17 minute read

Quebec Softwood Shipments

accepts preservative treatment well.

Reportedly, it has shown up recently in Southern U.S. markets as both fence boards and radius edge decking. While it is difficult to determine the exact volumes of specific products, radiata continues to gain wider acceptance.

Southem pine wood (e.g., loblolly, slash) grown in Brazil is another pine substitute used in the U.S. Some users say it has properties quite different from timber grown domestically. Much of it is coming in the form of fingerjoint blocks for manufacturing into fingerjointed mouldings and related products.

Another supply source for the U.S. market is Mexican pine, a species that is very similar to ponderosa. To date, most of this material has come to the U.S. in lumber form, although some shipments of logs have also been made. There reportedly have been some concerns about the quality and consistency of Mexican pine.

supply problems for U.S. users who need this wood, usually for industrial purposes, shipping and crating.

Another issue is emerging public policies. Following a B.C. precedent, New Brunswick has adopted what I call "blackmail value-added" policies, under which users of Crown timber will be penalized if they do not increase value-added production. To the extent that such policies are effective, they will import value-added jobs from the U.S., and further curtail supplies of lower grade softwood to U.S. users.

Political debate continues in Quebec over the issue of separation from Canada. Candidates supporting separation are popular, and the issue is regularly in the news. So many uncertainties are involved in this issue that it seems that the lumber industry is simply focusing on getting business done and not worrying overmuch about the politics.

