37 minute read

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON COVID

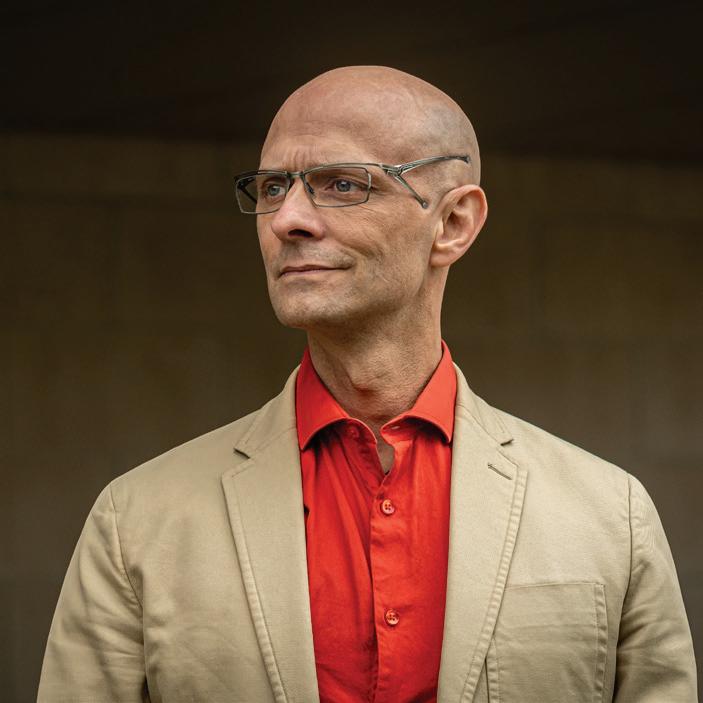

Kim Hellemans is a neuroscience professor at Carleton, chair of the department and the winner of multiple awards for teaching and student support. Her research focuses on mental health, stress and addiction. Jim Davies is a cognitive science professor, director of the university’s Science of Imagination Laboratory and the author of two books, most recently Imagination: The Science of Your Mind’s Greatest Power.

Advertisement

Together, Hellemans and Davies host an award-winning podcast, “Minding the Brain,” which explores cognitive and brain science, covering subjects such as sleep, climate change psychology and emotional expression. They’ve been recording it from separate locations for a few months, so we interviewed them individually and stitched together their conversation. — as told to Dan Rubinstein

PHOTOGRAPHS BY

MARTIN LIPMAN

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON WHAT HAPPENS INSIDE OUR HEADS DURING TROUBLING COVID TIMES

Jim: I first heard about COVID-19 in late 2019 and figured it was nothing. That was fairly rational at the time. Different diseases pop up now and again and they’re usually nothing to worry about. I started thinking it was a real problem in early 2020 when it was spreading around the world and was particularly virulent and people were dying. Kim: I follow a lot of medical and science people on Twitter and started seeing a lot coming out of China in January. It was inevitable that information would trickle out. Right before Reading Week in February, I remember telling a student, “We’ll see how long we’re going to be back for after the break.” It happened so quickly. We went from “It’s far away in China” to “Look at what’s happening in Italy” to the first cases in the U.S. There’s no way it could be in the U.S. and not in Canada.

Jim: I was in Toronto just as everything was shutting down. Hour by hour things were changing. The streets were emptying and we were figuring out how to react. My wife and I were going to see the musical Come From Away and it was cancelled two hours beforehand. Then I was on TVO’s “The Agenda with Steve Paikin,” the last studio interview they filmed. We flew back to Ottawa on a nearly empty plane and shut ourselves in. Kim: Two or three days before the university shut down I was in a departmental chairs and directors meeting devoted to COVID-19.

