15 minute read

Yamaha

Elemental Composition in Ensemble Settings

by Tiffany Ou-Ponticelli, CODA President

Advertisement

The general sentiment after the last two years among ensemble directors is that of exhaustion and depletion. Most California schools were in-person for the 2021-22 school year, and while it was certainly less isolating than teaching on Zoom, it’s certainly still been a year full of challenges. From my post as a middle and high school orchestra director, the shining light throughout the year was being able to play together with immediate gratification, and to once again foster creativity as a group. In my opinion, some of the best parts of ensemble time come from not only rehearsing and performing, but in allowing students to take the lead in creating together. There is also evidence to show that creative music-making may enhance student confidence in their ability to participate meaningfully in music composing, and may increase student motivation and engagement (Hogenes, et al., 2016). Composition can also have implications for student self-expression: “Missing in the formal education of our players are opportunities to create new music that is culturally meaningful and self-reflective” (Allsup, 2003, p. 24). In this article, I humbly offer you some suggestions for integrating group composition in the traditional large ensemble setting.

The examples used in this article are from my 7th and 8th grade combined orchestra class. While I teach strings, these concepts can certainly apply to traditional band settings as well. I draw on ideas from Orff-Schulwerk elemental composition structures that I believe can be applied to the large ensemble setting as well.

Composition in Group Settings

As an ensemble director, I am working with dozens of students at a time, with a performance schedule that includes school concerts, tours, and festivals. The majority of our class time is indeed spent on technique development and preparation for performance. However, as part of the “Creating” category of the current National Association for Music Education’s standards, students in secondary ensembles should be able to “compose and improvise ideas for melodies, rhythmic passages, and arrangements for specific purposes that reflect characteristic(s) of music from a variety of historical periods studied in rehearsal” (National Association for Music Education, 2014, p. 1). Researchers studying group composition have found that composition assignments allow for newfound student creativity and ownership of their music education (Wiggins, 1999, Priest, 2006; Hogenes et al., 2016).

There are a number of logistic challenges regarding composition in group settings, including space and technology limitations. In the examples for this article, I assigned small chamber ensemble groups that were mixed in musical experience and instrumentation. Students were encouraged to keep their instruments out, and exploration on their instruments was encouraged. One “scribe” per group also had their Chromebook out (our school is 1:1) and was in charge of notating the work session in NoteFlight (in this instance, students had individual accounts through NoteFlight Learn, but there are many cloud-based notation software options available).

The limiting of the number of devices is intentional to maximize in-person communication; the role of the scribe can be rotated per session.

Theme and Variations Form

An immediate challenge with student composition is the lack of structure. Teachers may find success in using a more structured compositional style for this kind of creative group assignment. Hopkins (2013) examined composition in middle school orchestra in a case study with two veteran string teachers. In the study, two seventh-grade classrooms at different schools participated in Theme and Variations composing projects. By employing the Theme and Variations framework, students were given appropriate amounts of both scaffolding and freedom. The project in this article was executed with many students composing in the same room, with each group composing their own variations. The small group pieces were then combined into a larger orchestral work to be performed.

For this project, the class together examined examples of Theme and Variations forms and made lists of musical properties that could be varied. These reference lists were then applied to the theme of “Simple Gifts.”

Elemental Composition - Orff-Schulwerk Principles

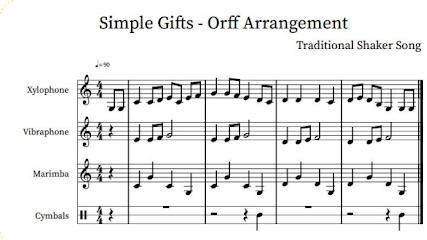

While Orff-Schulwerk teaching most often is centered in younger general music classrooms, there are elements of the Orff compositional process that transfer beautifully to the large ensemble. The bordun (bass), harmony, and color part are digestible compositional elements that students can play with. The bordun is usually a repeating pattern of I and V, adapting to the melody with functional harmony. It can be presented in broken, chordal, or arpeggiated style. The harmony in Orff-Schulwerk might be more of an ostinato, moving with stepwise motion. The color part adds texture and color, but is usually sparse and does not serve harmonic function. The below example notates the first four measures of “Simple Gifts” in a common Orff instrument setting.

