15 minute read

Assessment of Patient Knowledge and Awareness of Prosthodontics for Student and Patient Education and Communication

Assessment of Patient Knowledge and Awareness of Prosthodontics for Student and Patient Education and Communication

Mijin Choi, D.D.S., M.S., M.B.A.; Tejal Gohil, B.D.S.; Cristina Osorio, D.D.S.; Hannah Jeong; Thomas S. Giugliano, D.D.S.

ABSTRACT

This study evaluates patient understanding of the scope of prosthodontic treatments. Utilizing an 11-question survey, 149 patients at a postgraduate prosthodontic clinic were queried. Data analysis included frequency summaries, cross-tabulations and Pearson Chi-square tests. Results showed 68.4% of respondents knew about the role of prosthodontists. Their main concerns were improving chewing (43.9%) and smile (42.6%), varying by age. While many recognized prosthodontists’ scope, cosmetic and complex dental treatments were less well known as prosthodontic specialties. This highlights a gap in patient awareness regarding the full range of prosthodontic services.

The purpose of this research study was to understand patients’ level of awareness about prosthodontics via survey. The specialty has struggled with raising public awareness since prosthodontics was recognized by the American Dental Association as a specialty in 1947.[1] The American College of Prosthodontists (ACP) is helping to change public awareness through National Prosthodontics Awareness Week, via local and national proactive public relations tools, and training.

In the last five years, there have been efforts to increase the media presence of the prosthodontics specialty by the ACP. The ACP 2017 Public Relations Activities Summary reports there were 70,265 mentions of the terms prosthodontist and prosthodontics in social media and 13,119 in traditional media in 2017,[2] whereas in 2011, there were 864 traditional media mentions of these terms.[3] Presence in social and traditional media has become crucial in the overall effort to increase knowledge of the specialty. During Dr. John Agar’s ACP presidency in 2013-2014, the word “prosthodontist” was added to Microsoft’s spell check for the first time.[4] This illustrates how long the specialty has struggled to establish broader recognition in the minds of the public.

The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms 10th edition (GPT-10) defines prosthodontics as “the dental specialty pertaining to the diagnosis, treatment planning, rehabilitation, and maintenance of the oral function, comfort, appearance, and health of patients with clinical conditions associated with missing or deficient teeth and/or maxillofacial tissues by using biocompatible substitutes.”[5] This definition has not been helpful to the general public’s understanding of the complex restorative and reconstructive scope of dental care that only trained prosthodontists are educationally qualified to provide.

The belief that all general practitioners and prosthodontists possess an equal level of training is normally due to a lack of knowledge about the specialty. Determining if patients are aware of prosthodontic specialty services is a question of whether sufficient and effective marketing and patient education have been provided to the public.

According to a survey of 500 people, the criteria which are most important to people when finding a new dentist are, in order of importance, convenience in terms of distance and appointments, and online reviews.[6] Whereas in the past, before the use of social media as a referral tool, the public relied on word-of-mouth to satisfy their personal requirements for deciding on a dentist.[7,8] Oddly, the wordof-mouth recommendation is still the most powerful tool in marketing.

Prosthodontics as a specialty is just as mysterious to dental students as it is to the general public. In a 2020 survey of senior dental students, the students were asked about their confidence levels in various clinical skills and abilities. Eighty-one percent of seniors felt they received an adequate level of restorative clinical experience, while only 57% felt the same about the restoration of implants.[9] In the survey, prosthodontics (complex restorative dental care) was not part of the questions. However, the survey also indicated an upward trend of students seeking advanced education, from 35% in 2015 to 40% in 2020.

While these data do not address the need for further training in prosthodontics (complex restorative treatments), the recent trend reflects students’ desire to pursue advanced restorative education that includes implant restorative dentistry. The irony is that these same students, for the most part, feel they received adequate education (34.8% highly confident and 48.9% moderately confident) to carry out dental treatments for replacement of teeth, including fixed, removable and dental implant prosthodontics.

The survey presented here attempted to investigate the public’s knowledge of prosthodontics and prosthodontists. The hypothesis was that older age groups would have different preferred ways to learn about prosthodontists and different treatment concerns than younger age groups.

Materials and Methods

Eleven questions were designed for the study, and 149 survey responses were analyzed. The full survey questions are shown in tables 1a and 1b. An Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was received before beginning the survey (NYU Langone IRB S17-00318). The patients who presented in the postgraduate prosthodontic clinic were approached, and individuals who consented and were able to complete the survey in English were enrolled. The completed surveys were stored in a secure location in the principal investigator’s office. Data from the study was saved on a networked and password-protected computer.

