6 minute read

OKINAWA IN THE ´50 SENSEI Cecilia Salbuchi

OKINAWA in the ´50

Sensei Cecilia Salbuchi

Advertisement

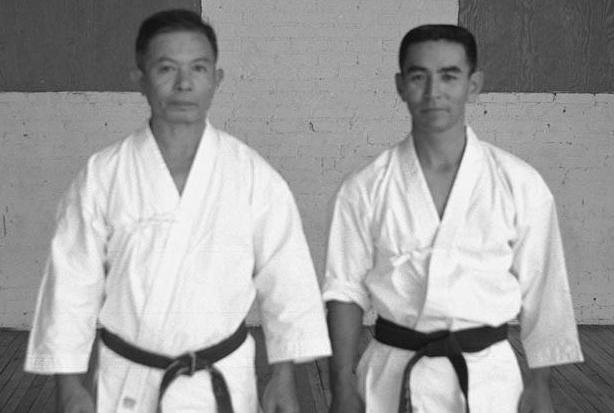

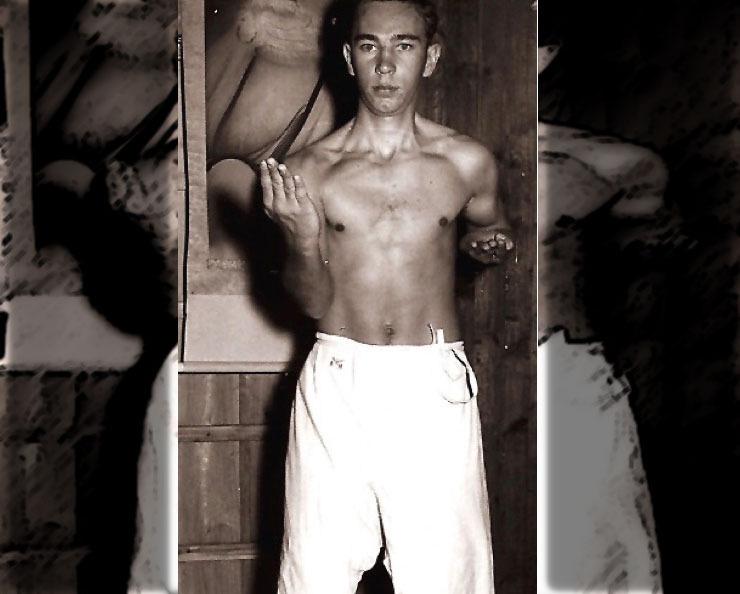

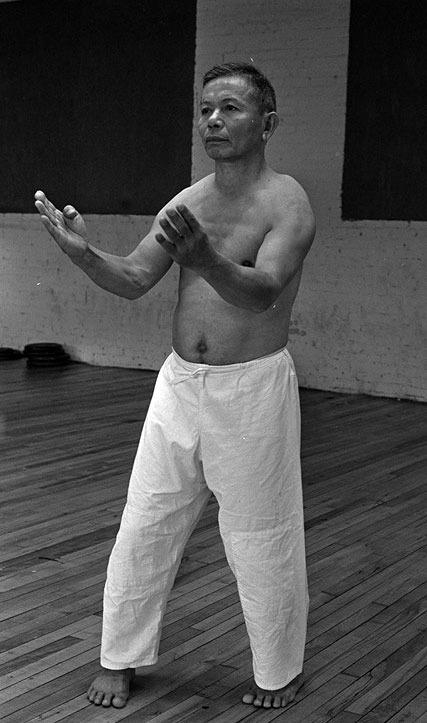

Uechi Ryu training in the 1950s Sensei George Mattson (10th Dan Uechi Ryu, founder of IUKF) was one of the first Westerners to practice and study Uechi Ryu, during the 1950's. As a young American military man serving on Okinawa Island, he spent his spare time seeking knowledge of Karate from legendary masters such as Kanei Uechi Sensei and Ryuko Tomoyose Sensei. An incredible experience. As the years and generations of karatekas passed, many myths were generated around what was a classical training in Okinawa, and Sensei George, among others, shed some light on the subject in articles and posts published in Uechi-ryu.com. As part of our story, I share a little about it. Sometimes the idea arises that the pioneer teachers were outstanding athletes, who performed feats thanks to demanding strength exercises, as well as possessing an elongation worthy of a gymnast. But this is far from reality. Karate classes in Okinawa were full of Karate, nothing more, nothing less. The warm-up included kata techniques, then executing the forms themselves, followed by bunkai, pre-armed or free combat, tai kitae (physical conditioning through striking), and strengthening exercises with elements, designed to strengthen only the muscles. necessary to execute Karate techniques (at least with the knowledge of the time). Classes with Sensei Ryuko Tomoyose lasted between two hours and two and a half hours, being very exhausting. Sensei George made sure to give his all at that time, where he relates that all the time was spent on Karate and not on other exercises. The focus was 100% on Kata training (and its bunkai), and especially on Sanchin. Sensei Tomoyose stated that unlike the Western physical training he knew, in Karate all the strength, speed, coordination, precision and "spirit" came from the practice of Kata. The specific techniques were practiced in the form of exercises, but emphasizing their function in learning the sequences to execute them better within the kata. The skill of the movement as a whole was learned by executing and studying kata, to the point of clarifying that if one isolated the technique from the form, it moved away from the original spirit and became less effective. For example, learning to do “hajiki uke” (repelling block) within a kata would create a different and more effective muscle memory than simply doing a separate exercise where we defend with “hajiki uke” a thousand times. As if the loose techniques were links, and only found their function when joined with the other links to form a strong and mobile chain. Training with Makiwara was allowed, but not greatly encouraged, as we have seen in modern times. Young Americans loved to train by hitting the board until they were sore and exhausted, but Tomoyose Sensei insisted that too much practice could block the proper development of the stroke. Sensei George recalls that his Saturdays were meant to train with Sensei Kanei Uechi himself in his dojo, going through the kata over and over again, under his watchful supervision. Sensei Kanei offered criticism and recommendations to Sensei Tomoyose to better guide the young American. Kanei Uechi Sensei was interested in expanding the style, including the public, so he accepted elements of Okinawan training and any innovation that he believed could help students become better Uechi Ryu practitioners, so they were a little disagreeing with Sensei Tomoyose, who believed in the Chinese method of training that he had learned early on. Tomoyose Sensei's father, Ryuyu Tomoyose, had learned under Kanbun Uechi Sensei himself in Wakayama. There, he recounted, there were no calisthenics exercises as part of the class. He just trained 16

