8 minute read

Sunday Reflections

‘And with the morn those angel faces smile, which I have loved long-since and lost awhile’ These words from a poem of John Henry Newman, which eventually came to be set to music and which we sing as the hymn ‘Lead, Kindly Light’, seem particularly well suited to the month of November. This, after all, is the month when, in our Catholic tradition, we pray in a particular way for the faithful departed, the angel faces which we have loved long since and lost – but only for a while because they have gone before us marked with the sign of Faith, the sign of the Lord’s Cross.

Newman’s words speak not only of the beloved dead but also of the desire for a true homecoming for us all – the coming home to the Father’s House, where there are indeed many rooms and where a place is prepared for us all (John, Chapter 14, Verses 1-6). In his poem, Newman sees that the gloom and the difficulties of this life (the ‘crag and torrent’) are overcome and vanquished by the vision and hope of peace eternal. He also acknowledges that God’s providence and care has always been with him – and therefore he can have no doubt but that God will continue to be faithful: ‘So long thy power hath blessed me, sure it still will lead me on.’ The Liturgy remembers our deceased brothers and sisters every day, not just on the Commemoration of All Souls (2 November) or indeed in the month of November. It is a wholesome custom to compile our November Lists (sometimes referred to as the Pious Lists) – those people for whom we pray daily in the month and for whom Masses are offered - but in the Eucharist each day the Church remembers those who have died and prays that, by the tender mercy of the heart of our God, they will share in the joys of the Blessed. And so we pray with the Liturgy of the Church: Remember also, Lord, your servants (here names may be added) who have gone before us with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace. Grant them, O Lord, we pray, and all who sleep in Christ, a place of refreshment, light and peace.

Advertisement

Sunday thoughts Mgr John Devine OBE

A few weeks ago I visited Stratford for the first time in over 50 years. I came as a pilgrim, one of many thronging the streets from all parts of the world. It felt like Lourdes. The cafés were full. There were shops filled with Shakespeare memorabilia. Some was cheaply produced tat. I enjoyed a performance of Richard III at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. The audience almost perfectly matched the age profile of those who attend Mass. (Lourdes, on the other hand, has a special appeal for our young people, drawn by the desire to support sick pilgrims.) There were also books on sale – multiple editions of the Bard’s plays and sonnets and books of commentary for students. There were framed quotations from Shakespeare’s work and T-shirts in abundance. I was reminded of an article by Bernard Levin on how the words of Shakespeare are imbedded in everyday language. He wrote: ‘If you cannot understand my argument and declare “it’s Greek to me”, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you claim to be more sinned against than sinning, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you recall your salad days, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you act more in sorrow than in anger, if your wish is the father of thought, if your lost property has vanished into thin air, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you have ever refused to budge an inch, or suffered from green-eyed jealousy, if you have played fast and loose, if you have been tongue-tied, a tower of strength, hoodwinked or in a pickle, if you have knotted your brows, made a virtue of necessity, insisted on fair play, slept not one wink, stood on ceremony, danced attendance (on your lord and master), laughed yourself into stitches, had short shrift, cold comfort or too much of a good thing, if you have seen better days or lived in a fool’s paradise – why, be that as it may, the more fool you, for it is a foregone conclusion that you are (as good luck would have it) quoting Shakespeare.’ Some of Shakespeare’s words would not be out of place on the lips of Jesus in the Gospels. One quotation on display struck me. It’s a mother’s advice to her young son as he leaves home to serve at court: ‘Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none’ (All’s Well That Ends Well, Act 1, Scene 1).

What can separate us from the love of God

Some months ago, a friend who has mental-health issues invited me to a concert at the Philharmonic Hall. It was hosted by an organisation called Life Rooms which provides a safe place for people to gather and do various courses to enhance their mental health.

My friend was taking part in this concert and wanted her mother, me and a few friends to go along. I was not prepared for the emotional rollercoaster that happened within me as I listened to these extraordinary people share deep reflections, not only about their issues, but also about their giftedness.

