COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

2026–2027

Published by Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

Copyright © Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form including posting to the internet, photocopying, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Let us remember the wisdom they left for us to share, From our music and dance to the way we used to live

A shared gift from our Creator above us. The heart of our land where the river flows freely, And the wind blows through our mountains

A woven piece of art of the earth and sky

There lives the spirits of our ancient and wise ancestors.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

SUMMARY BACKGROUND

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Ancestral Vision and Leadership

Guiding Principles have remained the same for many generations:

“To preserve and protect our lands, tribal sovereignty, language, history, culture and the general welfare of the Nuchu.”

Don’t walk behind me; I may not lead.

Don’t walk in front of me; I may not follow.

Walk beside me that we may be as one.

— Ute proverb

The Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) contributes to effective economic development in America’s communities and regions through a place-based, regionally driven economic development planning process. Economic development planning – as implemented through the CEDS – is not only a cornerstone of the U.S. Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) programs, but successfully serves as a means to engage community leaders, leverage the involvement of the private sector and establish a strategic blueprint for regional collaboration. The CEDS provides the capacity-building foundation by which the public sector, working in conjunction with other economic actors (individuals, firms, industries), creates the environment for regional economic prosperity.

Simply put, a CEDS is a strategy-driven plan for regional economic development.

A CEDS is the result of a regionally owned planning process designed to build capacity and guide the economic prosperity and resiliency of an area or region. It is a key component in establishing and maintaining a robust economic ecosystem by helping to build regional capacity (through hard and soft infrastructure) that contributes to individual, firm and community success. The CEDS provides a vehicle for individuals, organizations, local governments, institutes of learning and private industry to engage in a meaningful conversation and debate about

what capacity-building efforts would best serve economic development in the region.

From the regulations governing the CEDS (see 13 C.F.R. § 303.7), the following sections must be included in the CEDS document:

n Summary Background: A summary background of the economic conditions of the region;

n SWOT Analysis: An in-depth analysis of regional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (commonly known as a “SWOT” analysis);

n Strategic Direction and Action Plan: The strategic direction and action plan should build on findings from the SWOT analysis and incorporate/ integrate elements from other regional plans (e.g., land use and transportation, workforce development, etc.) where appropriate as determined by the EDD or community/region engaged in development of the CEDS. The action plan should also identify the stakeholder(s) responsible for implementation, timetables, and opportunities for the integrated use of other local, state and federal funds;

n Evaluation Framework: Performance measures used to evaluate the organization’s implementation of the CEDS and impact on the regional economy.

BACKGROUND

The Ute were hunters and gatherers before European occupation. Destruction of this lifestyle began with the introduction of salt, flour and sugar, continued through the massacre of the buffalo, and was solidified as generations of Ute children were forced to attend boarding schools designed to break Indigenous family and community education systems and destroy the Ute language, culture and spiritual ways. This communal trauma also resulted in the devastating loss of traditional farming, harvesting and cooking knowledge, building nearly insurmountable barriers on the road to reclaiming food sovereignty and systemically increasing reliance on processed and prepackaged foods. The reverberations of these destructive policies are still felt today. Ute children of the Boarding School Era lost their connection to the Ute community and have raised generations of children who feel completely disengaged and without self-identity, making them vulnerable to drug abuse, domestic violence, diabetes and suicide. As a direct result of Indian Boarding School Era policies, poverty impacted an estimated 42% of UMUT children (more than double the rate in Colorado).

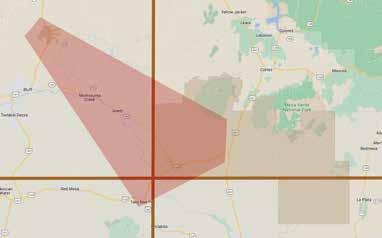

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is a small, proud tribe with approximately 2,100 members living on slightly less than 600,000 acres in Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. The tribal government center is located in Towaoc, Colorado, 15 miles west of Cortez and nearly 250 miles to the nearest major city. The majority of the members live in Towaoc, Colorado, with a smaller population of members living

on the reservation in White Mesa, Utah. The reservation land includes portions of New Mexico, but there exists no housing infrastructure in that state, as the Tribe was just officially recognized by the New Mexico State government in 2025.

In all matters, the Tribe is a sovereign nation and determines its own course of action. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council, subject to all restrictions in the Constitution and by-laws and the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, has the right and powers to oversee the following:

n Executing contracts and agreements;

n Engaging in business enterprise development;

n Managing tribal real and personal property;

n Negotiating and agreeing to tribal loans and financial instruments;

n Enacting and enforcing ordinances to promote public peace, safety and welfare.

The Tribe is structured as a Federal Corporation that may be used for business purposes in developing financial growth and the tribal economy. The fact that the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation lies in different states can add complexity relative to political dealings; however, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is a sovereign nation and has an agreeable relationship with the states. All tribal lands are trust lands, and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council has full authority and jurisdiction regarding all issues in the political geography.

TRIBAL COUNCIL

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) is a federally recognized tribe. The UMUT tribal constitution was adopted in 1940. The Tribe is governed by a sevenmember elected council, including a Chairman. One council member represents White Mesa and the other members are elected atlarge. The Chairman’s council seat is one of the seven seats elected through popular vote for a threeyear term. The position of Vice Chairman is held by an elected Councilman, selected every year by the Chairman. The Tribal Council Treasurer is an elected Councilman voted annually by the Tribal Council members. Current members and officers of Tribal Council are:

Selwyn Whiteskunk Chairman

Selwyn.Whiteskunk@utemountain.org

Gwen Cantsee Vice Chair/White Mesa

Gwen.Cantsee@utemountain.org

Kathryn Jacket Councilwoman

Kathryn.Jacket@utemountain.org

Marilynn House Secretary

Marilynn.House@utemountain.org

Tawnie Knight Councilwoman

Tawnie.Knight@utemountain.org

Conrad Jacket Treasurer Conrad.Jacket@utemountain.org

Alston Turtle Councilman

Alston.Turtle@utemountain.org

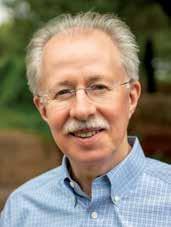

CEDS PROJECT LEADERS

bcascaddan@utemountain.org

BETH CASCADDAN

Dr. Beth Cascaddan, J.D., is an economic development strategist with over 40 years of experience in Indian Country, specializing in tribal governance, housing development, workforce development and enterprise creation. She currently serves as Director of Economic Development for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, where she leads strategic planning, enterprise development, workforce development, sustainable housing solutions and revenue expansion to strengthen economic sovereignty. She has a proven track record of aligning tribal governance, legal systems and economic enterprises to drive sustainable growth. Dr. Cascaddan’s career spans high-impact roles across law, business and community development. She has served as a Grant Administrator Analyst, overseeing compliance, fiscal processes, budget development and reporting for federal and state-funded programs. She brings additional expertise in human resources, training and workforce development from her tenure as People Lead with Walmart, where she recruited, trained and managed teams in a highvolume retail environment during COVID-19. Her career includes leadership in multi-million-dollar housing and infrastructure projects across the Navajo Nation, legal and compliance consulting for tribal governments, and corporate law management for international firms. Her work has been recognized with the Harvard Award for American Indian Governance and profiled in Who’s Who in American Law and Who’s Who in International Businesswomen. An enrolled member of the Métis Nation, Dr. Cascaddan brings a proven record of aligning legal expertise with economic vision to create lasting community impact.

BEVERLY SANTICOLA

Originally a farm girl from Indiana who learned how to drive a tractor, plant seeds and grow crops at a young age, Beverly Santicola has turned her agricultural childhood and lifetime work experiences into a purpose driven mission to grow a new generation of leaders for the future of Rural America. Beverly Santicola is social entrepreneur, capacity builder, problem solver, project facilitator and grant writing consultant. Over the past ten years, Santicola has focused her expertise and energy in the arenas of community development and collaborative partnership building for rural and indigenous people, including the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) in Colorado, New Mexico and Utah. Working with a team of professional grant writers that have generated more than ONE BILLION in grant funding for clients and more than $176 MILLION for the UMUT, she has been nationally recognized for social innovation and leadership excellence by the US Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, as well as Encore.org as a 2010 and 2014 Purpose Prize Fellow sponsored by the Atlantic Philanthropies and John Templeton Foundation. Beverly Santicola has helped the UMUT produce international award winning CEDS Plans since 2021, winning numerous Communicator Awards and Anthem Awards for excellence, effectiveness and innovation across all areas of communication, as well as global impact for mission-driven work. The Communicator Awards is evaluated by the Academy of Interactive & Visual Arts (AIVA), an assembly of industry leaders from acclaimed brands, institutions and agencies including PepsiCo, Accenture, NASA/JPL, FedEx, Netflix, Big Spaceship, National Geographic Society and more. Several federal agencies have suggested the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe CEDS should be the “gold standard” for all Native American Tribes.

bevsanticola@outlook.com

UMUT CEDS PLANNING COMMITTEE

Bernadette Cuthair Planning Director bcuthair@utemountain.org

Juanita Plentyholes Tiwahe Director jplentyholes@utemountain.org

Ronald Scott Chief Financial Officer rscott@utemountain.org

Lee Trabaudo UMUT Public Works/ Broadband ltrabaudo@utemountain.org

Dan Porter Kwiyagat Community Academy dporter@utekca.org

James Melvin Weeminuche Construction Authority jmelvin@wcaconstruction.com

Edwina Silas Economic Development Director edwinasilas@utemountain.org

Scott Clow Environmental Director sclow@utemountain.org

Patrick Littlebear Grants & Contracts Administrator plittlebear@utemountain.org

Marie Heart Staff Development Coordinator mlansing@utemountain.org

Miles Sturdevant Weeminuche Construction Authority msturdevant@wcaconstruction.com

Joe Lopez Weeminuche Construction Authority jlopez@wcaconstruction.com

Ben Elmore Weeminuche Construction Authority belmore@wcaconstruction.com

Brendon Adams Economic Development Coordinator brendonadams@utemountain.org

UMUT CEDS PRODUCTION TEAM

The UMUT CEDS Production Team has a reputation for producing award-winning publications. Last year’s CEDS Plan has been described by numerous federal agencies as the “gold standard for Native American tribes.” The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe 2025-2026 CEDS recently won three international Communicator Awards for Excellence in overall design, photography and strategic storytelling. The Communicator Awards is dedicated to recognizing excellence, effectiveness and innovation across all areas of communication. The Award of Excellence is the highest honor and given to those entrants whose ability to communicate positions them as the best in the field. The Communicator Awards is sanctioned and reviewed by the Academy of Interactive & Visual Arts, an invitation-only group consisting of top-tier professionals from acclaimed media, communications, advertising, creative and marketing firms.

MARC SANTICOLA | UMUT CEDS EDITOR

Marc H. Santicola is a retired financial/accounting executive with over 40 years of experience in manufacturing and the energy industry. He held various Controllership and Director of Finance positions with Fortune 500 companies (Schlumberger, Cameron International, Cooper Industries, Smith International) at the corporate, divisional and plant levels working in executive leadership, project management, financial planning, systems implementation, organizational restructuring and divestiture. Marc holds a MBA degree from the University of Pittsburgh and is now working as a consultant with NeoFiber on the Tribe’s $40 million Broadband Initiative.

