3 minute read

THE FIRST FLUTTER OF THE BUTTERFLY

BY ALICE MCDOUGALL (RSPB Volunteer)

Surely, a butterfly is one of the most enchanting sights of Spring - that flicker of colour, the delicate quivering wings - and then, in a flash, it’s gone, moving on to the next flower to extract its sugary nectar. This month look out for early arrivals: the bright yellow of the Brimstone, the Orange Tip, the Peacock, the silvery Holly Blue or the jagged wings of the Comma. But how do they make this journey to becoming a beautiful fluttering butterfly? We all know about the very hungry caterpillar, but what happens next?

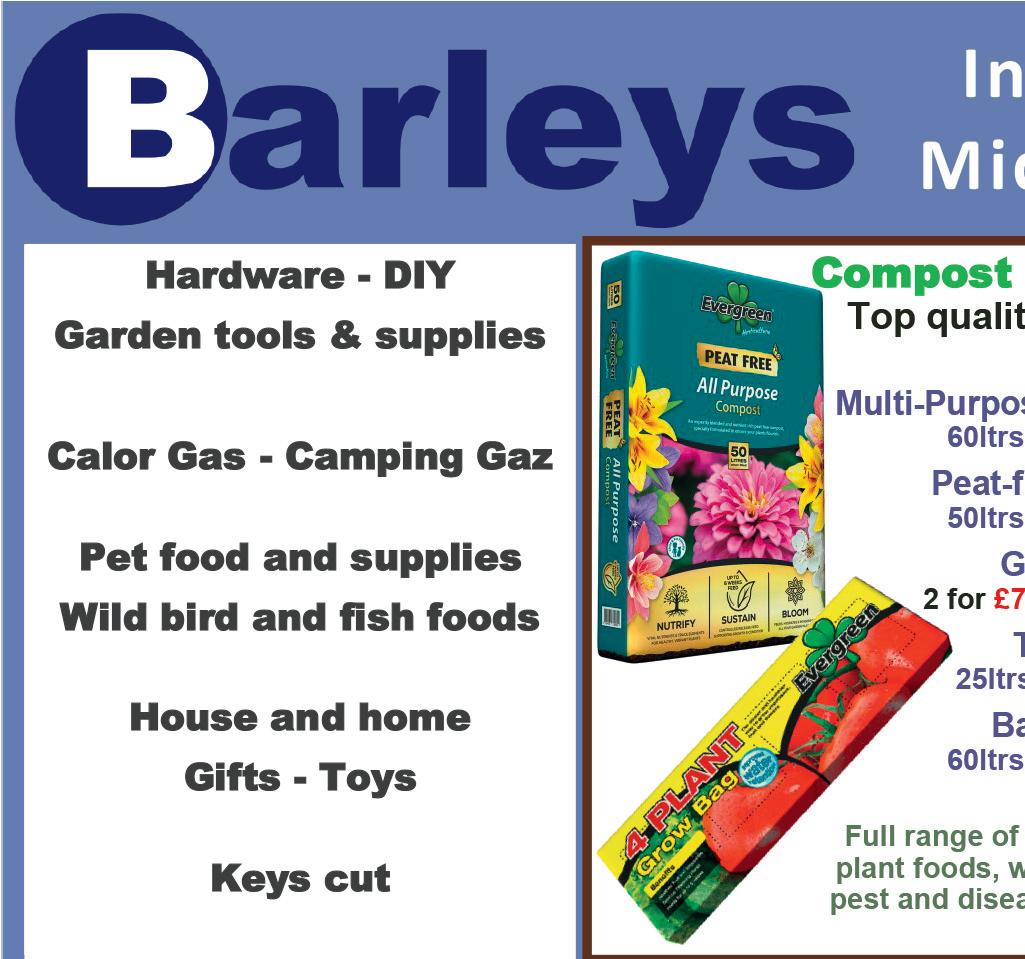

Advertisement

During its relentless leafy feast, the caterpillar (larvae) will go through a sequence of skin moults stimulated by a hormone called ecdysone, eventually spinning itself into a chrysalis to hang from the underside of a leaf or rock. The body will then release enzymes called caspases which dissolve most of the cells and reduce the caterpillar’s body down to a mushy, soupy slush. The cells which survive this process are called imaginal discs and they do the work in forming the body parts of the butterfly – the wings, the eyes, the legs.

