25 minute read

History of the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Club

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe was clearly a remarkable and independent woman, deeply concerned about a wide range of social issues, and with a profound interest in art. That the Club founded to honor her memory has survived for over 125 years is a tribute to the many women, also strong and independent and with widely diverse talents, who have been inspired by the standard she set and who have stepped up to the new challenges of constantly changing times. The fact remains that although opportunities for and recognition of women artists have increased, there is still a need for organizations fostering the position of women in the arts. The Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Club has evolved in many stages, from a comfortable and welcoming home for young women in New York, struggling to gain recognition in all areas of arts and crafts, to a group of highly professional artists drawn from all regions of the country.

Although in the early days the Club was perceived as a social support for needy and lonely students, the members’ serious commitment to art was evident in the continually renewed exhibitions they mounted in their rooms at Grace Church. Underlying the sense of mutual support and camaraderie was always the desire to demonstrate genuine professional achievement. As Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, the noted sculptor, stated in her letter of thanks for having been honored at CLWAC’s 75th Annual Exhibition in 1971:

Advertisement

This combination of genuine support for fellow artists and dedication to serious artistic values has been crucial to keeping CLWAC alive.

Our Club has always kept its standards high and never dipped its colors in the direction of eccentricity and caprice in art.... Don’t think for an instant that I mean to suggest that art should be static. Art is life and ebbs and flows, is depressed and exultant–but if the artist is to help his fellow man– to lift his spirit...he must portray truth and beauty, and in doing so there is no substitute for style and mastery of technique.

Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, 1880-1980

The American Cathedral in Paris

Dr. William Reed Huntington, Rector of Grace Church, 1838-1909

The 1880s and 1890s were a time when many social and artistic movements emerged. In the arts women had been struggling for decades to gain access to serious training and to establish the concept that being independent and strong-minded need not connote being disreputable. Many had gone abroad to France and Italy to study, and in the 1890s several women’s arts groups were organized in New York, the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Club being one of the first.

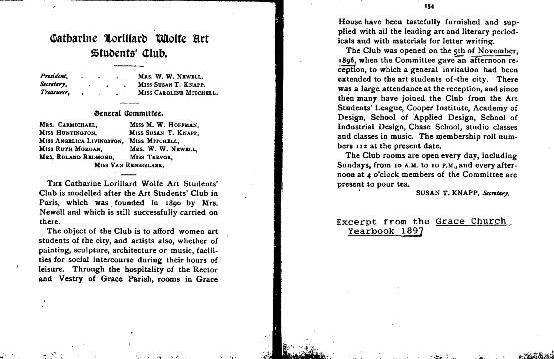

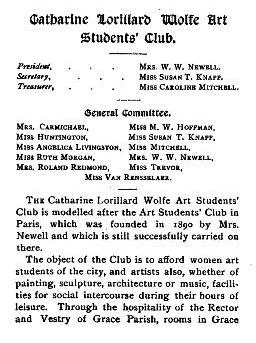

As has been noted, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe was in her lifetime a very generous benefactor of Grace Church, and at her death in 1887 bequeathed a substantial endowment to the Church for “some form of women’s work.” It happened that the wife of the rector of the Episcopal church in Paris, Mrs. W. W. Newell, had formed a very successful club there to aid young American women art students. After the death of her husband, she returned to New York, and the rector of Grace Church, Dr. William Reed Huntington, invited her to create a similar club at the Church, using the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe bequest and honoring the person who herself had demonstrated an enduring commitment to art. The Parish House at Grace Church, Grace House, had already been built with funds provided by Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, and the Church made available to Mrs. Newell some rooms on the second floor to serve as space for the Club. Although the funds and the facilities came from the Church, both Dr. Huntington and Mrs. Newell made clear from the beginning that the Club was to be non-sectarian and open to all. The purpose was to offer a warm and supportive meeting place for young women attempting to find their independent way, often without financial or social resources.

The Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Students’ Club was initiated at a reception in November 1896, a general invitation having been sent to women art students in the city, at the Art Students League, Cooper Union, the National Academy, and other institutions. The response was large and enthusiastic. The definition of art was broad, including musicians, writers, potters, and other crafts students, as well as painters and sculptors. This was at the height of the Arts and Crafts movement, when there was a strong push to establish crafts as a serious part of the art world. Cooper Union had a well developed crafts program, and its proximity to Grace Church brought many students to CLWAC. Many other early members came from the Art Students League, and in a short time participants numbered more than 150.

“Life Class,” published in the New York Times, 1896

Excerpt from the Grace Church Yearbook, 1897

The rooms at Grace House were open every day, presided over by the women of the Church. The teas and monthly Sunday night suppers doubtless provided some much needed sustenance to many of the students. But the meeting place offered much more than that. The rooms were supplied with art books and magazines, in addition to the Grace Church Library to which the students were given free access. Most importantly, proper lighting was installed so that the rooms could serve as galleries for the exhibition of the students’ work. A full range of art and crafts was regularly shown and rotated on a monthly basis. And because a substantial number of musicians, writers, and drama students belonged to the group, frequent musical and dramatic performances were presented. One of the strong impressions gained from the many reports in the Grace Church Yearbook about the activities of CLWAC is a sense of high spirits and adventurous undertakings. It was a stimulating place for the exchange of ideas, as well as a comfortable and reassuring retreat.

While the gallery space at Grace House always had the students’ work on view, an annual exhibition and reception were primary features of the Club’s activities from the beginning. In the first few years they were held at Grace House, but in 1909 the New York School of Art offered its gallery for the yearly exhibit, beginning the expansion of the Club to wider recognition and toward more professional status. In 1917 the name of the Club was changed to the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Club, eliminating the reference to students, since many of the members were in fact teachers and professional artists. Clearly women artists were gaining acceptance.

The activities of CLWAC remained consistent for the next few years, with the members of the Church still presiding over the afternoon tea hours and the management of the Club. But in 1925, when the membership had grown to include many more professional artists, and when the funds left by Catharine Lorillard Wolfe had been exhausted, the Club reorganized. Members and their exhibition oportunities were restricted to women artists residing in the greater New York area, and the responsibilities of running the Club were taken over by its members. However, the Church very generously continued to provide the same space and opportunities for monthly exhibitions and the concerts and musicales that had been so much a part of CLWAC. Annual Members’ exhibitions were held in the Academy room at The American Fine Arts Building, 215 West 57th Street, an arrangement that continued into the 1940s, when the Club began to have annual exhibitions in the Wanamaker store across the street from Grace Church. Some shows continued to be mounted at the Church but were discontinued as the membership grew in numbers and standing.

Originally The American Fine Arts Building, today home of the Art Students League

A door knob from the days of the AFA still exists

Photos courtesy of the Art Students League

Lever House, site of Members’ Exhibitions until 1992

The National Arts Club, Gramercy Park South, New York City. Site of the first Annual Open Exhibition, 1954

Program for a Members’ Exhibition at the LaGuardia Airport main terminal

In 1954 the Club, under the leadership of Florence Fitch Whitehill, was reorganized once again by extending membership to all professional women artists, regardless of residence, although it was stipulated that they adhere to traditional values in art. The first Open Exhibition was held in March of that year at the National Arts Club, housed in the historic landmark Tilden mansion. Built in the 1840s, the mansion was acquired in the 1860s by Samuel Tilden who undertook extensive improvements, hiring Calvert Vaux for the facade, John LaFarge for stained glass ceilings, and Italian woodcarvers for parts of the interior. Its galleries provide a prestigious venue for the exhibition of many art organizations, but the fact that the National Arts Club admitted women to membership from its inception in 1898 made it particularly fitting for the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Art Club to exhibit there. The first Open Exhibition was a tremendous success, with 281 works on view. The entries must have seriously strained the capacities of the NAC galleries, with 177 oils, 76 watercolors and pastels, and 28 sculptures. The number of sculptures exceeded expectations. While there had been sculptor members for years, the Open evidently attracted new attention. Anna Hyatt Huntington, Elisabeth Gordon Chandler, Katharine Thayer Hobson and Brenda Putnam, all National Academicians, were among the exhibitors. Non-member entries came from as far afield as Texas, Idaho, and Canada.

