6 minute read

Seeking net-zero

Gov. John Bel Edwards has Louisiana on a path to “netzero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, but industry officials worry change is happening too fast. BY DAVID JACOBS

ISTOCK

WHEN BATON ROUGE celebrity economist Loren Scott gave the keynote address at February’s annual meeting of the Greater Baton Rouge Industry Alliance, he not only offered his predictions about where oil and natural gas prices are headed but also treated the crowd to his thoughts on climate change.

Scott basically argued against the scientific assertion that industrial activity contributes to global warming, and that taking such misplaced concerns seriously will threaten Louisiana’s economy and our quality of life.

“We are going to totally change the way we live in this country,” Scott said. “We’re gonna visit poverty on people like you’ve never seen before because we think there are computers out there that can forecast the weather 30 years in the future.”

Set aside for a moment that climate, which deals with longterm atmospheric conditions, and weather, which describes shortterm variations, are different concepts—left unsaid in Scott’s remarks was the fact that much of his GBRIA audience, either directly or through contracts, works for companies that at least claim to take man-made climate change very seriously.

Gov. John Bel Edwards wants to put Louisiana on a path to “net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions—adding no more to the atmosphere than is taken away— by 2050. The pledge puts the state in line with the international Paris Agreement, the federal government, 25 other states and hundreds of private-sector companies.

His goal might be forgotten when Edwards is out of office in two years. But the transition away from heavy reliance on fossil fuels, though fraught with controversy, is starting to happen whether we like it or not.

If the trend continues, Louisiana can either be part of the movement, and profit from it, or get left behind. In a state where the oil-and-gas and petrochemical sectors are critically important, but diversifying the economy is desperately needed, the stakes could hardly be higher.

HEAVY LIFTING

Paul LaBonne, who manages Mississippi River pipeline operations for Air Liquide, also spoke at GBRIA’s gathering. He says his company is looking to replace internal combustion engines with electric ones and add solar power capability to its sites.

“We’re really focused on sustainability,” he says, expressing a sentiment increasingly common in the corporate world.

ExxonMobil has lobbied against emissions regulation and been accused by lawmakers, shareholders and the general public of hiding its own research tying oil to global warming.

But in January, the energy giant announced its intention to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions for its operated assets by 2050. Amazon, Ford and Unilever among others have made similar pledges.

However, nonprofit organizations NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch argue in a recent analysis that the climate pledges of 25 of the world’s largest corporations commit only to reducing their emissions by 40% on average, not 100% as suggested by their net-zero and carbon-neutral claims. Environmentalists similarly question Louisiana’s commitment to its stated goals.

Meanwhile, industry leaders, including some who participated in the task force that created Louisiana’s climate action plan, worry about moving too fast and heavy-handed regulation. The plan, released at the end of January, rests largely on three pillars: renewable electricity generation, industrial electrification, and industrial fuel switching to low- and no-carbon hydrogen.

In Louisiana, industrial greenhouse gas emissions represent 66% of the total, according to the task force’s report, which means the industrial sector would have to do much of the heavy lifting to get the state to net-zero. Though he voted to approve the plan, Louisiana Chemical Association President Greg Bowser says certain provisions could threaten some of the state’s largest employers.

For example, he argues that enforcing a net-zero industry standard as the plan proposes rather than relying on a market-based approach would simply push emitters into other states with looser regulations. Under that scenario, Louisiana would lose the jobs and the planet would lose the hoped-for benefits.

Bowser says the chemical industry already is a leader in sustainability, cutting emissions by 75% over 30 years while increasing production in the state.

“Imposing abrupt and burdensome demands for renewable energy could result in less electricity being available across the state, impacting our everyday lives and ability to meet basic needs,” he says. “Louisiana’s market should determine just how low companies’ emission thresholds should be, not state regulations.”

DON PIERSON, LED secretary

DON KADAIR

A NEW FRONTIER

In October, global industrial gas company Air Products announced plans for a multibillion dollar “clean energy” complex in Ascension Parish. The facility would produce 750 million standard cubic feet per day of “blue” hydrogen, utilizing traditional hydrocarbons like natural gas as a feedstock, while carbon dioxide generated at the facility will be captured, compressed and sequestered a mile underground at sites east of the plant, the company says.

But experts have raised questions about how “green” blue hydrogen really is, pointing to a study out of Cornell University that suggests blue hydrogen production might produce more greenhouse gas emissions than burning natural gas. Louisiana Economic Development counters with a report by Princeton University’s NetZero America that identifies hydrogen and carbon Issue Date: March 2022 Ad proof capture and sequestration as via- #2 • Please respond by e-mail or fax with your approval or minor revisions. ble tools for decarbonization. • AD WILL RUN AS IS unless approval or final revisions are received within 24 hours “This is a new frontier,” LED from receipt of this proof. A shorter timeframe will apply for tight deadlines. • Additional revisions must be requested and may be subject to production fees. Secretary Don Pierson says. “This Carefully check this ad for: CORRECT ADDRESS • CORRECT PHONE NUMBER • ANY TYPOS This ad design © Louisiana Business, Inc. 2022. All rights reserved. Phone 225-928-1700 • Fax 225-926-1329

is a transition that will take decades to move through.”

Oil and natural gas are “finite resources” that will be used “for centuries to come” as feedstocks for plastics and advanced chemicals that go into everything from home furnishings to smartphones, Pierson says. But as major automakers like General Motors and Ford put more emphasis on electric vehicles, the demand for refined fuels will decline, he says.

And thanks to automation, the oil and chemical sectors even in good times don’t employ as many people as before. But the skills developed in Louisiana’s traditional industries can cross over. An offshore wind farm has a lot in common with an oil-drilling platform, for example.

“The requisite skill sets exist in

the companies in Louisiana to ALTERNATIVE VIEW: Economist Loren Scott argues that industry is not a significant contributor take a leadership role,” Pierson says. The transition might play a to climate change and role in shaping the next generalso suggests that putting ation of industry leaders. Polls the regulatory clamps on show millennials (people born the oil and gas industry between 1981 and 1996) and with threaten Louisiana’s economy. Generation Z (born after 1996) are more concerned about global warming than their parents and grandparents. Can the oil-and-gas and petrochemical industries, which like many others are facing workforce challenges, attract talented young professionals who want to tackle the climate challenge? Cornerstone Chemical Chief Operating Officer Tom Yura, who chairs GBRIA’s board, recalls a recent conversation about wind energy and noted that someone has to build and maintain the wind turbines. “Making [young professionals] part of the solutions will get the next generation of supporters and workers and drivers, as opposed to the next generation of protesters,” Yura says.

DON KADAIR

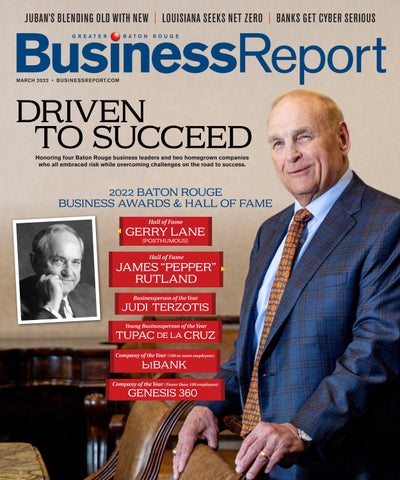

Congratulations to Pepper Rutland, LSU CM Alumni Class of 1972, on your lifetime achievement award as Hall of Fame Laureate.

Signed: “The Bert S. Turner Department of Construction Management”