AMANDA SHEPLER | UMUT GRANT WRITER

Amanda Shepler has more than seventeen years of grant writing experience working full time with a wide variety of clients including tribal governments, school districts, institutes of higher education, charter schools, municipalities, community-based agencies and more. She has personally won more than $100 million in grants and assisted the Santicola & Company team to win over $1 billion in grants. Amanda earned a Master’s Degree in History from Buffalo State College in 2006 and Bachelor of Science in Social Studies Education in 2003. Past work experience includes substitute teacher (2 years); Program Coordinator of Boys and Girls Club (8 years); President of Kiwanis of Tonawanda (2 years); and Board Member for Boys and Girls Club of the Northtowns (2 years).

ERWIN HANDOKO | FUND DEVELOPMENT RESEARCHER

Erwin Handoko works with Santicola & Company as a research associate. He provides prospect research weekly for Santicola & Company clients. Dr. Handoko is a former Program Manager and a lecturer for the Graduate Programs for Health Science Educators in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Houston. Dr. Handoko worked with the students in the Master’s and Executive Doctoral programs to provide support in designing, developing, delivering and evaluating multimedia-rich instructional materials for academic healthcare professionals. He also provides individualized consultation to the students to assist them with the research methodology of their doctoral theses. As a Fulbright scholar with more than five years of experience in the field of Curriculum and Instruction, he specializes in learning technologies, educational multimedia, teaching strategies and instructional design in online, face-to-face and blended contexts.

ANTHONY TWO MOONS | PHOTOGRAPHER

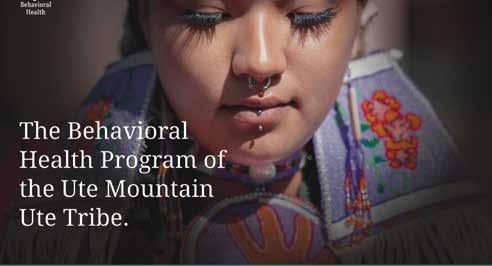

Anthony Two Moons is an Indigenous artist and photographer of Arapaho, A:Shiwi and Diné lineages. Following his studies, he started his career in New York City as a fashion photographer, and continues today as a photographer and director based in New York and working everywhere. His work has appeared in publications around the world. He is the author of multiple award-winning books, including Growing Ute: Preserving The Language and Culture, volumes 1 & 2, and Wíssiv Káav Tüvüpüa (Ute Mountain Lands). Anthony recognizes the extraordinary privilege and abundance of knowledge he has gained while working with talented individuals throughout his career. As an Indigenous professional photographer and artist, equity plays a vital role in Anthony Two Moons’ work.

LEEANN NELSON | GRAPHIC DESIGNER

LeeAnn Nelson has been an independent graphic designer since 1992, working for a variety of clients large and small across an array of industries including financial lending institutions, city governments, book and magazine publishers and a variety of nonprofit organizations. She holds a degree in journalism from Pepperdine University and before launching her freelance business served as Creative Director for a San Francisco, California, based magazine publishing company, producing six magazine titles per month. Her design work has earned accolades from the AJAP Simon Rockower Awards, the Maggie Awards, the Anthem Awards and most recently from the Communicator Awards for the CROPS 2023-2026 CEDS for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe.

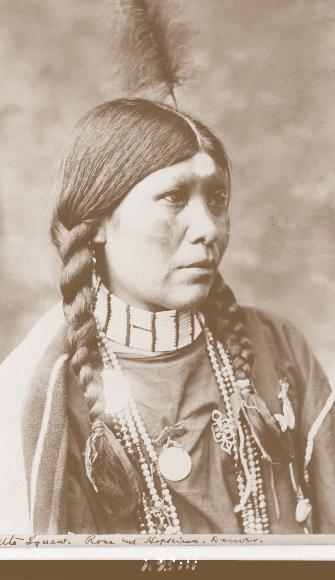

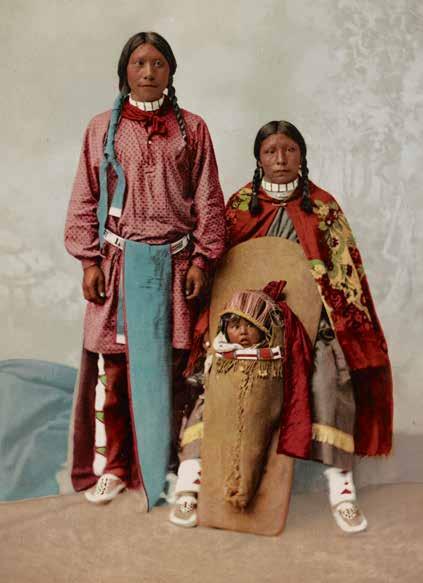

Five Ute women, c.1899, Library of Congress.

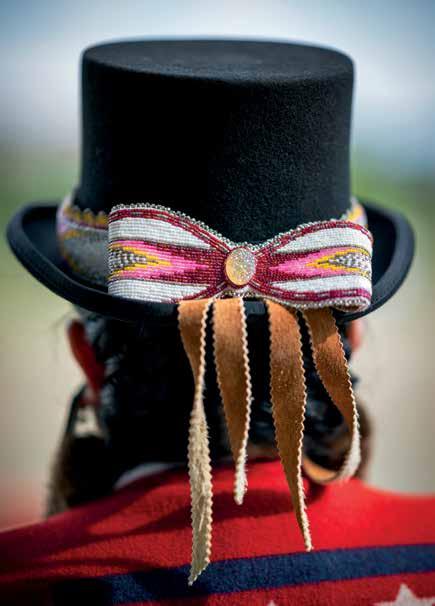

ON BEADING...

Cedar and medicine bags were created most often

To carry our belongings and needs. A woman’s first work of art must be given to an elder.

Our moccasins always took the longest to be made And we used the long winters for it So we could return to dance with them.

— Kamea (Mia)

Clark

PROGRESS AND NUCHU: PLANNING OUR VISION

The Ute (Nuchu) are proud and resilient people. They have an intimate knowledge of the land and a strong connection to their ancestors. An unbridled spirit and optimism drive them to address the challenges they face utilizing the assets, resources and power they have as a community. Societal challenges facing the region are serious and require systems-based responses.

To proactively seek partnerships and funding to address deep-rooted economic and social challenges, UMUT hosted the first-ever Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Native National Partnership Retreat in 2015, called Walking in Our Moccasins. It brought state, federal and private funding partners together to understand the comprehensive needs of the Tribe and help refine tribally designed solutions to align with current funding opportunities. Forty funding partners attended the event, and UMUT has leveraged their active participation into more than $170 million in new grants over the past nine years.

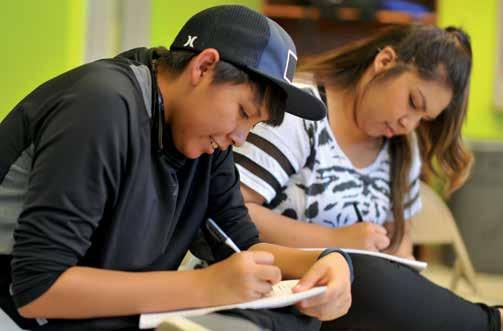

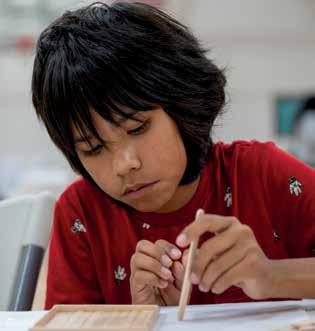

In 2021, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe established Kwiyagat Community Academy, the first public school operating within tribal boundaries since the 1940s, reestablishing local sovereignty over the education process and ensuring children will learn the Ute language, traditional skills and Indigenous knowledge in the classroom. Kwiyagat Community Academy offers opportunities for young generations to rediscover and recapture the storied histories of the past; understanding this disappearing cultural knowledge is critical to a prosperous future. Kwiyagat Community Academy is beginning the important work of healing the wounds caused by policies of the Indian Boarding School Era, providing cultural learning opportunities for school children in multi-generational environments.

Alongside efforts to reclaim educational sovereignty, UMUT is working to address the catastrophic impact of the loss of food sovereignty and the forced dependence on highly processed prepackaged foods.

If you have funding opportunities that could help meet the needs of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe please contact:

Bernadette Cuthair Planning Director bcuthair@utemountain.org 970-238-0129

Beverly Santicola Grant Writer bevsanticola@outlook.com 281-224-1443

Beth Cascaddan Economic Development Director bcascaddan@utemountain.org 970-238-0892

Until 2025, there were no stores selling groceries on the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe lands. The entire reservation, including both Towaoc and White Mesa communities, are USDA-recognized Food Desert Low Income and Low Access regions without ready access to fresh and healthy food choices.1

The nearest large grocery store is over 20 miles away. High rates of intergenerational poverty leave many tribal members without reliable transportation in a rural and remote community without public transportation options. Too often, when individuals secure transportation to a store, the nutritional value of selections is sacrificed for the extended shelf life of processed and packaged options. The community has been working on establishing a locally owned grocery store for several years, and business planning efforts are underway.

With at least 11% of UMUT adults diagnosed with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes and approximately 36% of children under the age of 14 diagnosed with prediabetic conditions, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

1 www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/go-to-the-atlas/

is still experiencing the effects of settler colonization. Although across the United States, life expectancy is reported at 78 years, on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, the average life expectancy is reported at just 55 years, more than two decades less than the national average.

