10 minute read

To commute or not

The legacy pension amnesty was officially confirmed and approved late last year. Heffron managing director Meg Heffron analyses whether trustees should actually make use of the measure.

New regulations introducing a five-year amnesty allowing members with legacy pensions to wind them up was a welcome piece of news just before Christmas last year.

It’s difficult to get precise figures, but it seems there are still thousands of these income streams in place and I suspect many will be unwound in the next few years. Most will be market-linked pensions, also known as term-allocated pensions or TAPs. So is there anything we should watch out for as we’re happily commuting these? As always, yes.

First we need to make a quick distinction.

Most market-linked pensions started before 1 July 2017 and they’re known as capped defined benefit pensions. (As an aside, I do wonder who comes up with this terminology. Defined benefit has a specific meaning in superannuation circles and no market-linked pension is one of those. But I digress – capped defined benefit it is.)

Some people, however, have market-linked pensions that started on or after 1 July 2017. These are the people who used to have a pre-2017 market-linked pension, or certain other types of legacy pension, but have since stopped them and started a new market-linked pension.

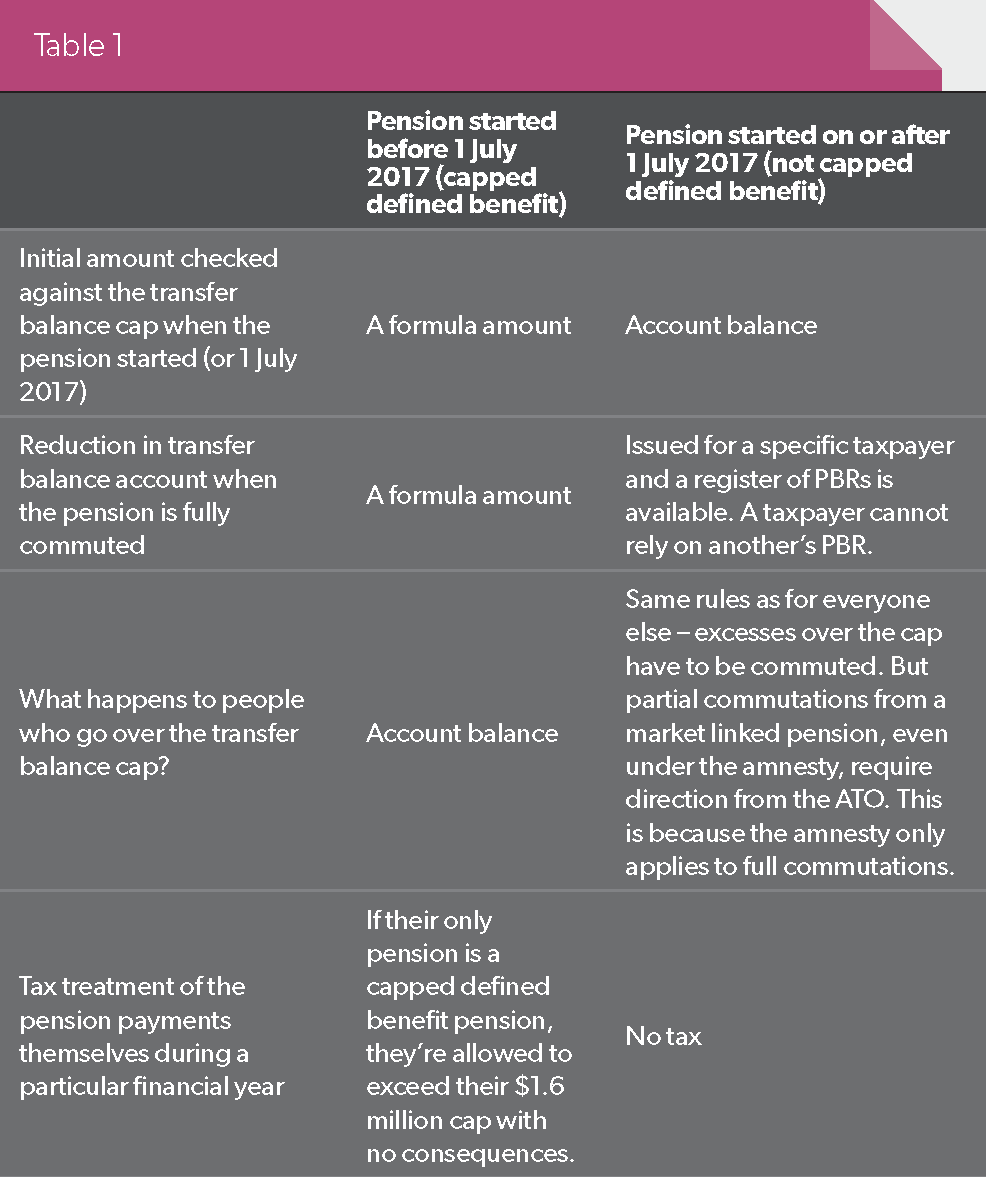

There are some important differences between the two that impact how easy they are to unwind today (see Table 1).

Can the full balance end up back in pension phase?

When it comes to capped defined benefit marketlinked pensions, the answer is often no.

It’s because of the special treatment, as explained above, these pensions receive for transfer balance cap purposes.

For example, Cliff, 82, has a capped defined benefit pension that started in 2006. Currently, the balance is $2.9 million and there are 19 years of his term left.

Back in 2017, the special value used for transfer balance cap purposes was $2.65 million. This was calculated using a formula at the time and didn’t have anything to do with his account balance.

