Belmont Hill’s History and Social Sciences Magazine

An important note: All opinions and ideas expressed in The Podium are the personal opinions and convictions of featured student writers and are not necessarily the opinions of The Podium staff, the Belmont Hill History Department, or the Belmont Hill School itself.

Suhas Kaniyar, Mikey Furey, Brandon Li, Ernest Lai, Max Glick, Jaiden Lee, Wesley Zhu, Davis Woolbert, Mr. Harvey

Dear Reader,

Marking the end of the current school year, Volume IX, Edition I is the final edition of The Podium for seniors on our staff and a new chapter for the many new members that have joined this spring, each bringing their own talents and skills to one of Belmont Hill’s fastest-growing clubs. One of our most comprehensive issues to date, Edition I contains many intriguing articles highlighting some of the most important events of today and years gone by.

We begin with “History on the Hill,” where Davis Woolbert ‘25 explores the history of the school’s nordic ski team. As always, our op-ed competition yielded a remarkable student turnout. This edition’s winners wrote about denuclearization, potential federal age limits, Houthi rebel attacks, Native American mascots as well as the rise of gambling in the United States.

Volume IX, Edition II features two research papers. First, Noah Farb ‘24 shares the remarkable story of the rise and fall of Jewish-American gangsters in the early twentieth century in his Monaco prize-winning essay. And Suhas Kaniyar ‘28 explores important Supreme Court cases related to the First Amendment.

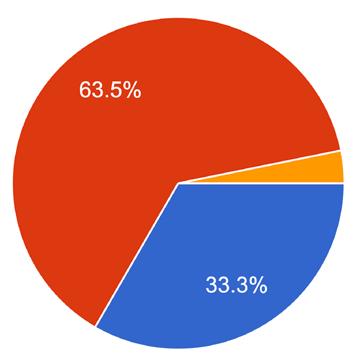

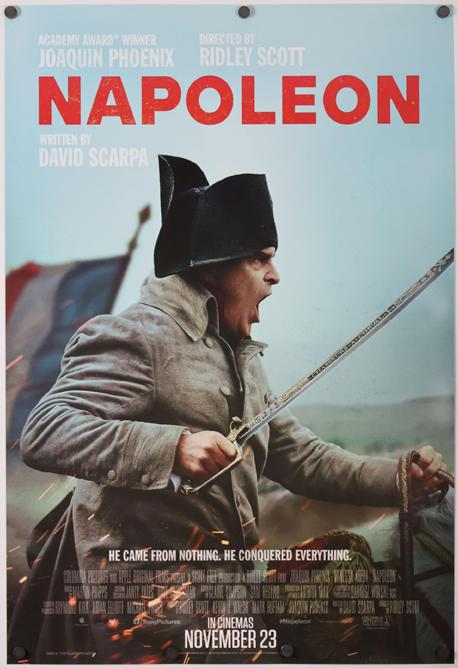

In their data analysis, Ernest Lai ‘25 and Wesley Zhu ‘25 explored Belmont Hill students’ views on the escalating China-Taiwan crisis. In the film review, Mikey Furey ‘25 takes a close look at the recent Napoleon movie which has received a lot of criticism for its alleged lack of historical accuracy. Next, Jaiden Lee ‘26 guides us through the current political landscape of South Korea and Brandon Li ‘26 attempts to answer if global government could be the solution to the world’s problems. Finally, Suhas Kaniyar ‘28 takes a look at Sweden’s admission to NATO and Lucien Davis ‘26 runs through important elections taking place this year.

Volume IX, Edition I is another exciting edition of The Podium. It is chock full of historical insight, political analysis from voices around Belmont Hill and we are thrilled to share it with you. Thank you for picking up a copy and enjoy!

Max Glick ‘24 | President

Ernest Lai ‘25, Wesley Zhu ‘25 | Editors-in-Chief

Mikey Furey ‘25, Christopher McEvoy ‘25 | Executive Editors

Lucien Davis ‘26, Suhas Kaniyar ‘28, Jaiden Lee ‘26, Brandon Li ‘26, Davis Woolbert ‘25 | Staff Writers

Mr. Harvey | Faculty Advisor

Davis Woolbert ‘25

The Nordic Skiing program at Belmont Hill first began in the Winter of 1978. The sport, also referred to as Cross Country Skiing, grew out of the school’s Alpine Skiing program. The sport has seen five head coaches since its inception at Belmont Hill. Coach Bates led the team from 1978 to 1982. Coach Kirby took the helm in 1982 and remained head coach until 2016 before passing leadership of the team to Coach Courtney, who led from 2016 until 2021. Coach Ahearne led the team during the 2021-2022 season before passing the lead to Coach DeCaprio who is the current head coach of the program. The Nordic Skiing team at Belmont Hill has won the Lakes Region Championships numerous times as well as X New England Championships. The team also won the ISSA league 11 times in the 1980’s and 1990’s. The team has experienced numerous highs and lows due to varying snow quantities throughout the years, but success has always remained a hallmark of the program.

The sport of Nordic skiing is a unique one that requires immense endurance and strength in tangent with one another. The sport consists of two primary techniques, classic and skate skiing. Classic skiing utilizes tracks in the snow prepared by a grooming machine. The technique primarily consists of “double poling” on flats and downhills; however, it requires “striding” on uphills (a form of running on skis). Skate skiing is quite different from classic skiing; it requires more space and allows skiers to move their skis laterally to generate more momentum. Due to the obvious reality that, in most areas, nordic skiing can only be practiced on snow during a fraction of the year, a means of summer training called roller skiing was invented. Roller skiing is essentially the same as skiing on snow, except it requires different skis and pole attachments. As a result of these techniques being so dif-

ferent and challenging to master, successful skiers must be well rounded in their technique abilities. Nordic skiing races usually consist of either classic or skate skiing, depending on the race. One of the unfortunate downsides

to nordic skiing is the funding necessary for equipment. Nordic skiing, whether in winter or summer, demands specialized equipment tailored to the distinct techniques of classic, skate, and roller skiing, necessitating separate skis for each discipline and often different boots for optimal performance. A seasoned Nordic skier typically maintains an array of skis and poles, finely tuned to the two techniques and to various conditions. Nordic skiing also requires substantial equipment to keep the skis prepared for racing through a process called waxing. Waxing in Nordic skiing is a crucial process that enhances glide and grip on the snow, optimizing performance based on conditions. Skis are waxed differently for classic and skate skiing, with various types of waxes (e.g. grip wax, glide wax) ap-

plied to the base of the ski. To wax skis, skiers need specialized equipment including waxing irons, brushes, scrapers, and a variety of waxes tailored to snow temperatures and moisture levels. The process involves cleaning the ski base, applying the appropriate wax, and then either ironing or corking the wax into the base before scraping off any excess for optimal glide. Despite the inherent expense of the sport, Belmont Hill has done a great job providing equipment and funding for skiers in need, making the sport a viable option for the entire student body.

When the sport originally started at Belmont Hill, the only widely known

technique was classic skiing. As a result, all the early seasons of the sport at Belmont Hill did not include skate skiing. When the skate skiing technique was introduced to the nordic skiing stage in the mid 1880’s Belmont Hill and the then ISSA league were quick to adopt it. According to longtime head coach, Coach Kirby, the sport also included ski jumping when it was first introduced at Belmont Hill. However, ski jumping was not required to attain a champi-

onship and Belmont Hill skiers usually opted out of this additional technique due to its inherent risk and equipment requirements. After skate skiing was introduced to the Lakes Region league, each season of nordic skiing attempted to evenly balance the amount of skate and classic skiing throughout the year. In this attempt to balance the techniques and promote well rounded skiers, the yearly championship adopted a skiathlon format. The skiathalon generally begins as a classic race and requires skiers to change skis and poles at the halfway point in order to finish the race using the skate skiing technique. As a result of the Belmont Hill Nordic skiing teams exceptional coaching staff, skiers have excelled in this form of competition throughout the years, leading to the numerous team accolades listed above. When the Nordic skiing program was first introduced at Belmont Hill, all practices and races were held at the Concord Country Club. After the original league, the ISSA, drifted apart, practices moved to the Leo J. Martin Golf Course, and races moved up north. Despite the difficult competition that came as a result of switching to the New Hampshire/Vermont Lakes Region League, Belmont Hill and its golf course trained Nordic skiing team have excelled repeatedly. The team has typically practiced in Massachusetts on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays, while they travel up north for races on Wednesdays and optional practices on Saturday.

