15 minute read

Parents’ Acceptance of Topical Fluoride Varnish in a Primary Care Medical Setting

Michelle Ferraioli, D.D.S.; Dana Sirota, M.D., M.P.H.; Christie Lumsden, Ph.D.; Richard Yoon, D.D.S.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To examine parental knowledge and acceptance of topical fluoride varnish (FV) use in a primary care medical setting for the prevention of dental caries among high-risk children.

Methods: Fifty English-speaking parents of children 6 months to 6 years of age presenting for wellchild visits in the waiting room of a pediatric and adolescent community health center in Washington Heights, NY, were asked to participate. Following an explanation of the benefits of FV and application method, a 5-minute, 19-item, close-ended questionnaire assessing demographic characteristics, oral health knowledge and opinions towards FV in a medical setting was completed.

Results: Out of 50 parents approached, 45 participated. Sixty percent (n=27) had never heard of FV and, following an explanation of the application method, 67% (n=30) were unconcerned about the temporary discoloration. Ninety-six percent 96% (n=43) would allow the primary care physician (PCP) to apply FV, 98% (n=44) would not stop brushing their child’s teeth if FV was applied; and 91% (n=41) would not miss routine dental visits if applied in a primary care medical setting.

Conclusion: Despite methodological limitations that limit generalization, including small sample size and recruitment of only English-speaking parents, results suggest that parents of young children are accepting of FV application in the primary care medical setting and would not change homecare habits or dental routines if FV is applied. These findings support the adoption of FV application in primary care medical settings as a dental caries primary prevention/early intervention strategy.

The prevalence of dental caries in low-income U.S. children under the age of 5 is high (34.7%) compared to children from higherincome families (16.5%).[1,2] Further, significantly higher rates are reported for minority groups, particularly Hispanic children.[1,3,4]

As a highly prevalent chronic disease that affects health and wellbeing throughout life, causing pain, infection, and interfering with social and family interactions, caries imposes a significant burden on children and their families.[5]

Topical fluoride varnishes (FV) are one of the few evidencebased primary prevention/early intervention treatments available for dental caries in at-risk children, and its use is endorsed by several national health organizations as part of a comprehensive pediatric dental caries prevention education program.[6-8] The efficacy of FV in primary teeth when used at least twice a year has been reported in numerous randomized, controlled trials, which show dental caries reduction rates ranging from 25% to 40%.[9-13]

Since parents of very young children see the primary care physician (PCP) earlier (from birth) and more frequently (10 visits by the 18th month of age) than they see the dentist, the primary care medical setting holds potential to effectuate true primary prevention education and anticipatory guidance to combat dental caries.[14,15] Dental caries prevention through PCPs may be a particularly beneficial approach for very high-risk population groups, including low-income, Hispanic and immigrant children, who are disproportionately burdened by dental caries yet often experience numerous barriers to dental care. While, on average, 84% of Medicaid-enrolled children receive a pediatric medical well-child visit, only one-in-three children enrolled in Medicaid visit a dentist at least once a year.[16] Since 2017, Medicaidenrolled PCPs in all states across the U.S. are eligible to receive reimbursement for providing oral health screenings and FV application to young children, further supporting this approach to caries prevention.[17,18,19]

The pediatric medical and dental clinics affiliated with Columbia University Medical Center in northern Manhattan serve a very high-risk catchment area, in which preschool children experience dental caries at prevalence rates three-times higher than reported in nationally representative data.[20,21] To inform expansion of dental caries primary prevention efforts by PCPs serving such high-risk populations, the present study sought to evaluate parental oral health knowledge and acceptability of FV application for their children in a primary care medical setting.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a pediatric and adolescent community health center at the Columbia University Medical Center located in northern Manhattan, in Washington Heights— one of the most economically disadvantaged communities in New York City. This diverse community of approximately 200,000 persons is 71% Latino (the majority from the Dominican Republic), 17% white, 7% black, 3% Asian and 1% other.[22] One-third of the community meets federal poverty guidelines standards.[20-22]

