20 minute read

A letter from a Benedictine monk

THE DISPOSITIONS FOR PRAYER III: Compunction according to St Benedict and St Gregory the Great

Calx Mariae is pleased to continue the series of letters from a Benedictine monk discussing some of the most important virtues and principles in the Rule of St Benedict – the rule on which the Western monastic tradition and Christian civilisation in Europe were founded.

Advertisement

In the Prologue of his Rule, St Benedict, the patron saint of Europe writes: “We have therefore to establish a school of the Lord’s service, in the institution of which we hope we are going to establish nothing harsh, nothing burdensome. But if, prompted by the desire to attain to equity, anything be set forth somewhat strictly for the correction of vice or the preservation of charity, do not therefore in fear and terror flee back from the way of salvation of which the beginning cannot but be a narrow entrance. For it is by progressing in the life of conversion and faith that, with heart enlarged and in ineffable sweetness of love, one runs in the way of God’s commandments, so that never deserting His discipleship but persevering until death in His doctrine within the monastery, we may partake by patience in the suffering of Christ and become worthy inheritors of His kingdom.”

After looking at virtues like humility, obedience, prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice in the Rule of St Benedict, in this edition we continue with St Benedict’s teaching on prayer.

Filled with the life-giving waters of the Holy Ghost, your soul, O Benedict, gushed forth rivers of wonders that withered up abusive passions. 1 Thus sings the Byzantine Divine Office in praise of St Benedict, based on what St Gregory tells us about him, that he was filled with the Spirit of all the just (Dial II, 8), as well as on the words of Christ that we sing at the Vigil of Pentecost: On the last day of the festivity, Jesus said: He that believeth in me out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water. Now this He said of the Spirit which they should receive who believed in Him (Jn 7:37–39). Moreover, in Psalm 106 we read of the mystery of the withered passions in the words: He hath turned rivers into a wilderness and the sources of waters into dry ground: A fruitful land into barrenness for the wickedness of them that dwell therein. Then, concerning the mystery of new, divine life we read: He hath turned a wilderness into pools of water: and a dry land into water springs.

St Benedict was a true bearer and servant of the Holy Ghost; for this reason, we pray on the octave day of his summer feast: Raise up, O Lord, within thy Church the Spirit which our holy Father Benedict the Abbot served, so that, filled with the same Spirit, we may love what he loved and practice what he taught. One of the most conspicuous ways in which the Holy Ghost was active in St Benedict’s life was in his compunction and frequent prayer with tears, two things which he also energetically recommends to his disciples in his Rule. But we must note that not all forms of sadness qualify as compunction, and not all tears are virtuous. Indeed, some are very harmful.

Just as there is an evil zeal of bitterness which separates from God and leads to hell, so there is a good zeal which separates from vices and leads to God and to life everlasting (RB 73; Dilatato Corde, 98). With these words St Benedict introduces the penultimate chapter of the Rule. In our effort to understand compunction, we could simply substitute the word zeal with sadness in this sentence: Just as there is an evil sadness of bitterness which separates from God and leads to hell, so there is a good sadness which separates from vices and leads to God and to life everlasting. Indeed, there is a good sadness that leads us to God and prepares us for heaven, and this we call compunction; and there is an evil sadness that separates us from God and prepares us for hell, this is the vice of melancholy. Compunction is the work of the Holy Ghost, a spiritual banquet of virtuous dispositions; melancholy is the work of the devil, a spiritual destitution wrought by passions and sinful desires. Speaking of these two kinds of sadness, St Paul says that the sorrow that is according to God worketh penance, steadfast unto salvation: but the sorrow of the world worketh death (2 Cor 7:10).2 To help us understand this difference better, we could translate St Paul’s original text to read, Godly grief leads to an abiding and salutary transformation of the heart; but worldly grief leads to death.