There was a big event coming up on campus and we weren’t sure if it was going to go ahead. My heart was pounding. I was flooded with adrenaline and I was scared. “All I want to do is go home,” I was thinking. “I want to pack up my stuff, get my kids from school and go home.” There was so much we still didn’t know. It felt like the virus was everywhere and nowhere at the same time, so that was my emotional fear-driven response. Jim: I have an intellectual interest in many facets of our world, and I think about things scientifically to try to understand them. That informs the practical decisions I make with respect to, you know, how much I stay in the house or how often I shop. Science informs my opinions and behaviours, and I try to keep my selfish urges at bay and have everything be determined by my moral compass. Kim: Seven years ago, when I was pregnant with my second child, my husband and I made the mistake of watching the movie Contagion. Since then I have had an acute fear of pandemics. I’m very conscious of illness and am anxious when my kids get sick. As Carleton shut down, I was combing mainstream media and social media for any information related to COVID-19. I was looking at the preprints of journal articles coming out of China, trying to learn as much as I could. That soothed me. When I’m panicking and fearful, I always turn to science. It’s a powerful coping mechanism. I turn to rational information to try to understand what I can control. I can’t control the spread of this virus. I can’t control other people’s behaviour. But I can try to control mine. Jim: I’m immunocompromised, so I wash my hands a lot and try to wear a mask any time I go outside. I believe in modelling good behaviour. The more people wear masks outside, the more social proof it establishes and encourages — the same way that fashion works. I also don’t want to have to think about it. I know how habit works. When something becomes a habit, it becomes the default position. You just do it. Like having a cup of coffee in the morning. It’s not like people decide to have coffee every morning. Even if they’re thinking about something else, the coffee will get made and consumed. Kim: The neural basis of routine is deep-brain basal ganglia. If something is compelling enough to override your routine, it’s going to signal to your prefrontal cortex, which is then going to signal down to your basal ganglia to put a stop to that routine and correct course. Let’s say you’re driving along a highway that you’re on regularly and you kind of tune out. But all of sudden you see ambulance lights in the distance. You’ll put your foot on the brakes. That’s kind of what happens on a daily basis. Routines and habits are good and they’re soothing. I have an exercise routine, a work routine, a home routine. But you need to have the flexibility to get out of those and adapt to the current scenario.

Jim: The function of habit in the brain is to make space for your conscious thought, your cognitive processing, your goal-directed behaviour. You can really only think about one thing at a time. But because you need to do more than one thing at a time — like walk and breathe and talk — there’s this habit system that runs those processes and controls your body when your cognitive system is occupied with other things. The problem is if you’ve got a bad habit, you can’t rely on your cognitive system to always prevent you from engaging in it, because at some point you’re going to be distracted and the habits will take over. So curating your habits and trying to replace the bad ones and encourage the good ones is necessary for good behaviour. Even without the pandemic, our lives are constantly changing and you have to end old habits. Your body tries to respond to the environment the best way it can. The reason we develop bad habits is because we have some natural instincts that aren’t great in our modern-day environment. That’s why eating M&Ms every day is an easy habit to have because sugar has been, for the vast majority of human existence, extremely rare. Developing a habit of eating sugar if you could was a great idea. Modern Canada is not suffering from caloric restriction, yet we’re still energy saving creatures. Kim: The society we live in today is very different from what it was in 1920 and 1820. It’s often massive events — industrialization, World War I, World War II, economic collapses — that shake us up. Society is being disrupted now on a massive scale and we’re altering our behaviours. I’m fascinated by the sociology of it. What are we changing that is never going to go back? Also, what is going to be disrupted for the better? When we think about teaching going online, for example, we’re also thinking about equity and how to support students from marginalized communities and

In their "Minding the Brain" podcast — which won the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada People's Choice Award for Favourite Canadian Science Site in late 2019 — Carleton professors Jim Davies and Kim Hellemans interview each other about the brain and mine their complementary research backgrounds

students who struggle with certain modalities of learning. What we’re doing could actually benefit certain populations if we keep them front and centre. That might sound a little Pollyanna, but if we don’t consider positive outcomes we run the risk of becoming incredible cynics and succumbing to despair. Jim: When you’re dealing with bad uncertainty — when you don’t know how bad something is going to be — that can cause anxiety. Sometimes, in psychology experiments, people prefer to get a more intense electric shock then an unknown amount of electric shock, even if the intensity would likely be lower. That indicates there’s a value to certainty. Also, uncertainty keeps our minds thinking about things and increases our emotional