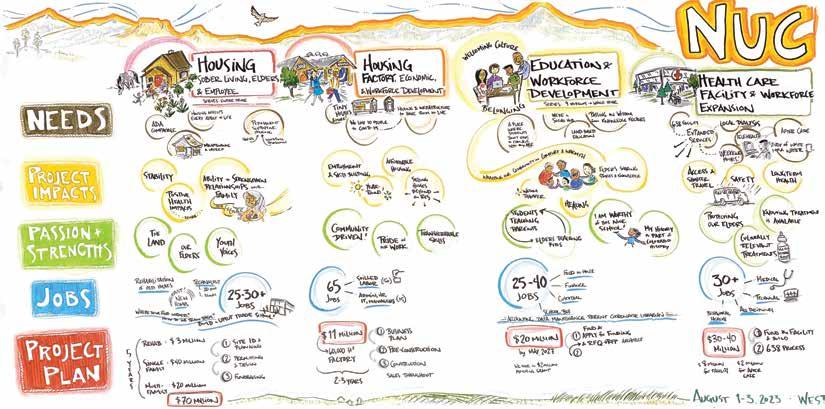

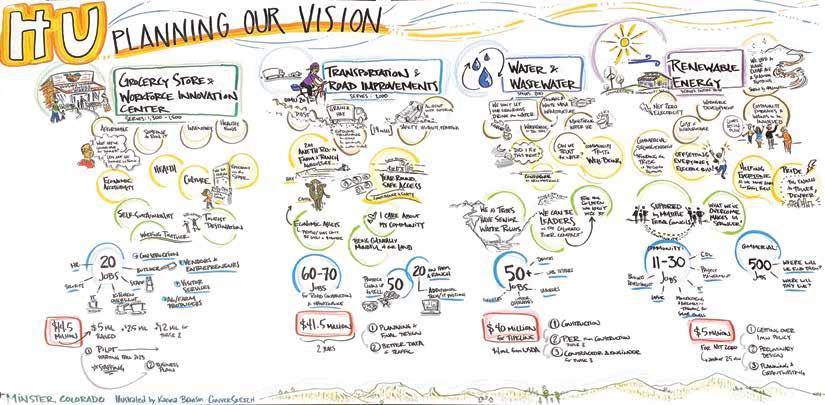

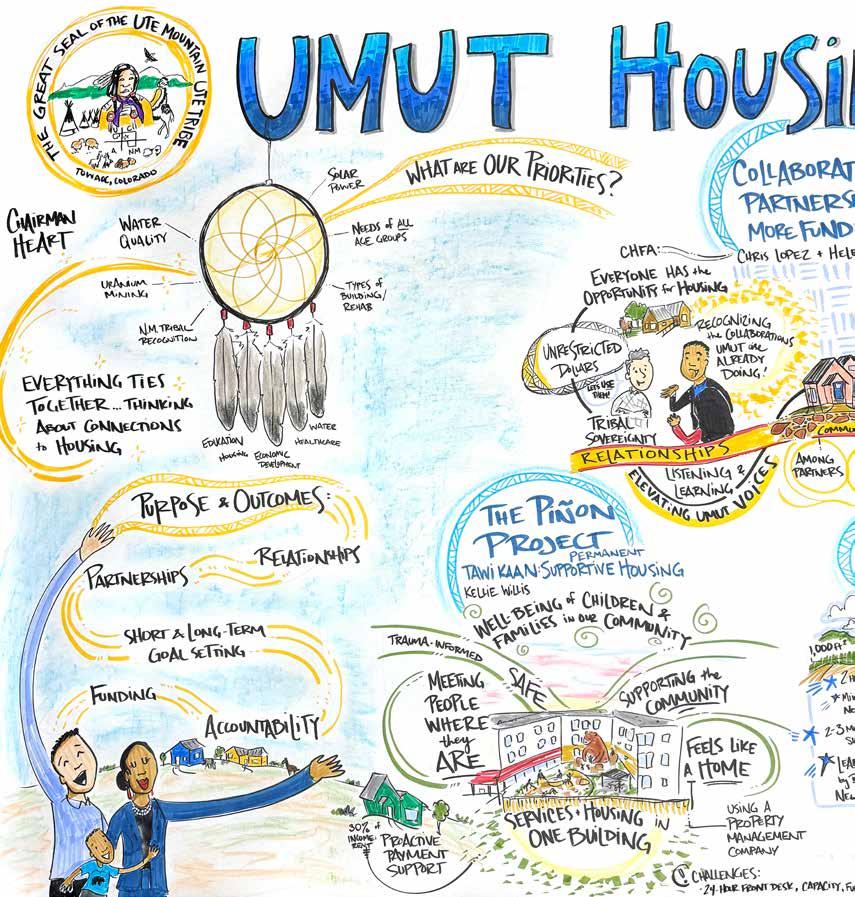

As recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic continued to realign priorities and needs, it was time again to meet and coordinate with state, federal and private partners at the Tribe’s second Native National Partnership Retreat, called Nuchu: Planning Our Vision. The event was held in August 2023, with over 50 funding partners in attendance. The two-day event allowed UMUT leadership and tribal members to explain current priorities and potential strategies. Together, the assembled group of tribal representatives, funding partners and consultants brainstormed opportunities to sustainably blend need and opportunity while honoring and respecting tribal culture and traditions. UMUT hopes to generate $240 million in new funding over the next five years as a result of this important work.

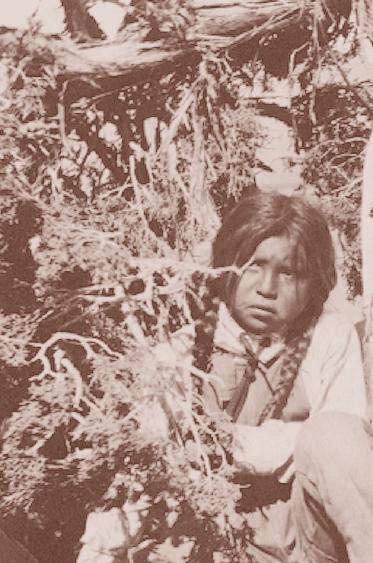

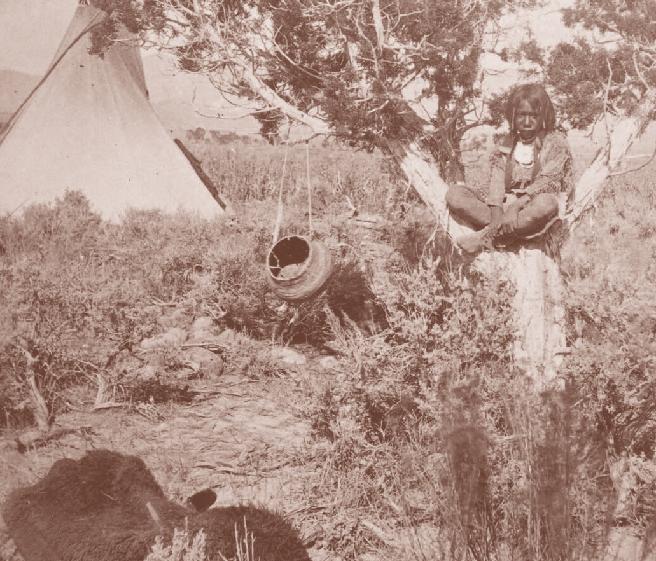

ON HUNTING...

We used to roam most of the earth and build our tipis and wickiups, Hoping for better seasons of food and weather.

Our men to hunt and learn the skills of hunting and language, And gives his first kill to an elder to give thanks. He takes out the heart of the animal and prays for blessings.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

In the days we used to live, Wild onions and yucca plants were sources of food. We boiled leaves and flowers for tea And ashes of them for juice. Wild chokecherries and buffalo berries were always picked And sourced for a special snack to ease our hunger.

Our sage used for healing and blessings To keep negative energies away and protect us From any harm in our bodies and minds. For our family is sacred and must be kept safe, We ask for forgiveness, health, and protection at all times.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

REGIONAL ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, COLLABORATION

AND COORDINATION

Located in the Four Corners Region of Colorado, Montezuma County residents have a median household income of roughly $50,717. This is more than $22,000 lower than the Colorado statewide median income of $75,231. Members of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe experience an even lower median income of $27,656. Montezuma County’s largest industries by employment are government, health services, retail trade and tourism accommodation.

CONDITIONS

Montezuma County struggles with some of the lowest enrollment in high-speed internet services in the state. Tribal communities are particularly impacted, which limits economic opportunities, including participation in remote work, and restricts educational attainment.

Increasing its overall isolation, the community is in a remote corner of Colorado without convenient access to major transportation highways, airports or rail lines, which further inhibits economic opportunities.

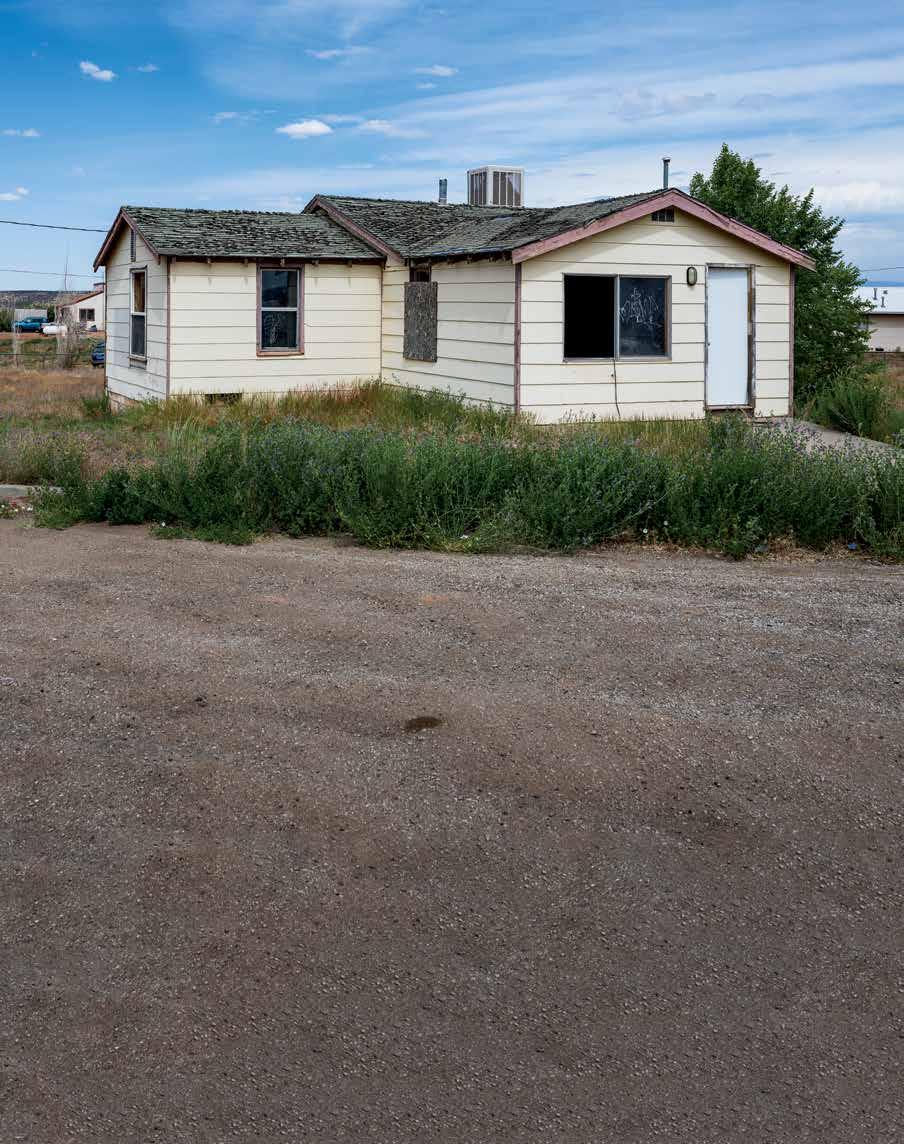

The Four Corners Region is experiencing a crisis of housing affordability and availability. The cost of living has been historically low and the population relatively stable in southwestern Colorado, but housing costs skyrocketed during the pandemic due to an already restricted housing supply and lack of scaled new housing construction. These conditions were met with buyers seeking affordable second homes for recreation and

investment. The lack of housing options plays a challenging role in recruiting businesses to the region and attracting a skilled workforce.