(AUDIO LINK)

Introducing Theme and Variations concept

• Students play Twinkle Twinkle Little Star (D

Major) • With stand partner, students brainstorm a list of any possible factors that could be varied (i.e. tempo, time signature, key signature, articulations, etc.) • Listen to audio recording of Mozart’s 12

Variations in C Major K. 265 • As a class, we discuss what variation techniques were heard, and students added new ideas to their lists

Introducing Elemental Composition

Class wrote a group variation of Twinkle (teacher inputting on NoteFlight on SmartBoard).

• Discussion of elemental composition: • Melody – What are we doing to vary it? • Functional Harmony (Bass Line) – Where does the melody lead us? • Harmony – What makes it sound good? Bad? • Color Part – Optional for this assignment (some students added percussion) • Important Orff Concept: EVERYONE learns EVERY PART!

Simple Gifts Composition Groups

• Students played through melody of “Simple

Gifts” – notated. • In small groups (approximately quartet instrumentation), they decided which specific element they wanted to vary (choosing 1 maximum) • Over the course of 4 weeks (30 min/week), each group composed and submitted their variation. The whole class played each variation together. • Students performed their compositions at our Winter Concert, and were proud to have their pieces performed next to “REAL composers!”

Students each had their own NoteFlight Learn account that they used for this project. Feel free to get in touch with any questions about classroom technology logistics or NoteFlight!

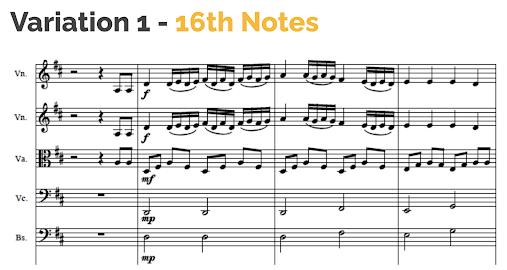

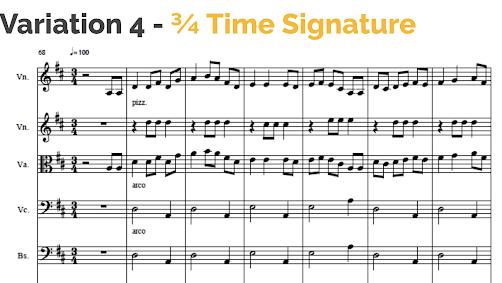

Student Composition Examples

Each group submitted their notated variation, and performed their composition for the class. The class then worked together to choose and combine variations to perform as an orchestra in a concert.

Additional student composition examples, including some more advanced high school composition examples, are linked here.

Student Feedback

“I improved on my collaborative working skills, and I learned that there are many ways to change and modify a simple piece of music. I also learned how to write the different parts of different instruments to accompany each other.” -8th Grade Student

“Going into this project, I had no idea how we would even start to compose a piece of music. I learned that it’s helpful to listen to a melody and change it gradually, then work on bass/harmony lines. I also got better at working with people that I don’t know. -7th

Grade Student

As we hopefully traverse into a more “normal” school year, I would encourage you to explore more composition, even within the large group ensemble setting. Students seem to have a newfound appreciation for being able to once again perform in ensembles, and this spark can be used to help foster creativity as well. I’m happy to connect on this subject or provide more details on composition projects in group settings - touponticelli@pausd.org. Wishing you all a relaxing summer!

References

Allsup, R.E. (2003). Mutual learning and democratic action in instrumental music education. Journal of Research in Music

Education, 51(4), 24-37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3345646 Goodkin, D. (2004). Play, sing and dance: an introduction to Orff

Schulwerk. Schott Music Publishers.

Hogenes, M., van Oers, B., Diekstra, R.F.W., & Sklad, M. (2016).