How do we tell the difference between the two? To begin with, we should recognise that all sadness, whether compunction or melancholy, results from some loss, real or perceived. In its initial stages, all sadness is morally neutral,3 but we are the ones who guide it towards either compunction or melancholy. All sadness is about loss: the loss of some important object, the loss of a job, the loss of a house or car, the loss of a pet, the loss of the affection and respect of others, the loss of an important relationship, the loss of love, the loss of a loved one. The sadness can be greater or lesser depending on the object that is lost, on the circumstances that brought about the loss, and on whether or not that which was lost can be recovered or restored in some way.

Now, if our fundamental disposition is one of faith in Jesus Christ, then we will be able to consider these questions reasonably and accurately; we will know if we can do something to regain that which we have lost, and if so, we will pray for the wisdom and fortitude to do just that. If, however, the lost object is beyond recovery, we will see that either that which was lost was not as important as we initially thought it to be, or, if it was, we will be able to come to terms with the loss, to accept the new reality with faith in God’s providential love and submission to His holy will. Moreover, we will let God Himself take the place of that which was lost, and the words of Our Lady will come to pass in us, that He has filled the hungry with good things (Lk 1). Tears are good, says St Ambrose, if you know Christ, 4 that is, if you grieve in the truth and love of God. Grief that is conducted in this manner, that is, in faith,

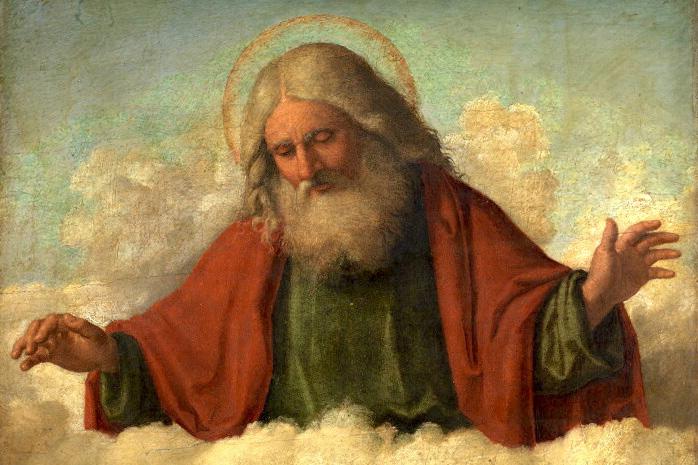

God the Father (ca.1510–1517). Attributed to Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano. Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

has a beginning and an end. It will have its tears, no doubt, but eventually, it will lead to a stronger faith, a more vibrant hope, and a deeper love for God, and this produces both peace and joy. Grief that is filled with faith is not sterile, but active and fruitful; it is not bitter, but sweet and gentle; it is not restless, but generates deep peace and repose in the soul. Such grief is happily transformed into a holy compunction.

If, however, one does not grieve in faith, but rather tries “to go it alone”, without God, mental confusion ensues. One is usually incapable of finding the path out of the dark wood. Things that have relatively small importance take on a disproportionate and unmerited significance. In place of the resignation to God’s will that makes for peace, there is a militant anger that refuses to accept any loss, a bitterness that treats everyone as an enemy at some level. Such grief has lamentably become melancholy. Melancholy of this sort refuses to accept reality, and thus has no end; it superficially limps along without going deeper, without ever facing reality or accepting the truth. Melancholy of this kind is born of pride, and often leads to a crippling self-pity that blames others for the losses it has suffered.

Melancholy can arise from pride in a slightly different manner in the form of self-hate. Someone in this state sees himself as a failure by the world’s standards (not God’s), and consequently despises himself. In this, as in all forms of the vice of melancholy, the influence of the demons is readily visible, for their aim is to make us feel and think that we are hated by God and others. But it is impossible for God to hate us, for according to the words of Scripture that we sing on Ash Wednesday, thou hast mercy upon all, because thou canst do all things, and overlookest the sins of men for the sake of repentance. For thou lovest all things that are, and hatest none of the things which thou hast made (Wisdom 11:24-25; Introit for Ash Wednesday). This melancholy of self-hate may seem both to the one who suffers it as well as to others as humility – as a holy contempt of self; but just how far it is

Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych, right panel (ca.1430–1440). Jan van Eyck. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. from humility is proved by the coldness, indeed, contempt, such a person feels for God.

