7 minute read

Study about Venus could provide insight into Earth’s future

Report identifies, compares atmosphere, geology of Venus-like planets

BY NOAH CHEN CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Advertisement

A recent study co-authored by James Head, professor emeritus of geological sciences and professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences, investigates why Venus is so different from Earth — despite the two planets’s physical similarities — and the implications for Earth’s future. The study, published in March, was a collaboration alongside researchers from the southwest Research Institute, the University of California at Santa Cruz and the University of California at Riverside.

No other planet in the solar system shares as many similarities to Earth as Venus in terms of size and structure. Modeling the history of Venus could provide insight as to why the planets became so different — surface temperatures on Venus reach 900 degrees Fahrenheit, and sulfuric acid fills the atmosphere, according to NAsA.

“The question is, how does something so similar have such a different atmosphere? And what are the causes of that?” Head said. “It’s not clear how long the Venus atmosphere has been there. We only have about 20% of the geological record.”

By looking to answer these questions, researchers aim to learn more about planet habitability and planet evolution. Data can further reveal information about the criteria needed for life to survive.

The study uses data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive, a compilation of data from observatories around the world. In the study, researchers iden- tified over 300 Venus-like exoplanets, or planets outside the solar system.

“Venus is the most similar planet to Earth in the solar system. And we don’t really fully understand why Venus is so different from Earth, even though they are so physically similar,” said Colby Ostberg, a fifth-year PhD student at UC Riverside and head researcher of the study. “Observing exoplanets is a pathway to understanding what happened to Venus. We observe planets that have similar energy received from their star compared to Venus.”

“Planets like Venus are a real warning to us,” said stephen Kane, professor of planetary astrophysics at UC Riverside, adding that understanding planets like Venus can reveal how planets can evolve — “how you get a habitable planet rather than a hostile planet.”

The criteria to select the 300 planets was based on planetary size, energy from a nearby star and the temperature level of that star. These planets were said to lie in the “Venus Zone,” which describes planets too hot to have surface liquid, but not so hot that the atmosphere is completely stripped away.

“The Venus Zone is the region around a star where a terrestrial planet will likely have an atmosphere pushed into a ‘post-runaway greenhouse state,’” Kane explained. In the post-runaway greenhouse state, excessive carbon dioxide in the atmosphere traps heat, causing surface liquids to boil away.

“For Venus, we see a very thick carbon dioxide-dominated atmosphere,” Kane added.

The list of Venus Zone exoplanets was then narrowed down to five most closely resembling Venus, according to the study. The five exoplanets will be observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, the largest optical telescope in space, and examined by researchers at the NASA Goddard Institute for s pace s tudies in New York.

With data on the identified planets, NASA GISS could run 3D climate models on the planets, according to Kane. Those models could help researchers model the planetary history of Venus — and even explain what transpired to make Venus so uninhabitable.

According to Michael Way, phys - ical scientist at NASA GISS, he and others are working with a complex digital program capable of modeling the atmosphere, land surface and ocean of planets. “It’s all coupled together in like three million lines of code, and it runs on the biggest supercomputers we have at NA s A,” he said.

“We take that model and we can use it to model ancient Venus or an - cient Mars, and the atmospheres of the planets. They will tell us what the atmosphere is made out of,” Way explained. “And then we can do detailed modeling to see whether that atmosphere could support a liquid ocean or not, for example.” findings

“That’s very important for the search for life, and also important for understanding the potential future of Earth,” Kane said.

The project was inspired when fifth-year Neurosurgery Resident and Co-first author Rohaid Ali was studying for his neurosurgery board exam with his close friend from s tanford Medical s chool, Ian Connolly, another co-first author and 4th year neurosurgery resident at Massachusetts General Hospital. They had seen that ChatGPT was able to pass other standardized exams like the bar examination, and wanted to test whether ChatGPT could answer any of the questions on their exam.