South bf the Border

By Bill L. Mitchell The Beck Group

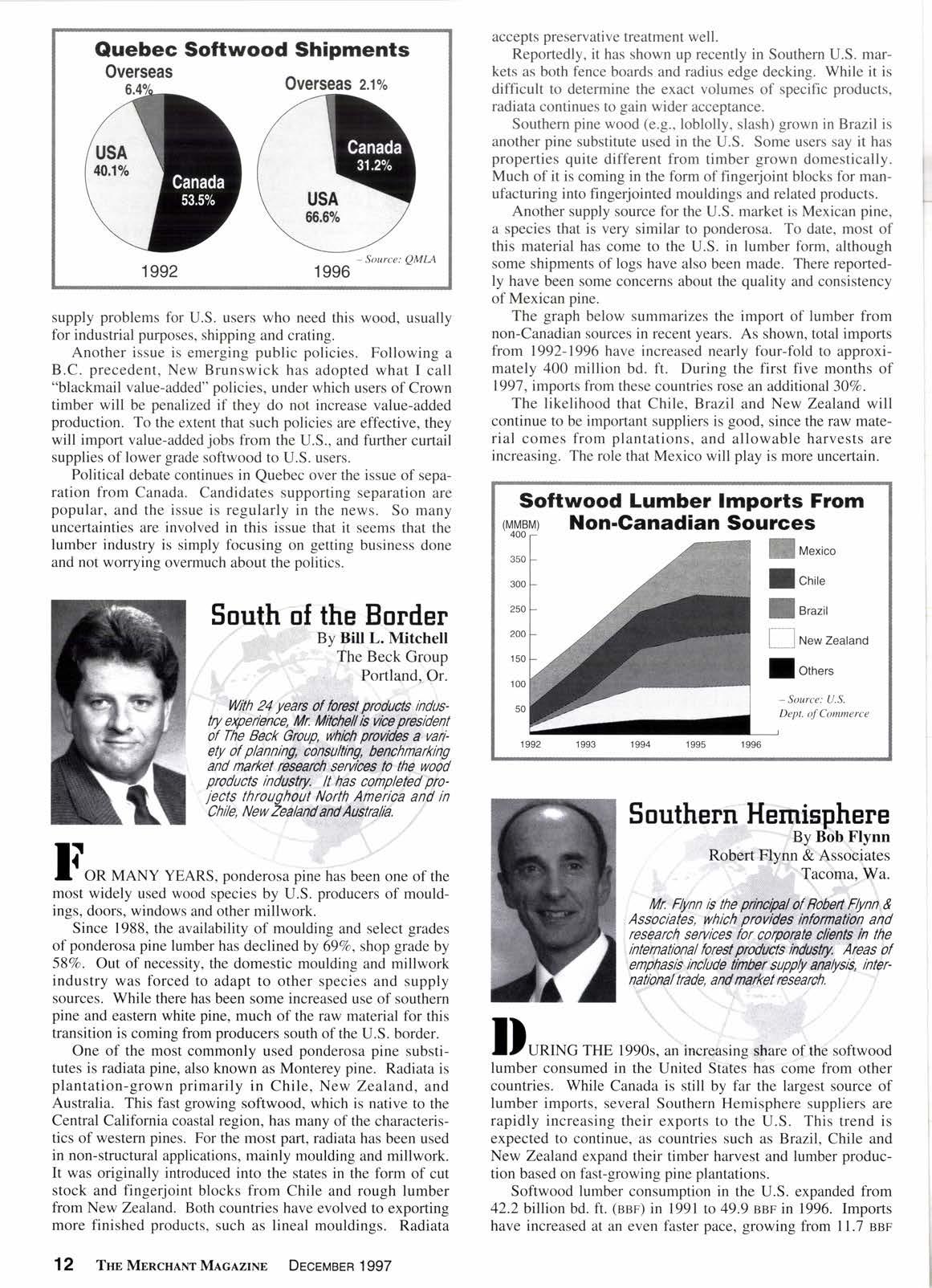

The graph below summarizes the import of lumber from non-Canadian sources in recent years. As shown, total imports from 1992-1996 have increased nearly four-fold to approximately 400 million bd. ft. During the first five months of 1997, imports from these countries rose an additional30Vo.

The likelihood that Chile, Brazil and New Zealand will continue to be important suppliers is good, since the raw material comes from plantations, and allowable harvests are increasing. The role that Mexico will play is more uncertain.

Softwood Lumber lmports From (MMBM) Non.Ganadian sources

uatiproducts ind6ttN. iects throuohout I 'Chr/e, NewZealand,

Southern I

FOR MANY YEARS, ponderosa pine has been one of the most widely used wood species by U.S. producers of mouldings, doors, windows and other millwork.

Since 1988, the availability of moulding and select grades of ponderosa pine lumber has declined by 697o, shop grade by 58Vo. Out of necessity, the domestic moulding and millwork industry was forced to adapt to other species and supply sources. While there has been some increased use of southern pine and eastem white pine, much of the raw material for this transition is coming from producers south of the U.S. border.

One of the most commonly used ponderosa pine substitutes is radiata pine, also known as Monterey pine. Radiata is plantation-grown primarily in Chile, New Zealand, and Australia. This fast growing softwood, which is native to the Central California coastal region, has many of the characteristics of western pines. For the most part, radiata has been used in non-structural applications, mainly moulding and millwork. It was originally introduced into the states in the form of cut stock and fingerjoint blocks from Chile and rough lumber from New Zealand. Both countries have evolved to exporting more finished products, such as lineal mouldings. Radiata

Ilti

ITURING THE 1990s. an increasing share of the softwood lumber consumed in the United States has come from other countries. While Canada is still by far the largest source of lumber imports, several Southern Hemisphere suppliers are rapidly increasing their exports to the U.S. This trend is expected to continue, as countries such as Brazil, Chile and New Zealand expand their timber harvest and lumber production based on fast-growing pine plantations.

Softwood lumber consumption in the U.S. expanded from 42.2blllion bd. ft. (snr) in l99l to 49.9 ssp in 1996. Imports have increased at an even faster pace, growing from ll.7 nnn in 1991 to 18.2 ssr in 1996. In 1996, imports accounted for a record 36.5Vo of softwood lumber consumption in the U.S.

Most of the lumber imported into the U.S. comes from Canada. In 1996, Canadian lumber made up 97.lVo of all softwood lumber imports, down from 99.2Vo in 1991. Although the total volume of lumber imported from countries other than Canada is still small, the fastest growing sources for lumber imports have been Brazil, Chile and New Zealand. Mexico has also increased its softwood lumber exports to the U.S., although an unknown portion of that volume (total = 123 MMBF in 1996) is re-export of U.S. lumber which goes into Mexico for remanufacturing.

The pine lumber coming in from New Zealand and Chile is radiata pine, and the pine from Brazil (and more recently Argentina) is primarily loblolly and slash pine. A market has been created in the U.S. for this lumber as a replacement for ponderosa pine lumber, production of which has declined sharply during the 1990s. Since 1989, production of ponderosa pine lumber has fallen by 43.7Vo, or almost 1.8 ssr. More important, production of better quality ponderosa lumber has declined even faster: shop grade production declined 56Vo from 1989 to 1996, while production ofselects fellby 66Vo.