Genuine humility, on the contrary, is always bound to a deep love for God, and submission to His will.5 The desire to rejoice in one’s own greatness, moreover, leads to bitter grief, since the source of true joy, God, has been abandoned.6

There is another kind of melancholy that desires earthly goods, and is saddened by the absence or loss thereof. Speaking of this kind of sadness, St Gregory the Great says that tears that seek after perishable goods have no fruit7 since they seek to obtain limited and transitory goods – wealth, power, pleasure, or vainglory. People afflicted with this melancholy devoutly submit themselves to the harshest yokes of slavery in order to obtain these things,8 and are yet more miserable if they succeed in their aim, since every worldly good must be anxiously guarded against loss, and must ultimately be forfeited at death. Therefore, the Psalms admonish us: Be not thou afraid when a man shall be made rich, and when the glory of his house shall be increased. For when he shall die he shall take nothing away: nor shall his glory descend with him (Ps 48:17–18).

The sorrow of compunction, however, is as far from melancholy as the East is from the West. Someone pervaded with compunction is not saddened by the loss of temporal things, but by the loss of God. Like the Psalmist, such a person finds consolation in God alone,9 and merits the beatitude pronounced by Him: Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be comforted (Mt 5:5). Such souls consider themselves mere wayfarers and see this life for what it is – a place of pilgrimage and a valley of tears, and are thus filled with a sorrow that is, according to St Gregory, the bitterness of the wise (amaritudo sapientium)10 and the grief of the hearts of the elect (luctus cordis electorum).11

St Gregory distinguishes two basic kinds of compunction: one of fear and one of love. The former is a purification from sin and a protection against it; the latter is a force of spiritual desire that draws us heavenwards: “There are four ways in which the soul of the just man is powerfully moved to compunction: when he remembers his evil deeds,

considering where he was (ubi fuit); or fearing the sentence of the judgments of God and analysing himself, he considers where he will be (ubi erit); or when, carefully considering the evils of the present life, grieving he considers where he is (ubi est); or when he contemplates the good things of the heavenly homeland which, because he does not yet obtain, mourning he contemplates where he is not (ubi non est).”12 Let us take a look at each of these compunctions.

The first two arise from the fear of God, which is the first and foundational gift of the Holy Ghost because from it flow the others which culminate in wisdom, for the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom (Ps 110). The gift of wisdom (sapientia) allows us to have a connaturality with divine things, that is, it allows us to taste the mysteries of faith; the gift of understanding (intellectus) allows us to comprehend these mysteries in their richness and wonder. Having had a taste of heavenly things and understood them at a deeper level, we are then given the gift of knowledge (scientia), by which we better know God and the things He has created, and through the gift of counsel (consilium) God teaches us how to act. Now it is above all through the gift of knowledge that the compunction of fear matures and grows in us,13 for it allows us to see ourselves as we are, with the sins that lead us away from God, but also as created in His image and likeness, and redeemed by the Blood of His Son, and in love called to be holy like Him. Seeing our sinfulness and ingratitude towards God, we are filled with disgust at ourselves and come to hate our sins; but seeing the price the Son of God paid for our salvation, we are given hope to amend our lives and become holy as He is holy.

Thus the gift of the fear of the Lord inspires us to be ever mindful of all that God has commanded, and leads our thoughts to constantly meditate on the hell-fire which will burn for their sins those who despise God, and thus guards us at every moment from sins and vices, whether of the mind, the tongue, the hands, the feet, or the self-will, and checks also the desires of the flesh. This fear gives us a certitude that God is always looking at us from heaven, and that our actions are everywhere visible to the divine eyes and are constantly being reported to God by the Angels (RB 7). It makes us fear the Day of Judgment and fills us with dread of hell, enabling us to dash against Christ the evil thoughts that come into our heart and to confess our past sins to God daily in our prayers with tears and sighs, and to amend them for the future (RB 4). It makes us fear grieving by our evil actions the God and Father who has deigned to count us among His sons, and makes us serve Him with the good things He has given us, lest He disinherit us as an angry Father, or even worse, as a dread Lord, provoked by our disobedience and sins, deliver us to eternal punishment as wicked servants who did not want to follow Him to glory (RB prologue).