Data Analysis and Data Monitoring

Data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet and exported to IBM SPSS (v28, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) for analysis. Data were summarized as the number and percentage responding to each question. The age groups were collapsed into two groups—18 to 65 and over 65—so that there were a similar number of participants in each group. Associations between responses to certain pairs of questions were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The survey questions and frequency analysis are shown in tables 1a and 1b. The makeup of the groups was 54.4% of participants were between the ages of 18 to 65, and 45.6% were above 65 years of age. On the question “How did you hear about NYUCD?” 46.2% indicated that family and friends were the most frequent source. TV/radio or internet advertisements only accounted for 7.5%. Also, 54.8% of the participants were referred by undergraduate and postgraduate clinics combined; 45.2% were referred by outside dentists or self-referred (Table 1a). Therefore, the majority of referrals were internal, from the New York University College of Dentistry. Finally, 80.8% of participants were existing patients in the prosthodontic clinic (Table 1a).

Regarding participants’ ongoing treatment experiences in the prosthodontic clinic, implant (48.3%), complete dentures (33.6%) and crowns (20.8%) were the most common responses (Table 1a).

The number one treatment concern was improving chewing ability (43.9%), followed by improving smile (42.6%) and replacing missing teeth (31.1%) (Table 1a). Other concerns listed were overall health, dental health, facial esthetics, finances, replacement of teeth, replacement restorations or prostheses, pain relief and treatments for failed restorations.

Participants’ past treatment experiences were mostly provided by prosthodontists and general dentists (Table 1b). General dentists (48.3%) were the most frequently visited previous dentists.

Regarding the question on how the participants learned about what a prosthodontist does (Question 9), 67.0% answered that they learned from previous students, general dentists or other specialists, while the remainder listed friends and family, news and advertisements (Table 1b).

On the question “Do you know what a prosthodontist is?” 68.4% answered “Yes” (Table 1b). When asked about the treatments prosthodontists provide (Question 10), most participants answered crowns (56.4%), bridges (55.0%), implants (60.4%), complete dentures (56.4%) and partial dentures (53.0%). Fewer listed “complicated treatments” (34.9%) and veneer (cosmetic) restorations (39.6%), and fewer yet thought prosthodontists provide braces and root canals (Table 1b).

Question 11 (Table 1b) asked about the preferred ways to learn about prosthodontists. The top two responses were “education by general dentists” (52.1%) and “Google search” (44.5%). Social media (7.6%) was their least preferred way. In the cross-tabulation analysis between age groups and social media as a way of learning about prosthodontists, both respondents 18 to 65 years old (87.5%) and 65 and above (98.2%) also chose social media as the least preferred way to learn about prosthodontists (Table 2, P = 0.028).

The participants’ responses on whether they previously received prosthodontic treatments (Question 7) were crosstabulated with the responses regarding the scope of care in the specialty of prosthodontics (Question 10). Participants who previously received treatment by prosthodontists were more likely to say that prosthodontists specialize in crowns (67.7%, P = 0.014), bridges (66.2%, P = 0.016), implants (70.8%, P = 0.023) and complete dentures (69.2%, P = 0.005). Although there was no statistical significance, it is important to mention that the many participants with past prosthodontic treatment experience did not recognize partial dentures (40.0%), complex treatments (60.0%) and cosmetic dentistry (58.5%) as scopes of treatments in prosthodontics (Table 3).