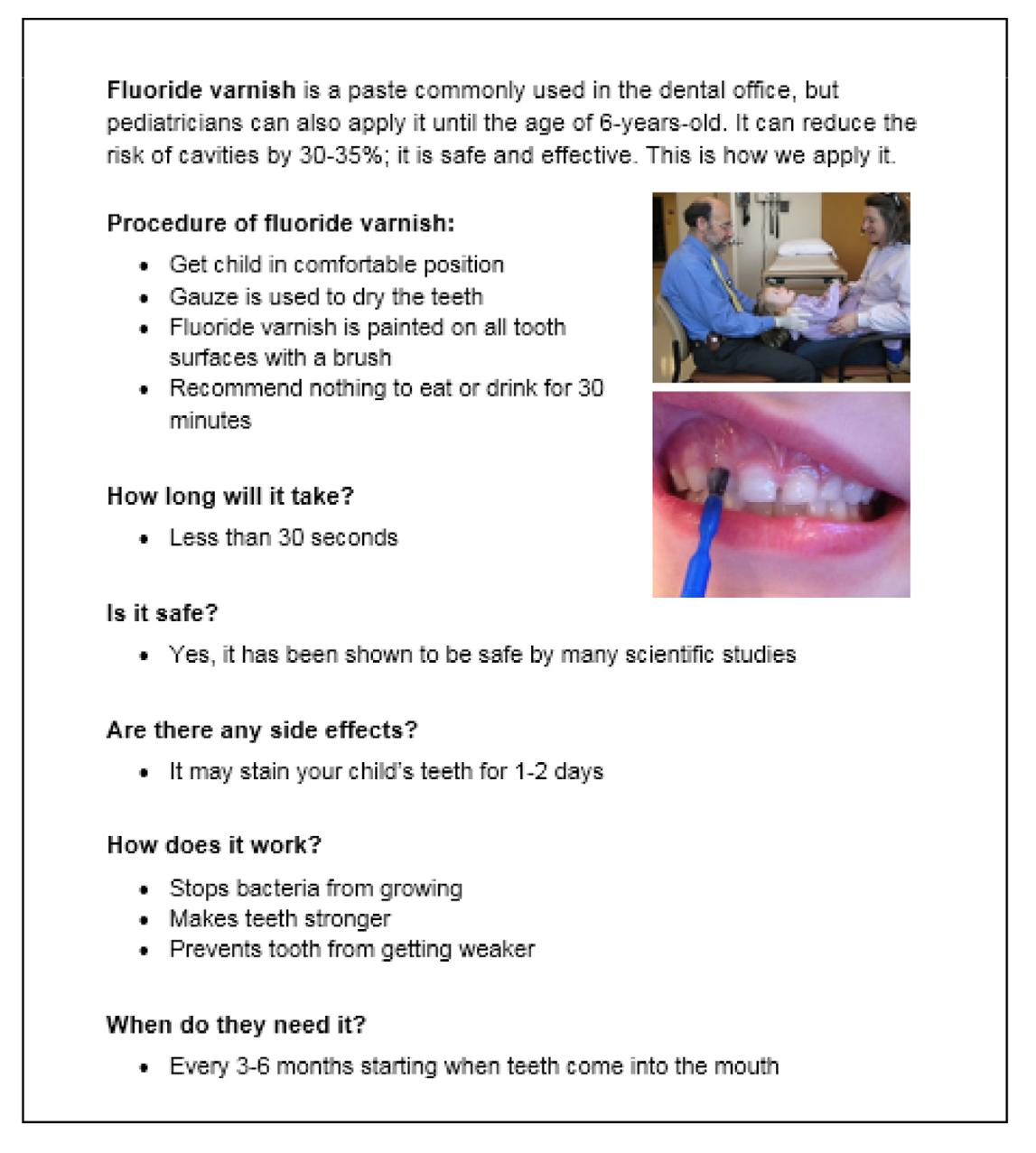

A convenience sample of English-speaking parents with children aged 6 months to 6 years who presented to the community health center for well-child and sick visits were recruited from the center’s waiting room. After obtaining verbal consent to participate, a single investigator (MF) individually provided participating parents with a verbal explanation of the FV application procedure, including the potential benefit of reduced dental caries and the risk of mild enamel fluorosis, supported by a visual aid (adapted from Smiles for Life®) demonstrating the procedure (Figure 1).[23] Following this two- to three-minute explanation, the parent completed a 19-item, paper-based survey, verbally administered by the investigator, that assessed sociodemographic variables, oral health knowledge and opinions regarding FV application by a PCP.[23]

Figure 1. Copy of handout used to explain fluoride varnish application procedure to parents (adapted from Smiles for Life®).[23]

The survey instrument was adapted from a study by Hendaus et al. (2016), who evaluated parental attitudes regarding FV application in a medical setting and its impact on oral health habits. [24] Sociodemographic questions assessed parent age and child age, number of children under the age of 5 years for whom the parent is the primary caregiver, employment status and high school or GED diploma status. Oral health knowledge questions assessed parental thoughts regarding the influence of diet (content and frequency) on dental health and at-home oral hygiene. Attitudes with respect to FV were determined by assessing parental concerns about FV safety or temporary discoloration, how they felt about allowing PCPs to apply FV, and whether such FV application would affect routine dental visits and oral hygiene behaviors.

Data were collected anonymously, without identifying information, between June 2017 and November 2017. Study procedures, including a waiver of written informed consent, were approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (protocol number AAAR2654). Descriptive statistical analyses and Fisher’s Exact tests were completed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY), with statistical significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Forty-five parents, out of 50 approached for participation, were enrolled in this study. Just over half of the parents were aged <30 years (56%), with the remainder ranging from 30 to 39 years (35%) and 40 to 50 years (9%). The average age of participating parents was 29 years; children were, on average, 2.8 years of age. The majority of parents reported being the primary caregiver of one child under the age of 5 years (80%, n=36), with few reporting being the caregiver of two or three children under 5 years (18%, n=8 and 2%, n=1, respectively). Over one-quarter of parents (29%, n=13) were unemployed; 33% (n=15) were employed outside the home part time; and 38% (n=17) were employed outside the home full time.