If he fully commutes this pension today, the debit to his transfer balance account is not $2.9 million – his current account balance. Instead it is $2.65 million (the special value calculated at 1 July 2017) less all pension payments since then.

Let’s imagine Cliff has received $990,000 in pension payments between 1 July 2017 and today, including the full payment required for 2024/25.

His commutation value would be $1.66 million.

That means, even if he commutes his marketlinked pension, he has still used up $990,000 of his transfer balance cap ($2.65 million less $1.66 million).

Unfortunately, his cap is only $1.6 million. That’s because he used it all back in 2017, albeit he was allowed to go over it without consequence, so it hasn’t been indexed in the meantime.

So if he fully commuted his marketlinked pension, only $610,000 could be turned into a new account-based pension.

His SMSF would go from having $2.9 million in pension phase to only $610,000. That would make a big dent in the actuarial percentage used to work out how much of his fund’s income is exempt from tax.

A side note – you may have noticed the amount of Cliff’s transfer balance cap remaining ‘used up’, even after he fully commutes his pension, is exactly the same as the pension payments he’s taken since 2017. And in fact that’s a good rule of thumb to use for everyone – the amount of transfer balance cap used up by their (ex)-market-linked pension will be equal to the pension payments they’ve taken since 1 July 2017. This highlights another problem – people with very large market-linked pensions have often taken more than $1.6 million in pension payments in the last eight years. If they fully commute their market-linked pension, it won’t be possible to convert any of their super to a new account-based pension.

Would you still do it?

Maybe. Cliff’s market-linked pension payments, for example, in 2025/26, would be around $200,000. At that level the personal tax on his pension payments will be quite high if he’s paying tax at high marginal rates outside super. He might conclude it’s better to lose some of the tax exemption in his SMSF in return for lower personal taxes.

It’s interesting to model this over time to see which approach results in more tax.

