6 minute read

TITLE IX PIONEERS

50 years of promoting equity in women’s athletics

by Cindy Dashnaw Jackson

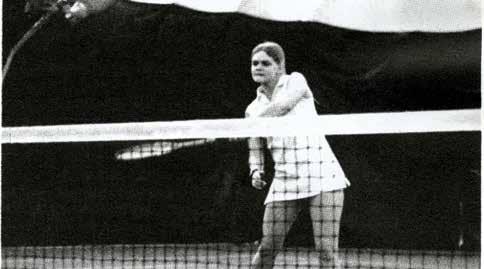

The words “played Butler men’s varsity tennis” aren’t a mistake on the resume of Suzanne (Yerdon) Lewandowski ’76. The former top high school player had no other choice: Butler University didn’t have a women’s tennis team yet.

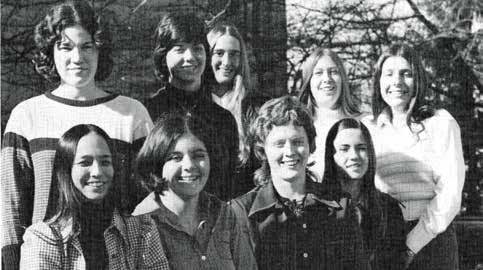

Mary Jo (Vidal) DeWolf ’75 played every women’s sport Butler offered: basketball, volleyball, and field hockey. Players shared uniforms, had no locker rooms, brought equipment from home, and provided their own transportation.

Judy Horst ’62 says, “We had no women’s golf team. I was it.” And Barbara (Rice) Greenburg ’64 faced the limits placed on women as both a Butler player and coach.

“The [men’s and women’s] coaches’ responsibilities were so unequal,” Greenburg says. “As a coach, I made the schedule, I made all the travel arrangements, and I got the officials to the game—no one ever assigned officials to any of my games.”

Today, thanks to a landmark federal law called Title IX* , women’s sports have come much closer to matching those of men. Butler offers nearly a dozen with dedicated budgets, facilities, equipment, and coaches, and women athletes are regularly awarded letters and inducted into the Butler Athletic Hall of Fame.

To mark the law’s 50th anniversary and honor those fighting for equity in athletics, Butler Magazine talked to these athletes about how the law affected their college sports experience.

Adjusting to Title IX

Lewandowski had intended only to practice with the men’s tennis team but thinks she remembers the coach asking her to compete.

“I just went with the flow. It was fun riding to meets in the van with the guys,” she says. “After an article about me came out in The Butler Collegian, I had my 15 minutes of fame, but there really wasn’t much fanfare.”

‘Riding to meets in the van’ was a novelty for female athletes before Title IX. In fact, “I always wanted to coach long enough to go with my team on a commercial vehicle, but I never made it,” Greenburg says. When she finally got a team vehicle, “It had been a hearse. We named it the Blue Goose. We were finally traveling together, and that added to our spunk!”

The Blue Goose didn’t make things equal, though. When an axle broke, the team had to sit until Greenburg’s husband could get there with his station wagon. In another incident, they’d pulled off the road with a flat tire; a vehicle filled with male Butler players slowed down—and then passed on by.

“We found out later they’d said, ‘Let the [derogatory term] change their own tire,’” Greenburg says. “We got an apology. And had a discussion about Title IX.”

The year without Butler women’s sports

Then came the year that the Butler women boycotted sports.

“The other coaches and I decided we wouldn’t coach anymore because we were getting almost no money and had full teaching loads. So when teams from other schools came to Butler, we wouldn’t play them,” Greenburg says.

It was DeWolf’s senior year, 1974–1975.

“We thought we were headed to field hockey practice one day and instead found out the women’s coaches were talking about not playing,” she says. “Butler hadn’t started to come into compliance with Title IX yet, and they thought the only way we could make an impact was to cancel all women’s games that year.”

The players agreed, electing DeWolf to be their spokesperson. Instead of being angry, visiting teams’ players and coaches supported Butler.

“We were absolutely right in saying ‘this is wrong,’” Greenburg says. “It was a big deal because other schools got involved. So they changed it.”

Greenburg credits Xandra Hamilton ’58, MS ’60, the women’s Athletic Director, for moving Butler in the right direction.