The success of the Belmont Hill Nordic team is a testament to its determined athletes and profoundly skilled coaching staff throughout the years. Despite its occasional challenges such as a lack of snow, the program has persevered, consistently securing titles and is poised to continue its success into the future under the guidance of Coach DeCaprio.

Brady Paquette ‘25

Denuclearization remains a complex issue, especially for countries like North Korea, Russia, and the United States. Nobody will doubt that the removal of nuclear weapons will increase global stability and mitigate risks. However, many argue that the possession of a nuclear arsenal can provide assurance against invasion or external aggression. As safeguarding national sovereignty is important, it can be achieved in more reassuring ways. As international tension continues to rise today, advanced military weaponry rises with it. The effects of using nuclear weapons immeasurably damage our world and increase overall threats. Why should we sit back and wait around for another nuclear war? For this reason, America and every other nuclear state should denuclearize their militaries, leading to improved international relations and economic benefits.

For many years, Israel has been set on possessing nuclear missiles, even though they have never officially acknowledged an arsenal within their military. Whether this be true, Israel’s presumed possession has influenced its relationships with surrounding Middle Eastern countries. Non-proliferation efforts and the ignoring of disarmament have grown into a concern for neighboring states. Likewise, North Korea has struggled with internal issues regarding economic hardship and diplomatic isolation. Countries such as Japan, South Korea, and even allied China have put strict sanctions on North Korea in response to their nuclear activity. Denuclearizing said militaries would help to improve international relations and could lead to a rebuilding of trust among the nations, paving the way for collaboration on future challenges such as climate change. It is also important to note the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), signed in 1968 by the US and the Soviet Union amidst the Cold War in an effort to “prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapon technology, promote cooperation in the peace-

ful uses of nuclear energy, and further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.” Fulfilling these commitments enhances international credibility and reinforces stability. Predecessors such as the US strongly influence the global security landscape, so reducing nuclear stockpiles will not only enforce international relationships, but help mitigate risk, thus fostering a more stable world.

Similarly, the world would also thrive off of denuclearization for economic reasons.

As of 2022, the US has spent roughly $4.4 billion on nuclear weapons, the highest of any country. If military technology continues to advance on this track, the US is looking to spend upwards of $750 billion over the next decade. Maintaining and modernizing weaponry is expensive. Reducing this funding could free up substantial financial resources and that could be redirected to more other important issues like healthcare, infrastructure, and education. These areas of investment focus on benefitting society rather than dividing it. Redirecting funds towards diplomacy and foreign aid could strengthen global relations and address the humanitarian crisis. Expanded relations would help to prevent warfare crises, thus reducing the need for military intervention in the first place. Denuclearization would also foster economic growth and innovation: South Korea promised to implement a relief program to aid North Korea if they committed to the dismantlement of nuclear programs. Said rewards comprise providing food, helping to modernize hospitals and medical infrastructure, and carrying out projects to help facilitate trade. By prioritizing issues focused on human well-being, nations will be able to redirect funding and overall contribute to making a more sustainable world. There are benefits to nations using nuclear weapons. However, it is simply unrealistic to weigh military power over the existence of humanity as we know it. The instability of nuclear warfare is far too perilous, thus making denuclearization a global necessity.

Maxwell Ramanathan ‘25

There is too large of a disconnect between the elderly and the majority of the population for the elderly to represent us. The average age of Congress is 58 years old, compared to the median age of Americans, which is 38 years old. Moreover, out of the 439 members of the House of Representatives, 151 of them are above the age of 65, and over half, 45, of the 100 members of the Senate are above the age of 65. Both the Republican and Democratic presidential nominees are above the age of 75, 77, and 81, respectively Many of our representatives are over the age of 75, which is concerning, seeing that the average American’s life expectancy is 77 years old. The average American should not have to worry that their leaders may die of old age at any moment. Moreover, the National Library of Medicine did a study that found that cognitive decline often occurs at ages 70 and above. We have placed our lives and well-being in the hands of people whose minds are starting to regress. There needs to be change. As our government grows older and older, an age limit for political representation seems more and more prevalent. I believe that there should be an age limit of 70 for all politicians who run for office and a 75-year-old age cap for a Supreme Court Justice before they must abdicate their position. People over 70 years old are the group most likely to get into a car crash, other than

25-year-olds. This raises the question, if we are to base who can run for office on cognitive ability, why don’t we prevent 25-year-olds from running for office? The answer is we do. To run for office as a representative, one must be over the age of 25. To run for office as a Senator, one must be over the age of 30. To run for the presidential office, one must be 35 years old. These minimums were put into place to deter people whose minds are not fully developed from running for office. However, the mind is said to fully develop in the mid to late 20s , so not only do these minimums stop anyone before that age from running for office, but the minimum to run for president is a full five years after the brain finishes developing. If there are minimums to prevent those whose minds are not at their peak capacity from running for office, surely there should be maximums to prevent those whose minds are declining from running for office. Not only are these age maximums needed to protect cognitive functionality in government, but they would also prevent politicians, such as Supreme Court Justices, from influencing Americans while on their own literal deathbed. Instead, the two men who are running for president are both above the average life expectancy and are at least seven years past the age of cognitive decline. Whoever wins will be the supreme representative of a group of people whose median age is 40 years younger than them.

Alex Laidlaw ‘25

Foreign affairs have long been a contentious topic in the United States. Early on, many favored an isolationist policy that kept America out of foreign entanglements, particularly in Europe. Later, America became more involved in global affairs, involving itself in conflicts throughout the globe. However, regardless of the era, one thing has prompted America to involve itself beyond its borders: capitalism. Under the early presidents, the US established a highly protective policy of American trade. For example, one of the young country’s first conflicts was the Quasi-War with France, a series of small naval battles between the US and France because of the French seizure of American merchant ships. Later, under the presidents of the early 20th century, America entangled itself in South American political affairs (Venezuela) and overseas (Hawaii, the Philippines, etc.), intending to protect American business people involved there. Today, the United State’s foreign policy must continue its longstanding tradition of protecting its economic interests. With capitalism being a cornerstone of American democracy, it is the government’s duty to protect it. Therefore, as the United States navigates the situation in the Middle East, it must play an active role in inhibiting the Houthi rebels’ attacks on civilian and merchant ships. The Houthi rebels pose a major threat to the global economy. Centered on the Red Sea, the group holds a prime position upstream from the Suez Canal, a waterway through which about 15% of all the world’s shipping traffic travels. Eager to retaliate against Western support for Israel, the group has unleashed constant attacks upon merchant ships heading for the canal. Having launched at least 57 attacks on vessels since November, the group has prompted shipping companies to reroute goods traveling toward Europe. In

doing this, the Houthis have thrown a wrench into the supply chain, causing factories to close and raising consumer prices. While most of the effects have been felt in Europe, the destination of most goods traveling through the Red Sea, the shockwaves sent through the supply chain system have reached America’s shores. More importantly, their attacks could have long-term effects if not stopped. According to Ryan Petersen, CEO of the supply chain management firm Flexport, year-long Houthi disruption may inflate prices by 2%.

Given the economic impact of the Houthi Rebels, the world must act to stop their attacks. Much like how the US fought against the Barbary states of Northern Africa in response to the pirating of American merchant ships during the Tripolitan War (1801-1805), the US must fight against the Houthis in response to their actions in the Red Sea. The US must make it clear that attacking the global supply chain and encroaching on American economic interests cannot be condoned no matter the circumstances. Considering that protecting American economic interests has been a core aspect of American foreign policy from the nation’s beginnings, defending against the Houthis’ attacks would merely be the US following its precedent.