Better quality ponderosa lumber has long been a mainstay of the U.S. moulding and millwork industry. When production of ponderosa pine lumber began declining (due primarily to cutbacks in timber harvested from National Forests), the industry had to find another source of similar quality material. Fortunately, radiata pine and southern yellow pine from fastgrowing, man-made plantations were suitable replacements.

Most of the forest plantations in the Southern Hemisphere were established with the help of government subsidies or tax breaks, to encourage tree planting on poorer agricultural lands. Because these forests are all man-made, on lands which had, for the most part, been cleared for agriculture, the environmental controversy surrounding logging of "old-growth" forests does not exist. The large pine lumber producers in these Southem Hemisphere countries can truly claim to be producing lumber from "sustainably managed forests."

Imports of softwood lumber from Chile, New Zealand and Brazil have increased almost ten-fold during the 1990s, from 35 vt'rnr in 1991 to an estimated 330 t'ttrlnr in 1997. Imports of softwood moulding and dowels have increased at an even faster rate, from about 29 million lineal ft. in l99l to an estimated 612 million lineal ft. in 1997. Of the three countries, Brazil is the largest supplier of lumber to the U.S., while Chile is the dominant supplier of moulding and dowel imports.

Will this trend continue? There is really no possibility that production of ponderosa pine lumber will return to the levels of the early 1990s; in fact, it is doubtful that production can be increased above 1996 levels, because of restricted timber supply from National Forests.

Meanwhile, the supply of radiata pine in New Zealand and Chile is expected to continue increasing-the total harvest in the two countries will almost double by the year 2010.

Radiata producers are taking a number of different approaches to the U.S. market. Fletcher Challenge of New T.rualand has been focusing on the solid pine moulding market in the U.S., and intends to greatly expand its share of that market, based on its large supply of pruned radiata pine timber. In contrast, most Chilean companies are focusing more on the fingerjoint moulding market, where they have already been quite successful. We expect both New Zealand and Chile to continue expanding exports to the U.S., although they do face stiff competition from other sources.

Brazilian pine has become quite popular in the U.S. millwork industry, and U.S. imports of Brazilian moulding have increased from 9 million lineal ft. in 1994 to 132 million in 1997, a l,366%o increase in just three years! However, the pine timber harvest in Brazil will be limited, due to a low rate of planting in Brazil since the financial incentives ended in 1986. In fact, some experts have forecast that a shortage of pine timber in Brazil will emerge in another l0 years, due to limited supplies and growing domestic demand.

Pine imports from the Southem Hemisphere also face competition from sources closer to home, such as Eastern white pine. In addition, there has been a renewal ofinterest in southem yellow pine from the U.S. South for millwork production. Finally, surplus softwood from other sources, such as Scandinavia and the former U.S.S.R. countries, will also compete in the U.S. (Some companies have already begun importing shop and moulding grade lumber from the Baltic countries, which competes directly with radiata pine.)

In summary, we expect imports of lumber and moulding from Southern Hemisphere pine plantations to increase in the future, but at a slower rate than that experienced in the 1990s.

These imports will help to keep prices down for industrial grade lumber, but will have almost zero impact on structural lumber markets. There really is no good, inexpensive altemative to domestic (and Canadian) sources of structural lumber, and the building industry in the U.S. must remember that in the ongoing debate over timber harvesting in North America.

=-'8ussia forest products output has recently slowed. The direction which production, consumption, and trade of forest products will follow in the near term will be shaped by the new economic conditions which remain unclear but which will differ significantly from the prior centrally-planned economy. meters (mr) in 1988, but declined to ll0 million in 1996. A further 87o decline in the first halfof 1997 should resulr in a harvest of about 85 million mr for the year, including 68 million ofconifer timber. The northern European region is facing continued overcutting of conifers by as much as l-ll2 to 2 times sustainable levels since the lack of roadbuilding invesr ments has forced heavy cutting in already accessible forests.

Policies affecting Russia during the transition to a market economy have drastically altered production, consumption and trade. Western Russia is the center of population and production-including forest products-with relatively well developed infrastructure and markets, yet more heavily exploited forests. The eastern region, including the Far East and East Siberia, is characterized by extensive undeveloped forests, relatively low population, lack of infrastructure and transportation, and low levels of industrialization for the forestry sector.