The second half of the concert left me an emotional wreck. Each of the participants shared why a particular song had had an impact on them. My friend used the song ‘Another Day in Paradise’. She told how she had wandered through life thinking everybody else was living in paradise and that she would never experience it. My heart broke as I listened to her talk about the amazing turnaround in her life; she now knows that she tastes paradise because of the drugs that control her mentalhealth issues and through the love of a God who had never left her. She knows that whatever has happened in her life – breakdown, depression, voices in her head, hospitalisation, suicide attempts – nothing can separate her from the love of God.

Psychologists tell us that deep within, all of us are either guilt-based or shame-based people; we carry the guilt of not being good enough. We have a deep sense of shame about who we are. Some of us live life hating ourselves and rejecting those things within us that we see as weak or immoral or bad. The problem is that we will not believe who we are: God’s beloved children. I think most of the journey in faith is about discovering who we truly are. We have to discover that God really does love us, that we are children of God despite what has happened in our lives. That is our true identity. Guilt and shame will not help us know that. Only Jesus can do that. Thank God that is what Jesus has done. It is when we realise that we are God’s beloved son or daughter that life takes on a new meaning, and we know that God will never abandon us, and that love is all around us and within us. Nothing can separate us from the love of God.

from the archives Remembering civilian deaths in war

by Neil Sayer, Archdiocesan Archivist

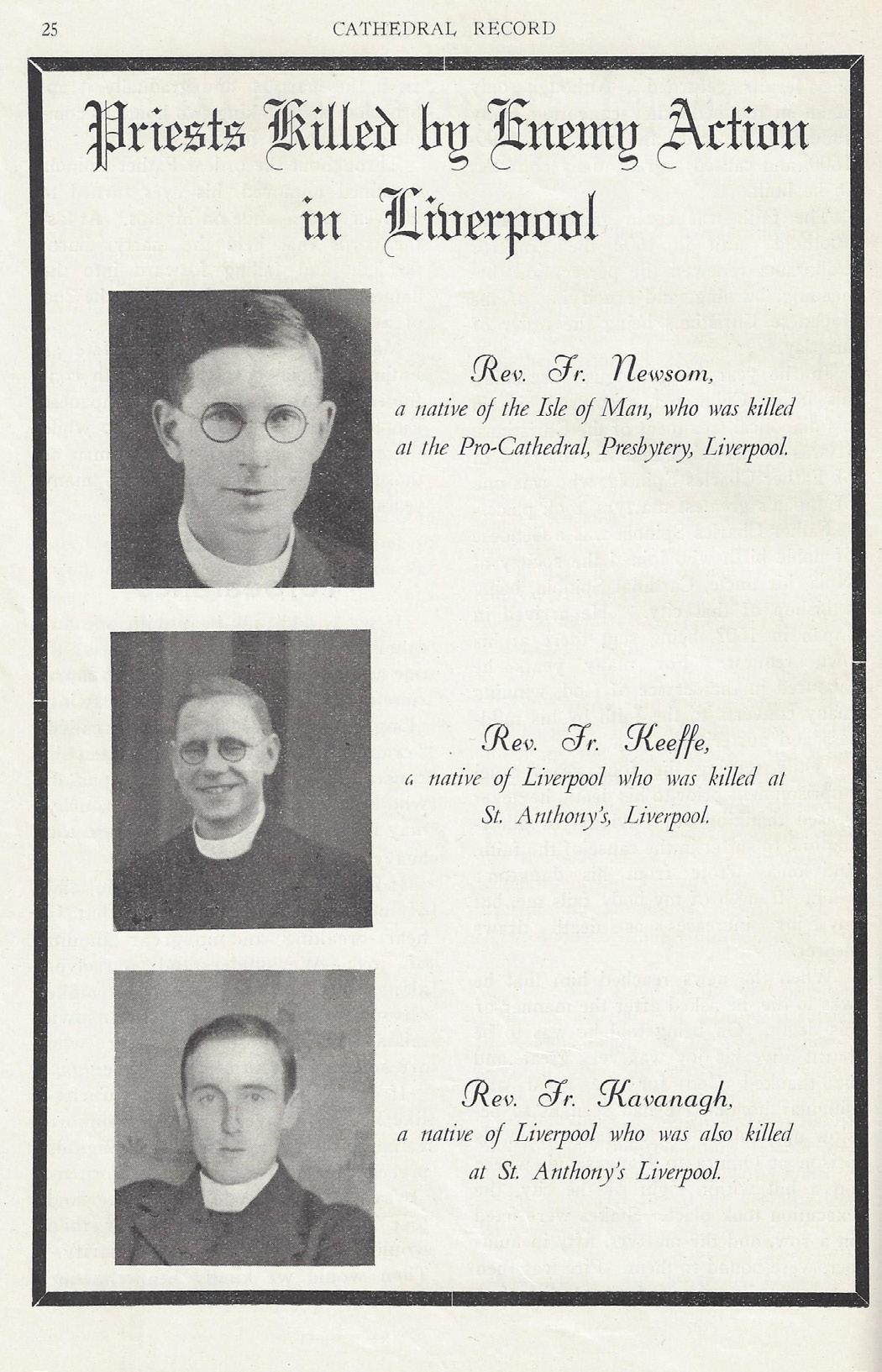

Father Newsom and Father Keeffe were classmates at both St Edward’s College and at the Seminary at Upholland. They were killed in air raids within months of each other in 1940. This November might be a time to remember them and all other civilian deaths in wartime.

Percy Newsom was born on the Isle of Man in 1906 and crossed the Irish Sea in 1919 to continue his studies at St Edward’s College in Liverpool. Following his ordination in 1932 he became assistant priest at Sacred Heart in the city. He then served at the Pro-Cathedral of St Nicholas but had been there for barely a month when the presbytery received a direct hit from a German bomb during the night of 21/22 September. Father Newsom was killed, his colleague as curate, Father