14 minute read

Long Live The King

BY T. EDWARD NICKENS

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust is working to ensure a sustainable future for Boca Grande’s iconic tarpon fishery through science-based habitat restoration.

It wasn’t all that long ago. Captain Ed Glorioso is only 39 years old, but he remembers the tarpon tournaments in Boca Grande, Florida, when anglers brought their dead fish to the old Miller’s Marina, and hoisted them up on the winches for photographs. He remembers the televised Professional Tarpon Tournament Series, started in 2004 in Boca Grande. It was ostensibly a catch-and-release tournament, but the intense competition and its televised nature made that lipstick-on-a-pig proclamation a joke. After the tournament, dead tarpon would wash ashore for days. And he remembers when the heavily weighted snagging jigs frequently used in Boca Grande Pass were outlawed, in 2013. Unfortunately, in the spring of 2024, a few anglers were still employing those deadly rigs, prompting Bonefish & Tarpon Trust to work with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to jump-start education and enforcement actions in Boca Grande Pass.

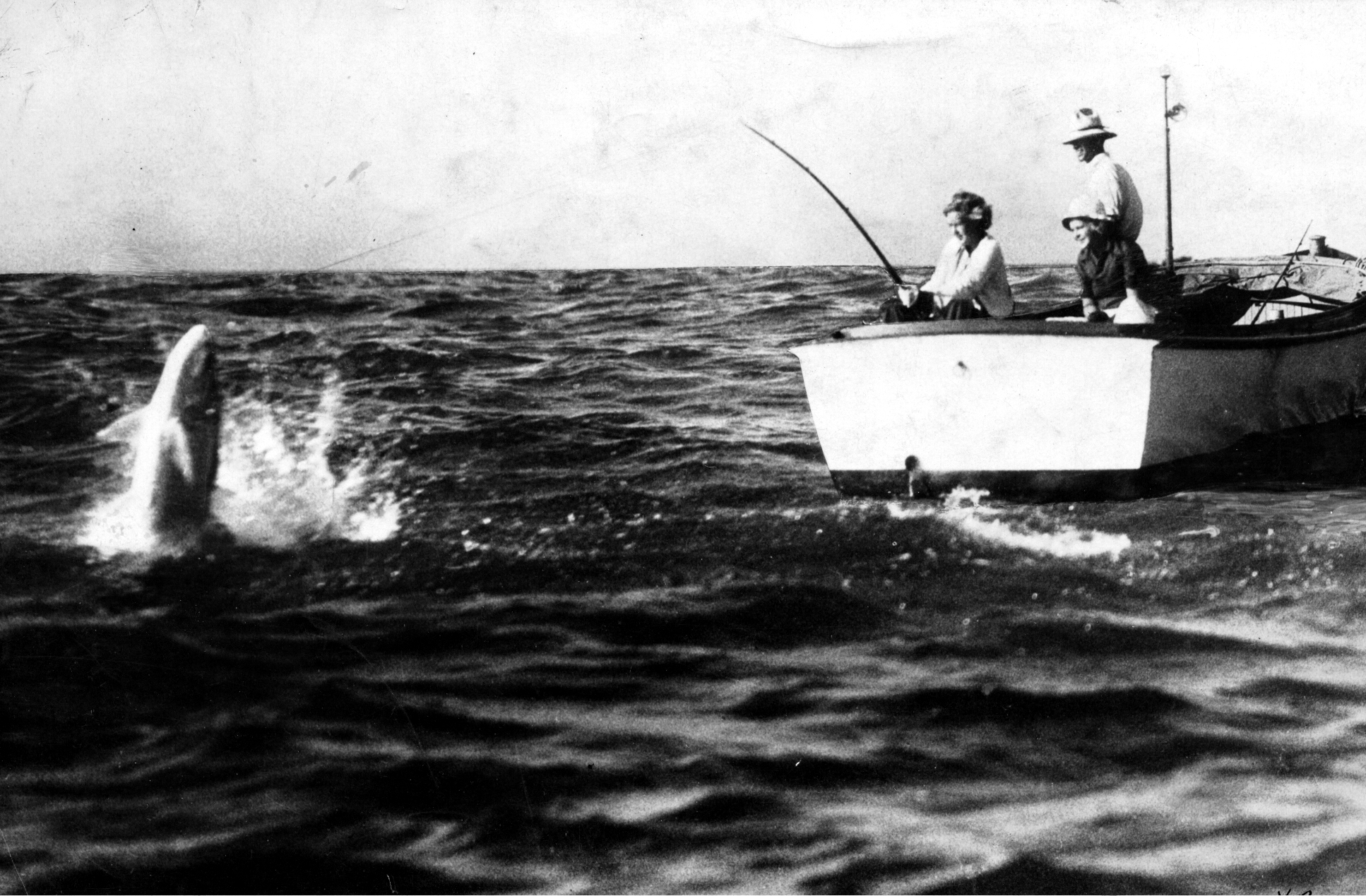

The stupendous tarpon fishery centered at Boca Grande Pass and nearby Charlotte Harbor has been the setting for unforgettable memories—both good and bad—for a very long time. Many consider the first tarpon caught on hook and line in Southwest Florida a 93-pound fish enticed with a live mullet and landed on a bamboo rod south of Boca Grande Pass in 1885, by an architect from New York City. In 1908 the stately Izaak Walton Fishing Club opened on Useppa Island, kicking off an era now heralded in cracked and faded photographs of anglers in dinner attire—men in bowties and white jackets, women in long high-collared Edwardian dresses—fighting leaping fish from canoes. One of the most impressive pageants of tarpon fishing in the region occurred in the mornings, when the steamship Valima departed from the 100-acre Useppa Island, towing a daisy chain of a dozen rowboats to Boca Grande Pass. Once in the inlet, customers gingerly stepped from the steamship to the rowboats, which were then untethered from the floating locomotive. When an angler stuck a tarpon, the guide’s first strategy was to row like hell for the Boca Grande Lighthouse, where the boats could be beached so the anglers could fight the fish from the sand.