This first Open Exhibition was followed the next month by a Members’ Show at the Eighth Street Gallery, one of many there. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the Club mounted numerous Members’ exhibitions at many varied locations: the Gramercy Theater, the Butler Gallery, Burr Galleries, Lever House, the Architectural League of New York, The Greater New York Savings Bank, the Seaman’s Bank for Savings, even LaGuardia Airport. Most of these venues offered space without fees; one of them, Churchill’s Gallery at 139 Broadway, stated that its concept was to “Present Gallery Space to Deserving Artists Without Any Expense to the Artist.” These locations enabled CLWAC to provide its members many opportunities to exhibit their work at minimal cost. All that was required was a great deal of energy, and this the Club indeed had. The publication of a monthly newsletter, Highlights, was also undertaken at this time by a most exuberant Verall Wright. While the Club no longer exhibited at the Church or presented programs there, some of the party spirit remained. At a New Year’s party in 1955 the daughter of one of the members gave a song recital, accompanied by Sara Boal on the piano, presumably the Steinway purchased for the Club early in the century.

Florence Fitch Whitehill, 1903-1984

Anna Hyatt Huntington, 1876-1973

Elizabeth Gordon Chandler, 1913-2006

Awards Created for CLWAC

Medal of Honor Medallion created by Victor David Brenner (1871-1924)

This is the Club’s highest award given at the Annual Open Exhibition since 1962. It is awarded in four categories, provided there are at least 25 artworks in each: oil/acrylic, watermedia, pastel/graphic/mixed media and sculpture. The allegorical figure of a classically attired standing woman holds a palette, a mahlstick, and a winged statuette, symbolizing painting, sculpture, and by extension all the visual arts. The sculptor, Victor David Brenner, was born in 1871 in Shavli, Russia and came to the United States in 1890. Among his innumerable works is a long list of medals and plaques including: The Municipal Art Society Award Medal, The American Institute of Architects Seal Medal, The Boston Surgical Society, The Peace Plaque, and two bronze plaques of Lincoln and Washington situated in the lobby of the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania City-County Building. Brenner was also the designer of the Lincoln cent issued in 1909.

Anna Hyatt Huntington Bronze Medal created by Sally Swan Carr

This award, given in the same categories as the Medal of Honor, was created in 1970 by then CLWAC Vice President Sally Swan Carr in recognition of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s outstanding career and her generosity and dedication to CLWAC. The award was established with funds donated by Huntington herself and continues to honor her each year. Sally Swan Carr, who served as CLWAC’s President from 1971 to 1974, was herself a distinguished sculptor. Working in stone, wood, and bronze, she had many commissioned works in the United States and Europe. The Anna Hyatt Huntinton Medal is also in the Numismatic Society in New York.

Creative Hands Award created by Lucille C. Hampton

This small, gold-covered bronze sculpture is awarded each year to one of CLWAC’s Members or supporters who has selflessly contributed to making possible the work of the Club and its exhibitions. Lucille C. Hampton, a long-time Member of CLWAC, is a sculptor of distinction, represented in prestigious galleries and with many commissions. Her years of contact with both collectors and patrons of the arts led her to appreciate the contributions made by those who work behind the scene, above and beyond the call of duty. In 1984 she sculpted this award, inspired by Michelangelo’s “Creation,” to recognize those who help bring life to creative work. Lucille was our Honored Member in 1994.