Considering the United State’s duty to protect its economic interests around the globe, the government must play an active role in dealing with the Houthis’ attacks. However, the issue is far more nuanced than an economic matter. With the Israel-Hamas War raging in the Promised Land and anti-American sentiments only growing in the region, the US must be very careful with its approach to retaliation. While passivity is not an option, the government must make its measures controlled and calculated, ensuring that the government’s role as a protector of its economic interests is made clear without overstepping its boundaries.

Eli Norden ‘26

There is no room for racism in this country. Sports team names like ‘Redskins’ should not be acceptable in a nation that strives for equal opportunity for all. This name demeans a group and uses racist terminology to do so, as does their logo. Additionally, the stereotypical facepaint, headdress, garb, and dances of Chief Noc-A-Homa represented a misunderstanding of the great and diverse culture and tradition of Indigenous Peoples in North America. However, other mascots and team names, such as the Kansas City Chiefs and Atlanta Braves, represent the ideals of the great Indigenous tradition in the Americas. Native American mascots and team names should continue to exist because of the ideals they represent; however, a line must be drawn between actual representation of the ideals of a great culture and tradition and flat-out racism and cultural appropriation.

Native American mascots represent ideals that not only represent the values of Indigenous tribes, but also those of Americans of all backgrounds. A name like the Braves makes one think about a warrior willing to go into battle to fight for the sake of others. Bravery (naturally), courage, and perseverance come to my mind when I hear this team’s name. The Chiefs’ logo and name represent the ideals mentioned above, along with leadership, as chiefs are respected and listened to by all in native american cultures. As a culture of victimization becomes increasingly popular and accepted in the U.S., it is crucial to recognize that these teams lack offensive language or logos but rather ideas that all Americans can learn from.

Other groups are represented by figures regarding culture, tradition, and race, yet there is no outrage about the names and mascots of these teams. A fighting Leprechaun represents the Notre Dame Fighting Irish. The Ragin’ Cajuns is a nickname used to refer to the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s sports teams. Many far-left movements pro-

moting equal opportunity also seem to strive for equality of outcome. Normalizing victimization must end. When looking at the oppression or appropriation of a traditionally marginalized group, it is necessary to make sure that all groups are correctly represented.

Although it is clear that the majority of Native American mascots—in the current day— represent the positives of a culture that has been decreasing both in population and in the sphere of influence since colonization, something must be done to protect the racist imagery of the former Cleveland Indians or Washington Redskins logos from occurring at the high school level through professional sports broadcasted in front of millions of Americans weekly. There are two ways to combat this. First, establishing a board of knowledgeable Native Americans or experts in Indigenous culture, language, and tradition to regulate what is OK and accurately represents the good parts of a culture compared to what is racist, demeaning, and doesn’t correctly represent Native Americans. This could occur via legislation, too. Last, restrictions should be put in place at local, state, and federal logos so that all cultures are accurately represented.

Native American mascots and team names are significant parts of a long tradition of courage and leadership. Still, restrictions must be established to distinguish between accurate representation and racism. Fake news and misinformation is an issue in this nation. Whether it be regarding elections, foreign conflict, or even sports, the average internet user consumes false or skewed information seemingly constantly. For this, all cultures must be appropriately represented in mass media. For people to care about a cause, they need to understand it; Native American mascots and the ideals they help teach must be kept for people to care about bettering the Native American experience in the 21st Century.

Gavin Zug ‘25

To say there is a gambling problem in the United States is an understatement. Even for teens, gambling has never been more accessible. First, sports gambling has finally become legal in 38 U.S. states. This has heavily shifted the makeup, process, and view of gambling among gamblers and non-gamblers. According to Statistica.com, there were over 25 million sports betting users in the U.S. in 2022. In addition, this number is expected to add over 10 million bettors by 2025. Many gamblers have shifted betting to sports due to the view on it in the U.S. While gambling, such as blackjack, slots, and craps, is portrayed as true luck; sports betting is slightly less so. For example, sports betting and stocks have a lot in common. Like studying your stocks, you can watch, read, and learn about the teams you bet on. Further, these bets can be longer-term and short-term, just like stocks. Sports users can bet on who will win a championship, similar to a long-term stock. However, they can also bet on points scored or who will cover a game’s spread, similar to day trading stocks. With these ideas, the U.S.’s culture and view on gambling for sports betting have changed significantly. Also, just like stocks, gambling sensations have appeared online with the recent changes in sports betting. For example, Sean Perry, a casino and sports betting sensation, correctly predicted the Super Bowl winner for five years. This also prompts more people to join the sports betting culture, seeing big wins from just regular people.

There is a real problem on the topic of teens. While big businesses are doing a solid job of keeping teens off their platforms, the new culture has encouraged teens to gamble offline with friends and others for small but large wagers. Big brands such as DraftKings, Fanduel, and Bet MGM require an ID and your Social Security number. This secures their platforms in order to attempt to slow down the rush of teen gambling. Unfortunately, with these restrictions on apps, teens and young adults have turned to betting with each other or even illegal sportsbooks. Sports betting is a problem, but not nearly as much as casino gambling.

Casino gambling is more of an oldtime type of betting. Games such as poker, blackjack, slots, and craps have revolutionized with the times. Big lights, unique colors, and big chips in casinos are all part of the plan to make sure the house wins. This has become an epidemic in the U.S. and is not adequately addressed. A few ways to fix this problem would be to add regulations for casinos, such as a maximum amount of money a person can bet, depending on their worth. Another way to fix this problem would be to change the gambling age law to 25; this would allow the young teenage brain to fully develop before making irresponsible decisions with their money. Finally, just raising awareness of the gambling epidemic through government money would help to bring awareness to the problem even more in the U.S. Overall, casinos are a much worse problem for gambling, but there are ways to fix this problem slowly.

Kevin Weldon ‘24

Gambling is perhaps the most normalized of all addictions. While addiction to substances like hard drugs and alcohol is taken extraordinarily seriously, with massive historical and current reactions to the issues, gambling can just as easily destroy a person’s life, yet is seeing the opposite effect. Policies such as prohibition and the War on Drugs prove that the US has never taken addiction lightly, and gambling was no exception for the vast majority of our nation’s history. For decades gambling was reduced to small-scale bets among friends by heavy regulation, while any larger scale gambling was localized to the remote city of Las Vegas, Nevada. However, with the advent of technological revolution and online betting, gambling regulation everywhere has taken a hit and seems to be buckling under the pressure of a massively growing market. Thus, not yet a crisis, a gambling epidemic is sweeping the US, and it is mostly unopposed or is even supported by policy-makers.

DraftKings and Fanduel are the two largest online betting websites, and they have skyrocketed in popularity over the last decade. Like any addictive activity, gambling gives a much sought-after emotional feeling, known as the “gambler’s high,” where a rush of excitement in the form of adrenaline floods the body. This feeling either results in a crushing defeat or euphoric feeling when they gamble either busts or pays off, and the cycle quickly becomes dangerous. Large online betting companies understand this feeling well, and have been weaponizing it against the public. Oftentimes, commercials will offer hundreds of dollars in “bonus bets” if an initial wager is placed, since these corporations understand that the biggest barrier of entry is the creation of an account, and try to bribe users with offers of free money. They depend upon the fact that once these “bonus bets” expire, users will

continue to gamble, and unfortunately, they overwhelmingly are correct.

The problem is facing no meaningful regulation, but is rapidly gaining popularity among the youth. Especially in sports gambling, influential people are increasingly placing massive wagers, popular social media companies like Barstool Sports and ESPN are heavily promoting gambling, and gambling figures – over/under lines, points favored, and odds – have increasingly become part of the sports spectating experience and stat lines. This is especially catastrophic for the American youth, who have easy access to gambling and are much more likely to become addicted and not understand the true stakes of gambling large amounts of money.

