13 minute read

Terrior-Struck

TERROIR STRUCK

It's all about the land of course, terra (or should that be terroir) firma, and its relationship with and influence upon those things produced on it and from it. And, as with so many things-epicurean, the French have come up with a suitable mot juste. In his latest article, malt-meister, Chris Goodrum from Gauntleys, looks into the intimate symbiosis between the spirit and the soil, as he attempts to pin down the elusive distillery character of Scottish whiskies. So, buckle up and brace yourself for…The Terroir!

Advertisement

Here's a question for you. What does the whisky in your glass smell/ taste of? Is it rich and fruity? Maybe it's barley-dominated, possibly very citric or minerally, or perhaps it's quite earthy or heavily influenced by peat. It's possible that there's some oak character, whether that's vanillery American oak or fruitcakey sherry, either way it will more often than not be a magical amalgamation of characteristics that we tend to call 'distillery character'. For years both I and many other whisky reviewers have gone on about this concept to the point in which it has become the buzzword of the whisky industry. It is for me, one of the most intriguing aspects of whisky - a magical combination of aromas and flavours that are derived firstly from the barley and augmented by the fermentation and distilling techniques used by each individual distillery. In essence it's what makes the spirit produced at Laphroaig, for example, very different to the spirit produced at Balblair and so on.

However, these days there's a new buzzword doing the rounds, and that is terroir. For most wine drinkers this terroir concept is nothing new - in fact, major regional classifications of European vineyards have been largely based on this concept. So, what exactly is terroir? There isn't an exact English equivalent for this quintessential French term and concept; however, simply put it is a holistic combination of the soil in which the vines are grown, along with the local topography and the influence of both meso and microclimates. The way that each of these elements interact with each other gives rise to this concept and underlies the reason why wines made from grapes grown in adjacent vineyards can taste dramatically different to each other. Without getting overly technical, certain grape varieties, such as Pinot Noir and Riesling are extremely adept at channelling terroir, but what has this all got to do with whisky? One man was responsible for this new buzzword - Mark Reynier. Many of you will know Mark from his days at Bruichladdich and some will know him for his forthright and outspoken views on social media. Mark's first obsession was to finish pretty much all Bruichladdich's spirit in ex-wine casks, (I'm not going to get into that here as that discussion would take up an entire article on its own!), but once he had got that out of his system, his next preoccupation was soil, or terroir, to be exact.

Mark was convinced that barley grown in different parts of Scotland, on different soils and affected by different climactic conditions would have a distinct effect on the character of the finished whisky, and he set out to prove that theory. To be honest I was somewhat sceptical about this claim. Obviously, I was a believer in the concept of terroir as far as wine production went, but I believed that any trace elements of terroir would be lost in the intensive production methods of making whisky. This scepticism was challenged by Bruichladdich's head distiller Adam Hannet in 2016, when he kindly sent me three new-make samples from the distillery's regional barley trials. The first sample was of Concerto barley from farms located in Turniff (East Aberdeenshire), the second was made from the same variety of barley grown on farms in Rainsfield (South Lothian) and the final sample was, again the same barley, but harvested from farms in the Black Isle, near to Inverness.

The Aberdeenshire sample was classic Bruichladdich new-make with signature notes of hyacinth, acacia and honeysuckle. The South Lothian sample was a lot less oily than the Aberdeenshire new-make with an almost starchy character. The barley notes were sweeter, and a lot more pronounced. There wasn't as much heavy, oily feintiness and there were also fewer floral notes as well. Finally, the sample from the Black Isle displayed even sweeter barley notes than either of the other two regional new-makes. I also concluded that it was overall, less expressive. One could argue that it didn't have a lot going for it bar a bit of barley and a little floral note on the finish. It certainly didn't appear to have the strength of character that the Lothian newmake had, and I deduced that it would probably be easily swamped by first fill oak. So, you're probably thinking that I was converted to this whole terroir business in whisky - well, yes and no. There was absolutely no denying that all three of these samples were very different to each other and given that the variety of barley and production methods were exactly the same, there appeared to be enough evidence to support Mark's and Adam's supposition. But go back to the last sentence of the preceding paragraph - yes, that's right, there was one thing missing here and that was oak. Again, I wondered how much of this terroir character would remain after prolonged maturation in oak. Obviously, I was going to have to wait some years before that question could be answered.