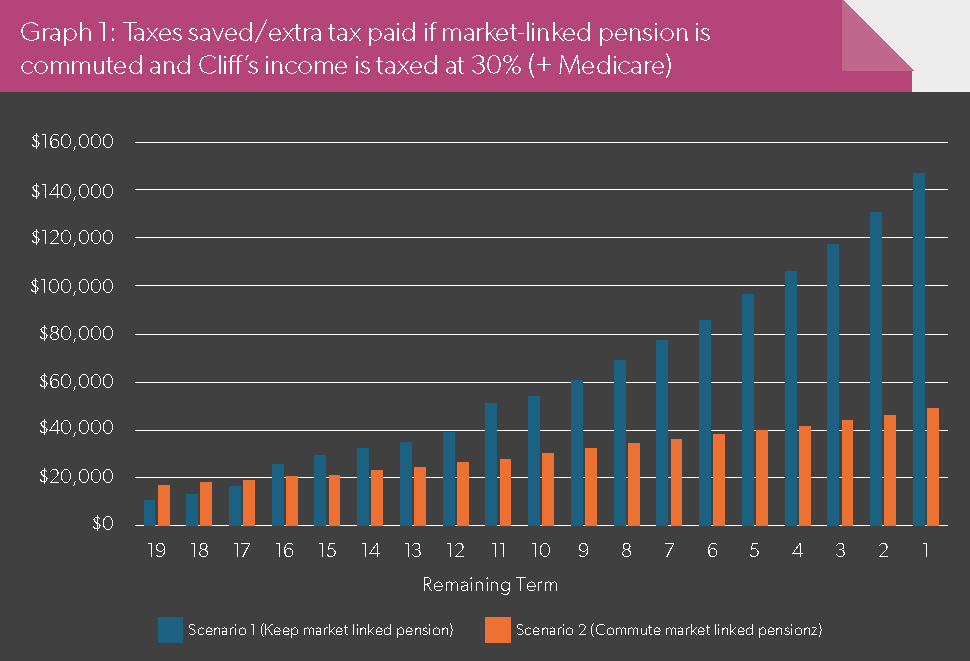

For example, if Cliff is already in the 30 per cent (plus Medicare) tax bracket outside super, the comparison looks as in Graph 1.

All the figures in Graph 1 are based on a yearly fund return of 7.5 per cent of which 5 per cent is income and therefore taxed each year. They have also been adjusted for inflation so the amounts shown at the end of the term are comparable to the amounts shown at the start. And finally, for now, we’ve completely ignored any capital gains tax that would be incurred if assets were sold.

The graph is showing what happens if Cliff fully commutes his market-linked pension and converts the proceeds to an account-based pension, valued at $610,000, and an accumulation account. To compare like with like, I have assumed that even if he does this, he will still withdraw the same amount from super each year made up of pension payments and withdrawals from his new accumulation account.

If Cliff does this, he will save a lot of tax personally, reflected in the graph as ‘personal tax saved (30% rate)’.

But his SMSF will pay more tax as per ‘extra fund tax (lost ECPI)’ (exempt current pension income).

If the personal tax saving was always much higher, this would be an easy decision – give up the tax break in the fund in order to reduce personal taxes, that is, commute the pension.

In this case that picture only starts to be clear later in the term. It’s because market-linked pension payments really tend to skyrocket as the pension nears the end of its term, at which point personal taxes are far more problematic than losing ECPI. In fact, at that point, even allowing for a large capital gain might not change the equation.

Cliff, of course, would find commuting his market-linked pension attractive for a host of other reasons. In particular, he would have a lot more flexibility. Not only would he have more freedom when it comes to choosing his pension payment amounts, but he would also be able to fully cash out his super if he got to the point where he was worried about death benefit taxes. In my experience, this is actually often the biggest motivator for people looking to exit their marketlinked pension, which makes sense as the people who have these pensions are often in their 80s.

But that begs the question: if commuting Cliff’s pension gives him more flexibility to draw more or less in pension payments, why have we assumed he won’t change anything on that front? In fact, with only $610,000 in pension phase, he could choose to withdraw far less from super.

If we allow for this extra factor, we can adjust the modelling a little. This time, we’ll have to think more carefully about what Cliff does with his pension payments. If different amounts are coming out of super, the simplest thing to assume is that he saves them all, effectively building up a non-super portfolio. A larger non-super portfolio will mean more personal tax, so this time we didn’t assume his tax rate stayed fixed at 30 per cent. Instead we assumed he had non-super yearly income of $30,000 and if he kept his market-linked pension, it would mean he would progress through the tax brackets as his pension income pushed his assessable income higher.