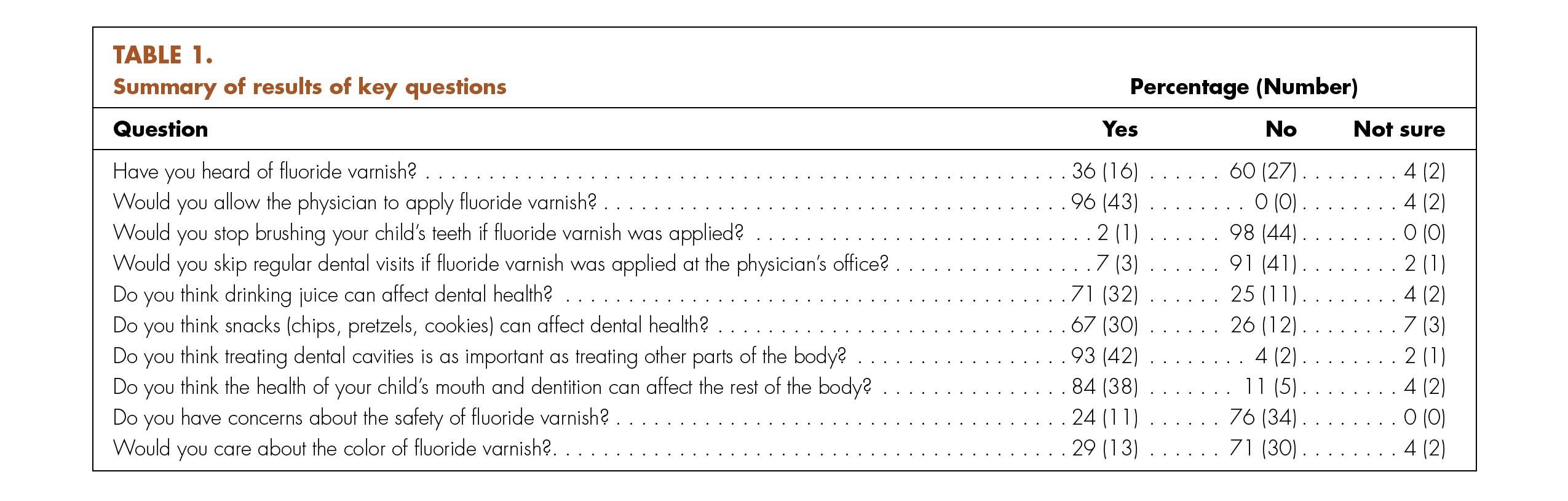

Approximately 80% (n=36) had graduated from high school or received a GED. Findings reveal that 60% (n=27) of parents surveyed had not heard of FV prior to this study. Following an explanation of the FV application procedure, over two-thirds of parents (67%, n=30) were not concerned about the temporary discoloration related to the procedure; 96% (n=43) would allow the PCP to apply FV; 98% (n=44) would not stop brushing their children’s teeth if FV was applied; and 91% (n=41) would not skip routine dental visits if FV was applied in a primary care medical setting (Table 1).

The majority of parents provided accurate responses to knowledge questions with respect to the impact of dietary frequency and content on dental health (Table 1). The majority of parents thought that dental health affects overall health (84%, n=38). Associations between parent education level and questions assessing oral health knowledge (e.g., Do you think snacks such as chips, pretzels, crackers and cereal can affect dental health? Do you think the health of your child’s mouth and dentition affect the rest of the body?) were not statistically significant.

Relationships between parental concerns about safety (i.e., Do you have concerns about the safety of fluoride varnish?) or color of FV (i.e., Would you care about the color of fluoride varnish?) and parent willingness to allow children to receive FV in a primary care medical setting revealed that the majority of parents were not concerned about FV safety (76%, n=34) or temporary discoloration of teeth due to FV application (67%, n=30). Parents who expressed concern about the color or safety of FV were no less likely to allow their PCPs to apply FV for their child than those who had no concerns.

Discussion

Though FV application has been shown to be effective in reducing caries incidence (from 25% to 40%),[9-13] most state Medicaid programs reimburse medical providers for its application and oral health screenings in young children[16-17] and national health organizations support the practice—there remains uncertainty among clinicians about the acceptance and impact of FV application by PCPs. There have been anecdotal reports that dentists are concerned that if FV is applied at the pediatrician’s office, parents may think it is a replacement for regular home care or may replace regular dental visits.

While there are several effective approaches to dental caries prevention, available dental services are often underutilized in many high-risk communities.[25] Despite this non-traditional approach, the application of FV in the primary care medical setting holds potential to reduce caries incidence in vulnerable subpopulation groups. The present study sought to address some of these concerns by replicating a study by Hendaus et al. (2016),[24] the objective of which was to determine parents’ thoughts and attitudes towards FV application in a primary care medical setting by PCPs, and what impact it might have on oral health habits.