If this evidence is not convincing enough, Australia presents a cautionary tale. The nation underwent a similar gambling boom which never faced pushback decades ago, and the results have been clear. The Guardian claims that Australia youths as young as 10 years old have become addicted to gambling, and the nation has the largest per capita losses in the world, which total up to an estimated twenty-five billion dollars lost every year. This is the future of the United States if we do not act swiftly. Staunch regulations, requiring identification and proof of age must be instituted to combat underage gambling. Furthermore, enticement of non-gamblers with “deals” should be outlawed, as well as a raise in the age requirement for gambling. Online gambling should face strict restrictions, such as limiting bets over a certain amount, stopping users who exhibit destructive gambling habits, and reducing the role it can play in media and national events. Most essentially, it is critical that gambling be recognized and acknowledged by the public for what it is – dangerous and detrimental – and the normalization of it, especially in the sports world, must be altered or stopped altogether.

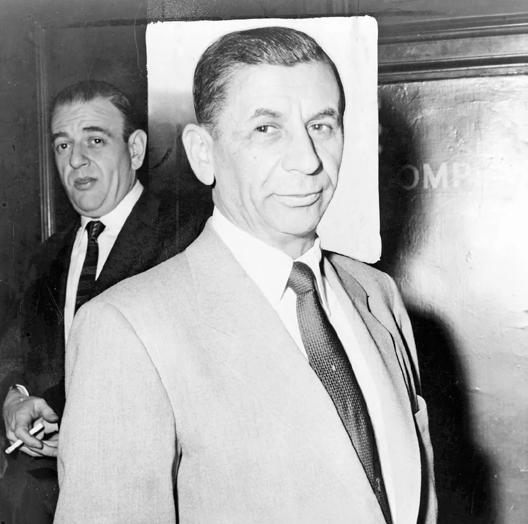

Noah Farb ‘24

Introduction:

“Michael, we’re bigger than U.S. Steel,” said Hyman Roth to Michael Corleone, head of the Corleone crime family in Martin Scorsese’s Academy Award Winning Godfather trilogy.1 Roth was a fictional character based on Meyer Lansky,2 one of the most influential Jewish gangsters in American history who, the year before his death at the age of 80, was awarded a place on the inaugural 1982 Forbes 400 list of richest Americans.3 In addition to the Lansky based character’s appearance in the Godfather trilogy, American Jewish gangsters were featured in several high-profile Hollywood films over the past 50 years including, Mobsters, Bugsy, Casino, Billy Bathgate, Once Upon a Time in America, and most recently the 2021 film Lansky. 4

While the provenance of Lansky/Roth “U.S. Steel” quote comparing mob earnings and influence to the massive U.S. Steel corporation is murky, Lansky and his longtime partner Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel were undisputedly two of the most well-known American organized crime figures of their time. Despite Lansky and Siegel’s notoriety, the widespread existence of Jewish organized crime in early to mid-20th century America is little known by most Americans, and even less so while it was current.5 Few Americans are familiar with Lansky and Siegal’s Jewish gangster contemporaries, some of whom were among the most powerful and feared men of their time. For example, Murder Inc., was a brutal murderfor-hire organization operating throughout

the 1930s across the United States and was suspected of being involved in hundreds of murders. Murder Inc. sometimes charged as little as $1 for a “hit,” worth around $18 to $25 today,6 and was led by Louis “Lepke” Buchalter,7 a Jewish mobster who, to date, is the only American organized crime figure ever to have been executed by the government.8 Other notables dot the archives. Moe Dalitz was a Jewish gangster involved in bootlegging and illegal gambling who started his underworld career as an associate of Detroit’s much feared Purple Gang. Along with Lansky, Dalitz also made it onto the Forbes’ inaugural 400 Richest Americans list in 1982, based on his ownership of Las Vegas casinos, placing him ahead of Star Wars creator George Lucas and future President Donald Trump.9

Starting with grit, the desire to improve their status and financial position and a “nothing to lose” mentality, Lansky, Siegel, Buchalter, and Dalitz are just a few examples of American Jewish organized crime figures, composed mainly of first-generation immigrants or the children of recent immigrants, who were active underworld figures during the early to mid-20th century.

While the financial success of many Jewish organized crime figures during this period was spectacular, surprisingly few Jewish gangsters passed on their criminal legacy to subsequent generations. American Jewish organized crime was almost exclusively a single generation phenomenon and in many respects a story of assimilation and immigrant success, albeit often through distasteful, unscrupulous, and occasionally violent means.

Few of the prominent American Jewish organized crime figures of that period had successors of any kind, and because there was seemingly no familial desire on the part of these individuals to carry on the criminal activities, no legacies endured. Improving economic conditions gave second and third generation American Jewish families the opportunity to leave the densely populated “immigrant enclaves” which fostered crime and gangsterism, to the suburbs.10 The legalization of widespread alcohol distribution and sale along with legal casino gambling in Nevada in the 1930’s opened pathways for many Jewish gangsters to sustainably legitimize their newfound wealth.11 Increased government attention on organized crime led to many former gangsters turning “legit,” being weeded out of the “business,” or for those that could, retiring. In short, the sudden disappearance of American Jewish organized crime of the early to mid-20th century was the result of a lack of familial legacy, improving economic conditions, the ability to go “legit” through legalized industries, sand a sustained government crackdown on organized crime.

Jews have been present in the United States since the colonial era; the first confirmed Jewish immigrant community dates to the Dutch merchant ship Valck landing in New Amsterdam in 1654. America’s Jewish population grew slowly from the colony’s inception through the late 1800’s, primarily through immigration to eastern coastal areas.12 By the end of the 1870s, a census commissioned by the Board of Delegates of American Israelites estimated the American Jewish population at 230,000,13 ess than 0.5% of the American population of approximately 50,000,000 in 1880.14 It wasn’t until over 200 years after the arrival of the Valck in the

1880’s that the first reports of American Jewish organized crime emerged.15 Jews were viewed as an “other” by the majority Anglo-Saxon protestant population and faced heavy discrimination in the colonies through the colonial era and early years of the United States. In Maryland, Jews were barred religious freedom under the Maryland Toleration Act of 1649 and did not receive religious toleration until the passing of the “Jew Bill” in 1826.16 Prior to 1880, The American Jewish community was composed primarily of Russian and German immigrants who kept many of their familial traditions but by the mid 1800s were reasonably assimilated into American society. Starting int the 1880’s and throughout the next four and a half decades Jewish immigration to America expanded dramatically, coincident with increasingly anti-Jewish political policies and social views across Eastern Europe17 when anti-Jewish pogroms became common.18 By 1924, some estimates placed the number of American Jews at 4,500,000,19 or approximately 4% of the American population.20 This exponential increase in America’s Jewish population over the 1880-1924 period was the result of mass emigration of Jews out of Eastern Europe chiefly due to increased anti-Jewish sentiment, poor living conditions,21 and America’s open immigration policy for Europians.22

World War I significantly slowed most European, and therefore Jewish, immigration to the United States but the ultimate and lasting cause of reduced Jewish migration to America were the numerous forms of anti-immigration legislation passed by Congress in 1917, 1921, and 1924.23 The Immigration Act of 1924 was particularly onerous; it placed severe restrictions on arrivals into the United States that effectively forced potential immigrants to prove their admissibility under immigration laws rather than for immigration officials to prove inadmissibility, as

had been the policy in the past. The acts placed admission quotas on ethnic groups based on ethnic group population numbers of 1890 and forced potential immigrants needed to prove their future usefulness to American society to immigration officers by showcasing a skill or trade instead of simply passing a health exam, as was the policy before.24 Post-1924, Jewish immigration to the United States slowed to about 10,000 per year,25 and these restrictions stayed in place until the second half of the 1940s.26

From 1880-1920, the foreign-born population of America doubled from seven to fourteen million; immigrants made up over 13% of the country’s total population in 1920.27 American immigration data from that period indicates that nearly all immigrants were impoverished upon arrival with almost half not having a previous occupation. Most of them were also deemed “unskilled,”28 and less than 40,000 of 200,000 immigrants arriving between July 1st to December 31st were considered “skilled” or “professional.”29 Many of these immigrants had been expelled from their home country as “undesirables” for reasons such as criminality or medical concerns.30