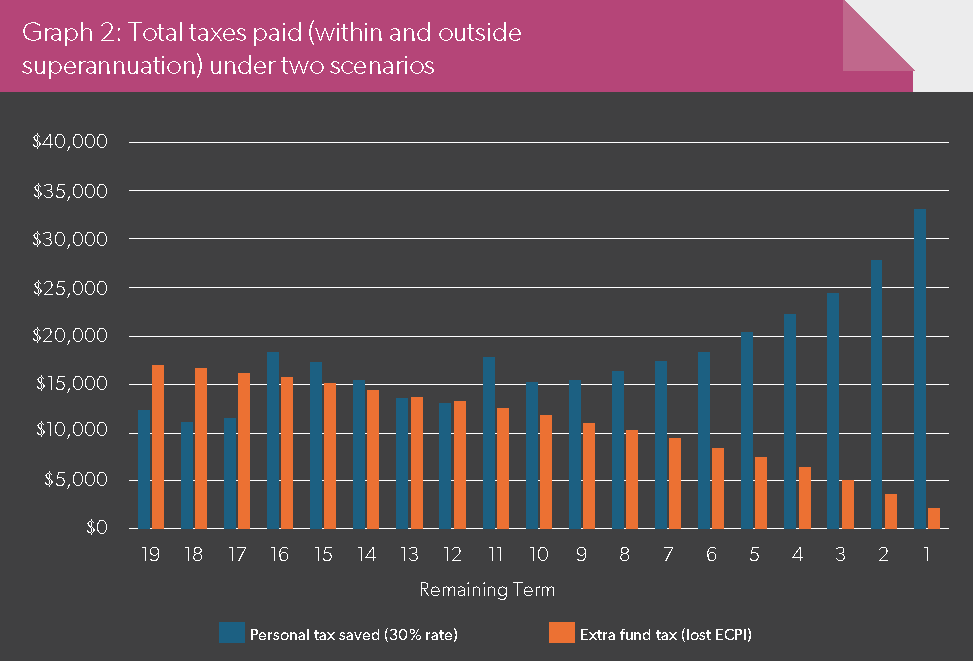

Graph 2 compares all the taxes each year under the two scenarios:

1. Keeping the market-linked pension (in which case he will have nothing left in super at the end of the term as all of his $2.9 million will have been transitioned out via pension payments), versus

2. Commuting the market-linked pension (in which case, the vast majority of his $2.9 million will actually still be in super by the nineteenth year. This is because most will be in an accumulation account and account-based pension payments tend to allow lower pension payments than market-linked pensions towards the end of the term).

Note, the tax amounts are each year rather than a total over time.

This time it feels a little simpler to make a decision. If Cliff really will leave as much as he can in super, commuting looks more attractive quite early on.

But bear in mind:

• there’s no allowance for capital gains tax. If Cliff realised a very large capital gain, say three years in, the total taxes paid under ‘Scenario 2 (commute market-linked pension)’ would jump, and

• it’s unlikely Cliff would really leave his super intact all the way up to age 100. He’d be worried about death benefit taxes.

Is it the same for everyone with a capped defined benefit marketlinked pension?

No. Cliff’s situation is extreme because he has a very long term remaining. If the term was much shorter, the ‘commute market-linked pension’ option would look much more attractive.

Things would also be different if Cliff’s SMSF was earning investment returns that involved more income and less capital growth as a greater level of income means additional tax now, so losing some of the fund’s tax exemption would cost more.

Cliff’s situation would also be quite different if he’d inherited this marketlinked pension when his spouse died a few years ago. Even if he inherited it after 1 July 2017, it remains a capped defined benefit pension because the pension itself started before that date. Remember inherited super can’t be left in accumulation phase. So commuting the market-linked pension under that scenario wouldn’t just mean Cliff had much less in pension phase, it would mean he had much less in super. Only $610,000 could remain in his SMSF and the rest would need to be paid out as a lump sum.

What about non-capped defined benefit market-linked pensions?

These are easy. All the complexity of formulae, et cetera, happened back when the original legacy pension was stopped and turned into a new post-2017 market-linked pension.

Today, fully commuting under the amnesty would allow any balance left in the non-capped defined benefit marketlinked pension to be converted to an account-based pension.

Conclusion

I still expect most clients, even those in Cliff’s situation, will commute their market-linked pension, but perhaps they will take it slowly. The amnesty lasts for five years and not everything needs to be done right now. If Cliff’s main driver for changing is that he wants to withdraw some but not all of his super entirely, perhaps he will look to sell down assets in 2024/25 and then commute the pension under the amnesty in 2025/26.