11 minute read

The forest for the trees

There are many potential factors that motivate members to take money out of their SMSF. Heffron managing director Meg Heffron looks at some of the bigger picture items requiring consideration before any drawdown is made.

Often a decision has to be made to take a significant benefit payment from an SMSF. It could be motivated by circumstance, such as having to pay a death benefit, or could be entirely voluntary. In fact, it might even be brought about by concerns over the proposed Division 296 tax and a desire to ensure one’s total super balance is below the $3 million threshold trigger.

Further drawdowns from SMSFs can be more challenging when lumpy or illiquid assets are involved. So are there strategies that can be undertaken either before, during or after the event to deliver the best possible result for trustees?

A pension or lump sum?

Generally large withdrawals are paid firstly from accumulation interests and these will naturally be in the form of lump sums.

But pension accounts are a different matter. When withdrawing monies from a pension account, the member has a choice – should they take it as a lump sum or commutation or just a very large income stream payment.

One of the benefits of a partial commutation, of course, is it means the member gets back some of the transfer balance cap they’ve used in the past.

It’s tempting to think it doesn’t matter for someone who has already converted all their super to a pension, so they don’t need to worry about their transfer balance cap anymore and haven’t made contributions in years. But these days there are a few extra points to consider before ruling out a partial commutation.

Future contributions

The extension of contributions with no work test up to age 75 now means some people will make contributions late in life, long after they thought their contributing days were over. A common example we see in practice is those whose pension accounts don’t keep pace with increases in the general transfer balance cap. A pension that started at $1.6 million in 2020 may well have increased a little, let’s say to $1.7 million. But if that is the member’s only super and they are still under 75, there is scope for a large non-concessional contribution.

While it may be possible to make the contribution, it can only be converted to a second pension if the member still has some of their personal transfer balance cap remaining. Hopefully they have taken any large withdrawals in the past as partial commutations rather than just large pension payments. Remember, the general transfer balance cap is likely to be at least $2 million from 1 July 2025.

And downsizer contributions can obviously happen very late in life as you can never be too old to make one. Again, it is one thing to make the contribution, but ideally the member would also be able to convert it to a pension. That’s when having some of their personal transfer balance cap available will be helpful.

Inheritances from a spouse

Super inherited from a spouse can only remain in super if it’s in pension phase. Again, that means having as much as possible of the personal transfer balance cap available is a bonus. It allows the survivor to leave as much as possible of the deceased member’s super in the fund. Even if this isn’t the long-term plan, it might buy time to wind down the SMSF’s assets over several years.

Choice about how the benefit is paid

Finally, partial commutations can be paid by transferring assets, whereas pension payments must be paid in cash.

On the whole, our default position is for most clients to treat large payments as partial commutations if only to preserve some options.

Assets or cash?

Only lump sum benefits, either payments from accumulation accounts or pension commutations, can be paid in specie and some interesting issues arise when they are.

Don't forget cash is needed for other reasons

The SMSF trustee needs to withhold tax from some benefits. This applies in very few cases these days, but a death benefit paid directly to a non-dependant beneficiary, such as an adult child, would be a good example. If tax is to be withheld, the trustee will need to hold on to enough cash to execute this. It’s perhaps one of the many benefits of paying a death benefit to the deceased’s estate, that is, the fund trustee has no obligation to withhold tax and so the gross value of the benefit can be transferred to the estate. The executor then worries about the tax. In fact, within the estate, tax can even be paid from other assets entirely unrelated to the super benefit.

Remember also capital gains are taxable on any asset disposal. It doesn’t matter whether the SMSF sells assets to pay a cash benefit or transfers the assets in specie, tax will be paid regardless and the fund will need enough cash to make that payment.

Rules about in-specie payments

While there are many rules about the people and entities from whom an SMSF can buy assets, there are actually no similar restrictions when it comes to selling assets. The only rule that comes close is that assets classified as collectables must be independently professionally valued first. So it’s entirely possible to transfer any asset the SMSF owns as a benefit payment to the member or to a beneficiary or their estate in the case of death.

In fact, SMSF members can even direct the trustee to transfer an asset directly to another person or entity in settlement of their benefit payment. Consider an SMSF that owns a property. The members have decided to withdraw a large benefit payment and have agreed with the trustee the property will represent an in-specie payment. With the right paperwork, the members could direct that the property is transferred directly to their family trust rather than themselves personally. Or it could be transferred to just one of them even though both might be taking benefit payments.

The key is the paperwork. It is critical to specify the member, being eligible for a benefit payment, is instructing the trustee to pay it to someone else.

All the usual SMSF rules apply in terms of making sure the value used for the transaction is a genuine market value. Further evidence needs to be obtained to demonstrate this. The fact there may be no legal requirement to obtain an independent professional valuation doesn’t mean it isn’t a good idea to have one performed, particularly if the asset is large and doesn’t have an obvious market value. And if the asset is property, check in with your solicitor on what is required for stamp duty purposes.