response. In artistic works and in religion, where there are mysterious things that are hard to understand, your mind tends to obsess over them, in either a good or a bad way. An ambiguous ending can be a beautiful thing and your mind won’t let it go. If the ending is a little too wrapped up, it’s satisfying in the moment but your mind tends to forget it because there’s nothing really there to figure out. So uncertainty generally causes your cognitive system to think about things over and over again. If it’s a fearful uncertainty, you’re going to be re-experiencing negative emotions, because your mind is constantly returning to those ideas, and that can border depression. Kim: One of the best mechanisms to stave off fear and anxious worry is to focus on today, on what’s happening today. We have this wonderful prefrontal cortex that allows us to time travel: it allows us to think about the past in order to plan for the future. Some say this is the root of our intelligence because our cognitive capabilities of planning for the future ensures our survival. But it may also be what is at the seat of a lot of mental health disorders, because when you think about rumination and worrying, it’s about lamenting the past and worrying about the future. So the best way to keep the prefrontal cortex in check is mindfulness — focusing on the present day, the real, the here and now. There’s also the concept of “grounding,” of thinking about what you can control. You can control how often you wash your hands and you can try to maintain physical distance. Your reaction to things that you hear about? You can’t control that. Another tip I’ve heard from psychologist friends is that if you’re susceptible to worry and rumination on the uncertainty of tomorrow, then spend 15 minutes every day thinking about or writing down all your fears and concerns. Then that’s it: 15 minutes and you’re done. You’re kind of relieved of your worries. Jim: There’s a belief out there that in hard times people get really selfish and start turning on each other. But under conditions where people feel that we’re all in this together, the opposite happens. You get a remarkable kind of community building. Sometimes people look back at a food shortage or a power outage or a natural disaster, such as a flood, and see that they were hard times but they also reminisce fondly about the incredible feeling of mutual brotherhood that arose. This pandemic has inspired that. You see people getting to know their neighbours a little bit more and helping each other. Kim: We’re seeing the uptick in cases of COVID-19 because I think people are getting physical-distancing fatigue. As a species, we are social. Obviously, this exists on a continuum, but most people need some socializing. Are Zoom and other digital proxies enough to keep us going? I don’t think so. We need human interactions and we’re fighting against that inherent drive. I’ve got two lovely kids, an amazing husband, and my parents and my sister and her family are also in my bubble. I have a very busy work life. All of this can maintain me, to a certain extent, whereas 20-year-olds who are unpartnered, who may be out of a job, who are not currently in school, they’re driven to hang out and be social. They’re going to bars. If I were 20 that’s where I would want to be too. I think we need to recognize that there is an inherent human desire to be social. This is the challenge. It’s not my problem to solve, and holy crap am I glad it’s not. But we need to figure out a way to live with this virus in the next few months, maybe years, that allows us to be in social environments. Jim: It’s comforting to know that when things go bad, it’s not just every man for himself, but a lot of the changes we make as a species are situational. People want to get back to normal and will start giving one another the finger on the road again. I don’t think the feeling of community that’s engendered by this pandemic will last. The bubonic plague had enormous repercussions far beyond what we’re talking about now. It ended serfdom because so many people died and there weren’t enough serfs around and suddenly everyone’s work was valuable and everyone started getting paid. But that has nothing to do with the building of community. Disasters of the past changed society in a zillion ways, but their contribution to progress is very complex. This pandemic is bad, but it could be way worse. There’s an argument to be made that we would never have prepared for the one that’s going to be way worse if we hadn’t had one that was just a little bit scary first. Maybe we’re actually inoculating our psyches and our research priorities. We might actually start preparing for it. Kim: We need to gather information. This is what me and my colleagues are doing. I do research on university populations and their mental health. We need to find out how they’re doing. Right now, we’re

seeing if people who had pre-existing conditions are suffering the most, or is it everybody? We’re tracking them through time. We’re looking into whether we’re seeing increased rates of problematic substance use and, if so, how can we respond? How can we best provide that circle of care? If it’s virtual, what are the best virtual means to support students and people in general? We need to listen and put money towards this. Because mental health has not, historically, been a space that has been sufficiently funded. But maybe we’re going to hit a crisis point. And people like me need to keep advocating for mental health awareness and keep ensuring that the voices of people with lived experience are heard. Jim: At a government level, this is a good time to push through legislation to increase support for mental health. My American friends are shocked because they think that Canadian medicine is socialized, but it doesn’t cover therapy or drugs. The two things that help with mental health are therapy and drugs. So, basically mental health is not covered by our so-called socialized medicine. I think that’s a real oversight. Kim: The cure cannot be worse than the disease. The factors that are contributing to ill mental health right now are social distancing and the fears and concerns of people without jobs, without support, without access to services. We know when your mental health is suffering, you’re getting lots of proinflammatory factors coursing through your body, which makes you more susceptible to disease. There’s a reason why mental health and physical health are so interrelated. When somebody is not doing well mentally, they’re more at risk. We’re already recognizing that COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting people from marginalized populations. Mental health is a big piece of that. I feel the burden of

responsibility for advocating for mental health among students, and also the burden of continuing to provide excellent educational opportunities for my students and buoying their journey, because they are more vulnerable and at-risk and they’re facing the worst economic prospects in generations. I also feel a certain amount of responsibility to be an advocate for science, period. There’s a vast amount of misinformation and politicized information out there, and I need to chime into the conversation about what’s fact and what’s evidence and what’s not.