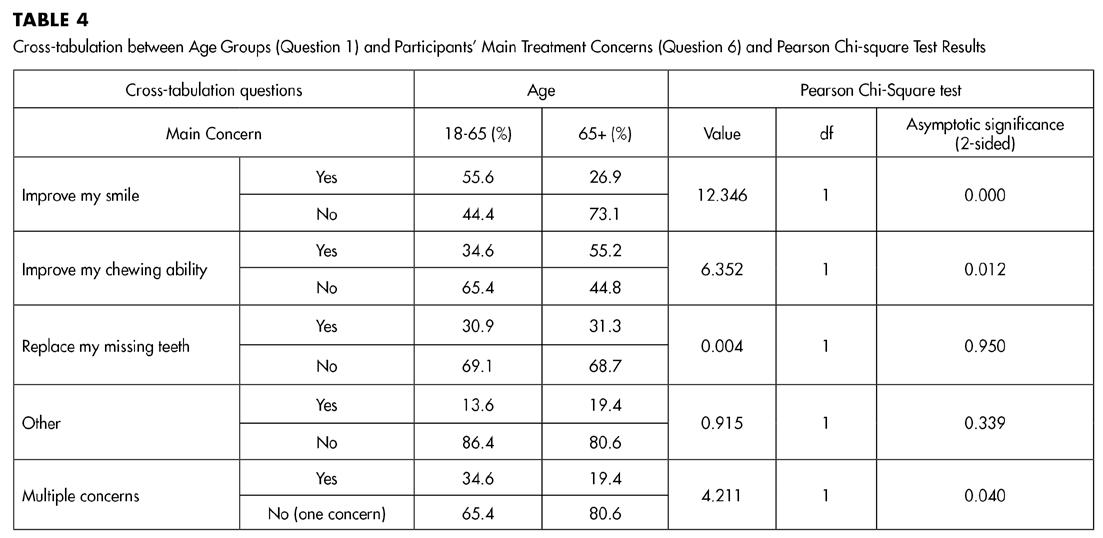

The participants’ main treatment concerns (Question 6) were related to age (Question 1). The 18-to-65 age group was more likely to be concerned with improving their smile (55.6%, P < 0.001) and had multiple concerns relative to the other participating age group. The over-65-age group was more concerned with improving chewing ability (55.2%, P = 0.012) than the 18-to-65 age group (Table 4).

Discussion

Demographics of Dental Specialties

According to the 2022 American Dental Association (ADA) Health Policy Institute Analysis, prosthodontists comprised less than 2% of all dental specialties, including general practice, making prosthodontics the sixth specialty in number among the 12 dental specialties recognized by the National Commission on Recognition of Dental Specialties and Certifying Boards (NCRDSCB). The growth of the number of prosthodontists from 2001 to 2022 was 13.7%. More than three-quarters (78.5%) of all practitioners are general dentists. The second-highest percentage of dental practitioners are orthodontists (5.4%), followed by pediatric dentists (4.4%). New York State has the third-highest number of dentists in the U.S., behind California and Texas.[10]

The first recognition of prosthodontics as a specialty by the ADA House of Delegates was in 1947. According to PubMed and Google Scholar search, using keywords “awareness AND prosthodontists,” “knowledge AND prosthodontists,” there were no articles published in the United States on the awareness or knowledge level of the general population regarding prosthodontists. Also, there was no research on how patients learned about prosthodontists and their preferred source of information regarding prosthodontists.

Patients’ Preferences for Learning about Prosthodontics

The participants in this study preferred to acquire information about prosthodontists first from their own general dentists, second via self-directed research through Google search, or third through friends and family members’ recommendations (Table 1b). These results showed that the credibility and trust of the source of information are most important. Their own dentists are professionals patients trust, and word-ofmouth (WOM) referrals by other people appeared to provide more confidence when selecting their new prosthodontist.

The power of direct personal communication, aka WOM marketing, has been working since the Stone Age. The story of traditional marketing is that one caveman found a good hunting area and spread the word to his friends. Before long, the place became the most popular hunting area because of WOM “marketing.”[11]

In the modern era, WOM marketing includes Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Google and Yelp reviews. With such an abundance of information, people must determine if the reviews are authentic and understand if self-perceived dental treatments should be provided by a prosthodontist. Moreover, the public must know what prosthodontists specialize in. Therefore, people are now looking for curated information by established organizations or by credible professionals.

One study conducted in Norway in 2000 looked at the public’s awareness of oral implant therapy. The study concluded that news media (newspapers and TV/radio) was rated as the most prevalent source of information. However, direct personal communication showed a more positive impact, indicating that personal communication with positive validation was regarded as a more reliable source of information.[12] This study also showed the same result, social media being the least preferred way of learning about prosthodontists or prosthodontics (Table 2).

These findings indicate that patient education would be more effective after gaining trust through credible marketing. Effective marketing should include

both simple patient education and content that includes the positive experiences of other people, as well as endorsements by well-known people with trusted credibility. People’s interests are sparked when positive experiences are shared by others who have had similar problems. Collecting testimonials from patients and sharing experiences on web-based platforms are important pieces in closing the gap between patient education and gaining trust.

Patients’ Perception

Participants with prosthodontic treatment experience gave implants the highest level of recognition as a treatment modality provided by prosthodontists, followed by complete dentures, then crowns and bridges. However, complex dental treatments (listed as complicated treatments in the survey) were not recognized as the scope of care provided by prosthodontists in 60.0% to 69.1% of the responses regardless of prosthodontic treatment experience (Table 3).

As the definition of prosthodontics by the GPT-10 does not include specific dental treatment modalities, educating patients and dental students on what a prosthodontist does has been a challenge. The difficulties in defining the scope of care in prosthodontics further complicated the perceptions of the public and dentists on when a referral should be made for complex oral and esthetic rehabilitative or reconstructive dental treatments. Defining the scope of prosthodontic care that includes dental treatment modalities will ultimately help to improve understanding of prosthodontics by patients, dental students and other dental professionals.