Horse’s Head Award created by Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973)

This award is given annually at the CLWAC Members’ Exhibition for the best sculpture and twodimensional works. Anna Hyatt Huntington created it in 1966 expressly to be awarded at the Members’ Exhibitions, and it is representative of the innumerable ways in which this most distinguished sculptor, one of America’s most outstanding, contributed to CLWAC in both creative and practical ways over many years. She was an Honorary Member, and in appreciation, CLWAC also named her an Honored Member in 1969, 1972, and 1973.

Artist Laureate Award created by Board Member Emeritus Jeanette Koumjian

To coincide with the Club’s 125th Anniversary and each year going forward, this enameled medallion will honor those who, over an extended period, have been dedicated to the eloquent expression of their creative vision, encouraged innovation, strengthened the broader art community through service, shared their experience with peers and, through their generosity of spirit, commitment, perseverance and grace, enhanced the future for all women artists.

In 1965 President Margaret Fernald Dole enlisted her able lawyer husband John Dole to help the Club take the important step of incorporation. In 1966 President Sara Metzner Boal, again through the efforts of John Dole, obtained the crucial 501(c)3 taxexempt status that has made the survival of CLWAC possible. She also initiated the relationship with The Metropolitan Museum of Art that led to annual exhibitions’ opening receptions serving as benefits for the Museum. The funds raised have been used by The Metropolitan to establish a small endowment assisting curators in the American Wing to travel to many venues germane to their work. The Museum has graciously enhanced this association by providing speakers from its staff each year at CLWAC’s Benefit Reception and Awards Dinner, giving insight into the ways modest contributions from the Club perpetuate the true legacy of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe by sponsoring unfettered interest in art. One of the early speakers, at the Benefit Reception in 1969, was the future Director, Philippe de Montebello, at the time Associate Curator in the Department of European Paintings.

During the 1960s Sally Swan Carr, who later became President, was very active in persuading the prominent sculptors Anna Hyatt Huntington, Harriet Frishmuth, and Malvina Hoffman to become Honorary Members of CLWAC. Anna Hyatt Huntington became strongly supportive and made available to CLWAC casts for a number of her small sculptures that could be sold or auctioned as “Museum Pieces” at both Annual Open and Members’ Exhibitions. The proceeds would then be dedicated to funds for awards. She also created the Horse’s Head Award specifically to be awarded at the Club’s annual Members’ Show. During this period several members of CLWAC visited Huntington at her home and studio in Connecticut. Sally Swan Carr, after seeing Huntington at work on the maquette for her “General Putnam” statue, was inspired to create the Anna Hyatt Huntington Bronze Medal to be awarded at Annual Open Exhibitions. Huntington was honored in 1966 at the 69th Annual, at the time of her 90th birthday, where a number of her works were shown, and the catalog was dedicated to her. Other Honorary Members were also given special recognition. Harriet Frishmuth was particularly honored at the Members’ Exhibition at Lever House in 1966, and the Members’ Show in November 1966 in the New York Bank for Savings was dedicated to the memory of Malvina Hoffman. The 76th Annual Open Exhibition, at the National Arts Club in 1972, recognized all the Honorary Members: Florence Julia Bach, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, Harriet Frishmuth, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Brenda Putnam, Priscilla Roberts, and Katharine Weems.

Margaret Fernald Dole, 1896-1970

John Dole

1969 Benefit Reception for The Metropolitan Museum of Art Left, Philippe de Montebello Associate Curator of the Department of European Painting Right, Sally Swan Carr

National Academy of Design Museum

Photo by David Plakke Media, 2011

Charles W. Hawthorne

Frank Vincent DuMond

Starting in 1967 under Sara Metzner Boal, the annual exhibitions were held at the National Academy of Design, where they continued through 1971. It is interesting that the National Academy building was designed as his home by Anna Hyatt Huntington’s father-in-law and was occupied by Anna and Archer Huntington until 1940, when Archer deeded it to the National Academy. For a number of years the Academy provided space for several arts groups: Allied Artists of America, Audubon Artists, the American Watercolor Society, and the National Association of Women Artists, to hold their exhibitions. It later changed its policy, and CLWAC returned to the National Arts Club, where exhibited for more than 60 years.