Jim: During the pandemic people might be paying maybe more attention to science than they normally would, but I’m not convinced that faith in science has been declining. I haven’t seen good evidence for that. In Steven Pinker’s book Enlightenment Now he makes the case that in every single way that you can think of the world is getting better and has been over the last hundred years. Even fake news. People forget that fake news was way more rampant than it is now. The very fact that people even know what fact checking is, the fact that we even have the reflection to be able to even have a concept of fake news, suggests that society is smarter than it used to be. The only things that seem to be getting worse are social capital in the industrialized world and environmental destruction.

Kim: I had a moment in the summer when I realized that I probably wasn’t going to be on campus for a while. It made me sad. I value being around students and my colleagues and have grown to appreciate them more. I’m sure there are some people who are out living their best lives and couldn’t be happier to be away from others, but I am genuinely sad. Because of my role at Carleton and who I am, I’m usually all over campus, meeting with lots of different people, creating deep friendships and strong collegial relationships that I just can’t replace. Video calls are no substitute for coffee chats and bumping into one another in the tunnels. I’m hopeful, though. I know my emotions are going to be waxing and waning. The way I cope with that is I acknowledge it, I label it — here’s what I’m feeling — and I move through it. Jim: The summer for me was not that much different because I usually just sit at home working all summer anyway. I wrote a book, my third, which is coming out in early 2021 and is going to be called Being the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are. It’s about the science of productivity, happiness and morality. If you want to be the best person you can be, how do you be maximally productive, maximally happy and a maximally good person? I didn’t change the book much after the pandemic started. In the part about productivity, I talk about research into differences between working at home and in an office. Studies show that at the office you’re more creative and at home you’re more productive. Being with people and having casual encounters helps you hash out ideas. But if what you’re doing is relatively cut and dried, then working from home is better. You know what you need to do and just need to do it. ■

SURROUND SOUND

MUSICAL MARVEL JESSE STEWART GETS THE BAND

BACK TOGETHER IN A UNIQUE WAY

BY JOSEPH MATHIEU

PHOTOGRAPHS BY

FANGLIANG XU Jesse Stewart is an amateur. He’s a multi-talented performer and composer, sure, as well as a Juno Award-winning percussionist and a music professor at Carleton. And he has built more instruments than he can count, including a xylophone made of ice and another from books. But Stewart is an amateur, nonetheless, in the truest sense of the word: a devotee, an admirer. He is in a steady state of awe at the melodies and rhythms hidden inside everything, just waiting to be tapped out.

Under the banner of his interdisciplinary We Are All Musicians (WAAM) project, Stewart has long sought collaborators among people who have limited opportunities to make music. His latest creation, WAAM WEB — 48 aluminum discs built into a modular wooden frame, and an app to play them — is a natural progression in an increasingly

Jesse Stewart plays a prototype of his WAAM (We Are All Musicians) WEB instrument, a set of aluminum gongs and electromagnetic strikers that people will be able to control from remote so they can interact musically with one another

digital world, allowing Stewart to orchestrate inclusive online jam sessions. The largest disc is as wide as a yoga ball; the smallest has the diameter of a grapefruit. Mallets triggered by electromagnetic strikers are poised over the grey metal gongs, waiting for a command from … anyone, really. Which is the point. “Music has the capacity to bring people together,” he says, “even when it is mediated by computers and the internet.”

In the Before Times, Stewart was doing just that across the Carleton campus and beyond. He regularly staged pop-up interactive music installations and worked, for example, with patients at Ottawa’s Saint-Vincent Hospital who had limited motor control. Because it’s likely that hospitals and care facilities will be the last places to reopen to non-essential activities, Stewart applied to the university’s COVID-19 Rapid Response Research Grants program to get the band back together in a unique way.

Stewart’s first few weeks of coronavirus quarantine consisted of recovery and rediscovery. After a successful operation to remove a benign brain tumour in February, he uploaded a musical video to Facebook every day for 40 days. The idea was to offset bad news and boredom and to practice doing what he loves: making music out of anything, from mixing bowls and saw blades to bicycles, floor tiles, canoe paddles and even rock core samples. (Stewart once performed a concert using a cardboard box.) Next, with the COVID grant, he built the WAAM WEB prototype and tuned the four dozen gongs.