Finally, it makes us feel the guilt of our sins at every moment in such a way that we consider ourselves already present at the dread Judgment and constantly say in our heart what the publican in the Gospel said with his eyes fixed on the earth: Lord, I am a sinner and not worthy to lift up my eyes to heaven (RB 7; Lk 18:13). Souls pervaded with this two-fold compunction of fear feel a deep contrition for their sins, and fear being placed with the damned at the left side of Christ, the Just Judge.

Therefore, they make their own the petitions of the Miserere, Psalm 50, that unsurpassed prayer of repentance and contrition; and they beg for mercy as if already present at the Last Judgment, in sentiments that are perfectly expressed in the Dies Irae, that masterpiece of poetic hymnody from the Requiem Mass. In both of these prayers, we see two kinds of divine fear: on the one hand, a servile fear that is in dread of punishment, and on the other hand, a filial fear that shudders at the thought of offending God. The first, servile fear gradually diminishes as the second, the filial fear, increases, for filial fear is an expression of charity, of that perfect love of God which casts out servile fear. 14

As filial fear increases and we enter into the third compunction, so too does our love for God and our desire to be with Him in heaven, and this gives rise to a readiness to labour in this life in order to merit eternal bliss in the next. A great source of consolation for someone in this state is the lovely prayer of the Salve Regina, wherein we turn to Our Lady to console us amidst the inevitable afflictions of this life. Our eyes then look upon this world anew. We see it for what it is: a place of exile, temptation,

toil and suffering, all as a just penance for original sin and for our many personal sins. St Benedict therefore tells us in the opening lines of the prologue that it is through the labor of obedience that we may return to Him from whom we had departed through the sloth of disobedience; for this reason the novice monk should be told all the hard and rugged ways by which the journey to God is made (RB 58). But God in His mercy allows us to see even these sufferings as blessed in their own right, for by them we share in the sufferings of Christ and deserve to have a share also in His kingdom (RB prologue). It is for this reason that St Benedict desired the miseries of the world more than the praises of men, and to be wearied with labour for God’s sake rather than to be exalted by the favours of this life (Dial. II,1). In this he gave proof of the presence of the gift of fortitude, which enables us to bear adverse things in our fidelity to Christ. How abundantly did his soul gush forth rivers of wonder that dried up arrogant passions! Since the source of those rivers were the life-giving waters of the Holy Ghost,15 we can be sure that his love for God increased with every tear he shed amidst the toil and sufferings he endured in this life, exemplifying what St Gregory says about the saints in general, that the more the just soul sweats in the doleful affliction of hardship, the more it thirsts to contemplate the face of its Creator.

Having become so dear to God by his labours, St Benedict was firmly established in the fourth compunction – in which there is no more sorrow, but only soul-piercing joy – and sensed Him close and available to him whenever he prayed. And he tells us the same will happen to us, for when you have done these things, the eyes of our Heavenly Father will be upon you and His ears will be open to your prayers; and before you call upon Him, He will say to you, “Behold, here I am” (RB prologue; Is 58:9). Having been given such a clear perception of God’s sweetness, St Benedict preferred nothing to the love of Christ and desired eternal life with all spiritual concupiscence (RB 4), and since, in this life, Christ is present to us above all in Holy Mass and the praise of the Divine Office that perpetuates the Eucharistic sacrifice, he himself preferred nothing to it, and admonishes us to likewise esteem it above all things. The psalms thus became his most treasured prayers, and he hopes they will for

The Mass of Saint Gregory (before1480). Diego de la Cruz. National Art Museum of Catalonia.

us too – a fitting crown to accompany that last gift of the Holy Ghost, piety, through which we firmly establish our identity as God’s sons and daughters, and can sing: let my mouth be filled with praise, that I may sing thy glory: thy greatness all the day long (Ps 70:8; Introit for Pentecost Friday).

