5 minute read

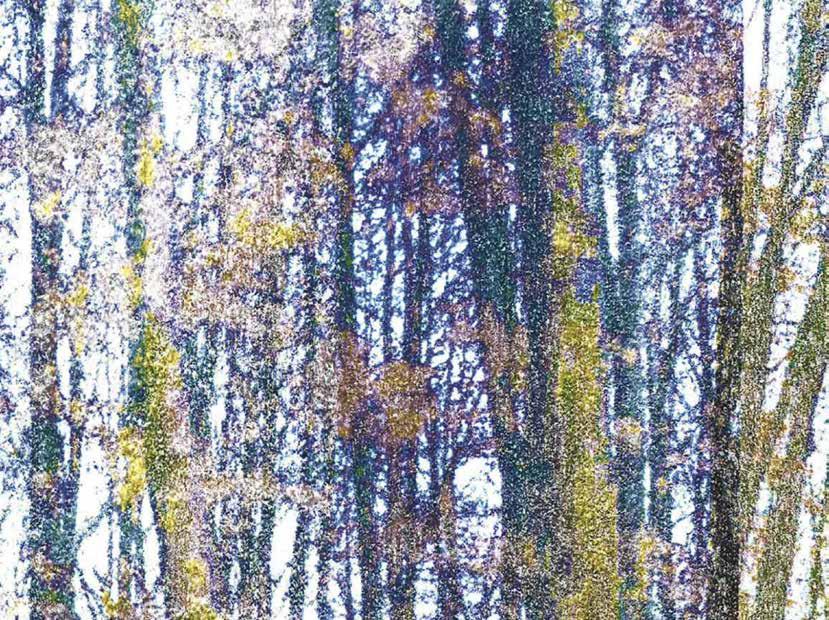

Cover Art: ‘Perception, Exposure and Reaction’

BSB Insider

Advertisement

Here, Sophie – one of our Press Room writers – addresses the serious issue of the current climate emergency.

The year 2022 began in much same way as many other recent one, with the planet facing yet another uncertain year. It seems to be a recurring theme: humanity manages to minimise the weight of our past mistakes with the devastation of our new ones. Unfortunately, this does very little to lessen the urgency of the issues we face, a major one of these being the climate crisis.

Last October saw the conclusion of the highly anticipated 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), widely dubbed a failure due to the lack of a substantial outcome following nearly two weeks of discussion. Though progress was made, with the finalisation of rules concerning emission reporting and carbon trading as well as agreements to “phase-down” the use of coal and prevent deforestation, many activists still had qualms about the pace at which change was being carried out by the world’s governments. The ambitions of the previous summit, the 2015 Paris Accords, were far from on track, with the target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C by 2030 seeming further out of reach than ever before. Generally, the main fault of COP26 lay in the inability of its participants to enforce crucial change; the climate crisis requires radical action, so why not act radically?

Unfortunately, things are not so straightforward. There are several reasons why our governments are hesitant to take the initiative, the majority of which are economic: the financial burden of decarbonising, resourcing renewable energy, and restricting major corporation production, is simply too much to shoulder. This, at least, is what most Western nations claim to be the impediment to change; however, such a sentiment is not exactly reflective of reality. The cost of sustainable technology is constantly dropping, it is now cheaper -and easier- than ever to reduce emissions. It is entirely possible to stimulate economic prosperity whilst keeping emissions in decline; however, this only remains true as long as we have enough time to implement change. The closer we edge to the end of the century, the more difficult it becomes to tackle the multiplying consequences of global warming. If we continue to waste time, the damage caused by the crisis will become infinitely more expensive to reverse than the crisis itself.

The issue here lies in the geography of climate change. From the torrential flooding across Western Europe to the incessant droughts that torment the Sahara, there is no denying that climate change does not discriminate: we have all fallen victim to the consequences of humanity’s choices. That being said, it is an undeniable fact that developing nations face the brunt of the crisis, with regional, economic, and political faults heavily influencing the gravity of its impact. This is evident when looking at India, which is currently facing the risk of a water crisis, a threat that is exacerbated by the nation’s struggling economy, high population and infrastructure issues. While a developed nation may be able to avoid the tipping point of such a crisis, developing countries do not have the financial capacity to correct it; a problem that is worsened by the decline of water resources caused by global warming.

Another aspect of climate change to consider is that most developing nations cannot be held responsible for it yet are forced to bear the ramifications. For example, the Philippines only contributes to 0.35% of the world’s yearly carbon emissions, yet suffers immensely from increasingly frequent typhoons, floods, and landslides caused by climate change. The region is highly susceptible to natural disasters due to its geographical position in the world’s most cyclone-prone area and is also at risk of other threats such as rising sea levels. This geographical vulnerability, when paired with the nation’s economic constraints, means the Philippines will endure the force of climate change at a much higher intensity than most other countries. The same notion applies to other developing Southeast Asian, African, and island nations. It is clear that Europe and North America do not share this sense of urgency, caused by the culmination of geographical and economic factors, when facing the climate crisis. There is less to incentivise Western nations to take financial action; less to instil pressure on their governments. Yet it is Western industries that play a leading role in accelerating the crisis: fossil fuel corporations like Shell and BP account for over 70% of the world’s global emissions, and Western consumers continue to use their products despite knowing the consequences. I cannot stress enough how important it is to stop being complicit in this. We must acknowledge our contribution to the climate crisis as individuals and take responsibility for our actions as a society.

Perception, exposure and reaction

By Crystal George

The cover design for this edition of Tapestry was created by BSB student Crystal, who revealed to us the inspiration behind her End of Year show and gave us some insight into her influences as an artist.

My final show comprised pieces shaped around the themes of “Perception, Exposure and Reaction”, which reflect the times we live in and the social and psychological changes in society perceived as a consequence of the pandemic.

With my work, I aim to challenge the concept of aesthetics in art. I was inspired by Baumgarten, a German philosopher, who associated aesthetics to signify a stimulation of our human senses rather than the contemporary idea of Art having to be a piece of beauty. Therefore, when producing work, I always hope that it can impact the viewer to connect to something more than the image itself.

With art having always been an important outlet for me, I am grateful for the opportunities and support I have had in developing this at BSB.

Magazine n°9 • 2022

Publisher

Melanie Warnes

Editor

Nick Amies

Production Manager

Carrie Stacchini

Contributors

Matej Bavec, Helen Beck, Paul Christmas, Tristian Cook, Maarten Couttenier, Huw Downing, Martin Gausseran, Crystal George, Nicola Gough, Luc De Groote, Clare Gunns, Emma Kedzierski, John Knight, Charlotte Lemaitre, Sophie Lindy, Christi-Ann Nancarrow, Amanda Nocera, Linda Ochsenmeier, Esther O’Connor, Adam Pickard, Charlie Phillips, Harriet Powell, Kate Ringrose, Neil Ringrose, Laura Sanderson, Ceri Seymour, Kheya Sinha, Jessica Southward, Nikolaus van der Pas, Tom Vuerinckx, Maurits Wesseling, Jane Whitehouse, Lieven Willems.