And from then until now, the months of April, May, and June have served as a sort of tarpon angling zenith, when the fish can be caught, arguably, as easily and as accessibly as anywhere else in the world. Hundreds of boats crowd the Pass. Thousands of anglers are on board, and tens of thousands of migrating fish create countless memories.

It has been an astonishing century-and-a-quarter for the tarpon fishery in Southwest Florida. But two questions nag those who know the region’s tarpon fishery the best: What is it about Boca Grande Pass and Charlotte Harbor that have created one of the most distinctive and beloved tarpon fisheries in the world?

And is there a reckoning on the horizon?

Charlotte Harbor attracts tarpon—and tarpon anglers—for a simple reason: The estuary’s massive 270-square-mile-footprint includes much of the richest, most productive nursery areas for juvenile tarpon in all of South Florida. When they first arrive at Boca Grande Pass, there is nothing to suggest in a larval tarpon its ultimate power, or the astonishing size it might attain, or the hold it will have over grown men and women. The tiny tarpon are still in the leptocephalus stage, just a few transparent inches of wiggle and squirm, but they were born far offshore and show up with as many as a hundred miles on the odometer. Then, with Gasparilla Island to the north and Cayo Costa to the south, these fish-that-are-not-quite-yet-fish make a final push through one of the deepest passes on the Florida coast, under cover of darkness towards the labyrinth of estuary and tidal river and shallow marsh retreats of Charlotte Harbor.

And that’s where the going starts to really get tough. The primary challenge for the tarpon of Charlotte Harbor is that the places tarpon larvae and tarpon juveniles need to thrive are butted up against places where people want to live—or drive or shop or work. “These juvenile habitats are the ones closest to humans,” explains JoEllen Wilson, BTT’s Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Program Manager. And the threats are nefarious. In addition to outright habitat destruction, the changes brought about by disturbance of the landscape can have negative impacts far away. “Even if the regulations say you can’t build on the coast, but you’re building 100 yards from the line,” Wilson says, “that changes water flows and water quality. And impacts juvenile tarpon in significant ways.”