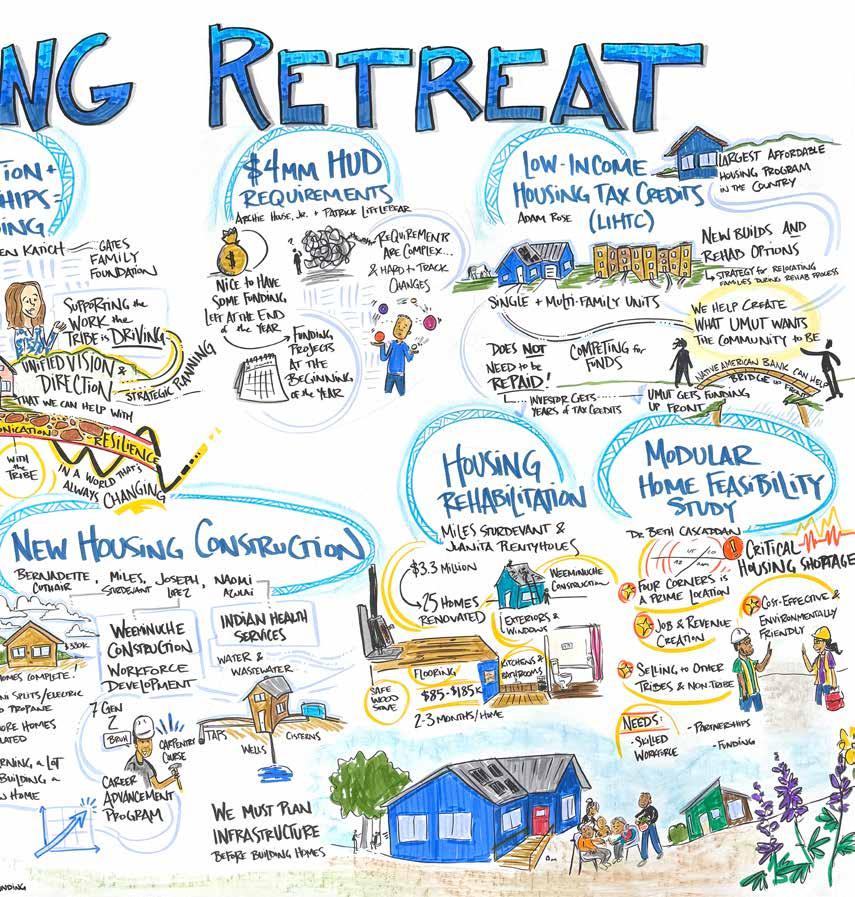

Housing on the reservation is constructed and passed on between families, so it does not benefit from typical marketbased values for housing construction. The tribally owned enterprise Weeminuche Construction Authority has been able to leverage limited grant dollars for housing rehabilitation and construction programs, but overall funding for a large housing development has not been available for the over 200 families waiting for new housing.

Compounding the previously mentioned economic vulnerabilities, there are social and environmental factors, including extreme drought driven by climate change, drug use and mental health challenges, and historic barriers to civic engagement by tribal members that create additional challenges to the region’s workforce and future business growth and opportunities.

COLLABORATION AND COORDINATION

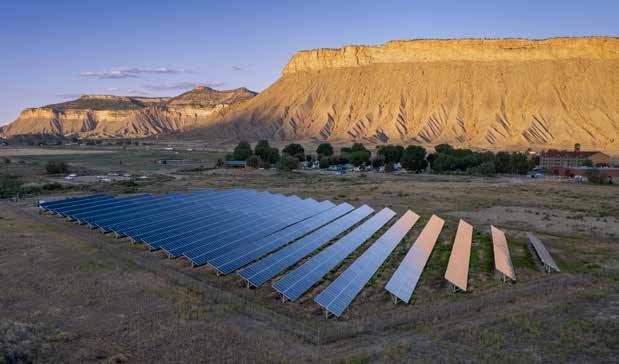

The UMUT is currently constructing broadband infrastructure across the reservation and Montezuma County with the support of nearly $40 million in federal and state funds. A long-term goal of the initiative is to create future revenue for the Tribe through connection leases. With expanded broadband infrastructure, business support services and workforce training are an opportunity to increase immediate economic opportunities with members of the Tribe.

As an owner of over 550,000 acres of land in Colorado and New Mexico, the UMUT has been exploring opportunities to recruit new businesses to the reservation, including potentially constructing a modular housing factory and also drawing tourism dollars utilizing the cultural, historic and natural amenities for outdoor recreation in the region.

The southwest region is starting to recognize and grow culturally aware and responsive leadership that better understands the historic implications of mistreatment of Native people. New rising leadership in the area’s county government, school groups, health care organizations and Region 9 Economic Development Region has demonstrated an opportunity for improved collaboration and resource sharing that respects the culture and expertise of Native people.

The state of Colorado and private funders have been increasing investments in affordable housing solutions across the state. With the support of organizations like the Colorado Health Foundation, the Colorado Division of Housing and the Colorado Housing and Financing Authority, the UMUT has been able to incrementally and successfully fundraise several million dollars to support housing rehabilitation to revitalize existing family housing and build the groundwork for future housing investment.

SWOT ANALYSIS

“My grandfather said that this land was the center of the universe.”

— Aldean Ketchum, White Mesa elder, 2023

STRENGTHS AND OPPORTUNITIES

LAND

Historically, the people of the Ute Nation roamed throughout Colorado, Utah, northern Arizona and New Mexico in a hunter-gatherer society, moving with the seasons for the best hunting and harvesting. In the late 1800s, treaties with the United States forced them to move into southwestern Colorado. Currently there are three Ute tribes — the Northern Ute Tribe in Northeast Utah, the Southern Ute Tribe in Southwestern Colorado and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) in Montezuma County (Towaoc), Colorado, and San Juan County (White Mesa), Utah.

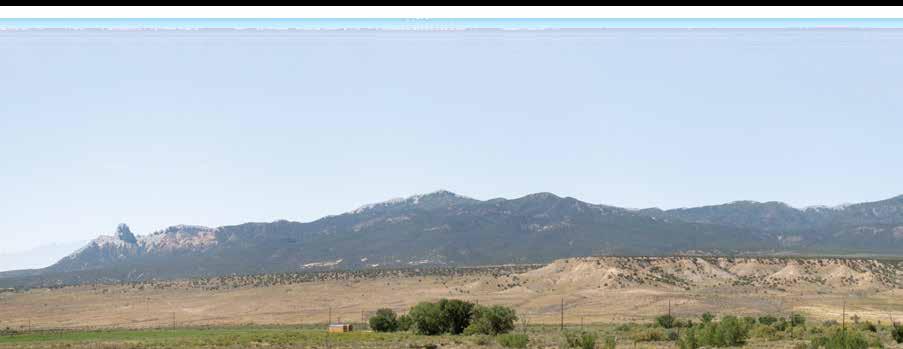

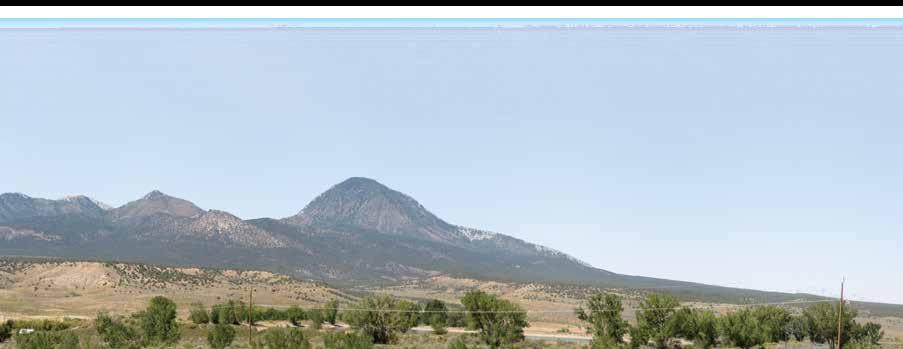

The UMUT people have lived on this land for over 100 years. Today, the homelands for the Weeminuche, or Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, are slightly less than 600,000 acres. The tribal lands are on what’s known as the Colorado Plateau, a high desert area with deep canyons carved through the mesas. Towaoc is located southwest of Mesa Verde National Park and northeast of scenic Monument Valley.

In addition to the land in Colorado and New Mexico, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe also has a presence in southeastern Utah on allotted trust land. These lands, or allotments, cover 2,597 acres and are located at Allen Canyon and the greater Cottonwood Wash area as well as on White Mesa and in Cross Canyon. Some of the allotments in White Mesa and Allen Canyon are individually owned and some are owned by the Tribe as a whole. The Allen Canyon allotments are located twelve miles west of Blanding, Utah, and adjacent to the Manti La Sal National Forest. The White Mesa allotments are located nine miles south of Blanding, Utah. The Tribe also holds fee patent title to 41,112 acres of land in Utah and Colorado.

Tribal lands also include the Ute Mountain Tribal Park, which covers approximately 125,000 acres of land along the Mancos River. Hundreds of surface sites, cliff dwellings, petroglyphs and wall paintings of Ancestral Puebloan and Ute cultures are preserved in the park. Native American Ute tour guides provide background information about the people, culture and history who lived in the park lands. National Geographic Traveler chose it as one of “80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century,” one of only nine places selected in the U.S.

National Geographic Traveler chose the Ute Mountain Tribal Park as one of “80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century,” one of only nine places selected in the United States.

Topographically, the UMUT Reservation is characterized as a high desert plateau, with the elevation ranging from 4,600 feet along the San Juan River to 9,977 on Ute Peak. Vegetation ranges from sagebrush shrubs in the lower elevations to ponderosa pine forests in the higher elevations. The reservation includes six vegetation zones, including semidesert grassland, sagebrush savanna, pinyon juniper woodland, mountain, chaparral and ponderosa pine-fir-spruce-aspen. Approximately 3,800 acres of noncommercial timber forests are represented in these vegetation zones. The reservation contains verified or potential habitat for several federally listed species of plants and animals.

Reports indicate that the Ute Mountain Ute land, as late as the 1870s, contained grasses, harvestable as hay in non-wooded areas, with sagebrush sparse or absent. This condition was changed by heavy grazing, in part due to encroachment from non-Indian livestock. Overgrazing resulted in serious range depletion, with invasion or increase of sagebrush and other undesirable species, the cutting of gullies and arroyos in the lowlands, and severe erosion in the uplands.

Later reductions in livestock numbers have resulted in partial recovery of some reservation and surrounding rangelands. The Livestock Grazing Program within the Natural Resources Department was established to assist tribal member cattlemen in developing and maintaining the best possible herds for their families and profit.

The climate of the Four Corners Region is classified as semiarid and is characterized by low humidity, cold winters and wide variations in seasonal and diurnal temperatures. The region has been in an extreme drought for the majority of the last 20 years. Temperature varies with elevation. The average monthly maximum temperature ranges from 39°F to 86°F, and the average monthly minimum temperature ranges from 18°F to 57°F. The highest and lowest temperatures occur in July and January, respectively. Precipitation also varies with elevation, with average annual precipitation amounts of 8 to 10 inches in the lower elevations of the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation and about 13 inches at Cortez (Butler et al.,

1995). The 50-year (1948 through 1997) annual precipitation minimum was approximately 5.2 inches at Cortez (1989) and the 50-year maximum was 30.8 inches at Mesa Verde National Park (1957) (EarthInfo, Inc., 2000). Average monthly precipitation varies from 0.65 inch in June to 2.00 inches in August. At the higher elevations, the monthly precipitation totals are relatively constant throughout the year with the exception of the dry season, which occurs in April, May and June. At lower elevations, a relatively drier season occurs from April through June and a relatively wetter season occurs from August through October. Summer precipitation is characterized by brief and heavy thunderstorms. The snowfall season lasts for seven to eight months, with the heaviest snowfall occurring in December.