Declines in the forest sector, first evident in 1990, continued largely unabated into 1997, affecting both production and export trade. The sector has been plagued by deteriorating infrastructure, high interest rates, lack of credit, shortage of capital for investment, obsolete equipment, lack of marketing knowledge (especially export markets), tax and license issues, and steeply rising energy, rail and transportation costs' Despite higher prices for products, the forestry sector has increasingly found operations unprofitable. In 1996, about half of wood industry enterprises were unprofitable due to unclear property rights for forests and timber, requirements for prepayment for supplies and materials, and other constraints.

Total roundwood harvest of all types was 354 million cu.

Lumber production has also suffered substantial declines since the imposition of reforms. Russia produced 104.8 million m3 of lumberin 1988, but only 35.7 million in 1995 and 2l million in 1996. With the declines, European production rose proportionately to about three-quarters of the Russian total, up from one-third in 1989; simultaneously Eastern Russia production slipped further to one-fourth of the total despite having the dominant share of timber resources. Declining domestic demand and non-competitive product quality has shifted the emphasis in the East towards unprocessed log exports while in European Russia declining domestic consumption has encouraged greater lumber exports. While total lumber production declined 66Vo from 1988-1995, exports actually increased from 8.2 million m:r to 9.2 million.

The Russian federation recognizes the critical n€€.d to restructure the forest products industry in the wake of the serious difficulties experienced since 1991, but rcforms have met with only limited success ro dare. Economic difficulties ad political uncenainty have discouraged all but the most adventurous investors and limited bilateral government support.

Past forest use was not constrained by today's economic realities. and land use and harvests were centrally planned without due consideration of economic feasibility. After all, Russia had 25Vo of global forests. Siberia alone held about 207o. including 527a of conifer and l37o of deciduous foresls. Its forests yield an annual net growth of I billion m'. Timber, il was presumed. wasn't a serious constraint to developmentso long as economics didn't really matter. E@nomic refgrrp8" land use,and environmental concerns have ckaaged this view and will dramatically affect the future of this sector.

While the 771 million hecrares of Russian forests soritain an estimated 82 billion m3 of growing stock, only 55 billion mr (67Vo) are accessible. Fully 43Vo of the invenrory in the Far East and 477o in East Siberia (21: billion m3) are inaccessible.

In 1995, total industrial log exports were 18.45 million m3, up from apost-reform low volume of 16.9 million in 1992 and nearing the 18.7 million exported in 1989. Trade in forest products ffom European Russia is primarily composed of lower grade softwood logs (pulpwood), softwood lumber, plywood, and pulp atrd paper products. In contrast, trade from the Asian-Pacific region of Russia is primarily unprocersed conifer sawlog and much smaller volumes of lumber end other processed rnaterial. Trade in industrial sawlogs has been almost entirely to Pacific Rim markets. Lower grade logs to western Europe are also important to European Russia's trade,

From 1965-89, annual lumber exports averaged approxi-:: mately 7.5-8 million mr. Softwood lumber exports were J.j million in 1989. Deciduous lumber exports were much smaller, averaging only 200,000 to 300,000 m3. About half of lumber exports went to western Europe 1U.K., Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, France) with another 2 miUion mi shipped to former Eastern European trade partners. AbodtO.5-l million m3 went to the Mideast (primarily Egypt) and North Africa. Pacific Rim exports were below 200,000 m3 from 1983- l987.

Lumber exports declined to 3.8 million m3 by 1992, recovering to 5.25 million in 1994 and 7.3 million in 1996. pacific softwood lumber exports increased to 425,000 m3 in 1995 (primarily Japan) before slipping to 40,000 mr in 1996. Due to the difficulties faced by the lumber industry in the Far East, exports have shifted to unprocessed logs.

What then of the future role of the Russian forest resources in supplying wood and fiber to global markets? The major components of supply are the principal harvest and harvest from non-forest sector lands, which together accounted for 847o (342 million mr) of total supply in 1989. Other components include intermediate harvesting (29 million), "other" harvesting (23 million), use of secondary fiber (74 million), and imported solid wood raw materiaUpulp products ( I million).