May the Holy Ghost deign to bring about this marvellous work of compunction in our lives too, in us who are as a desert land where there is no way and no water (Ps 62:3). In the Gospel for Pentecost Sunday Our Lord tells us that If anyone love Me, he will keep My word, and My Father will love him, and We will come to him and will make Our abode in him (Jn 14:23). Consider, my dearest brethren, says St Gregory, what a great dignity it is to have as a guest the Lord who comes to our hearts. But let us not receive Him in vain, for He indeed comes into the hearts of some yet does not make His permanent abode in them, for although they perceive the sight of God through compunction, in time of temptation they forget the very thing they perceived while they had compunction, and in this way return to their sins as if they had never shed a tear. 17

ENDNOTES:

1. Antiphon from the Office of Orthros, or Lauds: Ναμάτων ζωτικῶν τοῦ Θείου

Πνεύματος, πλησθεῖσα Βενέδικτε ἡ ψυχή σου, ποταμούς θαυμάτων ἔβλυσε, νοσημάτων ξηραίνοντας ἐπήρειαν. 2. ἡ γὰρ κατὰ Θεὸν λύπη μετάνοιαν εἰς σωτηρίαν ἀμεταμέλητον κατεργάζεται• ἡ δὲ τοῦ κόσμου λύπη θάνατον κατεργάζεται. Quae enim secundum Deum tristitia est, poenitentiam in salutem stabilem operatur: saeculi autem tristitia mortem operatur. 3. See St. John Cassian, Conference 6, ch. 3; Dilatato Corde 438-441: We must then believe that in things which are merely human there is no real good except virtue of soul alone, which leads us with unfeigned faith to things divine, and raises us constantly to adhere to that unchanging good. And on the other hand we ought not to call anything bad, except sin alone, which separates us from the good God, and unites us to the evil devil. 4. Exposition of the Holy Gospel According to St. Luke, X,161 5. The Moralia (Commentary on Job) by St Gregory the Great, IX, 56. There are some who have lamentation but do not have humility; they weep in affliction, but in their very tears they are either arrogant towards their neighbour or rise up against

God’s providence. 6. Moralia, XII, 27. 7. Moralia, XI, 13. 8. Moralia, XX, 39. 9. Ps 76 :4. I remembered God, and was delighted. 10. Moralia, XVIII, 66. 11. Moralia, XV, 68. 12. Moralia, XXIII, 41. 13. See St Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, IIa-IIae, Q. 9, A. 4: Right judgment about creatures belongs properly to knowledge. Now it is through creatures that man’s aversion from God is occasioned, according to Wis 14:11: Creatures … are turned to an abomination … and a snare to the feet of the unwise, of those, namely, who do not judge aright about creatures, since they deem the perfect good to consist in them. Hence they sin by placing their last end in them, and lose the true good. It is by forming a right judgment of creatures that man becomes aware of the loss (of which they may be the occasion), which judgment he exercises through the gift of knowledge. Hence the beatitude of sorrow is said to correspond to the gift of knowledge. 14. RB7;1Jn 4:18. 15. Moralia, XV, 20: In the Gospel the Lord says: He who believes in me, as the Scripture says, streams of living waters will flow from his belly (Jn 7:38). The streams therefore are the gifts of the Holy Ghost. Charity is a stream, faith is a stream, hope is a stream... 16. Moralia, XVI, 32. See also Ps 93:19: According to the multitude of my sorrows in my heart, thy comforts have given joy to my soul. 17. St Gregory, homily on the Gospel of Pentecost for Matins, III nocturn 5.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY!Digestvoice of the family Confronting the challenges to authentic Catholic teaching on the family

A weekly commentary on contemporary threats to life and the family keeping Catholic families up-to-date with developments which affect them.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY!

www.voiceofthefamily.com

The Annunciation (ca.1426). Fra Angelico. Museo del Prado, Madrid..