UTE MOUNTAIN UTE RESERVATION MONTHLY CLIMATE AVERAGES

Source: www.weatherwx.com/climate-averages/co/ute+mountain+indian+reservation.html

A portion of the Farm & Ranch

7,700-acre operation.

In the Four Corners Region, rangeland and forest account for roughly 85% of the entire area, and they cover large areas of the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation as well. Primary land uses on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation include housing for tribal members, tribal offices, natural gas, sand and gravel extraction, grazing for tribal livestock, and business enterprises that provide jobs for its people, including the following:

UTE MOUNTAIN FARM & RANCH

| www.utemtn.com

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s Farm & Ranch Enterprise is a 7,700-acre productive, modern irrigated agricultural project nestled below the Sleeping Ute Mountain on Ute Mountain Ute Tribe land in the southwest corner of Colorado. As a good steward of the land, the Tribe practices sustainable farming and uses state-of-the-art technology to grow and mill corn without GMOs. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s partnership with Bow & Arrow brand corn products began in 1962 and they’ve been proudly producing high-quality products ever since. Bow & Arrow Brand is part of the Ute Mountain Ute Farm & Ranch Enterprise and contributes to the full-time employment of 34 tribal members and other qualified farming experts. The Bow & Arrow brand cornmeal (blue, yellow and white) can be purchased directly from the Tribe at bowandarrowbrand.com and recipes can be found on its website. Bolder Blue Corn Tortilla Chips are made from Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s blue cornmeal and are distributed worldwide. Cattle, alfalfa, wheat and more are also raised. Farm & Ranch has consistently ranked high in both state and national corn yield contests sponsored by the National Corn Growers Association. A modern 500,000 bushel storage facility enables Farm & Ranch to store and market grains as market situations become favorable.

Ute Mountain Farm & Ranch’s source of irrigation water is the McPhee reservoir, Colorado’s second largest man-made reservoir. Irrigation water travels 40-plus miles in open canals and through siphons to reach the Farm. It then is guided through underground laterals to a total of 109 pivot sprinklers. Because of the elevation difference between the canal and the fields, pressure is developed as it travels to the fields, enabling the use of pivot sprinklers. Modern technology enables Farm & Ranch to monitor all irrigation systems by use of computers and cell phones in real time. Given the increasing and projected drought conditions of the region, water is a precious commodity and the efficient use of this resource is of top priority. Farm & Ranch is currently partnering with the Colorado Department of Agriculture and the Natural Resource Conservation Service in constructing a 10-mile site micro-hydro project. Excess water pressure produced in the existing irrigation system is captured and used to turn turbines to produce electricity that is used exclusively at the farm and mill facility. Sites one through five have been constructed. Two sites were commissioned last year and three sites are ready for commissioning now. The final five sites are planned for construction in the next 12-18 months.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm & Ranch Enterprise offers employment opportunities for tribal members and other qualified individuals. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s Farm & Ranch operation significantly contributes to the Tribe’s economy as well as member benefit. For example, Farm & Ranch donates five to eight head of cattle annually for the Bear Dance celebration; contributes over $1.1 million in dividends from cattle; provides an annual garden for tribal members with sweetcorn, vegetables and pumpkins; and provides hay for the Ute Mountain Resource Department and tribal members.

UTE MOUNTAIN CASINO, HOTEL AND RESORT utemountaincasino.com

Ute Mountain Casino Hotel is a property of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. Located in Towaoc, Colorado, it’s the state’s first tribal gaming facility and home of the newest and hottest slots in the Four Corners Region. The casino gaming floor is packed with over 700 slot machines, Vegas-style table games, the best bingo hall in Colorado and a brand-new sportsbook.

Located 20 minutes from the entrance to Mesa Verde National Park and nestled in the shadow of the legendary Sleeping Ute Mountain, the hotel offers Southwestern hospitality, friendly faces, great food and gaming excitement! The hotel at Ute Mountain has 90 comfortable and newly renovated rooms, including full suites, junior suites, spa suites, a swimming pool and a workout facility.

WEEMINUCHE CONSTRUCTION AUTHORITY | wcaconstruction.com

Weeminuche Construction Authority (Weeminuche) was formed in 1985 by the Tribal Council of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe with the charter to provide employment for tribal members and to generate profits for the Tribe. For decades, Weeminuche was the Tribe’s only construction company, performing vertical and horizontal construction on the reservation. Weeminuche also performed work off-reservation, including the $245 million Animas-La Plata dam project. In 2013, the Tribal Council formed WCA Construction, LLC (WCA) as the enterprise for all construction work to be performed off-reservation. Since 2020, WCA has been certified as an 8(a) firm, Indian Small Business Economic Enterprise and HUB Zone firm. WCA has both a civil and vertical division and is licensed in the Four Corners states. The civil division focuses primarily on water and water delivery projects but also performs road and bridge construction, utility installation, site grading and other civil works. Currently the civil division is building the $45 million first phase of the Arkansas Valley Conduit project for U.S. Bureau of Reclamation as well as several projects for the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, Navajo Division of Water Resources, Montezuma Valley Irrigation, BIA Safety of Dams, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Park Service. The building division constructs commercial and industrial buildings as well as housing projects

on neighboring reservations. Clients include fire districts, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, the White Mountain Apache Tribe, the Navajo Housing Authority, the City of Cortez and other various private and municipal owners. In 2024, the Tribal Council formed Ute Mountain Construction, LLC (UMC) as a second enterprise for off-reservation work. The company is still being set up, but will also be certified as an 8(a) firm, Indian Small Business Economic Enterprise and HUB Zone firm in the coming months. Weeminuche continues to operate solely on the Ute Mountain reservation, performing projects for the tribe. Maintenance of over 250 miles of road, housing rehabilitation, utility installation and construction of new homes and commercial buildings make up the core of Weeminuche’s work. In addition to the infrastructure improvement projects, Weeminuche provides equipment and resources for both Bear Dance and Sun Dance annually. In addition, Weeminuche operates two commercial gravel pits on the reservation, one in Towaoc and one near the Four Corners Monument. Aggregates are produced in these pits for Weeminuche’s projects, the Tribe and commercial sales. Collectively, the construction companies generate roughly $20 million in revenue and $1.4 million in profit, 20% of which is distributed to the UMUT. In addition to that, Weeminuche operates at a loss of roughly $1.5 million per year completing projects for the Tribe. Weeminuche gravel pits produce 8,000 tons per year of gravel that is free to tribal members and generates revenue in the form of royalties from gravel production at 7.5% of sales. Overall, the above combines to $1.9 million that the construction enterprises provide to the Tribe annually. Construction employee counts range seasonally from 75 to150 employees. Roughly 50% are UMUT tribal members and 70% overall are Native American. The construction group has a tribal member development program that focuses on providing career development guidance, reviews and detailed development plans. In 2023 alone, 240 training courses were conducted with topics ranging from basic computer skills to project management, leadership and supervision.

PROUD AND RESILIENT PEOPLE

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe are the Weenuche band of the Ute Nation of Indians. The two other bands, the Mouche and the Capote, became the Southern Ute Tribe. The Northern Ute Bands (the Uncompahgre band, the Grand River band, the Yampa band and the Uinta band) are located on the Uinta Ouray Reservation near Vernal, Utah. The Ute Indians are distinguished by the Ute language, which is Shoshonean, a branch of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic stock (Garcia and Tripp, 1977). Other Indians in the United States that speak Shoshonean are the Paiute, Goshute, Shoshone and several California tribes.

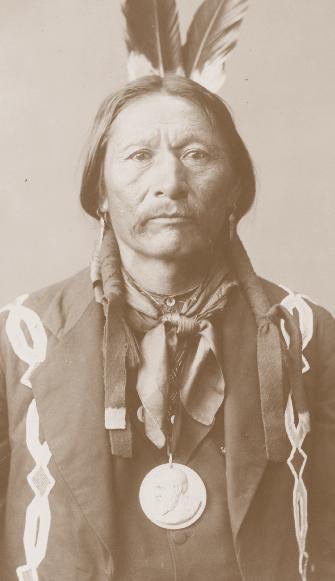

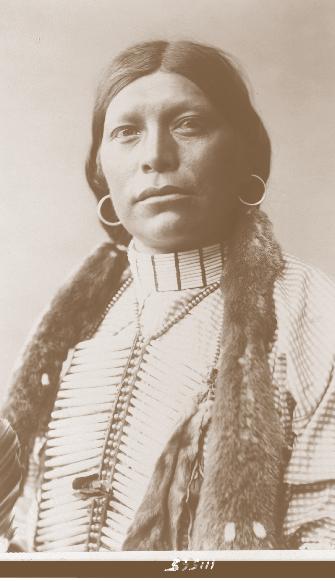

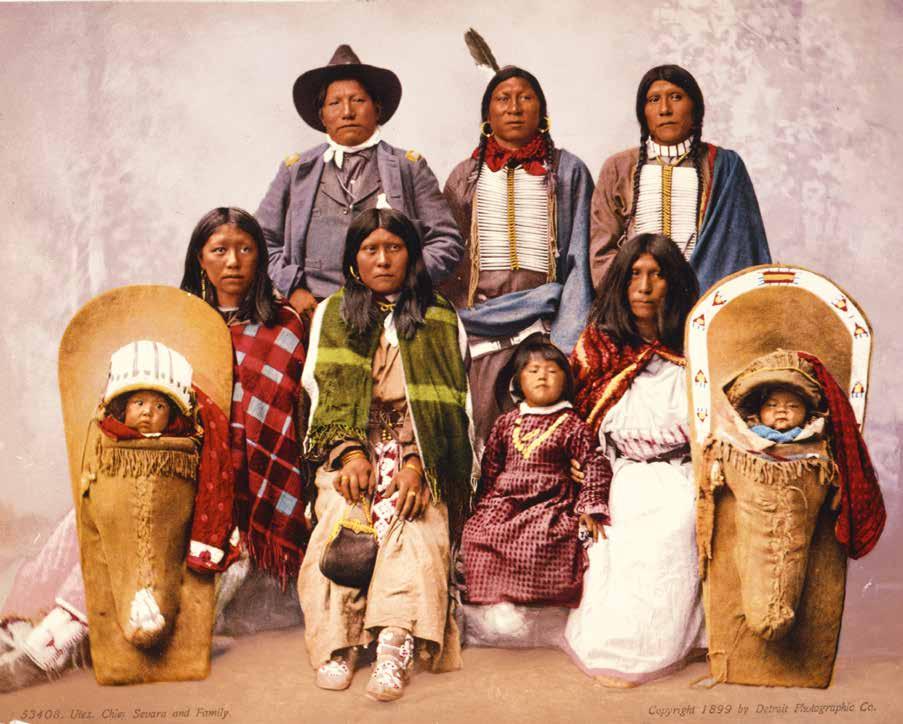

Uinta Ute warrior and his bride on horseback, in northwest Utah, c. 1874.photographed by John K. Hillers. The bride wears a cotton long-sleeved blouse, over which a geometrically patterned length of fabric is worn over one shoulder. Her groom wears a porcupine quill vest, a loincloth and cartridge belt, and holds a rifle. His arms and legs are painted with linear patterns.