Optimising tax exemptions

When it comes to SMSFs entirely in pension phase, different choices often have a profound impact on exempt current pension income (ECPI). This is particularly true when paying a large benefit will also result in realising capital gains. But even if that’s not the case, it pays to understand the rules when materially changing the profile of the fund.

A 65-year-old client who is the sole member of his SMSF recently proposed the following series of steps:

• start a pension with $1.9 million, say from 1 December 2024, leaving around $5.1 million of his $7 million super balance in accumulation phase,

• fully commute the pension in the subsequent few months and pay the money out of super, andfully commute the pension in the subsequent few months and pay the money out of super, and

• start a new pension and repeat.

His objective was to take a lot of money out of his fund quickly in order to ensure his balance was less than $3 million at 30 June 2025 in anticipation of not wanting to qualify for the Division 296 tax.

Not only did this present some tax avoidance concerns, such as whether he ever actually intended to commence an income stream or was the action simply a scheme to get some ECPI, but it was unnecessarily complex because he didn’t understand the ECPI rules.

A far simpler, more legitimate and in fact more effective strategy would be to:

• start a pension with $1.9 million and leave this in place while simply withdrawing the minimum pension payment over the year, and

• take a lump sum benefit payment, say $4 million, from his accumulation account immediately.

The key feature of ECPI the client missed is that when it’s calculated using the actuarial certificate method, as it would have been in this case, the same tax-exempt percentage will apply to all of the fund’s investment income during the year, regardless of when it occurs and regardless of how it comes about, that is, to withdraw large amounts from a pension or accumulation account.

This is one of the truly special benefits of an SMSF.

Assuming the pension was in place from 1 December 2024 and the withdrawal was made at the same time, the actuarial percentage is likely to be around 24 per cent for 2024/25. This means 24 per cent of any capital gains will be exempt from tax even though the sales were made to free up cash for drawing benefits from an accumulation account.

In fact, the order of events doesn’t matter either.

What if my client had already withdrawn large amounts from super in July, but didn’t decide to start a pension until now? Is it too late?

No. Let’s imagine he starts a pension in December 2024. This time, the actuarial percentage would be around 27 per cent for 2024/25.

Hence 27 per cent of any capital gains realised in order to pay $4 million out of super would still be tax exempt even though:

• the cash was used to finance a benefit paid out of his accumulation account, and

• the gains were realised at a time when the fund didn’t support any pensions at all.

The key lies in understanding how the actuarial percentage is calculated.

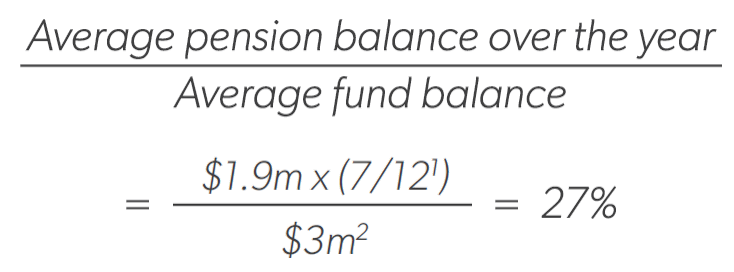

In this case, it is very roughly worked out as follows:

1 The pension would only be in place for seven months that year. 2 If the $4 million withdrawal is made at the start of the year, the fund would be around $3 million throughout the year.

Of course, this is oversimplified and makes no allowance for investment earnings, pension payments and the like. But it provides a reasonable guide.

Given this calculation, the same percentage applies to all investment income during the year no matter when the income is earned.

It’s slightly better than our first example even though the pension started at the same time in both cases. That’s because the average fund balance is lower this time – $3 million all year rather than $7 million for the first five months.

In fact, seeeing this client’s motivation was avoiding Division 296 tax, there’s another variation he could consider, that is, leaving both the sale of assets and subsequent withdrawal until July 2025.

If he did so, the actuarial percentage for 2024/25 would be much lower, around 16 per cent. But the percentage in 2025/26 would be around 63 per cent, reflecting the fact the $1.9 million pension would be in place for a full year rather than seven months and the fund balance would be around $3 million throughout. Not only would this mean much more of the capital gain would be exempt from tax, but his plans to avoid Division 296 tax wouldn’t be compromised as the critical date for his balance to be less than $3 million is 30 June 2026, not 30 June 2025.

There are, of course, many other issues to weigh up here, but if the primary driver is to minimise capital gains tax, this is an option worth considering.

Conclusion

As the SMSF population ages and many members spooked by the Division 296 tax are looking to draw down on their balances, we are likely to see large benefit payments made from time to time. It pays to think carefully about how to manage all aspects of the payment, such as managing ECPI, choosing whether or not to direct in-specie payments to other entities or people, thinking carefully about pension commutations and more.