The principal harvest is directly linked to the calculated Annual Allowable Cut (AAC). Although the physical AAC has been frequently estimated to be as much as 833 million m3, the actual harvest reflects the economic reality of both currently and potentially accessible lands. For Russia as a whole, 426 million mr of the AAC (248 million of conifer, 178 million of deciduous timber) is derived from currently accessible forests, 119 million from potentially accessible forests. Realization of the potential AAC depends on the restructuring of the industry and the success of political, economic and market reforms.

Total Russian domestic consumption of wood materials (whidh cornpetes with exports) wai estimated at an annual average of 207 million mr for 1990-1995. The toral annual wood fiber ptoduced amounted to 227 million; exports amounted to an estimated 19 aillion mr annually.

Prejqgtions for 2000 range from 199 million m3 available annually, with 190 million consumed domestically and 9 million exported, to an annual supply of ?25 million m3, with 204 million censumed domestically and 20 million exported, and most opti.mistic, supply of 302 million mr of which 256 million is used domestically and as much as 46 million exported.

Log exports for 1990-95 were estimared at 13 million m3 (6 million higher grade sawlogs, 7 slillion lower grade). The Pacifi c-Asian region pri mari ly exports unprocessed sawtimber rather than pulpwood or processed products. Western Russia's exports, primarily to western European markets, are heavily concenftaled in lower grade logs (5 milhon m''. Russian total exports to 20fi) should remain relatively sraric ar the reduced levels of 13 million achieved in recent years. European estimates for 2000 are 7 million with Pacific exports of 6 million.

Under pessimistic ceoditions, 2000 total log exporrs could fall further to only about 7 million m3, with 2 million ol pulpwood going to western Eumpe and 5 million shipped to the Pacific Rim. The optimistic scenario foresees toral log exports growing to almost 29 miltion mr, wirh Pacific Rim exports ro l2 million mr and European exports reaching l7 million.

Until 2000. average annual total Russian lumber exports should be about 3.3 million m'. falling slightly lrom 1990-95 levels. Under pessimistic conditions. domestic use o[ lumber would drop further. with 5.1 million mr exported (4.9 million from European Russia). The optirqistic scenario sees lumber exports inereasing to 5.7 million rns, with 5.5 million from the West. However, Pacific-Asian,'exports to the Pacific Rim remain at 200,Om mr under all scenarios due to the deteriorating capacity and quality limitations of the existing sawmill sector in East $iberia and the Far East. Estimated exports of wood-based pagels (including plywood) are small ( j00,000 m3) with esserti*lly all panel products from the West.

The forestry sector in Russis has substantial unrealized potential for development. Resources are relatively abundant but utilization is presentl;r limited by lack of affordable timber €rccess. managementand marketing expertise. and investments in appropriate technology. Substantial capital investment. ''including direct foreign investment and joint ventures, is required to transform the existing capacity to standards of technology and product quality to become truly competitive in the international markets of Western Europe and the Pacific Rim. Overall, investments in regional infrastructure will also be required to make the harvesting and processing of timber even at pre-reform levels viable in the near term under more market-oriented criteria of profit and loss.

The export of logs and wood commodities in the near term will remain comparatively attractive as domestic prices adjust to international levels in the face of collapsing domestic markets. Prospects for now until 2000 depend on policies to promote investments, primarily from Western sources, and the reinvestment of hard culrency earnings being generated by the current owners-producers-exporters in the forest sector. The longer term prospect for wood exports remains clouded in political uncertainty. Sustainable economic limits imposed by the forest resource may effectively limit utilization to levels near or below the historic centrally-planned but uneconomic and unsustainable levels. The contribution which Russia can be expected to make in global markets will ultimately reflect economic realities of both uncertain domestic as well as international forest products and markets.

Not Where-What

By Robert L. Berg ReswCe Infmmation Systems Inc. Bedford, Ma.

Mr. Berg is for R/S/,

IZONCERNS over wood products supply took center stage in the first half of the 1990s as dramatic changes in public timber supply policies in the western U.S. and Canada greatly reduced the availability of sawtimber. However, high price levels and volatility for those products derived from sawtimber precipitated a series of market adjustments to capacity, trade and technology that will continue to unfold well into the next century. In the future, the question of what kind of wood products will be consumed will be of equal or more interest than where the wood will come from.

