4 minute read

Fundamental Figures

More than 80 years after Bentley’s doors opened to coeducation, four of ‘the firsts’ tell their tales

Advertisement

BY KRISTIN LIVINGSTON

ART BY DANA SMITH

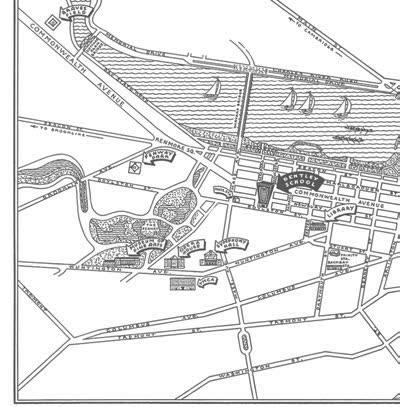

Much of history is a book filled with the stories of men, written by men —- and the Bentley of 1917 was no exception to the times: a school founded by a man for male accountants. Thankfully for the university as it stands today, in 1941 women were not only finally, officially admitted to Bentley, but accepted, supported and celebrated.

It’s time to fully witness this journey of more than eight decades. Let’s start by peeling back the sepia filter on four of their number: Bentley women who never intended to pioneer a thing but, just by being themselves, helped write history for all who followed.

A String of Pearls

1945, Exeter, New Hampshire

For almost 100 years, the Robinson Female Seminary was housed in the old Exeter town hall. Each school day, flocks of girls raced up and down the grand Victorian mansion to class, studying history and English, geology and domestic science. Mary (Durgin) Kline ’48 was one of Robinson’s star math pupils. For her, numbers were as easy to piece together as the colors in a quilt. All it took was a quick step back to see the pattern.

Eight miles up the road and a generation back, the names Durgin and Gallant had meant something. The silk mill, the grocery store, the bank — Mary’s family practically owned the town of Newmarket. But, with two world wars and the hospitalization of her father, Mary was waiting tables and doing odd jobs from 13 on.

It was her bookkeeping teacher who approached Mary about an accounting school in Boston. “You have a flair for it,” she said.

Mrs. Durgin didn’t approve. Her daughter at an all-boys school, in the city? All by herself? But Mrs. Durgin also realized that, someday, Mary would marry. What if something happened to Mary’s husband, as it had to hers?

1945, Chelsea, Massachusetts

Saturday mornings meant citrus and stacking for Rosaline ’48 and Eunice ’51 Berkowitz. Mountains of oranges. Pyramids of grapefruit. Weekends were a busy time at the family’s kosher grocery store. Fresh produce was their best marketing — and math lesson. Mrs. Berkowitz was a whiz at weighing and calculating each order in her head, and she expected the same of her daughters.

The girls did not disappoint, and never would.

Their father had passed away when Ros was 12 and Eunice 9, bonding them even closer to their mother, a Ukrainian immigrant. “How did I get two crazy children like this?” she’d ask in Yiddish. In their tight-knit Jewish corner of the city, friends looked out for Mrs. Berkowitz. A neighbor offered bookkeeping work to Ros: five days a week for $10. After two months, she was already making $12.

Ros loved numbers because the answer was either right or wrong; there was no in-between. When you finish the job, she reasoned, you know you’re right because everything balances out.

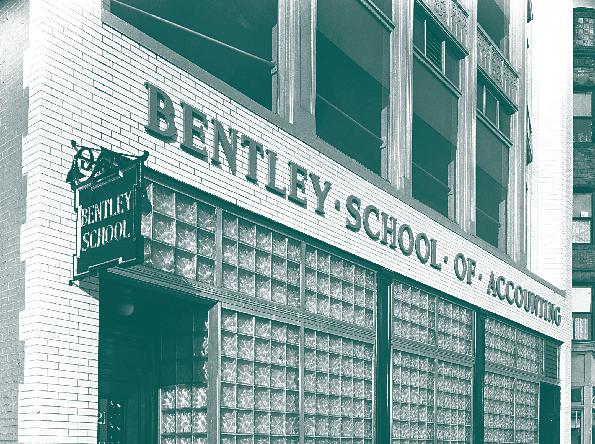

One day she rushed home to tell Eunice: “Bentley’s is admitting women.” That was Mr. Harry C. Bentley’s School of Accounting and Finance, and Ros was desperate to go. But when her letter came, the envelope was as thin as a deli slice. Mrs. Berkowitz grabbed their coats and drove them to Boylston Street.

“We’re all booked up,” Maurice Lindsay, then professor and future president of the school, told them. The war had ended, he explained, and the boys were coming home. Ros tried not to cry — the end of the war was a miracle — but she couldn’t help it. She wanted and deserved a seat.

Professor Lindsay leaned forward. “Go home. You’ll hear from me in a week or so.”

1940, Lawrence, Massachusetts

Elizabeth McAuliffe ’45 always worried about leaving her mother alone.

Mrs. McAuliffe’s first “shock” came when Elizabeth was 14 — a stroke that left her in no position to work. Elizabeth thrived in math and history at school, but the latter didn’t earn much on Main Street. A local auto repair shop hired her as an accountant and teller. She also found work with the area’s first “superstore” that sold all kinds of food and goods. In the limited free time she could muster, she made it out to Canobie Lake Park on a Saturday night to see acts like Tommy Dorsey, but her days as the breadwinner were long.

Three years later, Elizabeth sent her own application to Bentley’s — and soon found herself sitting in a class taught by the man himself.

Take the ‘B’ Train

Each school day, Elizabeth packed her lunch, kissed her mother goodbye, and caught a ride with Dorothy Keighley ’45 to the Haverhill station. The pair studied or played cards with fellow riders to pass the 45-minute ride to Boylston Street, not a Prudential Center in sight. The classroom they stepped into was more gender balanced than one might imagine. Of the 42 day students, 16 were women.

Harry Bentley was steering his school through another world war.

Twenty-six years earlier, World War I had taken 4 million American men into battle — about 4% of the U.S. population at the time. Turning to coeducation for revenue, Bentley admitted 162 women in the fall of 1918. But when an armistice was declared just three months later, many of these new students rightly suspected that returning servicemen would take or resume all the available accounting jobs. Only three women would graduate. And Bentley’s doors closed to women until it faced the same economic dilemma in 1941.

Even so, Elizabeth never felt a social divide or discrimination for her gender. “We sat side by side with the men, and, no matter who you were, no one was allowed an adding machine,” she remembers. Harry Bentley taught taxation himself and employed Elizabeth and Dorothy for two summers: first, as bookkeepers, and then as test students for his course curriculum and proofreaders of his book.

“He trusted us implicitly,” she says. “Working for him over the summer was wonderful because it was just like being back in school, and he was such a nice man.”