Not only does Stewart believe that anything can be a musical instrument, he’s also convinced that anyone

can be a musician, no matter their skill level or abilities. WAAM WEB’s online interface allows people to interact and control the percussion system 24 hours a day. Shriya Satish, a Carleton computer science master’s student, designed the instrument’s interface with a video game engine, and local graphic designer firm Stripe Studios helped with coding. Players can tap or click on their computers and hear the notes made by the gongs through a live multi-camera video feed.

People who can’t move a mouse or touch a screen can participate via Adaptive Use Musical Instrument (AUMI) software, which allows users to play sounds and musical phrases through movement and gestures. AUMI was developed in 2006 by American composer and improvisor Pauline Oliveros, a good friend of Stewart’s who passed away in 2016. The tool is used by musicians and educators throughout North America to let children and adults with disabilities improvise music.

One of the big questions about online musicmaking is whether it can build bridges between disparate populations. “To what extent,” wonders Stewart, “can it actually foster a sense of community that’s not based on sameness but rather on difference?” When it’s ready later this year, WAAM WEB will allow people young and old, with diverse bodies and minds, from different backgrounds, to interact musically with one another. Non-musicians who have never played an instrument might think, “Oh, I’m making this sound.” But Stewart will likely smile and say, “No, you’re making music.”

Anyone can be a musician, after all. Even an amateur. ■

PRACTICE MAKES

PERFECT

CARLETON’S NEW WOMEN’S

BASKETBALL COACH PREPARES FOR

THE UNCERTAIN SCHEDULE AHEAD

BY ELLEN TSAPRAILIS

PHOTOGRAPH BY

CHRIS ROUSSAKIS

The melodic rhythm of basketballs bouncing and running shoes squeaking on the hardwood floor reverberates through the Ravens’ Nest gym in Alumni Hall on an early September afternoon. But when the masked 41-year-old speaks, the sounds go silent mid-pivot. Even though Dani Sinclair, the new head coach of the Carleton Ravens women’s basketball team, has yet to lead her squad into a game — and may not do so for some time, amid one of the most unconventional starts ever to a coaching job — the players’ respect is already apparent.

Sinclair, who had been behind the University of Victoria Vikes’ bench for eight years, started at Carleton on May 1. She was introduced by video from the west coast and oversaw online team meetings and individual fitness workouts from remote until August, when players were permitted to begin practicing. They can remove their masks when they’re on the court — Sinclair keeps hers on — but must maintain distance from their teammates. Fortunately, the gym has eight hoops, so there’s plenty of room to spread out, and the balls are sanitized after each session. The backdrop to these safety protocols, of course, is Ontario University Athletics’ decision to cancel all varsity sports until at least April 2021, in line with provincial public health guidelines.

Because practices are an hour shorter than they used to be and players cannot scrimmage, Sinclair is instead focused on basketball fundamentals: shooting, passing and ball handling. She also has more time to analyze video with the team and discuss strategy. “We haven’t got bogged down by what we can’t do,” says Sinclair. “Timelines are different, but I can still plan a season, and we’ll continue to challenge our athletes in whatever ways possible. We usually have to balance skill work with putting in team systems. Now there’s a real opportunity for these women to get better both offensively and defensively.”

The ability to build competitive spirit — even in this stifled environment — has defined Sinclair throughout her basketball career. Growing up across the street from the University of Guelph, her family would rent out their basement to students. One of those students, Caroline Kealy, played varsity basketball and helped coach

Sinclair’s Grade 8 team. Kealy taught Sinclair how to shoot and instilled a love of basketball while she practiced every day on her driveway. “I played every sport I could until I was out of high school, but I was always pulled just a little more to basketball,” says Sinclair, who was a national rookie of the year and a provincial all-star at McMaster University for three seasons before transferring to Victoria, where she captained the Vikes to a national championship in 20022003 and was named a first-team All-Canadian in 2003-04. “I love how many different skills are involved and love the pace of the game. There are so many nuances; if you want to be the best, you can never stop working on your game. I loved that idea as a player and still do as a coach. The opportunity for growth is infinite.”

Sinclair, who had wanted to be a teacher as a kid, began coaching with Basketball BC in 2004. A string of assistant roles, including stints at Dalhousie University and with the national women’s team at the 2011 Pan American Games, paved the way to her head coaching position in Victoria. The Vikes women’s basketball program is incredibly successful — winning a record nine national titles — but Sinclair was drawn to Carleton by the opportunity to help develop a team that captured its first Canadian championship in March 2018 and to work with director of basketball operations Dave Smart.