Compounding the challenge is that tarpon are such long-lived species, and don’t reach sexual maturity until they are seven to 10 years old. That creates a built-in time lag before problems with the health of juvenile tarpon show up in the adult population. “We don’t see the impacts of juvenile tarpon habitat degradation for 10 or more years down the road,” explains Dr. Aaron Adams, Director of Science and Conservation for BTT. “That means what we see in the water now is based on what was going on in those habitats 10 and 20 years ago.” The amount and quality of juvenile tarpon habitat is likely the most significant factor limiting overall tarpon numbers, Adams continues, which means that if we continue to lose habitat “we will continue to lower the cap of what is possible for the population size of tarpon in the future. What’s scary is that a lot of populations will remain relatively stable even as their environments degrade. But when you get to a certain point, they will crash. The problem with a fish like tarpon is that you don’t realize you’ve reached that threshold until you’re past it.”

Given its critical role in maintaining tarpon populations on a large scale, BTT centered crosshairs on Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande Pass as early as 2012, with studies on the life history of juvenile tarpon in the region. Scientists knew there were juvenile tarpon in water bodies such as golf course ponds and drainage ditches. What wasn’t known was whether those waters functioned as suitable habitats, says Wilson, who first started working with BTT in 2009 and transitioned to a graduate student focusing on those initial habitat studies. Were the young tarpon living in such human-impacted habitats able to immigrate back to open estuary waters, and when they were, were they in healthy condition for the rigors of making it out of Charlotte Harbor and through Boca Grande Pass?

Glorioso took part in some of the initial samplings of juvenile tarpon habitats in Charlotte Harbor. When Wilson first took him to waters she planned to monitor for juvenile tarpon, “I thought she was crazy,” Glorioso laughs. “She showed me this stuff, just mosquito ditches and little ponds, and I thought: This mess is stagnant. Nasty. You wouldn’t think anything would live in there.”

But plenty of juvenile tarpon did, which changed Glorioso’s perspectives of what is, and what could be, productive tarpon habitat. The protection of tarpon, he says, has to start when the fish are barely large enough to see. Tourists stay in hotels and rental homes, and drive over small bridges and recreate around golf course ponds and stormwater wetlands and “have no idea that’s where tarpon grow up,” he says. “I didn’t. But then I realized that if we keep filling these things in, then we won’t have any tarpon. So, these conversations have to continue, and fishing guides are in a great position to help educate the public.”

For BTT, moving forward in the Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande area meant moving from life history studies to hands on efforts to restore habitats. In 2016, BTT kicked off a Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Mapping Project, working with anglers to identify habitats that held tarpon less than 12 inches long. More than 65 percent of those reported ponds and wetlands were classified as altered or degraded versus remaining in a natural condition. To restore such damaged habitats, BTT worked with the Coastal and Heartland National Estuary Partnership, Southwest Florida Water Management District, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to design and test three different tarpon nursery habitat models in the Coral Creek Preserve north of Boca Grande Pass. By manipulating the depth of creek mouth openings, and the excavation of deep holes to provide a temperature refuge for fish, researchers have pinned down the specific design attributes that maximize juvenile tarpon production.

One of the reasons Charlotte Harbor has been such a fruitful location for studies—and such a critical population source for tarpon—is development in the area has been relatively low compared to much of South Florida. “But now the rate of development has accelerated dramatically,” Adams said, a situation that has energized BTT’s habitat efforts.

“It’s obvious that Florida is not going to stop developing,” says Malcolm “Mick” Aslin, a Boca Grande businessman who has been deeply involved with conservation efforts in the region. Aslin and his wife, Kathy, supported that initial graduate research for the first studies of juvenile tarpon habitat, and have remained steadfast champions of BTT’s evolving efforts to restore habitat in the watershed. “Given that reality,” he continues, “the question becomes how we find win-win solutions for the economy and growth and still have the wild things and an environment more beautiful and habitable for both humans and wildlife.” It’s not an easy task, and there are no workable pie-in-the-sky solutions. “At first I thought, oh, we’ll throw a little money at this for a couple of years, and see what we can do,” Aslin says, laughing wryly. “But I’ve learned that this is a process. You have to find a focus and stick with it. My perspectives as a supporter of conservation had to evolve along with the science and the habitat work.”

