3 minute read

Connecting

124 SVA, NYU, Hartford University, RISD, and Princeton

SARAH I’d taught a class with Joseph in 1975 called “Theory of Art Workshop”. I loved teaching from the beginning. I loved it more and more and more. I’ve studied so much. I’ve read so much, seen so many shows, thought about art and thought about photography so much. Teaching is an opportunity to share that. I shouldn’t even say this—but it’s a little bit like mothering: you’re helping older kids figure out who they are and what they want to do. It’s a supportive role and it requires a lot of giving, but good giving; fun giving, rich giving.

MATTHEW C. LANGE Sarah was intimidating at first. She had a presence; you’d see her walking around the department with quite deliberate movements. There was a sense that you should have something important to say if you were going to approach her. She could be a little off-putting in terms of how direct she was. She would ask questions that would seem blunt, but she always had a good reason. You would hang pictures next to each other and she would say, “No. Absolutely not. You can’t do that!” Sometimes it was practical—“that one is orange and that one is a slightly different shade of yellow and it’s just not right.” Or sometimes it was, “The concept of this picture is totally at odds with the concept of the other.” Sarah was very careful and deliberate with her language. When a student talked about photographic tropes, Sarah said, “You’re not talking about tropes, but conventions—a convention is not the same thing as a trope.” She wanted students to choose their words, to weigh words as a way to clarify their ideas. Sarah believed that for your work to be successful, you should understand precisely what you’re doing. It goes back to her approach to making work, the connecting. It was always about asking, “How do these connect?” How can you bring these things closer to one another?” Always an insightful comment or an idea that would be incredibly productive. Her approach was rigorous, but done with very obvious concern.

CHARLES TRAUB Once Sarah connected, she was fiercely loyal. She always went to her student shows. She always remained loyal to her people—even if she fought them. “I don’t agree with you. I’m not gonna do it your way. But you’re still my colleague.” Her students were in awe because she was so unblinking about being an artist— being a well-known and important artist. She saw everything and she made her students do it. She would test you. “Did you see this show? What was it? Where was the so-and-so picture?” She was unabashed about addressing her opinion. I really admired her for that; we all did. Many times I would think, “She’s a pain in the ass. There is no give.” Then I would walk away and think, “Well, she might be right.” She had clarity of thinking. She was a very fine thinker.

MATTHEW C. LANGE After she was hired at Princeton, I was at Princeton, too. As we drove back to the city, there was always conversation about the student’s work and how their project was progressing. If somebody was not up to standard, or was faltering, Sarah was always very concerned. She’d see students on the edge of a good idea and wonder what she could do to help, to guide them toward making the work that they really wanted to make.

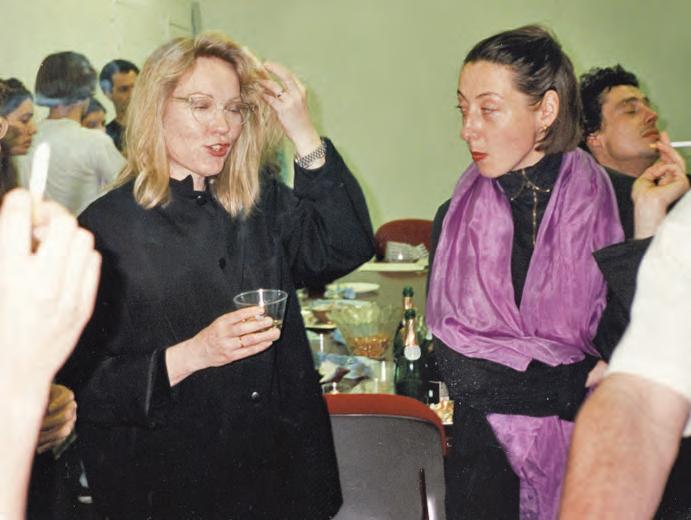

Sarah at SVA photographed with Vera Lutter. Sarah with Princeton class; April, 2013. Zwirner Gallery.

125