Because of limited resources and familial connections, new arrivals to America typically flocked to densely populated urban neighborhoods where they felt a cultural connection, providing them with a sense of community and helping them with employment and other essential needs. These immigration patterns created communities such as New York’s Little Italy and San Francisco’s Chinatown; communities that were distinct from mainstream populations across the United States. In most cases, these neighborhoods served as transitional waystations for immigrants looking to move upward in society. Most migrants looked to raise their economic status and move out of the “immigrant enclaves.” where they initially settled upon arrival.31 The Jewish immigrant enclaves were no different than any other poor immigrant communities of the late 19th and early

20th century. Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives dedicated a chapter to the “Jewtown” of New York. In the chapter, Riis discusses the brutal living conditions of the New York Jewish community in the late 1880s, “It is said that nowhere in the world are so many people

crowded together on a square mile as here.”32 Different areas of the neighborhood reached over 300,000 people per square mile. Living in these areas was unhospitable. Poverty was widespread, and according to Riis, “life itself is of little value compared with even the leanest bank account.”33 Riis also mentions how “over and over again” he had seen “Polish or Russian Jews deliberately starving themselves to the point of physical exhaustion”34 to save miniscule amounts of money. Gangsterism presented a potential way out of these inhumane conditions and money young Jewish boys of the era jumped on the opportunity.35

The 14 million foreign-born immigrants who entered the United States between 18801920 birthed 23 million children36 in the years after their migration, creating a massive influx of first-generation Americans. Children of immigrants typically had higher crime rates than their parents because of a multitude of factors, including dense population, broken

homes, poor socioeconomic standing, mixing of many different ethnicities and cultures, few community guides, and scarce educational opportunities for first generation Americans regardless of culture or nationality. The children of poor immigrants in urban areas, especially boys, often formed gangs to rebel against the discomfort of continued poverty, leading them into lives of delinquency and crime.37 Multiple studies from the 1920s and 1930s affirm across generations, ages, ethnicities, and races, crime rates are statistically higher in impoverished communities when compared to wealthier areas.38 A 1937 essay in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology observed, “all boys of the same socio-economic class, whether of foreign, negro, or native white parentage, enter into gangs with equal facility.”39 One result of the higher crime rates in densely populated, impoverished immigrant communities was the emergence of organized crime syndicates. As defined by the FBI, organized crime is “any group having some manner of a formalized structure and whose primary objective is to obtain money through illegal activities.”40 Chiefly due to the proximity of people living in immigrant enclaves along with shared culture and customs of the people within those groups, the earliest organized crime groups were typically centered around a single race or ethnicity.

Ethnic based criminal organizations often profited off illicit activities often including prohibition-era alcohol trafficking, gambling rings, loan sharking, racketeering, political and legal corruption, extortion, and murder for hire. Organized crime provided a path to move up in status and wealth and helped ease assimilation into American culture and society.41 Ethnic enclaves such as New York’s Lower East Side Jewish “ghetto” and Chicago’s Lower West Side Little Italy were breeding grounds for gangs. During the 1920s, Chicago saw the emergence of, Jewish, Irish, Italian, Black, Mexican, and Chinese crime groups.42 Organized crime was a way for many to sustain a living in underprivileged areas. In Chicago in the 1930s, over ½ of Blacks with a net worth over $100,000 were organized crime bosses.43 Money, and the freedom money al-

lows, equates to power in many modern societies. Organized crime was one way to sustain a living in underprivileged areas, and many of the most successful and powerful members of impoverished immigrant communities in early to mid-20th century America were crime bosses.44 The money and power gained through organized crime provided opportunities for those looking to move out of their immigrant enclaves and opened opportunities not available to them elsewhere.45

In the early to mid-20th century, American Jews were rarely viewed as violent criminals by the public; this changed with the murder of Jewish bookmaker Herman Rosenthal in 1912. In the early 1900s, Jewish criminality was often believed to be concentrated around nonviolent offenses, such as fraud or arson. Prior to Rosenthal’s murder, he had announced he was planning to reveal the names of several prominent NYPD officers involved in criminal gambling schemes.46 The subsequent judicial investigation into his murder and a New York Times piece titled “The Rosenthal Murder Case”47 opened the eyes of the New York public to the existence and expansive reach of powerful Jewish organized crime figures. Gang members such as crime boss William “Big Jack Zelig” Alberts, Rosenthal’s murderers, Harry “Gyp the Blood” Horowitz, and Lefty Rosenberg were all pursued and later convicted by the NYPD, revealing to the police force the power and expansiveness of the Jewish Lower East Side Gang.48

Jewish gangsters of the first two decades of the 1900s, like the men mentioned above were violent criminals, yet most were not well known outside of their own communities. These gangsters were poor immigrant children using organized crime to make a living. They operated gambling houses, prostitution rings, and preyed on fellow members of their Jewish community in racketeering schemes while simultaneously defending them from other ethnic gangs.49 These men lived in the Jewish immigrant neighborhoods such as New York’s Lower East Side, Crown Heights, and Brownsville, or Detroit’s Hastings neigh-

borhood, nicknamed “New Jerusalem,” or “the Ghetto.”50 While few personal connections existed between Jewish criminal groups, these men led to the later and more well-known wave of New York area Jewish gangsters, which included the likes of Arnold Rothstein, Arthur “Dutch Schultz” Flegenheimer, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, and Abe “Longy” Zwillman.” Jewish organized crime existed in almost every major American city in the early to mid-20th century.51

The 18th Amendment’s ratification on January 16, 1919, ushered in the era of Prohibition, outlawing the sale of alcohol in the United States. Pre-Prohibition, most organized crime consisted of small ethnic gangs in neighborhoods or cities engaging in small street level crime. Serving as a prime example of the law of unintended consequences, Prohibition quickly became organized crime’s golden ticket.52 The rise in the influence and profitability of organized crime coincided with the 1880-1924 mass migration of Eastern European Jews to America. Prohibition created conditions that allowed Jewish gangsters to earn never-before imagined profit from the newly illegal alcohol distribution industry. A disproportionate number of Jewish immigrants became involved in various aspects of bootlegging operations, both for its profitability, and possibly due to the Jewish immigrant’s history as alcohol producers and distributors in Eastern Europe.53

During the early to mid-20th century, Jews were overrepresented as a percent of their population in organized criminal activity. Nationwide, they accounted for half of the major bootleggers during the Prohibition era from 1919-1933,54 even though less than 4% of Americans in 1929 were Jewish.55 In Detroit, 3.5% of the population was Jewish, yet one of the most prominent gangs was the exceptionally brutal all-Jewish Purple Gang, recruited from the poor children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. The gang reached its peak during Prohibition; the Detroit police connected the Purples with over 500 murders, more than believed killed by the infamous Capone Mob.56 In nearby Chicago during the late 1920s, 20% of organized crime bosses were Jewish,57

even though Jews made up less than 11% of Chicago’s population in 1927.58 While often similar, Jewish gangsters across the country were active in a variety of criminal activities. Jewish mobsters in Chicago were most heavily involved with gambling and pimping rather than bootlegging, which was the most common illegal activity for Jewish gangsters in most other cities across America.59

While the unquestionable peak of American Jewish gangsterism was during prohibition,60 the reach of Jewish organized crime in America did not completely falter with the passage of the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition in 1933.61 In the late 1930s, Jewish mobsters across the country led the charge to fight against American Nazi Bund groups and their sympathizers when the legal methods of the Jewish establishment failed due to free speech protections. New York judge and former congressman Nathan Perlman sought Meyer Lansky’s help after diplomatic efforts to shut down the Bundist rallies failed. Lansky and a few other Jewish underworld associates infiltrated a meeting and effectively shut the meeting down. Jewish mobsters actively worked to curtail Nazi rallies in New York continued for over a year.62 During the post-World War II era, organized crime controlled parts of the New York and Los Angeles ports. In the late 1940s, Jewish gangsters working these ports were involved in the “misplacement” of military weapons meant to be shipped to Arab nations while ensuring the safe passage for similar weapons destined for Israel in preparation for the Israeli War of Independence.63 Jewish gangsters used their criminality in as a form of geopolitical activism with wide reaching effects all over the world.