That evolution is showing promise across varied scales. While BTT continues its studies of habitat design in Charlotte Harbor, the organization is in the last lap of a multiyear project to restore more than 1,000 acres of mangroves in the Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, south of Naples. And BTT’s early juvenile tarpon habitat efforts have now matured to a program in which the most threatened habitats in the region are being classified in a way that land managers and conservationists can focus work on those habitats with the best chance of remaining, or returning, to a state of functionality. Funded by a NOAA RESTORE grant, BTT and its partners—Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Coastal and Heartland National Estuary Partnership and Charlotte County—are working to overlay known juvenile tarpon habitats with “threat maps” outlining public vs. private ownership, potential development plans, the flow of freshwater streams and creeks, and even potential disturbances due to sea level rise and storm vulnerability. Dubbed a “Vulnerability Index,” the work will take the guesswork out of next steps for tarpon conservation. Once such a matrix has been established for Charlotte County, BTT will take the template to other regions rich in juvenile tarpon habitat.

It’s been a remarkable 12 years for BTT’s Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Program in the Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande Pass region, with a zero-to-solutions trajectory: This is the problem. This is how to fix it. This is where to start.

And the solutions can’t come too quickly. Because the tarpon of 10, 20, and 50 years in the future are in the nursery habitats of Charlotte Harbor at this very moment.

One hundred years before JoEllen Wilson and Capt. Ed Glorioso first collected juvenile tarpon from the Charlotte Harbor estuary, A.W. Dimock published his epic tome, The Book of the Tarpon Tarpon fishing in Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande Pass have produced many a big fish story, but few can compare to one of Dimock’s tarpon tales, and a tarpon story with a lesson still relevant today. Dimock and his son, Julian, who he called “the Camera-man,” were fishing near Boca Grande Pass in a canoe when a six-foot-long tarpon engulfed a Spanish mackerel Dimock had reeled to the side of the boat. “…His shining, silvery scales grazed the side of the canoe as his great bulk shot six feet in the air,” Dimock wrote. An astonishing battle ensued.

Dragging the canoe behind, the tarpon headed first for Captiva Pass, then changed course and charged for Boca Grande Pass. “I could do nothing to check the fish,” Dimock wrote. “Gaily he traveled, with occasional frisky leaps in the air, for he was outward bound and rejoiced in the trouble preparing for us.” Each time Dimock fought the fish to the canoe, it surged anew. Once in the

The next generation. Photo: John Rohan inlet, an outgoing tide had stacked up breakers in the pass. Dimock had to let the line run more freely “that the canoe might quarter the crested billows.” Soon enough, he was out of line. The tarpon took it all, leaving Dimock and his son to fight swells in the inlet so tall they lost sight of land as the canoe sagged in their troughs.

Later that day, after the pair paddled back to their houseboat, Irene, the tide turned “and the incoming flow from the Gulf brought rolling porpoises, leaping tarpon, and hideous sharks through the now smooth waters of the treacherous pass.” Julian asked his father if he wanted to go in search of tarpon again.

“I quoted to him,” wrote Dimock, “’A sportsman stops when he has had enough,’ and told him that I had had enough for the day.” Even then, more than a century ago, the wisest anglers knew when it was time to give the fish a break.

If the future is to hold anything like the tarpon fishing of the present, much less the past, anglers will need to continue to give fish a chance. And our human societies will need to do the same with the habitats that tarpon require. Glorioso has seen the evolution in how anglers handle tarpon, from hanging them up for display, to not bringing them in to the docks but still pulling them halfway onto the boat, to now keeping their heads completely in the water. “Half the time I won’t even touch the fish,” he says. “I tell my clients—I’m grabbing this line for the release and you better have your camera ready. Because we’re letting this fish go and getting it back in the game in as healthy a condition as possible.”

Back in the game—that’s a fitting refrain for the work BTT is doing for tarpon in Southwest Florida. Boosting overall tarpon populations by restoring juvenile tarpon habitat is the only way to ensure that tarpon numbers don’t go off a cliff. “It’s like a recession,” Adams notes. “Economists can only say we’re in a recession after the fact. So, we know the cliff for tarpon is out there. And we’re working our butts off to reduce the speed at which we are approaching the edge.”

An award-winning author and journalist, T. Edward Nickens is editor-at-large of Field & Stream and a contributing editor for Garden & Gun and Audubon magazine.