“There are very few opportunities for professional development in this job, and I don’t see much better than working with Dave,” says Sinclair, who moved her three young sons across the country to come to Ottawa and has relatives within driving distance. “It’s a good fit for me because I’m also pretty intense as a coach. I have experience working in a program where there were extremely high expectations not just of success, but of working hard to earn success. I wholeheartedly believe that sports can develop resiliency and character in a way that not many other experiences can. I’ve benefited so much from basketball and still do today, and I love seeing how that gets passed on.”

No wonder the players stop dribbling and shooting to listen closely when their newfound masked mentor speaks. ■

Carleton women's basketball coach Dani Sinclair and forward Emma Kiesekamp at a physically distanced practice in the Ravens' Nest. Opposite page: Sinclair in competitive mode behind the bench with the Victoria Vikes (photograph courtesy UVic Vikes Athletics)

Reality Fiction

CARLETON ALUMNUS SALEEMA NAWAZ’S NEW NOVEL EERILY PREDICTS THE PANDEMIC

It was ten minutes before the start of his shift and Elliot was hungry. Half of the businesses in Washington Heights had shut down in early October, but the restaurant closures were the biggest pain in the ass. Elliot had been forced to revive cooking skills he’d repressed since college: scrambled eggs, pasta, sloppy joes. There was a booming commerce in food delivery for intrepid couriers, but sitting and waiting at home reminded him too much of his quarantine. Now even the grocery aisle at the drugstore was picked over. He leaned down to inspect a lone instant ramen bowl on the bottom shelf while a woman in a purple raincoat edged over to move away from him. He noticed she had peanut butter and pickles in her basket, and his stomach spasmed.

The centre display of Halloween candy at the front of the store was the one thing left untouched. Usually there’d be slim pickings the day after Halloween, but this year the mayor had called off trick-or-treating — just in case there was anyone living under a rock somewhere who still wanted their kids to go door to door in the midst of a pandemic.

Elliot grabbed a fifty-piece variety box with Kit Kats and Milk Duds. Better to get fat than to starve.

Bryce loved Kit Kats. Elliot’s partner had come down with ARAMIS [Acute Respiratory and Muscular Inflammatory Syndrome] after they’d worked a quarantine relief shift at a big apartment building with sixty confirmed cases. Quarantine relief was a constantly evolving role that entailed food delivery, warning off visitors, and, increasingly, issuing tickets to people registered under a Q-notice who refused to stay home. Though quarantining was technically still voluntary, the city’s top medical advisors had recommended enforcement given the long incubation period of the virus. For police officers like Elliot, this meant trying to strike a delicate balance between respecting the personal liberty of thousands, and guarding against the potential damage that could be wrought by a single infected individual on an ordinary day. What happened to Bryce was a reminder of how badly — and easily — things could go wrong. A feverish, stir-crazy woman adamant on leaving the building had pulled off his mask and coughed in his face to prove she wasn’t infected. Forty-eight hours later, Elliot had watched as her body was carried out in a biohazard bag, while Bryce stayed home under his own Q-notice. A week later, he was symptomatic. Public visiting hours at all hospitals had been suspended, although according to the latest daily update from Bryce’s wife, he was still conscious but breathing with a ventilator.

The self-checkout kiosk was slow; in the store’s far corner, an idle cashier blinked up at a wall-mounted television blaring ongoing coverage of the deadly aftermath of the big fundraising concert in Vancouver. Even when people were trying to do the right thing, Elliot thought, things could still go spectacularly wrong. He stood well back from the person ahead of him in line. It was no longer considered polite to get closer than three feet of someone, though it made for some unruly queues that nettled his sense of public order. Behind him, there was a scraggly row of gloved and masked customers extending all the way into the shampoo aisle.