Despite their disproportionate involvement in American organized criminal activity, American Jewish gangsters did not build sustainable criminal enterprises. With few exceptions, Jewish gangsters began to disappear through the 1950’s. By the middle of the 20th century, almost all references to American Jewish organized crime in popular culture, political discussions, and newspaper headlines had ceased to exist64 and there was almost no

large scale Jewish organized crime beyond the early 1960’s to carry on the legacy of the Jewish gangsters of the early to mid-20th century.

American Jewish organized crime was principally a product of the American immigrant experience. Only a handful of Jewish gangsters born after the major Jewish immigration wave of 1880-1924 became well-known organized crime figures. Of the 34 Jewish gangsters mentioned in the book The Mafia Encyclopedia, only three were born after 1915.65 While not comprehensive, the book profiles many of the most notorious Jewish gangsters and is illustrative of the steep drop in American Jewish gangsterism after the onerous immigration law changes during and after World War I.66 A major contributing factor to the decline of Jewish gangsterism was the lack of familial legacy. Many Italian organized crime figures kept control of their operations through tight familial relations. At the infamous Mafia “Apalachin Meeting,” held at the country estate of Joe “The Barber” Barbara in 1957 in upstate New York, of the more than 60 organized crime figures attending, more than half had family connections to each other according to data gathered by a FBI raid.

Although Italian-American organized crime figures may have attempted to steer their children away from gangsterism as did their Jewish counterparts, ultimately, many Italian organized crime networks defaulted to familial succession.67

Nearly every piece of information available regarding the families of early to mid20th century Jewish gangsters points to the separation of work and home life. Los Angeles mob man Mickey Cohen, who worked primarily in extortion rackets and gambling,68 wrote in his autobiography about a “code of ethics… where one never involved wife or family in work.”69 Similar sentiments were echoed by the Geik family, who were not directly involved in organized crime, but whose family relative George Gordon participated in illegal gambling operations and was a close family friend of Charlie Workman, a member of Murder, Inc. Through the Geik family’s experiences with the mob they noticed “there are no second-generation Jewish mobsters. Jews don’t make gangsters out of their children.”70 Jewish gangsters often worked to insure their children had the ability to pursue other occupations and lifestyles.

Children of the early to mid-20th century Jewish organized crime figures often grew up in more comfortable financial situations than their Jewish gangster immigrant or first-generation American parents, who generally came from low socioeconomic status in urban areas. Consequently, the opportunities the children of American Jewish gangsters were presented with were much broader than those of the generation that preceded them; the younger generation could become skilled tradesmen or pursue higher levels of education, something the older generation generally could not. Another contributing factor to the lack of successors was that many gangsters, both Jewish and non-Jewish, and especially the more ill-tempered and violent ones, died at a young age and therefore did not raise children. While one cannot make sweeping statements about any group without detailed analysis and data, there are numerous examples of the children of American Jewish gangsters leaving their parents legacy of crime behind

them and few counter examples.

One example of the greater opportunities afforded to second generation American Jews born to gangsters can be seen through the case of Meyer Lansky. Born Maier Suchowljansky in 1902, in Grodno, Belarus, Lansky immigrated to New York City’s Lower East Side with his parents when he was nine. In New York, Lansky grew up alongside other infamous mobsters such as Bugsy Siegel and Charles “Lucky” Luciano. With the onset of prohibition, Lansky quickly became one of the most prolific organized crime figures of his era, eventually owning truck and car rental businesses, luxury hotels, and casinos. He was also involved in many illicit ventures including bootlegging, gambling, and the murderfor-hire operation, Murder, Inc. However, Lansky preferred to stay out of violent encounters and was more focused on the business side of criminal operations. At the apex of his success, Lansky had a hand in illicit activities across the country and his enterprise reached Cuba.71

Notwithstanding all the illegal activities, Lansky worked to keep his children in the dark about the true source of his wealth. Buddy Lansky, Meyer’s eldest son, only found out about his father’s role in organized crime when he saw a photo of Meyer on the front of The New York Sun when he was 19.72 Lansky’s daughter, Sandra, a self-described “Manhattan heiress,” was 14 when she discovered her dad was a part of the mob after seeing a photo of gangster Willie Moretti dead on the floor in a newspaper article titled ‘Mob Boss Exterminated in N.J.’; Sandra had dined with her father and “Uncle Willie” the night prior.73 Before seeing the news article, she had thought her dad was a jukebox salesman. Eventually, Sandra came back to her roots and married gangster Vince Lombardo. When her father heard about the arrangement, Lansky asked Lombardo to leave his life of crime for as long as he was in a relationship with Sandra. Lombardo agreed and did not engage in organized crime for the rest of his life.74 Paul Lansky, Meyer’s younger son, attended elite New York City private school Horace Mann,75 graduated from West Point, joined the United States Air Force, and eventually became a lieutenant76

serving in Vietnam.77

Longy Zwillman was another powerful mobster who tried to ensure his family stayed out of his undesirable work life. Zwillman was born in 1905 in Newark, New Jersey, to Jewish Russian immigrants. Throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s, Zwillman was a major bootlegger and racketeer, building relationships with members of the Jewish and Italian underworld across the country. At one point, Zwillman controlled the majority of bootlegging operations in his home state and was often referred to as the “Al Capone of New Jersey.”78 Similarly to Lansky, Zwillman wanted his family to have no knowledge or association with the gangsterism that supported his money and power. Zwillman actively worked to secure jobs in legitimate businesses for his family members.79 His daughter, Lynn Kathryn, grew up in a comfortable life full of wealth before marrying millionaire Warren Tuttle in 1968.80

Irving “Waxey Gordon” Wexler was a major Jewish bootlegger in New York and connected to men like Lansky, Zwillman, and Arnold Rothstein. Gordon kept his family shielded from his criminal activities. His wife, Leah, a Rabbi’s daughter, was unaware of his true job until his trial for income tax evasion in 1933.81

Moe Dalitz was a prominent bootlegger in the 1920s.82 Dalitz had a son, Andrew, and a daughter, Suzanne; neither were involved with organized crime.83 Sol “Red” Steinhardt was a jewel smuggler and gambler operating in similar circles to Meyer Lansky in New York. Steinhardt’s son, Michael, is a retired billionaire hedge fund manager, far from a fedora wearing gangster.84

Consciously pushing one’s children away from one’s business is not the only way to keep children from entering a similar lifestyle. Many Jewish gangsters of the early to mid-20th century lived violent lives, died young, and did not raise children, robbing them of the ability to potentially lead family members into gangsterism. Of a Wikipedia list of 69 prominent Jewish gangsters, 27 are believed to have died before the age of 40.85

An example of this pattern of early death was Detroit’s Purple Gang. The Purple

Gang was formed in the early 1920s with the merging of two rival predominantly Jewish gangs that operated bootlegging and protection racketeering. By 1928, the gang had become known for its ruthlessness and had reached a peak of 50 members. Over the next ten years many of the leaders of the Purple Gang were systematically murdered by rival criminal syndicates. In July of 1929, Irving Shapiro of the Purple Gang was shot in the back of the head four times. In October of the same year, Ziggy Selbin, another gang member, was found dead on the street at the age of 19. In 1933, Abe Axler, and Eddie Fletcher, two of surviving Purple Gang members, were found dead in the back of Axler’s car. Harry Shore of the Purple Gang “disappeared” in 1935, never to be seen again and in 1937, Harry Millman, one of the last remaining members of the gang was killed in a cocktail bar during dinner.86 None of these men were able to “teach” future family members their trade.

Gangsters did not only die from systematic killing sprees. Many died from one-off hits. Jewish gangster Arnold Rothstein, the man who is believed to have conceived the infamous 1919 “Black Sox” scandal along with being embroiled with many bootlegging and gambling operations, was gunned down in November 1928.87 Prolific bootlegger Dutch Schultz was murdered along with three of his associates in a restaurant in 1935 by Jewish mobster Charlie Workman.88 Perhaps the most famous Jewish gangster of all, hitman turned entertainment mogul Bugsy Siegel was killed at his home in 1947 in Beverly Hills.89 These are just a few of the many of murdered Jewish gangsters who died as a result of their underworld activities.