If I am in harmony with my family, that’s success.

— Ute proverb

According to the U.S. Census, the population of Towaoc, Colorado, in 2020 was 1,140, with 61% female and 39% male; the median resident age was 22.6, in comparison to 36.9 years for the rest of Colorado. The town of White Mesa, Utah, is home for just 138 residents and is demographically similar to Towaoc, with local residents being characterized by high degrees of poverty and rural isolation (the nearest city with a population of 50,000 or more is nearly 200 miles away). Youth under age 18 constitute more than half the resident population at the UMUT Reservation, virtually double the proportion found in most American communities. The number of children and youth tribal members and non-tribal members is 600. The total UMUT population between the two regions is 1,318 (63% of total UMUT membership).

GROWTH OVER TIME

In 2010, the population in Towaoc, Colorado, was 932, representing a 22% increase over the last ten years. The population of White Mesa decreased from 228 to 138 people. Total UMUT membership remained fairly stable at 2,100.

GROWTH PROJECTIONS

The overall tribal population on the UMUT Reservation is expected to remain consistent for the foreseeable future. The current blood quantum requirement for tribal membership is 50%. Considerations for lowering the blood quantum requirement for membership have not yet been decided.

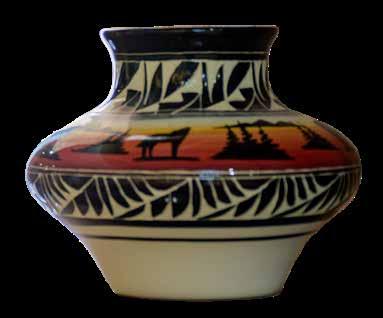

UTE MOUNTAIN UTE TRIBE POTTERY

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Pottery aims to preserve and promote the rich cultural heritage of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe through the creation and sale of traditional and contemporary pottery. Its mission is to provide high-quality, authentic pottery that reflects the artistry and traditions of the Ute Mountain Ute people, while also creating economic opportunities for tribal members.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Pottery and Gift Shop, which reopened in 2025, offers a unique brand of pottery and cultural gifts to tourists in Cortez, Colorado. The Pottery itself gives visitors and residents a place to go to understand and learn about Native American culture. After re-opening following the COVID-19 shutdown, the building has been restored and is again a cultural destination, as it was before.

The Pottery is owned by the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and offers a program for youth and adults to work, as well as learn about entrepreneurship, by helping with grand tours they host to schools and tourists in the area. While the Pottery is open year round, summertime is the busiest season, and everyone is more than welcome to come. There is also a small entertainment table for children to draw and paint as they please. All pottery is made in the shop itself, with windows that allow you to watch the pottery being hand-painted.

Most of the staff is also dressed in traditional clothing — ribbon skirts, handmade moccasins and beaded jewelry — to show others how beautiful the Native American culture is. Soon, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Pottery will be opening a shop at the Four Corners Monument and offering online shopping so many more can purchase these authentic artisan pieces.

with skilled fingers, we paint our history, molded with sharp clay, and designs born of work beaded necklaces, thick-skinned moccasins we share our time and craft with you.

time may pass but our stories remain; you will hear them told again someday people of all colors can speak together; let’s walk and share the old way.

we welcome the youth to take part, art shaped by small fingers – treasures of our world. to create, to listen, to understand –all for the good of our shared earth. beautiful hues of turquoise line our chains, mountains engraved deep in our rings. small drums nestled in our palms, beating with joy and peace as we sing.

from our grandparents, now to you –show the world our paths of colors. feathers to rough-skinned hide, carry forth what we have taught you. though we may not live as we once did, our paths brought us to this joyous day thank you for sharing your hearts with us –we hold you in prayers as we pray.

ARTS, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE

Ute

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe people are determined to preserve and protect their culture and language. Two ceremonies have dominated Ute social and religious life: the Bear Dance and the Sun Dance. The former is indigenous to the Ute and was originally held in the spring to coincide with the emergence of the bear from hibernation. The dancing, which was mostly done by couples, propitiated bears to increase hunting and sexual prowess. The theme of rebirth and fertility is pervasive throughout. The Sun Dance was borrowed from the Plains tribes between 1880 and 1890. This ceremony, for men only, is held in mid-summer, and the dancing lasts for four days and nights. The emphasis of the Sun Dance was on individual or community esteem and welfare, and its adoption was symptomatic of the feelings of despair held by the Indians at that time. Participants often hoped for a vision or cures for the sick. Consistent with the emphasis of this ceremony was the fact that dancing was by individuals rather than couples, as was the case with the Bear Dance. Both ceremonies continue to be held by the Ute, although the timing of the Bear Dance tends to be later in the year. The Ute enjoy singing and many songs are specific to the Bear Dance and curing. The style of singing is reminiscent of Plains groups. Singing and dancing for entertainment continue to be important.

Our traditional ceremonies Beardance and Sundance Was our communication to meet and Introduce our families to one another. We could never meet due to our traveling, But I’m happy to see you and know your name.

I hope after this harsh winter coming I can see you again.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

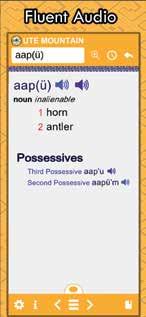

Over the past nine years, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has produced award-winning books, films, language apps and websites. In all, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has won more than 50 Telly, Anthem and Webby Awards for these productions.

LANGUAGE PRESERVATION PRODUCTS

Ute Online E-Learning nuuwayga.com/

Ute Online Dictionary dictionary.utelanguage.org

Ute Language Google App

play.google.com/store/apps/ details?id=org.utelanguage. dictionary

Ute Language Apple App apps.apple.com/us/app/ute-mobiledictionary/id1594696386

AND

Growing Ute I

issuu.com/a2moons/docs/ growingute_issuu_1028

Growing Ute II

issuu.com/bevsanticola/ docs/growingute2

Land Changes

issuu.com/bevsanticola/ docs/wi_ssiv_ka_av_tu_ vu_pu_a_08sept

Grocery Store Capital Campaign

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/ cc_14june

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/ ceds_2022_0601_digital

Retreat Report

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/umut_ nuchu_report_prf10

FILMS

“Our Culture is Our Strength” (film) vimeo.com/516856356

“We Are Nuchu” (film) vimeo.com/617401273/6cb4761591

“Escape” (film)

www.centerforruraloutreach.org/projects-gallery/ escape-film

“The Strength of Siblings” (film)

www.centerforruraloutreach.org/projects-gallery/ the-strength-of-siblings-film

Suicide PSAs | vimeo.com/661599488 vimeo.com/661599524

Language PSA | vimeo.com/624082360/c1bf5dddb3

Culture PSA | vimeo.com/521216390

“Ute women have been beading for generations. Before contact with Europeans, we made beads from seeds, shells and elk teeth. Colorful glass beads traveled from Europe over new trade routes in the 1700s. The new beads inspired an artistic transformation. We worked with beads in geometric and floral patterns and applied these to shirts, dresses and moccasins.”

“Beadwork should be touched. Beadwork should be worn.

Beadwork should be alive.”

— Mariah Cuch, UMUT, 2013

GRANT SUCCESSES

The UMUT annual operating budget, approved September 30, 2025, for FY 2026 is $90,525,605, with 76% coming from grants and the balance of 24% from other revenue sources. Revenue from business enterprises has been lower in recent years following COVID-19 and the severe drought. The Farm & Ranch enterprise was operating at 20% capacity for an extended period. Increasing costs for materials and labor has adversely affected Weeminuche Construction Authority and the Tribe lost significant revenues from gas and oil. Tribal revenues from its business enterprises are expected to increase in 2026-2027.

Each revenue source contributes to the Tribe’s ability to function as tribal government. Any increase in revenues results in an increase in services and improves the quality of life for tribal members. On the other hand, any decrease in revenues severely limits the Tribe’s ability to provide tribal members with adequate services and social programs, basic living assistance and improved living conditions. Grants and contracts represent the majority of the Tribe’s revenue. The Tribe is listed by the Internal Revenue Services in Revenue Procedure 2002-64 as an organization that may be treated as a governmental entity in accordance with Section 7871. As such, the Tribe’s income is not subject to federal income tax.

Since 2015, following the first Ute Mountain Ute Native National Partnership Retreat, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has generated nearly $176 million in new grant funding. The Tribe contracts with Santicola & Company to assist in the development of award-winning proposals.

TOTAL GRANTS WON FROM 2015 TO 2025

WEAKNESSES AND THREATS

POVERTY

One quarter of UMUT residents live below the poverty level and unemployment is more than double the state’s unemployment rate. Nearly one in three children on the UMUT reservation live in poverty. The estimated median household income in Towaoc is $46,466 in comparison to $87,598 in Colorado. The per capita income of $33,498 in White Mesa is about 90 percent of the rest of the state ($37,023) and unemployment is more than double the state rate.

PER CAPITA INCOME

LIVING BELOW THE POVERTY LINE

2022 data from https://censusreporter.org/profiles/16000US0878280-towaoc-co

HOUSING SHORTAGES/HOMELESSNESS

The housing shortage on UMUT lands is devastating. Families want to live on the reservation to take advantage of tribal benefits, such as proximity to family support systems, and tribal services, such as health care, social services and cultural programs. As of April 14, 2023, there were no properties to buy or rent at any price on the UMUT Reservation. Housing in the communities surrounding UMUT lands are beyond financial means of tribal members. To solve this challenge, families “double up,” sometimes reaching four separate families living in the same structure. The current list of families awaiting affordable housing opportunities includes applications from 2008, 2009, 2011 and 2013 – families that have been living in unsafe, overcrowded conditions for over a decade. The aging housing stock of the UMUT Reservation further complicates this issue, leaving families in homes with leaking roofs, faulty wiring, broken gutters and plumbing challenges that lead to mold. In 2019, the Colorado Health Foundation, Colorado Housing and Finance

HOUSING IMPROVEMENTS 2019 TO 2025

Authority and Colorado Department of Local Affairs donated $300,000 each for a total of $900,000 in hopes the Tribe could make emergency health and safety repairs to 12 homes at approximately $75,000 per home. The Bureau of Indian Affairs Tiwahe Initiative also granted $734,604 over three years for housing improvements. Through this program, called Colorado Ute Mountain Helping Hands Home Improvement Program, 28 homes have been renovated since 2019 for a total of $2.8 million. The average cost per home was $80,000 and some exceeded $190,000. The housing rehabilitation program will continue in 2026 with additional funding awarded from Colorado Health Foundation ($300,000); Colorado Housing and Finance Authority ($300,000), State of Colorado ($600,000), Tiwahe ($281,000), and First National Bank of Topeka ($500,000). We also applied for $2,250,000 from First National Bank of DesMoines for White Mesa housing rehabilitation.