Everyone in line, Elliot realized, looked like they were steeling themselves for the worst. ■

Excerpted from a chapter set in November 2020 in Songs for the End of the World by Saleema Nawaz. Copyright © 2020 by Saleema Nawaz. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Gri oL eGri oL e

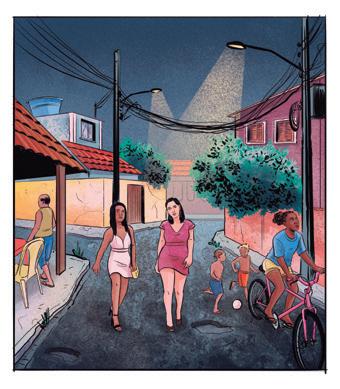

STORIES OF SEX TOURISM STORIES OF SEX TOURISM IN BRAZIL IN BRAZIL

WRITTEN BY Marie-Eve Carrier-Moisan

ADAPTED BY William Flynn

ILLUSTRATED BY Débora Santos

Behind the Headlines

From Gringo Love: Stories of Sex Tourism in Brazil (University of Toronto Press, 2020), a graphic non-fiction book by Carleton anthropology professor Marie-Eve CarrierMoisan, adapted by William Flynn and illustrated by Débora Santos.

THE KU KLUX KLAN IN CANADA

ALLAN BARTLEY

FORMAC

Looking in

the Mirror “You have to take

advantage of what opportunities come your

Hate has a name. Hate has a A native of Grenada, Jennifer Hosten trained with the BBC and was a broadcaster and airline hostess beway. They’ll come in forms you would never fore winning the 1970 Miss World competition. She imagine, and they’ll take face. Hate has an address. It was a high commissioner for Grenada in the midst of its revolution, and subsequently enjoyed a career as you places you would never expect to be.” a Canadian diplomat and trade specialist. She also lives in Canada. The Ku Klux founded and ran a successful inn in Grenada, and now practices as a registered psychotherapist. A mother of two, she lives in Oakville, Ontario. –Jennifer Hosten Klan’s more than one-hundredVisit us on the web at sutherlandhousebooks.com

year presence in Canada demonstrates how hate lived

£18.00 / $22.95 USD / $26.95 CAD ISBN 9781989555279 90000 >

@ sutherlandhousebooks and flourished and still endures Printed in the U.S. Copyright © 2020 The Sutherland House Inc. 7819899 555279

in the nation sometimes known as the Peaceable Kingdom. Our neighbours were partly to blame, but Canadians can also blame themselves. “Because we believe that it can’t happen here, we are too hesitant to talk about the way in which some people — and politicians — are already admiring the reflection they see when they look south,” novelist Alexi Zentner wrote in the Globe and Mail in the summer of 2019. “We think of virulent hatred as a thing that comes from the history books. And yet, the history books are coming to life again.” The challenges of writing a book on the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Canada go beyond creating a narrative. There is the concern that to write about hate is to condone it. To write about the leaders and their followers runs the risk of glorifying them or ridiculing them or magnifying or minimizing their ideas and impact. The odious reality of the Ku Klux Klan and its imitators over the decades speaks for itself. We need to confront that reality. ■

From the preface of The Ku Klux Klan in Canada: A Century of Promoting Racism and Hate in the Peaceable Kingdom (Formac Publishing, 2020), by Allan Bartley, an adjunct political science professor at Carleton.

MISS WORLD 1970

JENNIFER HOSTEN

Breaking Barriers £18.00 $22.95 USD $26.95 CAD

1970 was the last year of the Beatles and the first year of the supersonic Con-

My master’s thesis, on the effect corde—a time of new possibilities and social upheaval, and Jennifer Hosten, a young airline hostess from the Caribbean

island of Grenada, was as surprised as any-

of the North American Free Trade one to find herself in the midst of it. After winning a Miss Grenada contest, she travelled

to London for the 1970 Miss World pageant and arrived Agreement (NAFTA), between at Royal Albert Hall determined to make her mark. So, too, did members of the fledgling Women’s Liberation movement. They chose that globally-televised moment

to protest the exploitation of women. They planted Canada, the United States and Mexico, bombs, stormed the hall, and chased comedian Bob Hope from the stage.

By the end of the night, the world had been inon Commonwealth countries in the troduced to both radical feminism and a new ideal of feminine beauty. Ms. Hosten was the first woman of color crowned Miss World.

Miss World 1970 is the story of the craziest and most Caribbean, was published in book form, meaningful pageant ever, an inspiring account of Ms. Hosten’s barrier-breaking win, as well as her subsequent adventures amid a revolutionary coup in Grenada, her which is how my friends in Grenada globe-trotting career as a Grenadian and Canadian diplomat, and her launch of a Caribbean resort in the wake of Hurricane Ivan.