CLWAC’s last exhibition at the National Academy of Design, its 75th Annual Open Exhibition in December 1971, was a large and gala event. While CLWAC continued to emphasize traditional values, so eloquently enunciated by Harriet Frishmuth in her letter to the Club upon receiving the Gold Medal of Honor at the 75th Annual, the work always met the highest standards of quality and creativity. A review of the 75th by Lillian Wachtel in the Gramercy Herald of December 10, 1971, stated:

Sara Metzner Boal, 1896-1979

I wish I could do justice to all the fine work in this vast and varied exhibition which shows how alive and human and contemporary the “representational style” can be.

A separate 75th Anniversary Catalog was produced in honor of this milestone, with biographies and photographs of work by many members. The Club was able to take advantage of the three floors of exhibition space at the National Academy to mount an extensive show and bring in such prominent jurors as Donald Greene, Everett Raymond Kinstler, Vincent Glinsky, and John Terken. CLWAC called on distinguished awards jurors from outside the Club well before many other groups did (as early as 1930 it had Charles W. Hawthorne, Frank Vincent DuMond, and Gustav Wiegland as jurors) and was not shy about having outstanding men as well as women judge their work. This fact probably contributed much to CLWAC’s reputation for presenting work of exceptional quality. The Club was also pleased to honor some of the men who had been particularly helpful to it. In 1974 it dedicated the Annual Catalog to three Honorary Patrons, John Dole, A. Hyatt Mayor (Anna Hyatt Huntington’s nephew and a curator of prints at The Metropolitan Museum of Art), and Max Gelfound, a most helpful accountant.

A. Hyatt Mayor, nephew of Anna Hyatt Huntington and Honorary Patron of CLWAC

1976 Members’ Exhibition at The Greater New York Savings Bank

Manufacturers Hanover Bank, 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue Members’ Exhibitions venue

The years following the 75th anniversary were filled with activities. The Club held regular general meetings for which energetic program chairmen engaged outside speakers, many provided through the generous interest of Robert Friedman, Coordinator for The Metropolitan Museum’s Community Program, who also arranged for a special tour of the museum. Other speakers, such as the well-known watercolorist Mario Cooper, Michael Lanz of the National Sculpture Society, and James Cox of Grand Central Galleries, were willing to contribute their time and expertise to give informative presentations. Cox even invited CLWAC to have as one of its meetings a tour of his new gallery space. For a number of years it was possible to find free or inexpensive space for Members’ Shows at such places as Manufacturers Hanover Bank, the Union Carbide Building, Lever House, or the Customs House at the World Trade Center, and successful exhibitions were regularly mounted. In time, however, it became more difficult to locate feasible venues, and in the 1980s there were some years in which Members’ Shows could not be managed. As members’ lives became more challenging it was also more difficult to present frequent general meeting programs. Notes in the Highlights newsletter of members’ activities reveal the remarkable extent to which CLWAC artists were successfully pursuing exhibition opportunities all over the country. Increasingly the membership became national in scope, and even those in the New York area were moving outside the city to live and work. This made it harder to organize and have sufficient attendance at events, although the supportive spirit of the Club remained high.

At the same time, the number of members increased, while the standards for becoming a member were raised. In 1978 under the leadership of President Carey Boone Nelson the Bylaws were amended to require that artists would become eligible to apply for membership only after they had been juried into three Open Exhibitions with the added stipulation that they submit images of a substantial body of work for evaluatiion. As the requirements for Artist Membership became stricter, a category of Associate was initiated in 1978, exempting those interested in participating in many activities of the Club (barring voting rights and eligibility for Members’ Shows) from the necessity of meeting the full Artist Member prerequisites.