Sanchin and Seisan, pair exercises for bunkai, kitae and free kumite. During the 50's Sensei George learns some additional kata of the style: Kanshiwa and Sechin, and a first pre-armed combat exercise. In 1965 he formally introduces himself to the Kyu and Dan Kumite exercises, as well as finishing learning Kanshu, Seryu and Kanchin. At this time the Jumbi Undo exercises (very few dojos keep it intact) and Hojo Undo (13 exercises) are formalized. Returning to the training of Makinawa, so appreciated by our side of the world, Sensei Breyette expressed in an epistolary exchange with Sensei Mattson, that we Westerners had misunderstood the use. “Okinawa karateka build strength and endurance over long periods of time and much through the study of form and kata, and use equipment sparingly. In many Okinawan dojos, the use of equipment is like using a cure for a particular weakness. If you have weak wrists and shoulders, appropriate use is made of the makiwara and chisi. Weak kicks and poor balance can be corrected and given more focus with the use of the heavy bag. However, for many foreigners, who visit for short periods and see the equipment in use while they are there, go home afterwards and think that such a practice must be constant. Because they see a small fraction of the year's training, what they see they believe to be the norm, so they firmly believe that everyday punching, lifting weights and hitting the bag are all very necessary and very Okinawan! It is true that they saw all that training in Okinawa, but they did not see everything.” Sensei Breyette continues his explanation: “In no dojo that I have seen in the center is there anything set up as compulsory training. I've seen great wrestlers do bag work only occasionally, and the same with makiwara or chisi training, and so on. These only work until a certain sense of skill, looseness and stability in the wrist or hip joints, balance, etc. is achieved. Then work is done on the effect of the application in kata, bunkai and kumite training. The purpose of bag work or makiwara is to feel balance and power in the technique (not doing more bag work) and to be able to apply it with a combat partner or in a street situation!” On the other hand, Sensei Tomoyose spoke that certain jobs should have a balance, a harmony, and that is why it should be to reinforce weaknesses at the right point. An over-development in any one area can lead to an imbalance in others. He highlighted the differences between the original Uechi Ryu and the Okinawan contributions. For him, it was very important to make the story clear. Therefore, the makiwara should be used correctly and in its proper measure: to strengthen muscles and tendons, but not to develop the blow itself, much less for the knuckles. Returning to the present, today we can say that the Okinawan introductions to the arts that came from China gave a particular shape to the training of Karate, and certainly the West will make a dent incorporating its own innovations to the training. But as Tomoyose Sensei pointed out, it is important that we understand where everything came from, how it was trained in the beginning, and how (and for what!) the following elements were added. Time will tell if modern elements and innovations in training have actually been an improvement or not.