“Xandra did more to get things for girls than anyone. She wanted girls to play on the big floor for basketball and volleyball. She was a fighter for women and the things that got changed.”

Women’s sports move toward parity Change took time. When Greenburg retired in 1994, her softball recruiting budget was still just $300, and she was the last person at Butler to both teach PE and coach full-time. Four years later, Greenburg became one of the first three women inducted into the Butler Athletic Hall of Fame, receiving a Special Service Award for 30 years of coaching. Sisters Barbara Skinner ’82 and Elizabeth “Liz” Skinner Spencer ’82 were the other two inductees. Women like DeWolf have begun receiving the varsity letters they’d earned so long ago.

“It’s wonderful what Title IX has brought to women’s sport and young girls,” Lewandowski says. “Hard work in grade school and high school can be rewarded with scholarships and sponsorships. What was once impossible is now possible!”

DeWolf had a full-circle moment around the time she received her letter.

“A student in the high school class I teach had received a Butler basketball scholarship. She was being honored at a game in her senior year, so I went. They had cheerleaders! They had the band playing at a girls’ game! They had a crowd, and I started crying. My thought was, ‘Oh my, it was worth it. We changed so much for them.”

By Emily Schlorf ’21

Over his 16 years at Butler, Head Coach of Track and Field and Cross Country Matt Roe has been integral to Butler’s success—namely by leading his teams to 106 conference individual and relay titles, 68 school records in track and field, producing 39 All Americans, and capturing 14 conference team titles. He’s been named Conference Coach of the Year 13 times and was a finalist for Women’s Division 1 National Coach of the Year in 2013.

Achieving these accolades is anything but easy—especially when competing against other Division 1 schools sprinting toward the same goals. To Roe, it’s a lot like climbing Mount Everest.

“We’re trying to constantly climb that mountain; but if we stay at it, we get to this higher elevation, we adapt to that elevation, and we leverage that adaptation to be able to climb higher,” Roe says. “What we’re trying to do is stay as high up on the mountain as possible and have that be our normal.”

Roe sees Division 1 schools as existing on a spectrum. On one end are elite (and often rigorous) academic institutions, and on the other end, “sports factories,” or schools with ultra-intense athletics. Butler is somewhere in the middle, which allows Roe’s runners to be both students and athletes.

“We’re really elite on the athletic side [but] you can do it all here … An unseen part of our success is our ability to balance both,” Roe says. “That’s one of the things I love most about coaching at Butler, that we’re getting engaged, intelligent, driven people who can go anywhere from Butler without any of the residual challenges that you’d have on both sides of the bell curve. That’s really the secret sauce.”

That sauce is something special. Semester after semester, the track and field and cross country teams are recognized for having some of the highest (and often the best) GPAs out of all Butler athletic programs. Nationally, Butler’s track and field’s combined GPAs were 10th highest and cross country’s eighth last year.

Another ingredient in that recipe is Butler’s uncommon combination of Division 1 athletics and a small student population. A school where you’re not just a face in the crowd is especially comforting to the handful of Roe’s athletes who come from other countries.

“One of my goals is that when [international students] come here, when they’re done, they’re running at the elite level internationally,” Roe says. “From there, that’s usually the point where they say, ‘okay that’s what I’m looking for,’ and we’ll say ‘and by the way, the faculty-to-student ratio is 11:1, there’s a 99 percent placement rate,’ and all the things that come into that make them feel more comfortable about choosing Butler.”

When scouting for the next perfect addition to the team, whether from near or far, Roe knows he has to hone in on what makes Butler special, especially when competing against those elite schools.

“We lead with ‘This is where we’re going to help you as a person, and this is where we’re going to guide you along the way,” Roe says. “It’s still going to be difficult, … but what about an environment where everyone’s rooting for you and trying to help you get there?”

Perhaps it’s this mindset that’s to thank for the teams’ success on and off the field. By teaching his runners the value of working through the pain to become stronger, he sets them up for success in the future. And coming from what he describes as a service-driven family, this is where Roe’s North Star shines brightest.

“The satisfaction that comes from facing something really difficult cannot be understated… there’s such an empowerment to that,” Roe says. “That’s my service. I try to use running and competition as a metaphor and opportunity for people to look and become stronger inward so that they can be stronger outward.”