“You have to take advantage of whatever opportufound it. My goal in all this effort was a nities come your way,” says Ms. Hosten. “They’ll come in forms you could never imagine, and they’ll take you places you would never expect to be.”

worthwhile and stable career with the government of Canada, and particularly its international development agency (CIDA). Before I could apply for work in international development, I was persuaded by another branch of the Canadian government to manage an anti-racism campaign, which I did for three years in the early 1990s. I then turned my attention to the field in which I was trained, joining CIDA and working on environmental projects in several developing countries, including Eritrea, Ethiopia, India and Thailand. While there, I was approached by Caricom (short for Caribbean Community) consultants who were formulating options for dealing with NAFTA’s impact on the islands. There was anxiety among English-speaking Caribbean nations that they would be left out in the cold as North America consolidated its trade. My thesis had argued that the appropriate response for the Caribbean region was to integrate its own trade. Otherwise, it would always be waiting for handouts from so-called developed countries. The issue was right up my alley. ■

From Miss World 1970: How I Entered a Pageant and Wound Up Making History (Southerland House, 2020), by Jennifer Hosten — the first Black woman to win the Miss World Title, who later served as Grenada’s High Commissioner to Canada and earned a master’s degree in political science at Carleton.

I was born for the second time on September 20, 2014. In a faux grass colosseum, with five seconds remaining in what would go on to define much of what I am, or was, quarterback Jesse Mills heaved an oblong piece of leather into the sky and Lady Luck stretched my arms low to catch it. As one-twelfth of the offensive unit on the Carleton Ravens football team, we did the improbable — winning the annual Panda Game against our rivals at the University of Ottawa in a dramatic dying seconds comeback — and my new identity took shape. Nate Behar was a football star now. A boisterous and arrogant one. It was not a complex role to assume, nor a mask I ever struggled to don.

NASCENCY

WHO ARE BLACK ATHLETES WITHOUT THEIR SPORTS?

BY NATHANIEL

BEHAR-WALKER

PHOTOGRAPH BY

MARTIN LIPMAN

If that game was my birth, then the 2017 CFL draft was my high-school graduation. Selected fifth overall by Edmonton, I spent two years playing wide receiver out west. Then came free agency and I returned to Ottawa, proud and excited, to join the RedBlacks. Yet 2020 has chosen a new path for us all. Like so many on this planet, my livelihood has been put on pause while we recoil and recover as a society from the ongoing earthquake that is COVID-19. A football player with no season on the horizon. So who am I?

The first time I was born, it was to an Israeli mother and a Jamaican father in London, Ontario. I was darker than the vast majority of my city. Vast majority. My father had the mind and soul of an artist; my mother had the heart and capacity for love of a goddess. But as we all know, that’s not always enough. So she raised me in London, and he coached me on from Toronto. I started football at age six, enthused and motivated. Then it happened.

I was taught as a nine-year-old how Black athletes are seen. I learned from four opponents my age one brisk evening, on the field that until then had been my safe place, that the answer is a nigger. They taught me with loud voices and wry smiles, surrounding me and thrusting the word deep into my heart, to ensure that time wouldn’t soften the jagged edge of their dagger. So how then are the Black men and women of sport to see themselves in a society absent of their sport? A society that puts its knee to the throat of those who look like you, a society that lets you die disproportionately in the hands of health-care workers, a society that locks you away quicker, for less, over and over again. Who can we be when, even while thousands cheer us on, we strain to feel valued past the price of admission? There’s no single blanketing answer, because we are not a hegemonic people. But the one clear answer is that we cannot be silent.

The third time I was born was a long and laborious delivery. The birth certificate reads June 2020, but conception occurred over years of experienced microaggressions, macroaggressions and the online murder-porn stream of Black bodies. Without the physical and emotional outlet of football to bury my head into — a coping mechanism I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve used too often — I saw that silence was no longer an option. As the child of an artist and a goddess, I began to respond the only way I knew how. With words. Sometimes in this form, written in editor-unfriendly run-on sentences, and sometimes in poetry.

No person of a subjugated race wants to grow into an expert on race due to their own subjugation. But as we’ve all been taught in 2020, the universe does not care one iota for what you do or do not want.

This is who I am now. Outspoken and unapologetically me, which is to say unapologetically Black. But not a day goes by that I don’t miss the boy who lived for nine peaceful years unaware that he was seen as less to some for his pigment. And every day, I look forward to the time where all three of me can exist together — looking on at a world that accepts and values me, screaming in joy in my safe space on the field, and writing about a society that invests its energy into love and creativity. But until then, I write in the face of the storm we collectively stare into, as 2020 tests us again and again. Reborn. ■