FOOD INSECURITY

The USDA defines “food desert” as a tract in which at least 100 households are located more than one-half mile from the nearest supermarket and have no vehicle access, or where at least 500 people or 33% of the population live more than 20 miles from the nearest supermarket, regardless of vehicle availability. Both UMUT Reservation communities of Towaoc and White Mesa qualify as food deserts, which the USDA defines as parts of the country with low levels of access to fresh fruit, vegetables and other healthful whole foods, usually in impoverished areas. Tribal residents in Towaoc must travel 20 miles or more to reach the nearest full-service grocery store. This distance is difficult for all tribal members, but particularly devastating for the 32% of residents who utilize SNAP benefits to purchase groceries. The only option for food in Towaoc is the Travel Center, which sells food typical of an interstate truck stop, or the Casino Hotel.

TOWAOC

DIABETES

One in four tribal members have

Type II diabetes

People with diabetes have 2.3 times higher annual medical costs than people without diabetes, with an average of $9,601 in diabetes-related expenses per year.

With 500 tribal members with Type II (diet-related) diabetes:

$9,601 per person, per year x 500 tribal members with diabetes = $4.8M per year x 50 years (avg. lifetime with diabetes)

= $240M total in diabetes-related medical care over 50 years

The Center for Disease Control reports Native Americans have a greater chance of having diabetes than any other U.S. racial group.1 The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe serves a Native American population battling obesity, prediabetic conditions and Type II diabetes at rates far greater than any other subpopulation in the nation. Across the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, obesity impacts entire families and burdens children with unhealthy lifestyle habits before they reach their 10th birthday. Young adults are diagnosed with preventable Type II diabetes before they reach middle age, and elders struggle to self-monitor and maintain healthy A1C levels. Without access to fresh foods and healthy ingredients needed to prevent and address diabetes among the older generations, younger generations do not build the knowledge, skills and habits they need to prevent diabetes, creating an intergenerational successive pattern that continues to intensify.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe reports a life expectancy of 55 years – 20 years fewer than the average American. The 2016 UMUT Community Health Assessment states one in four tribal members have Type II diabetes. Over 70% of adults and 50% of youth are struggling with obesity.

The best practice to prevent and manage Type II diabetes is to maintain a healthy diet. Research shows that grocery stores with abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats and low-fat dairy products result in healthier choices for consumers. Diabetes Journal reports that a person diagnosed with diabetes at age 40 will have $211,400 in additional lifetime medical expenses. The estimated lifetime cost of treating and living with diabetes for an individual who has had diabetes for 50 years is $395,000. In 50 years, 500 tribal members with diabetes will spend a collective $197.5 million on treatment alone. This robs the Tribe of collective resources which could be better spent on healthy food, education and higher quality of life.

The root causes of health disparities related to diabetes among the Ute Mountain Ute are complex and intrinsically linked to the history of Native Americans in modern America. Solutions must be equally comprehensive and culturally specific. Devastating health challenges related to widespread obesity, prediabetic conditions and diabetes can be overcome.

1 https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aian-diabetes/index.html

In shadows cast by sugar’s sway, Diabetes looms, an unwelcome fray. Yet through the darkness, light can gleam, With strength and courage, it’s not a dream.

With each sunrise, a chance to fight, To keep blood sugar levels right. Healthy meals and exercise, they say, Are the allies to keep it at bay.

Monitor, manage, never despair, For in resilience, we find our share Of hope and healing, day by day, Together, we’ll navigate this way.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

HEALTH DISPARITIES

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

In fall 2021, 63% of parents of Native American students indicated they do not believe “all students’ cultures are acknowledged and respected in school.”

On a national scale, Native Americans lag in attainment of higher education. For example, only 16% attain a degree, compared with 33% country-wide. Similarly, only 5% of UMUT tribal members have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 35% in the state of Utah and 42% in Colorado. Further, only 76% of tribal members have a high school diploma compared to 93% in the state of Utah and 92% in Colorado. Though a substantial number report having attended some college, the graduation rates remain stagnant (SWCAHEC).

At this time, the vast majority of UMUT children are bussed to Montezuma Cortez schools, a journey that can take nearly an hour in each direction. Against all standard measures, Ute students demonstrate a desperate need for culturally aligned educational options. For generations, traditional public school assessments have shown Ute youth are far behind non-tribal peers in academic performance. The Montezuma Cortez School District RE-1 Report on the Progress of American Indian Students from October 2021 shows the following statistics:

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF UMUT CHILDREN ■ VERSUS NON-TRIBAL AFFILIATED STUDENTS ■

Although Montezuma Cortez School District RE-1 offers K-12 education, approximately 33% of UMUT high school students attend various boarding schools around the country, such as Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma, due to suspensions and a need for alternative options.

Students at public schools say they are bullied and treated as second-class citizens. The public school system is primarily interested in using the tribal students or tribe as a number to substantiate a need for more grant funding and programs rather than providing real help. Native American students who are failing will often drop out or, in some cases, are actually pushed out, whereby they have little alternative except to pursue GED certificates rather than pursue high school diplomas and must contend with the dropout stigma in pursuit of higher education. Caught in the stigma of low self-esteem, many Indian students continue their downward spiral, applying for entry-level jobs at either the tribal casinos or one of the other enterprises/departments within the Tribe. Individuals and families suffer from the effects of educational under-attainment, extensive drug and alcohol abuse, domestic violence and crime. UMUT Tribal Human Resources reports show that tribal workers are too heavily under-educated. Of the 657 tribal members and other Native Americans currently working full-time for the Tribe, approximately 250 have not completed a secondary diploma. Based on temporary worker intake forms, the number of adults lacking a secondarylevel diploma in Towaoc is as high as 600. Poor overall academic proficiency levels and extraordinarily low high school graduation rates among UMUT youth are further indicators of this critical lack of college and career-readiness.

As noted, both UMUT tribal communities are highly rural with no nearby population centers that offer college degree or industry certification opportunities. While 2017 survey results show that community members are nearly unanimous (91%) in agreement that some form

There can be little doubt that the current educational system is failing Ute children

80–90%

of high school graduates don’t have the financial means or transportation to attend college

of post-secondary education is essential for personal and/or tribal economic uplift, the lack of public transit and too few personal vehicles (estimated at one operable vehicle for every four work-age adults) make commuting to a college or training center unusually difficult, costly and stressful. Further, 80–90% of high school graduates don’t have the financial means or transportation to attend college. And while the Tribal Council provides fully funded scholarships, many students are emotionally or academically unprepared for it. The distance from the tribal reservation to qualified post-secondary institutions, workforce centers or educational nonprofits are in the range of 25 to 65 miles — with no intermediary services between. The nearest accredited internship program is more than 70 miles away in New Mexico. Even when these facilities are reached, the resources often prove extremely limited in scale or reliability, due to fiscal starvation.

According to a 2015 education-related survey of UMUT tribal residents, 43% say that lacking funds for childcare has prevented their efforts to further their education. The most frequently cited reason from students who drop classes or trainings in Towaoc, according to follow-up calls, is “having to work so we could eat.” Among adults using Ute Mountain Learning Center resources, 92% of “currently employed” participants reported they were seeking classes to improve their earnings potential and/or job standing (promotability). Fewer than 18% of respondents indicated that they were prepared for collegiate reading (and concomitant critical thinking) and less than 5% were ready for collegiate math.

HEALTH INEQUITIES

Approximately 41% of tribal members do not have health insurance. Teen birth rates are among the highest in the nation, and the likelihood of low birth weight is significantly higher than averages for other regions. Teen suicide has reached epidemic levels among the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. In August 2016, just one week into the new school year, the Tribe lost a high school junior — a popular young man with a bright and promising future. In November 2016, the community lost another child to suicide, a young lady just beginning her high school career. In early 2020 there were two completed suicides and five attempts by teen girls and boys. Historically, UMUT sees an average of 2-5 youth suicides per year, but this doesn’t tell the whole story. Reported rates do not consider UMUT youth living offreservation, attempted suicides, drug overdoses or those not ruled an “obvious” suicide.

SOCIAL & HEALTH OUTCOME INDICATORS

Towaoc is a Medically Underserved Population (GOV MUP) and is also a designated Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). Similarly, White Mesa is also a designated HPSA and MUP (score of 41, ID #03535). According to the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps website (www.countyhealthrankings.org), in terms of overall health outcomes and social and economic factors, both Montezuma County and San Juan County rank poorly in comparison to other counties in their respective states. Key indicators are shown in the table below.

Montezuma County, Colorado, and San Juan County, Utah, report risk factors that are higher than state and national averages across a wide range of indicators. Ute tribal members live

in communities where residents are far more likely to be in poor health and to be without health insurance. For those who are insured, coverage doesn’t guarantee access to needed services. Living a long distance from providers, not being able to find providers who accept some insurers’ relatively low reimbursement levels or navigating the system to attain a referral prove challenging to receiving treatment. The alarming concerns surrounding Native American child and adolescent health came into the spotlight upon President Obama’s visit to South Dakota’s Sioux tribe in 2014. The Department of Justice followed up with a report on his findings noting Native children’s unhealthy exposure to violence. This, combined with a toxic collection of pathologies — poverty, unemployment, domestic violence, sexual assault, alcoholism and drug addiction — has seeped into the lives of young people living on the UMUT Reservation. The report was followed by the White House’s 2014 Native Youth Report on the state of education in Indian Country. Combined, the reports reveal trends of overwhelming poverty, epidemic suicide, combat-level rates of PTSD and low educational attainment amongst UMUT youth. To exemplify the severity of the issue, suicide is the second leading cause of death for Native youth aged 15-24 and occurs 2.5 times the national rate; 1 in 5 Native youth report having considered suicide.

Suicide among Native youth is 2.5 times the national rate

BROADBAND ACCESS

While the UMUT is currently working on a $40 million broadband initiative that will be completed in 2026-2027, current access to high speed broadband on the UMUT Reservation is limited, at best. Accessibility issues are similar in both Towaoc and White Mesa. According to data obtained from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2017, 54.71% of the UMUT Reservation does not have access to any providers of broadband internet.

FCC figures show that only 45.29% of the UMUT Reservation has access to one or more broadband providers. No area of the reservation has access to multiple providers. According to the FCC, the term broadband refers to high-speed internet access that is always on and is faster than the traditional dial-up access. Broadband includes several high-speed transmission technologies such as:

■ Digital Subscriber Line (DSL)

■ Cable Modem

■ Fiber

■ Wireless

■ Satellite

■ Broadband over Powerlines (BPL)

It is important to note that in 2015, the FCC, tasked with overseeing the rules that govern the internet, raised the standard for broadband to 25 megabits per second from 4 Mbps, while raising the upload speed to 3 Mbps from 1 Mbps. Using these new standards, no area of the UMUT Reservation has access to high-speed broadband internet. The lack of highspeed internet further exacerbates poverty, health and educational inequities because it limits access to distance learning and telemedicine services.