In most cases, Jewish crime figures, even if they were working with others, were solo actors acting for themselves. Jewish organized crime rarely involved large scale all-Jewish organizations formal structures, with Detroit’s Purple Gang being the only long-term example, and even they collapsed after almost two decades of prominence. This contrasts with some of the other ethnic organized crime groups of the early to mid-20th century, most conspicuously the Italian Mafia. Due to the

Mafia’s strict hierarchical structure of family-based groups with the Don, Underboss, and Consigliere at the top, and Soldiers and Associates at the bottom, men were continuously being groomed to be future leaders to move up the ranks. Often, to keep control of organization, only trusted members could achieve positions of power. This led to Italian mafiosos training family members to one day lead the Mafia “family.”90 Because of the familial based operations, Jewish gangsters, even if they were associated with or collaborated extensively with Italian crime groups, rarely reached prominent positions of power within Mafia families, and therefore did not have an opportunity to place their children into leadership roles in those organized crime groups, dissuading them from pushing their kids into the business of organized crime.

Without a tradition of familial legacies, American Jewish gangsterism typically did not last beyond one generation, with the premature deaths of many Jewish gangsters exacerbating this trend. The result of Jewish gangsterism being a typically one generation phenomenon placed an expiry date on how long widespread American Jewish gangsterism could exist.

A major contributing factor to the rise of American Jewish organized crime in the early 20th century were the poor living conditions and fragile socioeconomic status of the immigrant neighborhoods that served as home to the newly arrived Eastern European Jews and their children. For some, gangsterism presented an attainable way to make a living, move out of the slums, and accelerate assimilation into American society.91 With the passing of the Immigration Act of 1924, the large influx of Jewish immigration into America had effectively ceased.92 In part by the 1940’s, and even more so through the 1950s and 1960s, there were no longer large groups of young, poor, Jewish immigrant children standing by ready to take on the metaphorical torch of the American Jewish gangster.

Starting in the late 1930’s, the United

States entered a decades-long economic expansion as the country started to curtail the negative effects of the Great Depression and headed into World War II. Using Real GDP, a stat meant to compare GDP across years by accounting for inflation, America’s economy finally reached the pre-stock market crash levels in 1938. By the end of World War II in 1945, America’s economy had a Real GDP of 2330.2, over twice of the 1929 value of 1110.2.93 This explosion in economic power allowed many families living in crowded urban centers to uproot themselves and migrate to single family homes in the suburbs94 to places like Levittown, a post-World War II mass-produced suburban housing system on Long Island, New York, meant to help army veterans find housing. Levittown also had developments in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Puerto Rico.95 President Hoover’s claim of a chicken in every pot and car in every garage was finally coming to fruition. Jewish families followed this suburban revolution, mainly propelled by a significant increase in income from their impoverished immigrant beginnings and a shift in the types of jobs available to Jews.

Upon arriving in America, poor immigrant Jews were often only able to obtain the less desirable jobs in which they had prior experience from Europe, such as pushcart peddlers or labor jobs in garment factories. Employment programs created by FDR’s New Deal and the need for both soldiers and other jobs within the war and defense industries opened doors to formerly unattainable positions for American Jews.96 By 1957, Jews on average were making 136% of median income among men, and 145% of median income among women. In an incredibly short period of time, American Jews rose from impoverished lower-class Americans to making more income than the average citizen. The children of these immigrants were growing up comfortably financially, with no need or urge to resort to gangsterism.97

The changing social views of Jews in America were predominantly caused by the horrors of the Holocaust. As the American public became more aware of the atrocities committed against Jews in Europe, they soft-

ened their views towards a people who they started to view as “white,” in contrast to the continued horrible treatment of Americans of other races in many places in the country at the time. Pre-World War II, 64% percent of Americans identified as antisemites; by 1951 this dropped to only 16% of Americans.98 Within government, the presidencies of FDR and Harry Truman were significantly more pro-Jewish than ever before. FDR supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine and appointed a Jew to the Supreme Court;99 Truman was the first major world leader to officially recognize Israel as a Jewish state.100 One of the main reasons for Jewish gangsterism was a means of assimilation, and with changing social views the need to become a gangster for assimilation was no longer needed.

During and after World War II, Jewish families flocked to the suburbs as living outside of cities became affordable for middle-class Americans.101 The ability to move to the suburbs exemplified assimilation as it proved Jews were able to rise above their former place as impoverished outsiders. Over 500,000 American Jews served in World War II102 and upon their return they became eligible for GI benefits helping them to secure low-mortgage rates and to pursue the “American Dream.” In the past, Jews had often been barred from living in certain areas, but the 1948 Supreme Court Case Shelley v. Kraemer banning “restrictive residential covenants,” changing social views of Jews, and increasing numbers of communities built by post-World War II developers that permitted American Jews.103 William Levitt, the man who envisioned Levittown, was a grandchild of Russian and Austrian Jewish immigrants. In 1960, 1/3 of the original Long Island based Levittown was populated by Jewish families.104

Jews moved from cities to the suburbs at a higher rate than non-Jewish Americans. Historian and Rabbi Arthur Hertzberg claimed that one third of all American Jews left cities for suburban areas between 1945 to 1965,105 and this statistic did not include those already living in suburban areas by this time. The massive number of American Jews moving to the suburbs post World War II, created a clear

generational distinction between these new “Suburban Jews” and their parents, the majority of whom had immigrated to America between 1880-1924. An article from 1954 describes this movement of “second-generation American Jews” moving from cities to suburbs as comparable to their parent’s generation moving from European shtetls to America itself.106 The rising economic clout and social status achieved by some American Jews during this time allowed Jews to migrate to the suburbs while also serving to diminish the pool of future Jewish gangsters. One of the main goals of Jewish teenagers and young adults falling into gangsterism was the allure of money. Not only did these suburban Jews not need the money associated with gangsterism, in the suburbs during this time few opportunities for gangsterism existed as communities were more spread out and diverse.107 The need for gangsterism within the overall American Jewish population had diminished, and therefore significantly less Jews became gangsters.

By the early 1960s, 62% of Jews between 18 and 25 attended college or graduate school. These college educated Jews no longer had as to figure out how to make ends meet while growing up in the slums of New York, Chicago, Detroit, or any other major metropolitan area. Only 22% of those student’s parents had attended college. By 1959, 78% of American Jews were deemed “white collar” or “professional” workers, which severely reduced the allure of gangsterism even among those who still lived in urban neighborhoods.108 By the 1950’s, every major American city with a sizable Jewish population experienced meaningful out migration to the suburbs, reducing the possibility of American Jewish gangsters in every major metropolitan area.

Major migrations from urban to suburban areas took place in every major American city, beginning in the 1940s and usually ending by the 1960s. Detroit, Minneapolis, Boston, New York, Cleveland, and Chicago all serve as examples of this trend. Around 85,000 Jews lived in Detroit in 1940. Jewish Detroiters were concentrated in the 12th Street, Linwood, and Dexter neighborhoods, the location of the original Purple Gang. Starting in the late 1930s

and lasting through the 1960s, the center of Detroit’s Jewish communities migrated to Oak Park and Southfield, suburbs northwest of the city center and away from the violence and illicit business of the Purples.109 In 1949, 60% of Minneapolis’s Jews, including the former major bootleggers Blumenfield brothers, lived in the urban North Side area, by 1959 over a third of them had migrated to the suburbs, specifically to nearby St. Louis Park.110 In Boston, a similar trend emerged. Into the 1950s, 90,000 Jews lived in the urban Boston neighborhoods of Mattapan, Dorchester, and Roxbury. By 1960, half of them had moved to the suburbs.111 In 1940, under 100,000 Jews lived in New York City’s suburbs. Only two decades later, in 1960, over 635,000 Jews lived in the nearby suburban Westchester county, Rockland county, and Nassau County.112 A 1980 report from the Jewish Community Federation of Cleveland stated, “in the decade of the 1940s the Cleveland Jewish community departed almost en masse from the central city to become virtually a suburban population.”113 Only 5% of Chicago’s Jewish population lived in the suburbs in 1950. By the early 1960s, this number grew to 40% of Jewish Chicagoans.114 The dense urban areas and immigrant enclaves that were once breeding grounds for gangsters now were replaced with quiet white picket fence neighborhoods. When Jewish families moved out of the decrepit conditions of the “Jewtown” as described by Jacob Riis, there was no longer large groups of Jewish boys looking to become gangsters to comfortably survive.

