7 minute read

Making an Impact: John Lewis Mural Celebrates Civil Rights

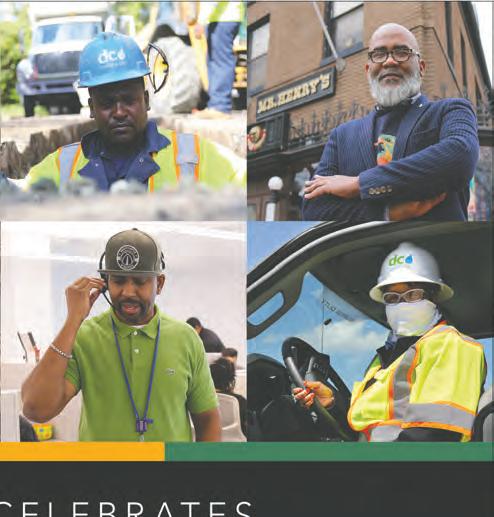

CELEBRATINGBLACK HISTORY

MAKING AN IMPACT

Attendees at the mural ribbon-cutting in front of the section of the mural on the west wall of H.I.S. Grooming (1242 Pennsylvania Ave. SE).

John Lewis Mural Celebrates Civil Rights Legend

A

by Elizabeth O’Gorek crowd gathered Dec. 16 in the parking lot of the Sunoco Station at 1347 Pennsylvania Ave. SE. It is a busy gas station lot, but on that day it was being christened as one of the District’s newest – and more powerful – art galleries.

Along the exterior walls of buildings to the west and north of the station loom dramatic portraits of civil rights leader and former Congressman John Lewis.

On the north wall, a portrait of Lewis’s face is rendered 40-feet high in stark black and white, above his statement “Getting in trouble, Good trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.” Along the west wall of H.I.S. Grooming, images

Artists Mark Garrett and Dietrich Williams speak at the dedication of the mural, Dec. 16, 2021.

from Lewis’s life fill the skies. Lewis is shown in a barber chair.

The barber chair was a place where the civil rights legend was able to relax, tell stories and give advice. The works of art on the exterior of the shop depict both the life of an incredible man but also underline his connection to the culture—and the neighborhood.

The Man

H.I.S. Grooming owner Jared Scott remembers an early morning in 2018, as he stood waiting at his shop window, watching as a shiny black car pulled up outside shiny H.I.S. Grooming early one morning. Scott had reluctantly agreed to give a customer’s ‘boss’ a haircut before opening hours. The door opened and out walked Congressman John Lewis.

CELEBRATINGBLACK HISTORY

Jared Scott shaves the head of legendary Civil Rights leader and Congressman John Lewis at H.I.S. Grooming (1242 Pennsylvania Ave. SE). Courtesy: J. Scott

Most people know of John Lewis. An American Congressman who served Georgia’s 5th congressional district for more than 30 years until his death in 2020, he was the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963 to 1966 and one of the “Big Six” leaders of groups who organized the 1963 March on Washington and led the first of three Selma to Montgomery marches across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965.

Now the legend was in Scott’s shop. But he didn’t act like a legend. “John always paid,” Scott said, “and not only paid, he tipped.” He declined the many offers from other customers to cover his bill. Always humble, Lewis never believed he deserved special treatment. “Once, he even waited,” Scott said.

Michael Collins, Lewis’s former Chief of Staff, explained how that first early morning appointment came about, and how it became one of the famed civil rights leader’s routines. “What happened in the last years of the Congressman’s life, is that he became very particular about his hair. He would start talking about [how] he needed a haircut every week,” Collins said.

Collins scrambled to find the perfect place—somewhere comfortable for the congressman but also convenient for his busy schedule. Scott’s shop was perfect: a true barber shop, just a short ride down Pennsylvania Avenue from Lewis’s home and the Capitol building.

A Relaxing Place

Barber shops have long been a part of American Black culture. Scott moved from Norristown, PA to Capitol Hill ten years ago with a passionate dream and a vision for what the barbershop stands for in the community. He loves cutting hair, he said, but that’s not why he was drawn to the business.

“Truly my passion is the barbershop and the community aspect that it brings. I grew up in a barbershop,” he said.

Collins said that Lewis loved the attention he received from Scott. It became one of the most relaxing times the Chief of Staff could arrange for the Congressman; besides airplanes, Collins said, Scott’s chair was the only place Lewis could fall asleep.

As Scott cut his hair, Lewis told the barber and his staff about the freedom rides and his civil rights work, about fire hoses and dog attacks. Scott recalls Lewis telling him about March 7, 1965, as he prepared to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL. Lewis was beaten bloody. Images from the march prompted public support for the marchers and their voting rights campaign. Lewis told Scott that as he prepared to cross he did not know if he was still going to be alive the following day. “That was a moment that really just stood out to me,” Scott said. “How do you keep going in full capacity when you know that this may be your last moment? And that’s because John just had something more to him.” Scott described how Lewis became a mentor and a friend, someone from whom he sought advice on his personal troubles. He said that Lewis charged him with keeping ‘it’ going.

“I’ll spend the rest of my life nding out what it is,” Scott said.

Black History in Perspective

Scott knew who Lewis was when he walked in the door of his shop —but Mark Garrett didn’t. When he rst met John Lewis, more than a decade ago, the muralist was working as a modeler in a trophy shop, an artist just trying to make a living in his eld. The congressman came in to pick up work ordered by his o ce.

His boss sat him down and gave him an education, Garrett said. “He showed me clips of [Lewis] marching and protesting in the past.” From then on, he prioritized the work he did for the living legend.

But this latest work for Lewis came with fear, too, Garrett said. The work of the civil rights icon was met with violence in the 1960s, and Garrett was aware there were many who would have a similar reaction today.

He did much of his work at night, harnessed to a hydraulic crane. “Some nights I was wondering whether or not somebody who didn’t feel so happy about me doing work on John Lewis might do something.”

Garrett’s fellow creative Dietrich Williams was also processing feelings. Williams grew up on 15th Street in the 1980s and 90s, and has watched the area go through a signi cant transition.

When he was a kid, Williams said, people didn’t want to come east of Third Street, where Lewis lived. He said the quotations from Martin Luther King, Jr. that can be seen in Hill yards are signs of change.

In the course of creating the mural, Williams said, he really felt that change weigh on him. “I realized that a

Now Available ONLINE @ in the Whole Foods Section

The best corn you’ve ever had

Available at

IN THE FROZEN VEGGIES SECTION

100% ALL NATURAL!

NO added sugar, additives, coloring or preservatives

The ‘Good Trouble’ secti on of the mural.

lot of the fabric of what I knew is gone,” he said at the dedication.

Now Williams runs a company that creates public art, with plans for works in Wards 7 and 8. Positive representation of Black lives is critical, Williams said, at the dedication of the mural.

Residents of Capitol Hill will feel the impact of the work he and Garrett put together for years to come, the size of artwork dwarfed only by Lewis’s impact in life. ◆