You might ask – how do we know all this? The groundwork for understanding metamorphosis started over three hundred years ago, and the person who pioneered this research may surprise you.

Maria Sibylla Merian, born in Germany in 1647, was a superbly talented naturalist and illustrator. In 1699, aged fifty-two, she defied all convention and set off on a two-month sea voyage to the South American country of Suriname.

This in itself is fascinating for a woman of her generation, but her expedition didn’t stop there. Merian trekked into the depths of the dark, tangled undergrowth of the rainforests, under the high canopies of the treetops, and immersed herself in the sheer abundance of Suriname’s flora and fauna. She meticulously observed, sketched and documented the process of metamorphosis in butterflies and moths, completing an important and influential catalogue of work.

So if you find yourself at Pagham Harbour or Medmerry admiring the ephemeral beauty of a butterfly, consider not only the incredible transformation it’s made, but also the intrepid journey Maria Sibylla Merian made in order for us to understand it.

Why not join us on one or our guided walks this month to look for signs of spring, including the first butterflies of the year? Find out more by visiting our website: https://events.rspb.org.uk/ paghamharbour or call 01243 641508.

Walk And Chalk

BY SIMON BAKER IRONS

With the seasons changing and early signs of spring upon us what better way to see these changes than with a walk, deep in the South Downs, that takes in some fantastic views and follows an environmental sculpture trail through woods adorned with Wild Daffodils. This linear 5-mile route starts at the Cocking Hill car park and finishes in West Dean opposite the gates of the college. In 2002, Environmental Sculpturer Andy Goldsworthy, placed a trail of fourteen very large chalk balls in the area. The chalk used apparently came from the nearby Duncton Quarry and was carved into massive balls approximately 2-3m in diameter. The balls have been designed to erode and crumble over time but twenty years on, they are still there, albeit some are disintegrating more than others. Some of the stones are becoming overgrown and are hard to find, which makes for a great extreme Easter egg hunt.

1. From the car park the walk follows the South Downs Way uphill to the west, as the path ascends, the view north across the Sussex weald to Blackdown Hill is worth admiring.

2. About ¾ mile along the South Downs Way can be found the 1st chalk stone. At this point bear left on the bridleway and head towards West Dean Woods, more Chalk boulders can be found along the paths as the route unfolds.

3. The path passes through woods called ‘New Farm Plantation’ which is named after a ruin of an old, isolated smallholding, which fell into disuse in the 1950’s. The ruins can be explored just off the path.

4. Approximately a ¼ mile on, the bridleway heads south deeper into West Dean Woods.

5. A small clearing at the fifth stone is where thousands of Wild Daffodils cover the woodland ground in spring, these little flowers dominate in areas of coppice or light shade and in a good flowering year can be seen as a blanket of yellow. Displays of violets, Primroses, Wood Anemone, Bluebell and Orchid can also be seen.

6. The Bridleway heads south from the clearing, venturing further into the reserve of West Dean Woods. At the side of the path is a perfect example of a coppiced fence, using the Hazel that would have been coppiced from these woods over hundreds of years.

7. The Bridleway eventually meets a road and half of the chalk stones should have now been seen that have dotted the route.

8. The road heads straight along an uphill climb before descending round a sharp bend.

9. Just past the c.1800 cottage known as double barn, leave the road on the bridleway and head uphill through more woodland. The path then descends towards the end of the trail at West Dean and the last chalk stone can be found on the banks of the disused railway. A short bus ride from West Dean will take you back up to the car park on Cocking Hill.

To see more photos and walks please follow me on Instagram @piertopiertrekking