The impact of these large scale American Jewish migrations from cities to the suburbs cannot be understated. In the suburbs, nearly all the underlying factors contributing to American Jewish gangsterism, such as poverty, lack of education, and societal discrimination ceased to exist. By the 1960s, American Jews from all backgrounds had broadly evolved from immigrants living in impoverished communities into middle class suburbanites. With many of the underlying conditions contributing to American Jewish gangsterism of the early to mid-20th century widely eliminated, few Jewish gangster role models, and new Jewish immigrants virtual-

ly non-existent, the pool of young American Jews now susceptible to gangsterism was quite small, severely mitigating the rise of a second generation of Jewish underworld figures.

Prohibition lasted nearly 15 years, helping organized crime figures earn unimaginable wealth through illegal means. When the United States repealed Prohibition with the 21st Amendment on December 5th, 1933, bootleggers were forced to reorganize their enterprises.115 Many Jewish gangsters had amassed significant capital over the Prohibition years and used their newfound wealth to enter legal ventures, including the recently legalized casino gambling industry in Nevada. The legalization of formerly illicit industries provided many Jewish gangsters with a clear path to go “legit,” and exit gangsterism.

There are numerous examples of former bootleggers moving into legal alcohol production and distribution. Abe Rosenberg was a former bootlegger who received one of the first legal liquor licenses in New York.116 Lewis Rosenstiel was involved in a family business called Schenley Distillers Corporation that had existed prior to Prohibition. Throughout Prohibition, Schenley stayed in business as a licensed medicinal alcohol distributor. However, many thought Schenley’s medicinal business was simply a front during the Prohibition years for a very profitable bootlegging business, citing his corporation’s repeated purchase of distilleries and warehouses during that time, thereby allowing him to hold considerably more alcohol than a medicinal distributor could ever need. In 1934, as many distilleries were just beginning to transition to legal businesses, Schenley reported over $40 million of legal alcohol sales, equivalent to nearly $900 million in 2023 dollars. Longy Zwillman and Joe Reinfeld, Newark’s bootlegging kings, also continued to operate their formerly illicit alcohol distribution business after the repeal of Prohibition. In 1940 the two former bootleggers sold their corporation, Browne Vintners, to a larger Canadian owned alcohol distribution company called Seagram for $7.5 million, worth over $162 million to-

day.117 The repeal of Prohibition provided the opportunity for former Jewish bootleggers to own and control legal businesses while still operating the same businesses they had run during the Prohibition years, the production and distribution of alcohol.

By 1910, virtually all forms of gambling were illegal in the United States and remained so through the end of the 1920’s.118 In 1931, in an attempt to revive its economy during the Great Depression, a Nevada state bill called Assembly Bill 98, more popularly known as the “Wide Open Gambling Bill,” was passed, making it the only state with legalized casino gambling.119 In spite of its newfound legality, a host of factors including limited gaming licenses, the Great Depression economy, low population, and the rural nature of the state at the time resulted in Nevada’s casinos never taking off through the 1930’s.120 It was not until the late 1940’s after World War II and the establishment of the first few casino resort-hotels on the Las Vegas Strip that the gambling and entertainment industry in Nevada became a substantial cash flow generating business, foreshadowing the eventual economic explosion of Las Vegas in the decades to come.121

American Jewish gangsters were no strangers to running illegal gambling rings. Like bootlegging, Jews had a disproportionate impact in the criminal gambling world relative to their overall population. A Cleveland syndicate headed by Jewish underworld crime figure Moe Dalitz invested in gambling in Kentucky, Florida, and Las Vegas.122 Moe Kleinman, a Jew who also hailed from Cleveland, made his first $1 million payday in 1929, worth $17 million today, through a bootlegging operation. He quickly used his profits to buy large stakes in illegal casino projects across the country.123 Meyer Lansky was famous for his critical role in domestic gambling projects in Florida, Las Vegas, and internationally in Havana, Cuba.124 In Chicago, Al Capone’s former Jewish bootlegging manager Jack Guzik was central to gambling operations in the megapolis through the 1930s and early 1940s.125 These men, along with many others, were involved in a wide range of gambling. At the time, policy, which was a numbers game, sports betting,

and underground casino games were all popular. Although still involved in many other legal and illegal industries, legal and illegal gambling quickly became organized crime’s main source of profit after the end of prohibition, and many Jewish gangsters followed the money.126

Starting in the mid-1940s many of Jewish gangsters easily transferred their knowledge of running illegal casinos to purchase and operate legal casinos in the emerging boomtown of Las Vegas. Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky, and two other Jewish mobsters, Gus Greenbaum and Moe Sedway, purchased the El Cortez Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas in 1945.127 Soon after, in December 1946, an investment from the same group enabled Bugsy Siegel to open the Flamingo resort casino. Siegel dreamed of creating a spectacle unlike any of the existing casino hotels in Las Vegas at the time. Unfortunately for him, Siegel did not get to see his dream flourish; he was murdered in 1947. Soon after his death, the Flamingo was taken over by Greenbaum, Sedway, and Morris Rosen, all Jewish organized crime figures. With the sale of the Flamingo for $9 million in 1954, worth $100 million today, these gangsters made off with a $3 million profit, worth $33 million today.128 With help from outside investors including the Las Vegas division of the Teamsters union,129 the former members of the defunct Cleveland Jewish Syndicate, led by Moe Dalitz, Moe Kleinman, Sam Tucker, and Louis Rothkop, bought a majority share and control in the Desert Inn, a resort casino that opened in 1950. Through his role at the Desert Inn and other casinos in Las Vegas, reformed gangster Dalitz earned the nickname “The Godfather of Las Vegas” and exerted influence on many new projects in the city through the 1970’s.130

While not all Jewish gangsters moved from bootlegging into either legal alcohol distribution or gambling, many of the most well-off Jewish mob men who had the capital to do so allocated at least a portion of their assets into the casino and or entertainment industries.131 This allowed them to continue earning strong returns while providing them with a convenient cover for past or possibly

current illicit activities, helping to shield them from criminal punishment. The now-legal industries of alcohol sale and distribution along with legalized casino gambling in Nevada provided easy outs for Jewish gangsters to exit illicit businesses.

The ratification of the 18th Amendment and the implementation of Prohibition began the recurring theme of government policies having massive ramifications within the world of organized crime. The resulting financial windfall associated with the new legislation resulted in gangs of differing ethnicities putting aside their long-standing rivalries to achieve maximum profit for all groups.132 Changing government policies and attention on organized crime allowed for both the rise of Jewish gangsters as a dominant force in the criminal underworld and caused their fall due to more aggressive law enforcement action increasing the difficulty and risk of engaging in underworld activities.

In the early to mid-20th century, local and federal government action had a massive effect on the ups and down of organized crime through legalizing formerly illegal industries, leading to the exodus from organized crime of many of the leading bootleggers and gamblers.133 At the same time, increased effectiveness at stopping organized crime nationwide driven by increased federal investment worked to take down those who chose to participate in illegal activities.134

In the beginnings of Prohibition-era organized crime, there was little federal coverage or attention. At the local level, day to day battles between law enforcement officials and organized crime often favored the mob due to their significant power within the areas and industries they operated in. In New York, Thomas Dewey’s investigative and prosecutorial skills changed the culture and relationship between organized crime and local law enforcement. On the federal level, three major waves of federal government action led by George Wickersham in 1929, Estes Kefauver in the early 1950s, and Robert Kennedy in the early to mid 1960s, served to raise public

awareness of the societal problems caused by organized crime and slowed its growth. The tenure of many Jewish gangsters of the early to mid-20th century was stopped short prematurely due to interactions with consistently more aggressive government agents and agencies on both the local and national level, further limiting the presence of the Jewish gangsters.