The Union Carbide Building, Park Avenue Members’ Exhibitions venue

Photo from The Midtown Book by Carter B. Horsley

Carey Boone Nelson

By 1979 the number of entries had grown to the extent that it became necessary to require Members to be juried every other year for the Open Annual in order to make space to hang the increasingly high-quality work being submitted.

As CLWAC moved towards its 90th anniversary it had successful Members’ Shows at the Customs House, Lever House, and the Salmagundi Club. The Annual Open Exhibitions at the National Arts Club attracted an ever larger number of artists from across the country, and the Opening Receptions to benefit The Metropolitan Museum were supported by the President of the Museum, William Macomber. At the festive Preview for the 90th, the new President of The Metropolitan Museum, William Luers and his wife Wendy received an enthusiastic response after they both spoke. To help celebrate its 90th the Club published another Anniversary Catalog, similar to the 75th, devoted to biographies of many members and photographs of their work. The Club continued to draw on prestigious representatives of the art world for its jurors of awards: Harvey Dinnerstein, George Hollerbach, Paul Wood, Moses Worthman, Fritz Cleary, Edward Hoffman, Nat Kaz, and Albert Wein, to name a few, along with Everett Raymond Kinstler, who served many times.

But the 1980s were also a period that required serious adjustments to deal with changing times. President Nora Roth undertook the task of assuring that the Club continued on a sound financial basis, as the costs of everything went up and volunteers were more and more pressed for time. A major achievement under her leadership was the creation of a sizeable medals fund. Through a concerted effort, and with the help of Patron Albert Ehinger, she was able to raise a substantial sum that has carried the Club through all the following years. Her gentle insistence that things be done in a businesslike manner helped channel CLWAC in a productive direction. At the same time there was growing recognition that the Club needed to be receptive to a wider range of art. While continuing to stress that traditional values were of primary importance, there was a move to encourage entries in somewhat more contemporary styles and to accept Artist Members working in more abstract modes. The strict requirement of representational art was deleted from the prospectus.

As CLWAC approached its 100-year anniversary, the vivacious and enthusiastic President Karen Strong began exploring various plans to celebrate the event. Eventually the Board determined that one of the best ways to demonstrate the continued vitality of the Club would

Judging the1989 Annual Open Martin Kalish and Harvey Dinnerstein

Mr. and Mrs. William Luers, President of The Metropolitan Museum of Art with CLWAC President Nora Roth

Jean Kroeber and Amy Unfried

Members’ Exhibition 1996

The Broome Street Gallery, New York City

The Salmagundi Club, located at 47 Fifth Avenue at 12th Street, New York City, is the oldest professional art club in the United States Left to right: Building entrance, Parlor and Upper Gallery

be to mount a traveling exhibition, something CLWAC had never undertaken. Karen enlisted Dorothy Barberis, former Membership Chair and Painting Chair, to locate galleries and exhibition spaces and introduce curators to the Members’ work. Dorothy devoted many months to the task and set up rigorous standards for Member participation. Painters were to submit three works and sculptors two, all of which were to be juried by outside judges who determined which artists qualified and which single piece of their work would be in the show. The jurors, Paul Wood, Karl Molno, and Roger Cosgrove in the Fall of 1995 selected 62 works, and in January 1996 the exhibition opened at the Broome Street Gallery in SoHo. Karen Strong produced the fine catalog, with photographs of all the works, and new President, Jean Kroeber, undertook the further organization of the show, firming up venues and finding new ones when that proved to be necessary.