Interestingly, the overwhelming majority (96%) of the parents surveyed in this study within a high-risk population would allow the pediatrician to apply FV. This finding suggests high parental acceptance of this primary prevention and early intervention measure, traditionally dental in nature, being received in a medical setting. These findings are consistent with a study by Adams et al. (2009), which found a high parental preference for early intervention measures like FV and toothbrushing with a fluoridated dentifrice over other products (e.g., chlorhexidine and xylitol) in a similar population.[25] Adams et al. (2009) studied 211 parents’ preferences for five childhood caries early intervention measures for Hispanic children, concluding that all treatments were highly acceptable, but FV and toothbrushing were preferred over other treatment methods. One reason why parents may be more accepting of topical fluorides could be the familiarity of this early intervention method in the routine and general dental setting.

In the primary care academic medical setting, where interdisciplinary care is foundational, oral health information is often being shared with parents by PCPs, even if the patient has yet to see the dental provider. Primary care physicians may be emphasizing the importance of seeing a dentist as part of a child’s biannual checkup routine. This may provide some explanation for why nearly all parents in this study reported they would not avoid regular dental visits if FV was applied by the PCP in a primary care medical setting and why no statistically significant associations were found with oral health knowledge variables.

While there have been studies that examined topical FV application in the primary care medical setting, few have focused on parental attitudes and perceptions of FV. Though conducted abroad, the study by Hendaus et al. (2016), on which the present study was based, found similar levels of oral health knowledge and parental acceptability of PCP-applied FV: Greater than 90% of families were aware of dental health as a component of overall health; 70% had never heard of FV but would allow the PCP to apply it; and approximately 80% of parents would not stop brushing their child’s teeth or skip brushing if FV was applied.[24] Similar to the present study, the authors concluded that FV applied in a primary care medical setting was both feasible and acceptable within the community.

Moreover, the study by Adams et al. (2012), which evaluated preferences for early childhood caries intervention methods among 48 parents of young African-American children, also supports high parental acceptability of FV application. Interestingly, while FV and all other treatments assessed were deemed acceptable, toothbrushing was found to be significantly more acceptable to parents than FV and other early intervention measures.[26]

These data must be interpreted with caution and may not be widely generalized due to the limitations of the study, including a small sample size and relatively homogeneous population. Further, all aspects of the study were conducted in the English language in a predominantly Hispanic immigrant community where Spanish is commonly spoken. As a result, the conclusions drawn may not accurately reflect parents’ attitudes within the target population. Despite these limitations, the consistency of responses suggesting parents are supportive of the use of FV for primary prevention has been shown in our study, as well as in studies conducted by Hendaus et al. (2016),[24] Adams et al. (2009),[25] and Adams et al. (2012).[26] Collectively, these studies represent a much larger sample size of parents from different backgrounds who have similar attitudes regarding the benefits of FV. However, future studies should be conducted with a larger sample size, including both English- and Spanish-speaking participants, to gain a more precise understanding of parental knowledge and opinions regarding topical FV application.

The findings of this study support the use of topical FV as a primary dental caries prevention modality in the primary care medical setting. This approach has the potential to decrease caries incidence, particularly in underserved communities that generally suffer the greatest burden of disease, since children see the PCP significantly more in the first few years of life than they do dental professionals.[14]

Understanding parents’ attitudes can help the PCP and the dentist provide better preventive care with an overall goal of reducing the burden of dental disease in high-risk communities. Findings support the use of dental interventions in a medical setting as part of a primary prevention education and anticipatory guidance scheme. Subsequent evaluation with a larger sample may provide additional insight into ways in which early intervention and medical-dental care programs may be tailored for high-risk communities. p

Authors’ research was supported by Health Resources and Services Administration/ DHHS, Postdoctoral Training in General, Pediatric and Public Health Dentistry, D88HP20109. The authors report no conflict of interest in the preparation of this paper. Queries about this article can be sent to Dr. Yoon at rky1@cumc.columbia.edu.

REFERENCES

1. Dye BA, Mitnik GL, Iafolla TJ, Vargas CM. Trends in dental caries in children and adolescents according to poverty status in the United States from 1999 through 2004 and from 2011 through 2014. J Am Dent Assoc 2017 Aug 1;148(8):550-65.