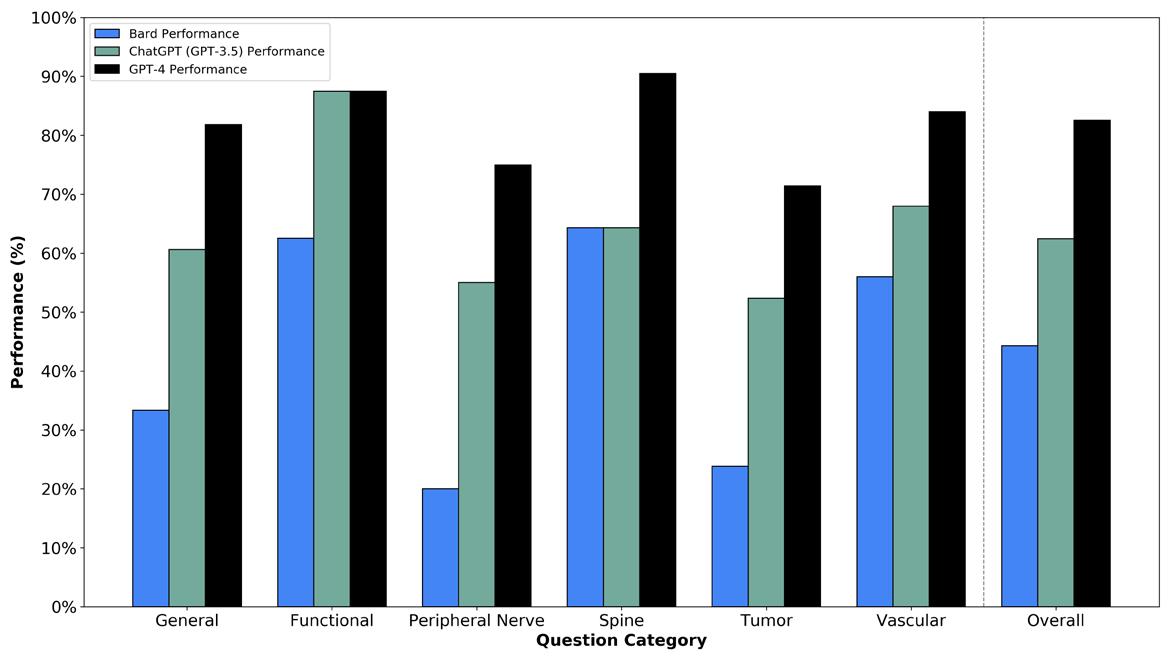

This prompted Ali and Connolly to execute these studies in collaboration with their third co-first author, Oliver Tang ’19 MD’23. They found that GPT-4 was “better than the average human test taker” and ChatGPT and Google Bard were at the “level of the average neurosurgery resident who took these mock exams,” Ali said.

“One of the most interesting aspects” of the study was the comparison between the AI models, as there have been “very few structured head-to-head comparisons of (them) in any fields,” said Wael Asaad, associate professor of neurosurgery and neuroscience at Warren Alpert and director of the functional epilepsy and neurosurgery program at RIH. The findings are “really exciting beyond just neurosurgery,” he added. The article found that GPT-4 out- performed the other LLMs, receiving a score of 82.6% on a series of higher-order case management scenarios presented in mock neurosurgery oral board exam questions.

Asaad noted that GPT-4 was expected to outperform ChatGPT — which came out before GPT-4 — as well as Google Bard. “Google sort of rushed to jump in and … that rush shows in the sense that (Google Bard) doesn’t perform nearly as well.”

But these models still have limitations: As text-based models cannot see images, they scored significantly lower in imaging-related questions that require higher-order reasoning. They also asserted false facts, referred to as “hallucinations,” in answers to these questions.

One question, for example, presented an image of a highlighted portion of an arm and asked which nerve innervated the sensory distribution in the area. GPT-4 correctly assessed that it could not answer the question because it is a text-based model and could not view the image, while Google Bard responded with an answer that was “completely made up,” Ali said.

“It’s important to address the viral social media attention that these (models) have gained, which suggest that (they) could be a brain surgeon, but also important to clarify that these models are not yet ready for primetime and should not be considered a replacement for human activities currently,” Ali added. “As neurosurgeons, it’s crucial that we safely integrate AI models for patient usage and actively investigate their blind spots to ensure the best possible care for the patients.”

Asaad added that in real clinical scenarios, neurosurgeons could receive misleading or irrelevant information. The LLMs “don’t perform very well in these real-world scenarios that are more open-ended and less clear cut,” he said.

Ethical considerations with medicine and AI

There were also instances where the AI model’s correct response to certain scenarios surprised the researchers.

For one question about a severe gunshot injury to the head, the answer was that there is likely no surgical intervention that would meaningfully alter the trajectory of the disease course. “Fascinatingly, these AI chatbots were willing to select that answer,” Ali said.

“That’s something that we didn’t expect (and) something that’s worth considering,” Ali said. “If these AI models were going to be giving us ethical recommendations in this area, what implications does that have for our field or field of medicine more broadly?”

Another concern is that these models are trained on data from clinical trials that have historical - ly underrepresented certain disadvantaged communities. “We must be vigilant about potential risks of propagating health disparities and address these biases … to prevent harmful recommendations,” Ali said.

Asaad added that “it’s not something that’s unique to those systems — a lot of humans have bias — so it’s just a matter of trying to understand that bias and engineer it out of the system.”

Telfeian also addressed the importance of human connections between doctors and patients that AI models still lack. “If your doctor established some common ground with you — to say ‘oh, you’re from here, or you went to this school’ — then suddenly you’re more willing to accept what they would recommend,” he said.

“Taking the surgeon out of the equation is not in the foreseeable future,” said Curt Doberstein, professor of neurosurgery at Warren Alpert and director of cerebrovascular surgery at RIH. “I see (AI) as a great aid to both patients and physicians, but there are just a lot of capabilities that don’t exist yet.”

Future of AI in medicine

With regard to the future of AI models in medicine, Asaad predicted that “the human factor will slowly be dialed back, and anybody who doesn’t see it that way, who thinks that there’s something magical about what humans do … is missing the deeper picture of what it means to have intelligence.”

“Intelligence isn’t magic. It’s just a process that we are beginning to learn how to replicate in artificial systems,” Asaad said.

Asaad also said that he sees future applications of AI in serving as assistants to medical providers.

Because the field of medicine is rapidly advancing, it is difficult for providers to keep up with new developments that would help them evaluate cases, he said. AI models could “give you ideas or resources that are relevant to the problem that you’re facing clinically.”

Doberstein also noted the role of AI assisting with patient documentation and communication to help alleviate provider burnout, increase patient safety and promote doctor-patient interactions.

Gokaslan added that “there’s no question that these systems will find their way into medicine and surgery, and I think they’re going to be extremely helpful, but I think we need to be careful in testing these effectively and using it thoughtfully.”

“We’re at the tip of the iceberg — these things just came out,” Doberstein said. “It’s going to be a process where everybody in science is going to constantly have to learn and adapt to all the new technology and changes that come about.”

“That’s the exciting part,” Doberstein added.