Martin Lydon, was seriously injured, and the Pro-Cathedral Dean, Canon James O’Connell, miraculously escaped uninjured. Chance played a great part in surviving the bombs. Father Joseph Wareing recalled the time St Sebastian’s was hit when he was Parish Priest there, ‘On the evening of the 17th September 1940 very shortly after the conclusion of the Quarant’Ore an enemy plane in the course of two runs dropped in all seven bombs between the front of the church and the front of the Presbytery. One of these scored a direct hit on the Church falling immediately in front of the Sanctuary – tearing up one third of the floor – splitting the Chancel Arch – completely demolishing the altar rails and font pit. When this bomb fell the church had just been cleared of some twelve people who had remained after the Service to say the rosary and who were actually in church when the first bombs fell outside. No one was hurt.’

As the Luftwaffe turned towards night bombing raids following defeat in the Battle of Britain, the death toll of civilians mounted. Liverpool endured a number of attacks just before Christmas 1940. In one of these, on 21/22 December, Father Wilfrid Keeffe lost his life. He had started at St Edward’s College on the same day as Percy Newsom, they had transferred to Upholland together, and both were ordained on the same day. Father Keeffe had been at St Anthony’s on Scotland Road since then. Killed in the same raid were Father William Kavanagh and nine others, including Mr and Mrs Thompson and their three young children, all of them in the air raid shelter of the parish school when it received a direct hit. Archbishop Downey acknowledged the strain his priests and their flock were under: in his Lenten Pastoral Letter issued in February 1941, he commended the devotion to duty and spirit of self-sacrifice exhibited by ‘priests and many others’. ‘Some’, he said, ‘have seen their churches, schools and presbyteries wrecked and themselves rendered homeless; others bemoan the ruthless slaughter of faithful parishioners, including women and children.’ The heaviest toll of civilian casualties in Merseyside was yet to come. In the May blitz of 1941 parts of the city centre were completely destroyed and, across Liverpool and Bootle, damage to housing made around 70,000 people homeless. Six churches, five presbyteries and four Catholic schools were completely destroyed. In just a week, 1900 people were killed. Mass burials took place in Anfield Cemetery. Our remembrance services should include those not in uniform.