6 minute read

Mom's Photo Album

from BIPOC Lenses Issue 5

by bipoclenses

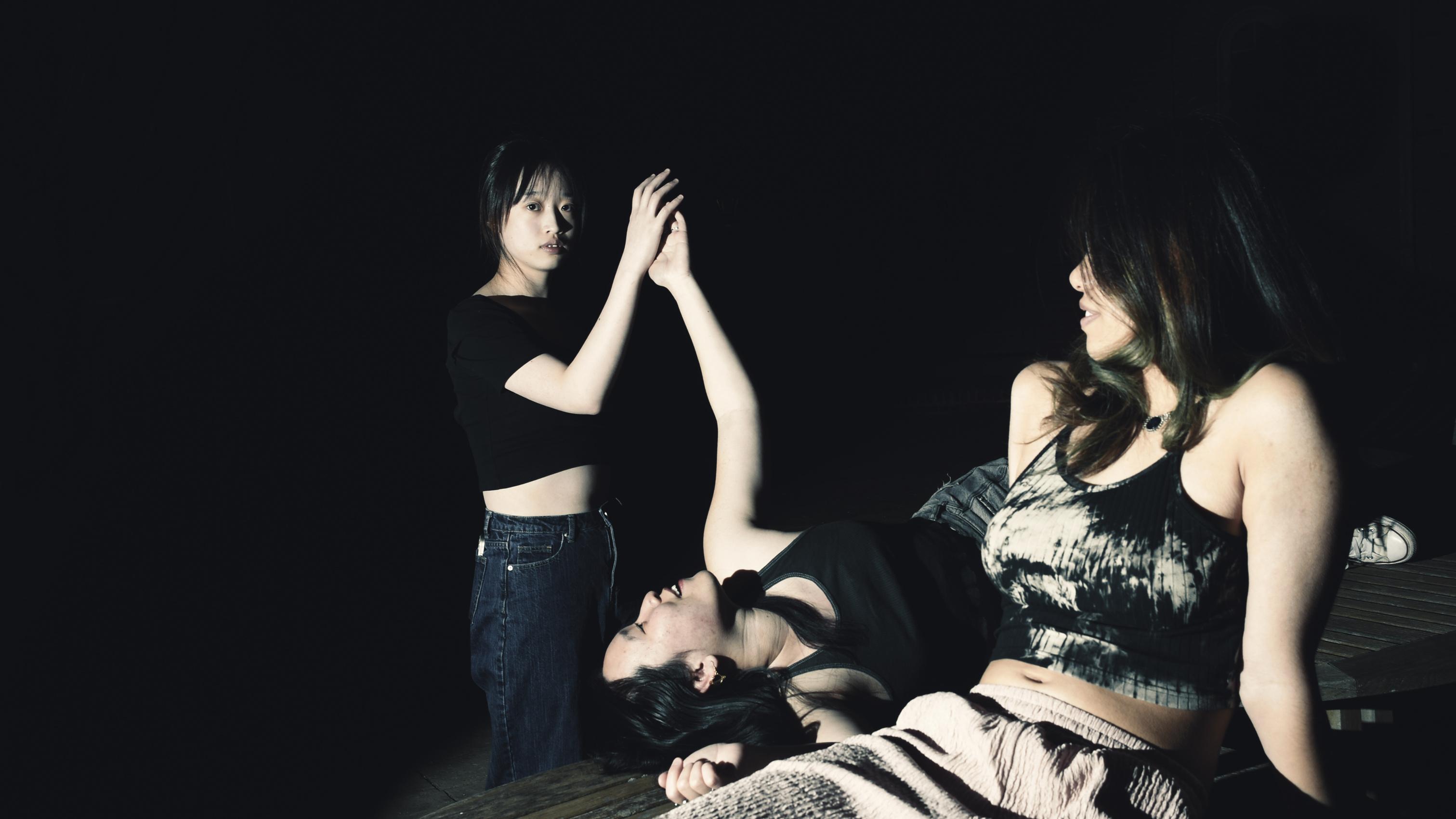

Sherry Miao

Approaching this topic through the film as an “outdated” photography method, I want to open discourse between two ages and generations. This project enabled me to have a deeper understanding of my mom. The arrangement of the photo album comes from my memory of my family photo album

Advertisement

Approaching this topic through the graphy ourse ations. have a y mom. to ory of

It’s weird to say that I was bilingual for two years of my life, but that’s exactly what happened At age 4 I could sing Korean Bible songs by heart and complete assigned grammar worksheets. At age 7 I had forgotten everything but the numbers 1-6, a few food items, and greetings My level of fluency has stayed the same since.

My relatives from the post-Korean war generation all have retained Korean at various levels, but my parents made sure to teach me, from buying Korean books to enrolling me in a predominately Korean preschool. Shortly after finishing preschool however, my family moved from to a 91% white town, and there were bigger problems to worry about than Korean When I first entered kindergarten, my parents thought I was selectively mute and almost held me back a grade because I literally didn’t speak to anyone at school for the first three months One time I couldn’t tell the teacher that I needed to go to the bathroom, had to get emergency clothes, and then needed emergency clothes for the emergency clothes because I was still too scared to ask Something stopped me from talking, from telling adults that I needed something and to other kids that I wanted to be their friend. Everytime I said something, I had to ask my mom if I was correct before one day she said “You know you don’t always have to check with me before

My Korean died a quick and uneventful death, my sound house(1) resembling an abandoned shed more than an actual house with the tools swiftly eroding away But despite my inability to speak, I didn’t mind I still enjoyed eating bulgogi, and going to family reunions in Seoul. I especially learned to love reading and writing in school – as I grew up, I experimented with flash fiction and poetry that will thankfully remain in some random folder in the deep deep abyss of Google Drive never to be seen again