The exhibition traveled to ten more locations over the next two years, from the Philip and Muriel Berman Museum at Ursinus College in Collegeville, PA (the first time the Museum devoted an entire exhibition to women artists), to The Midwest Museum of American History in Elkhart, IN, to its final installation at Hartwick College, in Oneonta, NY, ending in January 1998. The venues were all enthusiastic about the exhibition and provided expert care in handling the artwork, each gallery taking responsibility for shipping the collection to its next location. Lindsay Hooper of the Shenandoah Valley Art Center in Waynesboro, VA, (the third stop on the tour) commented: “This is an amazing show, a beautiful show. It rivals any collection I’ve seen.” Michelle L. Smith, Director of the Wassenberg Art Center in Van Wert, OH, commented: “This is a GREAT show! The work is highly professional.” At the end of the tour the works were all safely returned to the participating artists, with only one pastel suffering slight damage, a remarkable tribute to the respect and care with which all the venues treated the artists’ work.

The opening installation of the Centennial Traveling Exhibition at the Broome Street Gallery, headquarters of New York Artists Equity, was the beginning of a long association with that organization. New York Artists Equity is a strong advocacy group for artists, and its gallery provided an excellent venue for CLWAC’s Members’ Shows for a number of years in an environment quite different from the National Arts Club. These shows extend to CLWAC Members opportunities to exhibit work, not limited by size, nor juried for acceptance, that may be more adventurous or experimental than that submitted to the Annual Open Exhibitions. The Club will continue to seek larger spaces, such as the Salmagundi Club, to foster this creative spirit.

Dorothy Barberis

Centennial Exhibition Venues

Philip and Muriel Berman Museum

Midwest Museum of American History

Hartwick College

The Water Mill Museum, Water Mill, New York. Site of the first CLWAC Members’ and Associates’ Exhibition

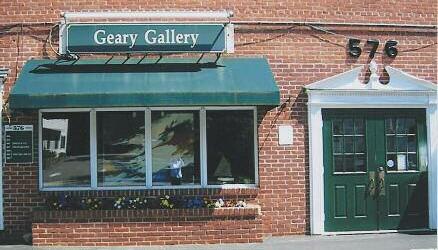

The Geary Gallery, Darien, Connecticut Site of the second CLWAC Members’ and Associates’ Exhibition

The 100th Annual Open Exhibition at the National Arts Club in the Fall of 1996 was a great success, with record turnouts and sales of $13,000. Elyse Topalian, Deputy Chief of Communications at The Metropolitan Museum, spoke at the Benefit Reception, and Kevin Avery, Associate Curator of American Painting and Sculpture, did the honors at the Dinner. Edith Lorillard Cowley, a distant cousin of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, was in 1994 invited to be an Honorary Chairwoman for the Preview Benefit (a title she still holds) and provided several interesting articles on her distinguished relative from the perspective of Newport, Rhode Island, where she had a home for many years. This warm connection added a wonderful dimension to CLWAC’s Centennial events.

Recent years have seen the continuation of the strong traditions and associations established by CLWAC. Under presidents Amy Unfried and Eleanor Meier the Club became more adapted to the electronic age, with a website and information on line. The revolution in computerized printing enabled the catalog for the Annual Open Exhibition to be improved in the capable hands of Gaile Snow Gibbs and Carlina Valenti. Additional shows that included Associates were introduced by President Lucille Berrill Paulsen, and President Joyce Zeller enthusiastically explored possibilities for other exhibitions in museums and galleries outside the New York area. In the Fall of 2007 the prestigious National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., invited CLWAC Artist Members to contribute works for their fund-raising exhibition. This museum, opened in 1987, is a major force dedicated to recognizing the significance of women artists, past and present. Recently the CLWAC Board voted to establish an annual scholarship at the Art Students League, reconfirming a relationship that has been significant from the earliest days.

The aim of CLWAC is to use the best of what is now available through modern technology to extend the reach of the Club to as many professional women artists as possible, while adhering to the exceptionally high standards that have distinguished CLWAC’s impressive history.

Carey Boone Nelson, Karin Strong and Edith Lorillard Cowley at the 100th Annual Open Exhibition in 1996