The effects of music composition as a classroom activity on engagement in music education and academic and music achievement: A quasi-experimental study. International

Journal of Music Education, 34(1), 32–48. https://doi. org/10.1177/0255761415584296 Hopkins, M. T. (2013). Factors contributing to teachers’ inclusion of music composition activities in the school orchestra curriculum. String Research Journal, 4(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/194849921300100402 Hopkins, M. T. (2015). Collaborative composing in high school string chamber music ensembles. Journal of

Research in Music Education, 62(4), 405-424. https://doi. org/10.1177/0022429414555135 National Association for Music Education. (2014). Ensemble music standards. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/wp-content/ files/2014/11/2014-Music-Standards-EnsembleStrand.pdf Priest, T. (2006). Self-evaluation, creativity, and musical achievement. Psychology of Music, 34(1), 47–61. https://doi. org/10.1177/0305735606059104 Stringham, D. A. (2016). Creating compositional community in your classroom. Music Educators Journal, 102(3), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432115621953 Wiggins, J. H. (1999). Teacher control and creativity: Carefully designed compositional experiences can foster students’ creative processes and augment teachers’ assessment efforts. Music Educators Journal, 85(5), 30-44. https://doi. org/10.2307/3399545

Friday,April 28, 2023 ~ Weill Hall, Green Music Center Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, CA

The CMEAState Festivalis back!

DATE AND LOCATION The California State Band and Orchestra Festival, Presented by World Projects, will be held on Friday, April 28, 2023, in Weill Hall, Green Music Center, on the campus of Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, CA.

PREREQUISITES Participating groups must have received a Unanimous Superior rating at a CMEA sanctioned festival or have participated in a Comments Only CMEA sanctioned festival during Spring Semester of 2022. CMEA sanctioned festivals include festivals hosted by CMEA Sections, the Southern California School Band and Orchestra Association (SCSBOA), and the Northern California Band Association (NCBA). Participating directors must be members in good standing of CMEA both at the time of application and the festival performance.Applications include a recording of the ensemble performing approximately 15 minutes of music with at least two works that best demonstrate the group’s abilities. All recordings will be uploaded with the online application which was emailed to all members in May and is available on the CMEA website. The due date for the applications was Thursday, June 30, 2022. Directors will be notified of acceptance by September 1, 2023.

SELECTION PROCESS In addition to submitting audio files and copies of qualifying adjudication sheets, the application asks for information about your school size and demographics.The intent of this festival is to showcase outstanding band and orchestra ensembles that represent the diversity of our great state. FUTURE YEARS FESTIVALS The Spring 2024 festival will take place in a world class venue in Southern California, then the festival returns to Weill Hall in Sonoma in Spring 2025.The application for Spring 2024 Festival will be due in June 2023.The application for the 2025 festival will be due in June 2024.

FESTIVAL PERFORMANCE ADJUDICATION Each ensemble participating in the California State Band and Orchestra Festival will receive recorded comments from a panel of three prominent adjudicators and receive a 20-minute in-person clinic with one of the adjudicators immediately following the performance. You must provide three original scores for each piece your ensemble will perform.

AWARDS/HONORS The competitive aspect of this festival is the selection process.All ensembles that have been selected and perform at the festival will receive an “Outstanding Performance” plaque following their performance.

PARTICIPANT FEE The participant fee for 2023 is $475 and is due no later than October 31, 2023.

- John Burn

CMEA State Band & Orchestra Festival

Coordinator

Mint or Mint Tea?

by Ryan Duckworth,

CMEA Mentorship Representative

Greetings, fellow music educators!

My name is Ryan Duckworth, and I will be serving as CMEA’s Mentorship Representative. I just completed my twentieth concert season as the choral director at Bloomington High School in San Bernardino County (Southeastern Section), served as president of the Southeastern Section for four years, and just completed my one year term as immediate past president to support our new leadership team. In these roles, I have seen the hard work needed to develop a mentorship plan, and it will be my privilege and responsibility to take that plan and oversee its implementation over the next year.

In the next few months, I will be receiving formal training from NAfME and planning the CMEA Mentorship program which, once competed, will be shared with each section’s membership representative or president with the intent of reaching those members who might benefit from mentor and mentee services. That’s the beauty of the system our state has created. There is an entire network of support to make sure our efforts are successful.