During COVID-19, UMUT students had to sit in cars in a parking lot to get homework assignments. A Comprehensive Broadband Plan was developed in 2020-2021 and is included in the Disaster Resiliency and Recovery section of this plan.

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation is limited on the reservation, with the main mode of transportation being the personal car and the tribal transit system. The transit system consists of one van run on a fixed five-day schedule and the casino shuttle that delivers riders for employment purposes.

There is no easy way to get to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Reservation, and no easy way for tribal leaders to get to Denver or Washington, DC, to meet with state and federal legislators and funding partners. In addition, there is no easy way for the Tribe’s 2,100 members to access many vital resources, specialty medical care or educational opportunities. Even travel to the tribes Farm & Ranch Enterprise for employees and residents is more than 20 miles one way on a dirt road.

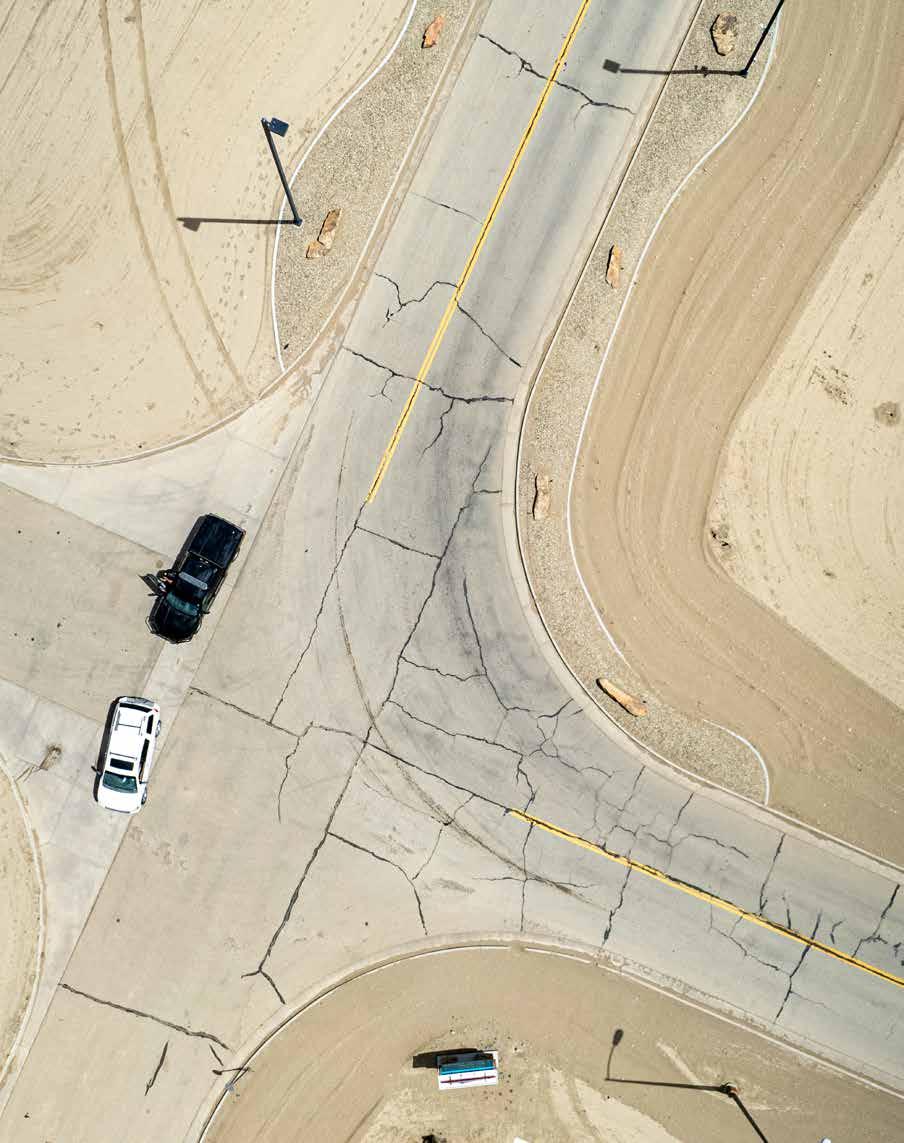

Towaoc is located in the southwest corner of Colorado, near the Four Corners Monument connecting the four states of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona. The transportation network serving the region is limited due to topographical constraints, sparse population and the distance between urban areas. No interstate highway systems traverse the area; however, several interstate highways connect urban areas that have secondary feeder roads that serve the rural areas. These include Highway 491 north to Cortez and south to Shiprock and Gallup, New Mexico; Highway 160 to Teec Nos Pos, Flagstaff and Phoenix, Arizona; and Colorado Highway 41 to White Mesa and Blanding, Utah. Currently, no major railroad lines serve the region, the nearest being Gallup, New Mexico, 124 miles to the south. Small commercial airports are located in Cortez, Durango and Farmington, with even smaller limited-service airports located in other communities.

WATER AND WASTEWATER

The reservation is serviced by several logistically placed sewer lagoons, and all wastewater is disposed into these lagoons. Recent expansion of the lagoons has increased service and long-term capabilities of the wastewater program. There were five major main supply breaks in 2016 alone along the 27 miles of pipeline connecting Towaoc to the water treatment facility in Cortez. Because the three water towers/tanks in Towaoc can only store approximately 24 hours’ worth of water, this is a critical health issue on the reservation and served as a spark for an array of large and small-scale water infrastructure improvements.

The area’s water supply from the Dolores River — a tributary of the Colorado River — is affected by overall water shortages resulting from overallocation of water rights and climate change driven drought conditions. The Tribe has principal water rights to water within Lake Nighthorse, located outside of Durango, Colorado, but no infrastructure to bring the water 50 miles west to the reservation.

The people living on the reservation in White Mesa, Utah, have it even worse. On a high-desert bench overlooking Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah, what began as a mill built to break down rock and process natural uranium ore has become a commercial dumping ground for low-level radioactive wastes from contaminated sites across America and the world.

Haul trucks headed for the mill have splattered radioactive sludge along the route the children of the nearby Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s White Mesa Reservation community travel

to school. Plumes of contaminants, including nitrate and chloroform, have been detected in the groundwater beneath the mill. The mill also emits radioactive and toxic air pollutants that can travel off-site, including radon, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide.

For decades, the mill’s unconventional business model — pocketing millions of dollars in exchange for processing and disposing of hundreds of millions of pounds of radioactive waste — has flown largely under the public’s radar. Piecing together the public records of these wastes connects the White Mesa Mill to some of the most infamously contaminated places in the country.

At the recent Nuchu: Planning Our Vision Native National Partnership Retreat, one resident of White Mesa told over 50 funding partners the story of how the water in White Mesa has caused him and his wife serious health problems.

“My health and life expectancy has significantly been adversely impacted by the water in White Mesa and I worry that I won’t live long enough to see my children graduate from high school or dance at their weddings. My wife and I both have lumps on our bodies we never had before. I’ve had two back surgeries recently and need to use a scooter to get around.”

You must dream of our dance first to participate And we will know it was meant for you.

Our hair holds memories of our life, All the people we meet and everything we’ve ever done.

I pray for your health and happiness

And when the day comes I am gone, Cut your hair to take away the bad energy. Our memories will hold a place in your heart.

— Kamea (Mia) Clark

DISASTER RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE

UTE MOUNTAIN UTE TRIBE DISASTER RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE PLAN

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is committed to ensuring the safety and wellbeing of its members and the preservation of its cultural heritage in the face of potential disasters. This plan outlines the strategies and actions necessary to prepare for, respond to and recover from disasters, while enhancing the Tribe’s overall resiliency.

OBJECTIVES

1. Protect Lives and Property: Ensure the safety of all Tribe members and minimize damage to property.

2. Maintain Essential Services: Ensure the continuity of essential services and functions during and after a disaster.

3. Preserve Cultural Heritage: Protect and preserve the Tribe’s cultural heritage and resources.

4. Enhance Resiliency: Strengthen the Tribe’s ability to withstand and recover from disasters.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Conduct a comprehensive risk assessment to identify potential hazards, including natural disasters (e.g., wildfires, floods, earthquakes) and human-made threats (e.g., hazardous material spills, cyberattacks). Assess the vulnerability of Tribe members, infrastructure and cultural resources to these hazards.

PREPAREDNESS

1. Emergency Planning: Develop and maintain emergency response plans for various types of disasters. Ensure that these plans are regularly updated and practiced through drills and exercises.

2. Training and Education: Provide training and education to Tribe members on disaster preparedness, response and recovery. Conduct workshops and distribute educational materials.

3. Resource Management: Identify and maintain an inventory of resources and supplies needed for disaster response and recovery. Establish agreements with neighboring communities and organizations for mutual aid and resource sharing.

RESPONSE

1. Emergency Operations Center (EOC): Establish an EOC to coordinate disaster response efforts. Ensure that the EOC is equipped with necessary communication and information management tools.

2. Communication: Develop a communication plan to ensure timely and accurate dissemination of information to Tribe members, emergency responders and external partners.

3. Evacuation and Sheltering: Identify evacuation routes and establish shelters for Tribe members. Ensure that shelters are equipped with necessary supplies and can accommodate individuals with special needs.

RECOVERY

1. Damage Assessment: Conduct a thorough assessment of damage to Tribe property, infrastructure and cultural resources. Document the extent of damage and prioritize recovery efforts.

2. Restoration and Reconstruction: Develop a plan for the restoration and reconstruction of damaged property and infrastructure. Ensure that cultural resources are preserved and restored.

3. Financial Assistance: Identify sources of financial assistance for disaster recovery, including federal and state grants, insurance and private donations. Provide assistance to Tribe members in accessing these resources.

RESILIENCY

1. Infrastructure Improvement: Invest in infrastructure improvements to reduce vulnerability to future disasters. This may include upgrading buildings, roads and utilities to withstand extreme conditions.

2. Community Engagement: Foster a culture of resiliency within the Tribe by engaging members in disaster preparedness and recovery efforts. Encourage community participation in planning and decision-making processes.

3. Partnerships: Establish and maintain partnerships with local, state and federal agencies, as well as non-profit organizations and private sector partners, to enhance the Tribe’s disaster resiliency.

CONCLUSION

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Disaster Recovery and Resiliency Plan is a living document that will be regularly reviewed and updated to reflect new information, changing conditions and lessons learned from past disasters. By working together, the Tribe can ensure the safety, well-being and resilience of its members and cultural heritage.

OVERVIEW OF GOALS AND STRATEGIES

As part of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe CEDS, this resilience/diversification strategy is designed to serve as a roadmap to empower the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe to establish goals and objectives, develop and implement a plan of action and utilize resources efficiently to build resilience and economic diversity in the region. There is no silver bullet in this arena. Resilience and diversification are a series of long-haul strategies to secure success through multiple community initiatives coming together to provide support and balance to one another.

Moving forward, continued community engagement at the local, regional, state and national levels will be critical. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is unique to Colorado, the Four Corners Region and the country. The area is steeped in history and generations of traditional families that have created a modest living in a sometimes-brutal natural environment and with few “urban” resources.