One morning in sixth grade, my grandpa who lived in South Korea was hospitalized for a fall. My mom and her two brothers scheduled a time to meet, just once initially, and then maybe a check in after he got out of the hospital. One visit turned into two, then three, and then into a total of four years of on and off visits an ocean away Meanwhile, his condition deteriorated from fall complications to Parkinson’s and dementia As the oldest of three kids, I was put in charge, in my eyes, almost as the unofficial second mom

My own mom left at seemingly random times - ranging from Christmas to summer vacation to the time of an all-state chorus concert I was in Even though she was only gone for about 8-10 days every couple of months, it was difficult for me to adjust to. I felt a lot of emotions – fear about what would happen if she died in a plane crash, anxiety about how messy and disorganized I felt, jealousy of other kids who had two parents in their households at all times. But most of all, I was betrayed, by both my mom for leaving and my grandpa for forgetting. Eventually, I learned how to take care of myself and my siblings and work independently, in some way or another I made lunches for field trips, did my homework without asking for help, and remembered my sister’s after school extracurriculars so that my dad wouldn’t forget.

My grandpa died peacefully and alone in March 2018 The first memorial service was in Seoul, South Korea, the second would be in Iowa City, Iowa. While my mom flew out to South Korea to visit grandpa one last time, people from the 91% white town my family had once felt so alienated from raised enough money to hire a snow plow to clear out our house from a freak snowstorm so that we all had the chance to make it to Iowa City in time for the second memorial service and burial

A lot of things have changed since. I matured faster than others my age – sometimes I still refer to my younger siblings as “the kids” instead of as my actual siblings, even though there’s only a 3 and 7 year age gap respectively. When I was away from my family for a long time, whether it be a 6 week summer camp or college, I have never been significantly homesick But most importantly, it made me revisit my family’s collective sound houses and the tools we’ve had abandoned for so long in pursuit of things – education, societal pressure, assimilation Watching my mom with my grandpa in the hospital bed over FaceTime one Christmas Eve was almost a visualization of how quickly the language was dying in not only me, but my own family

Korean has been in slow decline within my family for a while. My great-great grandparents are the last generation to learn the language fully from childhood to adulthood When my great-grandpa was 10 years old, Japan annexed Korea and mandated Japanese as the primary language My grandparents and most of their siblings lived under the occupation until middle school/high school, and finally learned Korean after World War

II ended A couple years later however, my maternal relatives had to make the difficult decision to leave their village in what’s now North Korea, or stay behind and hope that the war would pass. Those who didn’t leave were never seen or heard from again, and the ones who did leave had to do so in dramatic fashion, such as rowing down the Han River for five miles or jumping out of a moving train. My grandpa, his siblings, and other family members who moved to the US for college and grad school ultimately settled around the Midwestern area, doing their best to provide for their kids and to fit in with American culture – I recall a story about my other grandpa who worked for over 40 years to try and remove his accent in English, to no avail

We have all forgotten a significant amount of Korean, and the language has effectively died within our generation. I was just one of many nails in the coffin. I’ve since moved onto focusing on school, studying for the ACT, getting into college, and now looking for a potential career focused on writing – in Standard American English. I’ve given up on the Korean language a long time ago. It is a language I love, but is something that will never be whole for me and now, nothing more than a language of regret

References

Lippi-Green, Rosina 2012 Lippi-Green, Rosina “The Sound House ” English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States,. 2nd ed. Milton Park: Routledge.

Author’s note: This was originally written for my Writing and Language Diversity class, in which we were to write a linguistic autobiography about ourselves. The title, in English, is “I don’t speak Korean and I’m sorry,” and it was run through Google Translate The Korean part, “한국어 못해요” , is probably the most important Korean phrase I need in order to communicate with other relatives and Korean people, yet one I can never remember I’m publishing this under my Korean name, the only thing I can write out in the language without assistance, in honor of what has been and what might have been.

This AAPI month, I am honoring the family members who I never got to meet – my relatives who were separated by the Korean War, my grandma who died two months before I was born, my great-uncle who died in elementary school. Their memories and stories have died in conjunction with my language loss. I’m sorry.

Rinse & Repeat

Beijing’s green space was, and remains, limited In the summer of 2011, the heat was stifling It baked down upon blocks and blocks of concrete, glass, and metal It ricocheted It emanated It was unrelenting Yet moments of relief could be found within the high walls of the Forbidden City. 姥爷 would walk alongside my ten year old self, his hands clutched firmly behind his back, leading me down a grey brick-lined path adorned with willow tresses. The tresses flowed in the occasional gasping breeze, causing them to beckon us forward Walk far enough and we’d eventually come across a vendor, before whom sprawled an assortment of mini red fishing poles I’d pick one, clutching the plastic handle in my ten year old hand, the other hand holding an immense mound of raw dough- bait for the goldfish And so it would begin: pinch a piece of dough between the thumb and index finger. Roll it into a ball. Spear it onto the metal hook, careful to not snag tender skin Drop hook into a deep basin of cool water swirling with red, orange, yellow patterned scaly bodies Feel a tug Pull a squiggling goldfish through the rippling water’s surface, up through the summer air, into the questionable safety of a water-filled plastic bag Like a shampoo ad, rinse and repeat, until bag becomes just like the basin of water below- swirling with red, orange, yellow patterned scaly bodies. And so began the treacherous bus journey back home- one hand holding 姥爷’s, the other determined to ensure the safety of my new goldfish friends And what a sight that was

Assistant Professor of Psychology Danielle Godon-Decoteau's research focuses on racism, culture, and mental health within Asian American Communities This interview serves as a way to examine her work's complexities and understand the impact of Racial trauma on POC identity