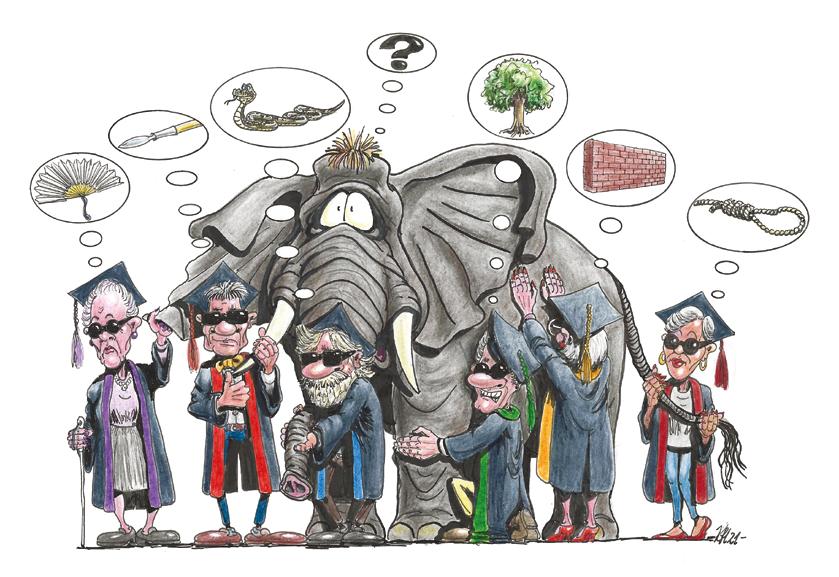

Cartoon 3: Disciplinary science and complex realities (Illustration: K Herweg)