2. Benjamin RM. Oral health: the silent epidemic. Public Health Rep 2010;125(2):158-159.

3. Macek MD, Heller KE, Selwitz RH, Manz MC. Is 75 percent of dental caries really found in 25 percent of the population? J Public Health Dent 2004;64(1):20-25.

4. Dye BA, Hsu KL, Afful J. Prevalence and measurement of dental caries in young children. Pediatr Dent 2015;37(3):200-16.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Rockville, MD: 2000. Available at: https://www.nidcr.nih.go /DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/Documents/ hck1ocv.@www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2018.

6. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride Therapy. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(6):242-245.

7. Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, et al. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91.

8. Moyer VA. US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics 2014;133(6):1102-11.

9. Holm AK. Effect of fluoride varnish (Duraphat) in preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1979;7(5):241-5.

10. Clark DC, Stamm JW, Robert G, Tessier C. Results of a 32-month fluoride varnish study in Sherbrooke and Lac-Megantic, Canada. J Am Dent Assoc 1985;111(6):949-53.

11. Autio-Gold JT, Courts F. Assessing the effect of fluoride varnish on early enamel carious lesions in the primary dentition. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132(9):1247-53.

12. Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Jue B, et al. Fluoride varnish efficacy in preventing early childhood caries. J Dent Res 2006;85(2):172-6.

13. Bonetti D, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnish for caries prevention: efficacy and implementation. Caries Res 2016;50(1):45-49.

14. Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017.

15. Kolstad C, Zavras A, Yoon RK. Cost-benefit analysis of the age one dental visit for the privately insured. Pediatr Dent 2015;37(4):376-380.

16. Bouchery E. Utilization of dental services among Medicaid-enrolled children. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2013;3(3):mmrr.003.03.b04. doi:10.5600/mmrr.003.03.b04.

17. Isong IA, Silk H, Rao SR, Perrin JM, Savageau JA, Donelan K. Provision of fluoride varnish to Medicaid-enrolled children by physicians: the Massachusetts experience. Health Serv Res 2011;46(6 Pt 1):1843-1862.

18. Kranz AM, Rozier RG, Preisser JS, Stearns SC, Weinberger M, Lee JY. Preventive services by medical and dental providers and treatment outcomes. J Dent Res 2014;93(7):633-638.

19. Reimbursing physicians for fluoride varnish. Pew Research Center. Accessed July 13, 2018 at http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2011/08/29/reimbursingphysicians-for-fluoride-varnish.

20. Prevalence of Untreated Dental Caries in Primary Teeth Among Children Aged 2-8 Years, by Age Group and Race/Hispanic Origin—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:261.

21. Albert DA, Findley S, Mitchell DA, Park K, McManus JM. Dental caries among disadvantaged 3- to 4-year-old children in northern Manhattan. Pediatr Dent 2002;24(3):229-233.

22. King L, Hinterland K, Dragan KL, Driver CR, Harris TG, Gwynn RC, Linos N, Barbot O, Bassett MT. Community Health Profiles 2015, Manhattan Community District 12: Washington Heights and Inwood; 2015;12(59):1-16.

23. Silk H, Douglass A, Clark M, et al. Smiles for Life National Oral Health Curriculum: Module 6. Fluoride Varnish. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2012.

24. Hendaus M, Jamha H, Siddiqui F, Elsiddig S, Alhammadi A. Parental preference for fluoride varnish: a new concept in a rapidly developing nation. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1227-1233.

25. Adams SH, Hyde S, Gansky SA. Caregiver acceptability and preferences for early childhood caries preventive treatments for Hispanic children. J Public Health Dent 2009;69(4):217-224.

26. Adams SH, Rowe CR, Gansky SA, Cheng NF, Barker JC, Hyde S. Caregiver acceptability and preferences for preventive dental treatments for young African-American children. J Public Health Dent 2012;72(3):252-260.