That wait was not as long as I was expecting, because prior to Adam sending me these samples, Mark had sold Bruichladdich to Remy Cointreau and had established his own distillery/ laboratory at Waterford on the south-east coast of Ireland. Here, unfettered, he could continue his experimentation, but on a much larger and grander scale. Even if you are not signed up to Mark's vision, you can only marvel at the lengths he has gone to in this experiment. Firstly, he signed up around 100 Irish farms, including organic and biodynamic farms, which grow 12 varieties of barley on 19 distinct soil types, and has created a state-of-the-art logistics system which keeps track of each farmer's harvest. Not only are these stored separately, but he malts and distils each farmer's harvest individually and documents every minute detail of the terroir, harvest, fermentation, distillation and casks that are used.

Distilling at Waterford began in January 2016, but it was around a year later that I had the opportunity to taste a couple of new-make samples. Both samples were made from a variety of barley called Taberna, the first grown by Tom Fennelly on the Cloncassan farm (fine loamy drift soil) and the other grown by David Walsh Kemmis on the Ballykilcavan farm (grey brown podzolics/alluvium soil). Once again there was a distinct difference between the two samples. The Cloncassan farm sample was lightly oiled and displayed a pleasant, sweet barley character, which was the most dominant character, although there was a light earthiness present. When diluted, an almost violety floral note appeared along with some subtle citric notes. The new-make sample from the Ballykilcavan farm was a completely different animal. It was pungent and earthy with an overriding soil character. There was a subtle barley character and more 'whisky-like' fruit notes as well. It was also more complex, and when diluted I could pick out notes of tobacco and waxy spice. A further two samples of new-make spirit came my way in October last year that were distilled from Olympus barley, which like the previous samples the barley came from different farms. The first sample came from barley grown on the fine loamy soil of Timogue farm and the second from barley grown on the shale soil of Tinnishrule farm.

The Timogue farm sample was warm, oily and rich with an almost vanilla accented barley character, and seemed to me that there were definite similarities between this and the Cloncassan farm sample, and I wondered if loamy soils amplified this pure barley character. As expected, the Tinnishrule Farm sample was completely different. It was angular, fresh, sharp and stony with a slightly ascetic, agave-like pulped white fruit. The palate was very lemony and stony with an almost icy fresh austerity; it also felt less evolved than the Timogue farm sample.

So, once again I was left in no doubt that the individual terroir of these farms had a clear impact on the character of the new-make spirit, but there was still an itch that needed scratching for me, and that was oak. Given that Mark's first obsession was ex-wine casks, it was a sure-fire bet that he was going to use them to mature the Waterford spirit in. In fact, he was planning to use not only ex-Vin du Natural wine casks but premium French oak casks, first fill American oak and virgin American oak casks as well. Now, that's a serious amount of oak, and I wondered how the Waterford spirit would stand up to a hammering from such a large amount of oak, including new oak and ex-wine casks. The question was, would there be any spirit character, let alone terroir character left after all that oak had imparted its imprint? Thankfully it wouldn't take too long to find that out, as the distillery kindly sent two pre-release samples of what they were calling their 'Single Farm Origins' range along with the new make samples. Those samples were the Sheestown 1.2, distilled from Irina barley, harvested in 2015 and grown by Phil O'Brien in Kilkenny, and the Ballymorgan 1.2, distilled from the Overture barley variety and grown by Robert Milne in Wexford. So, with baited breath I poured the samples into my nosing glass… The Sheestown 1.2 was indeed quite oaky. The American oak casks had imparted a fair amount of vanilla, the French oak had added a good dollop of taught tannin and there was, of course, a slight winey note as well. There was a lovely, fleshy, fruity spirit character and a distinct minerality on the palate. The combination of the 50% abv and the developing citrus notes left the finish a little on the austere side, but it appeared that the spirit had handled the oak pretty well. The Ballymorgan 1.2 was, considerably less influenced by the oak. That's not to say there wasn't any - there were hints of vanilla and tight wood spice, but it wasn't overwhelming the spirit and terroir character. It was about 600 days younger than the Sheestown 1.2 and that youthfulness was noticeable, but I got a distinct earthiness and pronounced minerality on the palate. Like the Sheestown 1.2, the finish was a bit on the austere side, but it had a lovely progression to it. If this were my project, I would probably have opted to just use refill American oak, because that way the oak imprint would have been minimal and a lot more of the spirit and terroir character would have been evident. But would that have made for an enjoyable drinking experience? It could certainly be said that the use of the different cask types had added an extra dimension to the finished Waterford whiskey, which is what you would hope for, and my fears about all the spirit and terroir character being lost under a mountain of oak were definitely put to bed. I concluded that not only is Mark right in his belief that terroir affects the character of the finished spirit, but that it can still be detected after a period of maturation in oak. Now, whether those characteristics will still be evident when the spirit is a lot older, I just couldn't say and obviously only time will tell, but for now I can say - I am a believer! Here are some choice whiskies with their own distinct character to try now:

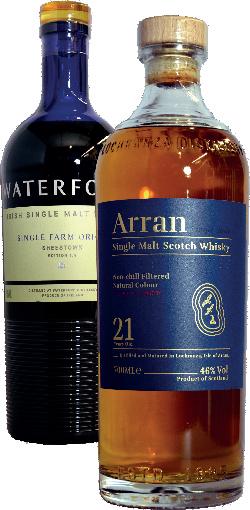

Waterford Single Farm Origin - Sheestown 1.2 50% £69.95

Btl: Sept 2020 (aged 4 years & 9 days). 33% American oak, 19% New American oak, 25% French oak, 23% Vin du Natural casks The nose is a little fresher and showing more barley character than the pre-release sample. The creamy American oak is subtler with just a touch of toffee. Quite citric and stony with lemon, botanical spirit, soil, bran flakes and late fortified wine notes. The palate shows subtler creamy oak and French oak tannins making the spirit character more apparent. Long if a little austere with lingering mineral and citrus. Subtle soil, cereal, fortified white fruit, sweet spice and cereal in the finish.

Arran 21-year-old 46% £126.95

First & refill Sherry hogsheads. Btl: 2019 A lovely aromatic nose of mature apricot, pineapple and some gentle, spicy sherried dried fruit. Hints of toasted oak, almond and juicy, sub-tropical fruit follow. The aromas are predominantly refill sherry-orientated that it is beautifully balanced with late white chocolate and lime conserve.

The palate opens with some soft and mature oak vanillin and slightly coffee'd Oloroso. Hints of raisins and prune give the fruit a darker character, but there's still mature tropical fruit notes. Long, citric and very salty with returning vanilla, pepper and dried fruit. Like the nose the balance is superb.

Bruichladdich Port Charlotte MRC:01 2010 (7-year-old) 59.2% £88.95

50% First Fill American oak/ 50% Second Fill French Red Wine. Btl: 2018.

A lovely mellow and woody nose with a distinct French oak grainy tannic character. Hints of vanilla, medicinal peat, red fruit, leather, earth and dry peat smoke emerge. With time a smidge of coconut, black pepper and dark chocolate. The palate is soft and mellow, with dried redcurrant/ cherry, earth, medicinal peat and like the nose a distinct grainy French oak character. The alcohol although quite high is impeccably contained by the weight of the spirit. Very complex and mouth-filling with treacle, tar, dark chocolate, dry peat and gritty peat smoke. Long and medicinal with lingering menthol, bog myrtle and tar. Water makes the nose slightly oilier and waxy. It's less woody with more emphasis on the dried fruit. Subtler peat notes as well. It also emphasises the dried red fruit and earth on the palate. Still quite medicinal and sinus cleansing but the peat is drier and dustier.

Starward Two-Fold 40% £34.95

Wheat spirit and barley spirit aged separately in Australian red wine cask.

A dense fruity and tropical nose - apricot, pineapple, barley and hints of pepper, winey red fruit and vanilla. Aromatic and Mackmyra-esque with late red sherry and subtle mentholated herbal notes. The palate opens with oft red fruit conserve and hints of barley. Less tropical than the nose suggests but there is still a good depth of fruit. Noticeable red cherry and tannin on the middle along with a light creaminess. Long and spicy with notes of tobacco, red wine, barley, spice and liquorice in the finish.

Stauning Triple Malt Kaos 46% £64.95

A blend of single malt, malted rye and peated malt - bourbon matured A definitely interesting nose! Opens with youthful rye and chunky barley with hints of apple, red berries, red grape and smoky, oily peaty spices. Slightly earthy with a touch of chocolate powder. The palate also opens with the oily rye. Not quite as full as the nose suggests but there's a good depth of sweet apple, roasted malt, cereal, hazelnut and astringent, oily peat. Subtle American oak notes on the middle. Long, oily, peaty, rye finish with grippy, peppery spice and subtle dried fruit.