4 minute read

Figure 5: Steps of integrating sustainable development into tertiary education

from Transdisciplinary Learning for Sustainable Development: Experience in Course and Curriculum Design

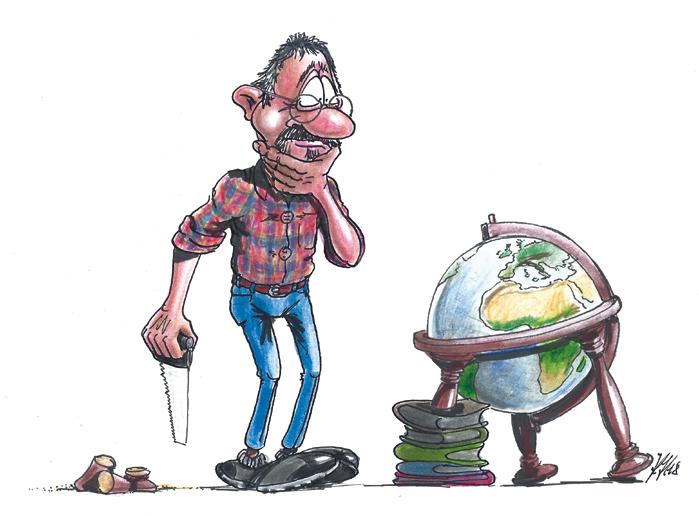

Cartoon 5: Disciplinary Academic Structures: the world has problems; the university has faculties (Illustration: K. Herweg)

Despite this institutional barrier, there are a number of possibilities for integrating SD into curricula and courses (Figure 5; after Sterling and Thomas 2006). Newcomers to SD might consider, in a first step, applying a “Bolt-on” approach. This means that in individual lessons or sessions, they could include a discussion about what potential links their discipline has to SD, and, as a result, what contributions it might make. In a next step of engagement, a “Build-in” approach – creating an entire course around SD – is an opportunity for more in-depth discussions and exercises related to SD. To make full use of the potential of higher education for engaging in SD would require a “Curriculum redesign” or the creation of specific SD study programmes, supplemented by further education modules.

Curriculum redesign – sustainable education • Students are able to make relevant contributions to interdisciplinary teams in cooperation with practitioners. • Lecturers are able to integrate SD in their disciplinary courses and build up SD-related competences.

Further education, workshops

SD-related curricula / study programmes

‘Build-in’ approaches – education for sustainability • Students are able to analyse a complex problem context and elaborate different solution scenarios.

‘Bolt-on’ approaches – education about sustainability • Students can describe links between their own discipline and SD. SD-related courses

SD-related lessons / sessions

Figure 5: Steps of integrating sustainable development into tertiary education (K. Herweg, after Sterling and Thomas, 2006)

A “Curriculum redesign” requires ownership, engagement, and support of the institution. But even if the institution neither engages in ESD nor supports SD curricula, you can still transform your own courses through “Bolt-on” and “Build-in” approaches. Below, we further explain our focus on teaching and learning that supports students and lecturers in engaging with transdisciplinary research.

You have many options for integrating SD into your teaching, both at the institutional and at the coursework level.

ESD can prepare people to assume more responsibility and take a much more active role in transforming society towards SD: this is implied when considering SD as a continuous global societal process of searching, learning, and shaping. We began by thinking how to improve the role of science, i.e. research and education, in SD. In Chapter 1.3 we discussed td research – which can also be conceptualized as knowledge co-production and social learning – as highly suitable options for sustainability science. But social and individual learning processes go hand in hand. Transforming our individual ways of thinking and contributions to unsustainable development will thus be our starting point.

I’ve cut it three times already, and it’s still too short …

Cartoon 6: A “Great Transformation” … is NOT about doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results (Illustration: K. Herweg)

In this context, the debate in ESD literature about “transformative learning” (TL) is highly relevant. TL is a process by which we transform our problematic and taken-for-granted mind-sets, paradigms, frames of reference, behaviours, and habits (Mezirow 2000). Mezirow described the basic premise of human thought, feeling, and action as “meaning perspectives” or “orientation-giving templates” for perceiving and interpreting new experiences. In a way, these meaning perspectives function like a pair of glasses that deny us an objective perception. Our values and sense of self are anchored in our frames of reference. They provide us with a sense of stability, coherence, community, and identity. Consequently, they are often emotionally charged and strongly defended. Viewpoints that call our frames of reference into question may be dismissed as distorting, deceptive, ill-intentioned, or crazy. Therefore, they are particularly difficult to change.

Mezirow’s focus on the individual was supplemented by Brookfield (2000), who compares transformative learning to a “shift in the tectonic plates of one’s assumptive clusters” (ibid. 139), but strengthens the importance of critical reflection as a collaborative project and a social process. A community of peers can serve as critical mirrors and provide emotional support on transformative learning journeys. O’Sullivan (2002) further stressed the societal level by stating that we are living in a period of earth’s history that itself is undergoing a transformation. All educational ventures must therefore be directed towards responsibility for the planet. Both individual and social learning for transformation demands leaving one’s personal comfort zone, which involves a certain level of disruption of our current ways of thinking and doing.

ESD has embraced TL as an approach to support learning that leads to transforming mindsets towards sustainability. A systematic literature review by Rodríguez Aboytes and Barth (2020) shows that from 1999 to 2007, the TL theory played a minor role in sustainability learning and ESD research. From 2008 to 2019,