The high prices for lumber and plywood in the first half of the 1990s stimulated investment within these sectors. Investments were directed towards building new capacity or expanding existing capacity in those regions that had access to competitively priced timber. In the lumber industry, from 1990-1997 the capacity base in eastern Canada and the U.S. South increased 3.8 billion bd. ft. (25Vo) and 3.3 blllion (23Vo), respectively. Because of this growth, lumber capacity has regained half the capacity lost in the early 1990s. By 2000, softwood lumber capacity in North America should be back to the levels of the late 1980s. Meanwhile, plywood capacity in the South actually increased 1.5 billion bd. ft. or lZ%o from 1990-1996 to fill some of the void left by the collapse of the plywood industry in the West.

The competitive advantage of low cost altematives to lumber and plywood was greatly improved in the early 1990s and investments in these areas surged in recent years. In the panel sector, the capacity base for OSB doubled from 1990-1997, more than offsetting the lost plywood capacity in the West. And, U.S. and Canadian MDF capacity in 1997 will be nearly double the 1990 level as many users of industrial lumber products (moulding, millwork and fumiture producers) substituted more cost-competitive MDF in many applications. MDF and OSB capacity in North America will continue to expand in 1998-1999, but the rate of growth will slow.

Engineered wood products capacity has also increased in recent years and the investment cycle in these areas is not finished. Wood I-beam, laminated veneer lumber and strand fiber lumber products have grown dramatically through the

1990s and made major inroads into traditional dimension lumber markets. Capacity for engineered wood products continues to expand at this point in the business cycle, and these relatively new products will continue to capture market share.

While the supply response to policy changes in the early 1990s is already quite evident in the product markets, the supply response in timber markets has not been fully realized. Investments in more intensive silvacultural management and the expansion of timber plantations onto marginal farmlands in the U.S. will yield increasing fiber growth well into the next century. These developments are also taking place in non-traditional wood fiber supply regions (South America, Asia) which will show up in products that compete with the North American softwood lumber industry in the offshore markets.

The investment response to the policy-derived shortages of wood products in the early 1990s gave way to increased supply of alternative wood products in the second half of the 1990s. Currently, North American wood products capacity is higher than when we entered the 1990s and this investment cycle has not run its course. Furthermore, the timber policies accelerated the transition from wood products derived from larger, high-value products to products relying on lower-value' faster-growing fiber sources.

High timber costs in the U.S. precipitated a decline in lumber and log exports from the U.S. West Coast. Log exports from the U.S. West Coast dropped more than 50Vo from 3.7 billion bd. ft. (Scribner log scale) in 1988 to 1.5 billion by 1996, free\ng up logs for lumber and plywood production. Lumber production in the U.S. West Coast incteased 4Vo in 1996 and will be up 67o in 1997. Even more revealing, Crown Pacific has plans to build two new stud mills in the U.S. West with a total capacity of close to 200 million bd. ft.

High-cost North American softwood lumber precipitated a decline in exports, forcing countries that previously imported our lumber and timber to find competitive alternatives. The number of alternatives available to them increased and will continue to increase as investments in these offshore markets were also stimulated by high product prices. This will make it difficult for U.S. and Canadian softwood lumber exports to recapture market share in offshore markets. Furthermore, wood products consumption in Japan has suffered a major setback in response to lower housing construction, and the housing market in Japan is expected to remain weak in 1998-'1999. U.S. and Canadian offshore softwood exports have fallen 25Vo from 1989-1996 with the U.S. share falling from 43Vo to 32Vo. Any recovery in offshore demand for North American softwood lumber is expected to be muted in the near term so more timber and lumber will stay in North America.

Finally, technology will add another dimension to the availability of wood products in North America. Through the 1990s, investments in new conversion technology increased product recovery from the high cost timber. The volume of lumber recovered per unit of log input in the U.S. South increased l07o ftom 1990 to 1997, and plywood recovery in the region increased 9Vo over the same period. While to our siders, the wood products industry is a low-tech sunset industry, those following it more closely know that improvements in conversion, resin and new product technology have been fast and furious in the 1980s and 1990s. It would be naive to think that this trend has come to an end. Further gains in resin and conversion technology will result in expanded production and improved product performance without increasing the volume of wood needed.

Wood products markets have undergone dramatic changes in the 1990s, and it serves as a testament to the strength of the supply response of the market. Recent developments mean there will be ample supplies of wood products into the next century, but the composition of that supply will be dramatically different than when we entered the decade.