Patients’ Treatment Concerns

For statistical analyses, participants were divided into two age groups: 18 to 65 and older than 65. In the younger group, smile improvement was the main oral health concern, followed by chewing ability. Improving chewing ability was the main concern in the older group (Table 4). These findings are not surprising because as people age, function may become a higher priority than esthetics for the majority of people.

Recognition of Prosthodontic Treatments

The first definition for prosthodontics under the Google search states, “the branch of dentistry concerned with the design, manufacture, and fitting of artificial replacement for teeth and other parts of the mouth.” How can we describe what a prosthodontist does in short sentences for the general public’s understanding? Surely we have been challenged with this since the beginning. Do the explanations of our specialty include treatment modalities that other specialties or dental school education do not provide? We are educationally qualified to perform complex oral rehabilitative and reconstructive dental treatments. For the general public, not as a full definition for the GPT-10, we propose the following statement:

“Prosthodontists specialize in complex dental treatments that may involve high-level esthetic restorations with implants, crowns, bridge, and dentures for missing and defective teeth and jaw structures.”

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the number of participants was relatively small for a strong qualitative survey study. All study participants received information about prosthodontics because the participants were referred for prosthodontic consultation and treatment. Therefore, the findings were used to analyze the effectiveness of the information provided about prosthodontists.

A larger sample size with dental patients who may or may not have prior experience with prosthodontists would have yielded improved insight into the public’s knowledge about the prosthodontic specialty. Furthermore, a multicenter study that includes a broader spectrum of patients would reduce convenience bias.

Despite continued efforts to educate the public and students, describing the specialty of prosthodontics remains a challenge. This study showed that, on average, 57% of participants recognized the common services provided by prosthodontists, such as crowns, bridges, implants and complete dentures. And, on average, only 37% of participants recognized cosmetic dentistry and complex treatments as being within the prosthodontic scope of care. These findings showed that efforts to increase awareness about prosthodontists among the general public should include more emphasis on educating patients with a simple and clear description about prosthodontics. Providing a better description about the scope of prosthodontic treatments may enable more effective and efficient communication between patients and dentists.

The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study.

Queries about this article can be sent to Dr. Choi at mc185@nyu.edu.

REFERENCES

1. Transactions of the American Dental Association 1947:80-1.

2. Barth C. Summary Report: 2017 ACP Public Relations Activities, 2017. www.prosthodontics. org/acp-publications/annual-reports/ [Accessed 11 December 2023].

3. Barth C. Summary Report: 2015 ACP Public Relations Activities, 2015. www.prosthodontics. org/acp-publications/annual-reports/ [Accessed 11 December 2023].

4. ACP press release dated November 21, 2014. https://www.prosthodontics.org/assets/1/7/ Agar_Past_President-_na_cb_jra_approved_11-21-14.docx.pdf [Accessed 7 September 2020].

5. Layton DM (Ed.), Morgano SM, Muller F, Kelly JA, Nguyen CT, Scherrer SS, et al. Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms 2023: 10th edition. J Prosthet Dent 2023;130(4S1):e1-e126. PII: S002-3913(23)X0002-X.

6. DentalIQ.com: 2013. https://www.dentistryiq.com/practice-management/article/16354970/ convenience-honesty-and-online-reviews-some-of-the-things-your-dental-patients-want/ [Accessed 1 September 2020].

7. Garry JF. How (and why) patients choose a dentist and stay with him. Orange Cty Dent Soc Bull 1972:5.

8. Book DS, Stockton HJ. Why patients choose a particular dentist. J Can Dent Assoc 1986;52:123-6.

9. Istrate EC, Slapar FJ, Mallarapu M, Stewart DCL, West KP. Dentists of tomorrow: an analysis of the results of the 2020 ADEA Survey of US dental school seniors. J Dent Educ 2021;85:427-40.

10. Supply of Dentists in the U.S.: 2001-2022. https://www.ada.org/en/resources/research/ health-policy-institute/dentist-workforce [Accessed 11 December 2023].

11. Whitler K. Forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimberlywhitler/2014/07/17/why-word-ofmouth-marketing-is-the-most-important-social-media/#7c444f1454a8 [Accessed 2 July 2020].

12. Berge TI. Public awareness, information sources and evaluation of oral implant treatment in Norway. Clin Oral Impl Res 2000;11:401-8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011005401.x

Mijin Choi, D.D.S., M.S., M.B.A., FACP, is clinical professor, Department of Prosthodontics, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

Tejal Gohil, B.D.S., is clinical assistant professor, Department of Comprehensive Dentistry, University of Texas Health San Antonio School of Dentistry, San Antonio, TX.

Thomas S. Giugliano, D.D.S., is clinical assistant professor, Department of Prosthodontics, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY.

Cristina Osorio, D.D.S., is in private practice in Miami, FL

Hannah Jeong, is a fourth-year predoctoral dental student, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, NY