9 minute read

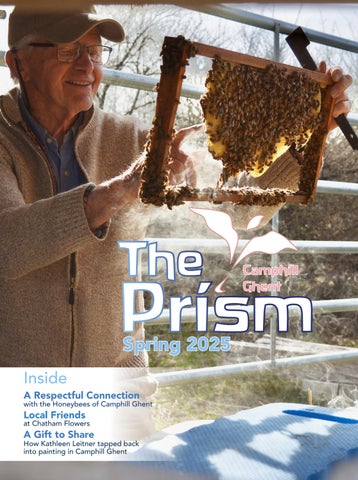

A Respectful Connection with the Honeybees of Camphill Ghent

Much like the elders of Camphill Ghent, tens of thousands of honeybees are building community on our acreage—from the individual roles they take on to benefit the whole, to the homes they build and maintain together. Gunther Hauk has been assisting these bees in their goals for decades while asking very little in return.

“Everything that we have invented in beekeeping in the last 150 years was in our favor: removable frames, boxes that are easy to move, queen excluders, artificial queen raising—

everything has been in our favor to make more money,” said Gunther, who moved himself and his bees to Camphill Ghent a few years ago. “And we never asked once, ‘What do you need?’”

The needs of the bees—their comfort, their natural inclinations, inherent strengths, and seasonal weaknesses—have long been the focus of Gunther’s apiary and biodynamic gardening work, through which he’s woven different seminars and workshops for decades.

Gunther co-founded the Pfeiffer Center for Biodynamic and Environmental Studies in Rockland County, as well as the widely beloved Spikenard Farm Honeybee Sanctuary in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia—the latter a stunning 41-acre sanctuary brimming with nectarand pollen-producing plants that support its resident honeybees and other crucial pollinators. And while both places remain important educational centers within the biodynamic and natural beekeeping realm, Gunther’s dedication and life’s work now directly benefit our community of elders here in Camphill Ghent.

Independent Living resident Christina Bould has been spending recent years delving into the literature on biodynamic agriculture, and has been pursuing opportunities for hands-on education in gardening in Camphill Ghent’s community garden, as well as beekeeping.

“It’s wonderful to have all this activity here. For one thing, we are learning a lot about the bees and where honey really comes from,” Christina said, while accompanying Gunther on April 4th—the first day the bees would take flight after a long winter. “And seeing all this work that Gunther does, it’s really quite extraordinary, and we are very lucky to have that.”

She held in her hands a white sticky board that Gunther had slid out from underneath one of the hives. In some areas, fresh honey had dripped its way down onto the board from inside the hive. Other areas of the white board were bespeckled with red varroa mites, a parasite harmful to honeybees. Commercial-scale honey producers might take swift chemical action against the mites, but Gunther and many other responsible beekeepers monitor mite numbers through the winter—when colonies are especially vulnerable to parasites, fungus, and viruses—before treating the hive with a natural formic acid if mite pressure grows too high.

For Gunther and his students, the point of beekeeping is caring for bees so they can thrive and perform their duties as pollinators. The honey is an additional benefit of keeping bees, but should only be collected if the colony won’t suffer a honey shortage. That said, the honey is exceptional and many believe it aids in building stronger bones, among other benefits.

“I think we would have a lot less osteoporosis and things like that if people eat a half a teaspoon of honey a day. In the evening when you let loose a little bit the honey is really great,” Gunther said, cautioning that the most health benefit from the honey is found when the honey is enjoyed raw or in a beverage that isn’t hot. “I don’t put it in (hot) tea because actually you kill some of the ferments and enzymes.”

It’s a two-way relationship. I am as vulnerable as they are.

Christina says she’s experienced a newfound respect for the bees and consumes their honey in moderation and with admiration.

“The bees have to work so hard for one spoon of honey, so I really always think of them‚ how many trips they have to make,” Christina said, adding that she and the other residents of Camphill Ghent greatly appreciate the honey that Gunther provides in jars. “It’s a wonderful gift to have this taste of honey. It’s so delicious.”

The bees and their brood benefit from many opportunities for wild foraging on our land, including our orchard with its peach, apple, and pear blossoms. What’s more, Gunther seeds our fields with a mixture of clover, dandelion, and heal-all during the colder months, all of which germinate and blossom beautifully for the honeybees.

The apiary building itself is a wooden gridlike structure that protects the bees from strong winds and curious wildlife. A few years ago, after a bear destroyed the first version of the apiary, Gunther raised funds to repair and fortify a new iteration. Inside the protected structure are two standard box hives and a long “top bar” hive that’s more conducive to the rounded comb shape bees produce in the wild. And next to them, a very noticeable standalone tree trunk full of wild bees—a package deal from a neighbor in Massachusetts who needed the bees removed from their property. The tree trunk—with its thick walls and hollow interior—is ideal for bees in all seasons.

“This is the difference between what we have and what they would like,” Gunther said. “This [tree trunk] has about three inches of insulation. They really love it in there.”

The man-made hives in the apiary, however, are padded with straw for temperature regulation, and wrapped in thick canvas sheets that a fellow Camphill Ghent elder sewed for the hives in exchange for a jar of honey; Gunther said she was delighted to have a meaningful task to complete.

Through the colder months, the bees shiver inside the hive to generate heat, maintaining a temperature around 95 degrees Fahrenheit. But finally, on that first Friday in April, the sun was shining and temperatures were in the lower 60s— warm enough to open the hives and let the bees make their way to forage. It’s also the first time Gunther will have the opportunity to examine the comb, and get a more complete perspective of how the colonies faired over the winter—whether there are brood cells, if they produced enough honey stores, and more.

Gunther, with Christina at the ready by his side, filled the canister of his hive smoker with dried aromatic herbs he collected during the growing season. He lit the herbs on fire and prepared to knock.

“The smoke is like a doorbell. I just let them know that I’m coming,” he said, gently puffing fragrant smoke just twice into the hive’s front entrance. He removed the roof of the hive, exposing a welcoming hum. “Hello, girls.”

His first observation is the abundance of red propolis the bees have used to seal the cracks of their home. The bees take the resin-like glue from the buds of trees, where it protects buds from disease and fungus; it provides a similar benefit for the bees. After gently prying the frames free, Gunther slides a frame out of a far end of the hive to reveal a glowing sheet of honeycomb full of cells the bees have diligently capped with white wax. Just a few bees are crawling on it.

“Beautifully capped honey,” he marveled. “They decorate it so nicely over the winter.”

He hands the frame to Christina and chooses a different one from the center of the hive. The cells are much darker—mostly brown— and totally covered in crawling bees. This is a productive neighborhood in the hive. Gunther points around the busy frame of honeycomb.

“OK, there is brood in all stages: larvae, a few eggs, and the capped brood. And the queen could be on here unless she evaded me,” he says while slowly spinning the frame with his fingertips to continue his search. “And that’s OK. You don’t have to find the queen all the time.”

His confidence with the bees is impressive, and so is their lack of reaction. The relationship he builds with the colony will continue as the brood grow and replace the adults.

“I took out the frames. Why didn’t they sting me?” It’s a pop quiz. The answer is the relationship. “I go into where the brood is raised—into their innermost being.”

Gunther says if he were to approach the bees in a suit—with protective gear between himself and the colonies, there’s a power imbalance that will cause concern among the bees.

“A relationship that you build is a two-way relationship. I am as vulnerable as they are,” he says. “They can sting me, and that makes me work more carefully and more respectfully. That’s what we teach at Spikenard Farm.”