As I have started to step into this role for CMEA, I have spent a lot of time reflecting on my own experiences, both a mentor and mentee. My first reaction is that the words themselves seem clumsy. I recently interviewed for a mentorship position in my own district and I remember being asked about my past mentor/mentee experiences. My mind immediately thought, “mint or mint tea experiences?” “Mentor” just is not a word we use in a lot of contexts and honestly “mentee” feels even more awkward for lack of use. I have only had a handful of formal “mentor/mentee” relationships, but have had many people that I consider to be my mentors, and several people that I have mentored in different roles. It all makes me wonder about our profession’s relationship with these concepts.

I think for a lot of us, the idea of a mentor carries an almost archetypal quality. If you will forgive my casual obsession with Star Wars, the mentor-type is Yoda: old, wise, distant, and almost mystical. The problem with this view is that very few of us see ourselves in this way. The mentor archetype here is always someone older and wiser than ourselves. But this isn’t a correct view of the mentorship role. The way in which Yoda is truly a mentor is that he is experienced, having known successes as well as failures, and is willing to pass on what he has learned. Many of us may have heard the “10,000-hour rule” which was proposed by Malcom Gladwell in his book “Outliers.” It basically states that it takes thousands of hours, or approximately ten years of deliberate practice, to become an expert in any field. While this is a major generalization, and

many skills take more or less time to learn, the point remains valid: You have expertise to offer people less experienced than you much earlier in your career than you might think.

The perception of the word “mentee” is even more problematic. We erroneously equate being a mentee with inadequacies. I think this view pervades all of America’s education system and is not unique to the field of music education. Regardless, it is a dangerous perception because it further isolates us in an already isolated profession. As new teachers, or teachers in new circumstances, we are often so scared of appearing inadequate that we resist ever asking for help, relying instead on our “rugged independence” to get us through those first few years. Then, once we have a few years under our belt, we want to maintain an illusion that we “have it all together,” so we compensate (sometimes unhealthfully) and struggle in silence. When you step back from the personal experience and see this with professional distance, it is obvious that these perceptions and behaviors are antithetical to building a true community of learning that we ultimately hope to build.

So maybe it is time we reevaluate our relationship with the “mint or mint tea” (mentor/mentee) dynamic. Music is inherently a field that longs for connection: between the performer and the audience; between the conductor and the ensemble; between the sections of an orchestra, band, or choir; between the teacher and the student. Music is rarely, if ever, isolated. So why do we teach so often in isolation?

This has been true of my own professional journey. I had been in the classroom, as both an itinerant elementary band teacher and a high school choir teacher, for several years before I connected with other music teachers, first through a county music educator association and later through the CMEA. But for me, making this connection was the missing piece in my professional soul—I needed connection to other teachers.

Connection is tied to vulnerability. If you are not familiar with the research and writings of Brené Brown, I would highly recommend taking a look. She has helped me put a vocabulary to many of the issues and ideas I find myself facing as I reflectively grow as an educator. In her book, “Dare to Lead,” she relates a finding in the Harvard Business Review that employees were experiencing high levels of exhaustion not due to the tempo or rigor of the work they were doing, but because of feeling lonely. Loneliness was literally manifesting itself as people feeling exhausted. If this is true, then this need to build connections is more than just a pedagogical tool, it is integrated into our own professional mental health.

So how do we intentionally build meaningful professional connections? I would propose that each one of us needs to purposefully nurture at least three specific professional relationships. • 1st - find someone further along in their career than us; someone who has likely already been through some of the things we’re facing and can offer us advice on what to do and what to avoid. • 2nd - find someone less experienced than ourselves for whom we can give advice and guidance and be a supporter. • 3rd - find someone who is in roughly the same place professionally as you; someone with whom you can commiserate, share, and collaborate on equal terms.

I specifically avoided the words “younger” and “older” because age and experience are not synonymous. Plus it is very likely that different aspects of your professional practice are at different levels of experience. You are never too old to learn something new (be a mentee). You are never too young to share what you have learned (be a mentor). And no matter your age, you need someone with whom you can share the journey, laugh at the struggles, and support each other through shared experiences.

I look forward to working with and learning from all of you in the years ahead. I will be reaching out to the section presidents to learn and connect as we develop and implement our mentorship plans. If you have questions about or insights into this process, please feel free to reach out to me at DuckworthMusic@gmail. com. Let’s work together to create a supportive network of music educators.