16 minute read

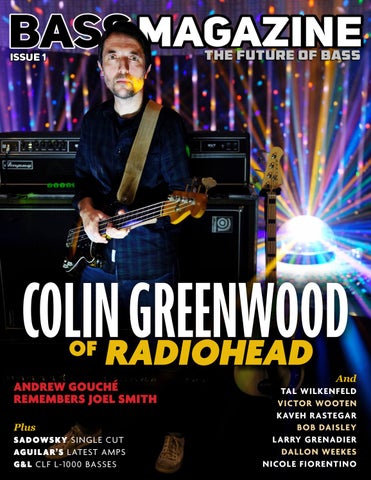

Colin Greenwood \u2013 How to Disappear Completely

By Jon D’Auria

Somewhere on a vast stage under thousands of colorful lights, rapidly flashing strobes, and bright screens suspended in the air, fixed between two drum risers and concealed within the shadows, stands Colin Greenwood. For three and a half decades, this is where he’s been so comfortably stationed — his focus rarely leaving the kick pedal of Phil Selway, moving with the rhythm and expertly delivering his bass lines. The brooding music of Radiohead is as ethereal as it is emotive, and each of the six stage members plays an equally important role in conveying such deeply impactful songs. For Greenwood, his role couldn’t suit his personality any better. He’s humble and laconic by nature, but when something enlivens him, he’s quick to articulate his thoughts on the matter with profound certainty and excitement. His bass playing is similar in style, as his foundational command steers the multitude of sounds that his bandmates create, but when the time is right, he steps out and unleashes momentous bass moments that change the entire song.

Advertisement

It would be futile and unnecessary for Greenwood to try to upstage his bandmates in the sonic spectrum of Radiohead. Frontman Thom Yorke’s stage presence alone equates to at least four performers in itself, as he attracts much of the spotlight with his energetic charisma and constant changing of instruments. Beyond that, you have Jonny Greenwood, Colin’s virtuosic younger brother, who has become a guitar icon in his own right, along with being an acclaimed movie scorer and influential multi-instrumentalist. Then you have guitarist Ed O’Brien, whose haunting and instantly recognizable guitar playing is matched evenly with his beautiful singing voice. And rounding it out is now not one but two drummers in Radiohead’s own Phil Selway and stage member Clive Deamer (Portishead, Ronnie Size, Robert Plant), who work together almost as one percussionist, kicking out polyrhythmic waves that are quick to entrance listeners. So naturally, amongst all of that, Colin’s place as a bass player is to hold all of that frenetic frequency together and use his grooves as rhythmic mile markers that keep the vehicle on track. It’s something he’s become renowned for.

But his place in Radiohead’s music is simply instinctual at this point, as his life in the band is all the 49-year-old has ever known. At age 12, a young Greenwood connected with one of his classmates and bonded over their musical likes and dislikes, and they decided to start a band of their own. That curious friend was Thom Yorke. Radiohead went on to release nine studio albums that have sold well over 30 million albums worldwide, and this year, will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. While that sounds like all of the makings of a rock-musician lifestyle, Greenwood, like his bandmates, has always kept a low profile. Living a private and modest life, he resides just outside the small university town of Oxford, England. When he’s not on the road or in the studio, he’s most commonly buried in a book or studying the transcriptions of his heroes James Jamerson, Carol Kaye, and Donald “Duck” Dunn. He’s contributed his playing to scores and albums by Yorke, his brother Jonny, and most recently he’s been performing with Egyptian songwriter Tamino, for whom Colin also recorded bass on his most recent album, Amir.

Among bass players, Greenwood is a highly adored figure that has influenced countless low-enders ranging from icons to budding stars of the next generation. His bass work on Radiohead classics like “Paranoid Android,” “15 Step,” “Morning Bell,” “I Might Be Wrong,” “Nude,” and “Karma Police” have become staples of rock players’ practice regimens. And on Radiohead’s latest album, A Moon Shaped Pool [2016], Greenwood doesn’t disappoint in the least. His expansive scale-stretching moments on songs like “Identikit,” “Decks Dark,” and “Burn the Witch” contain all of the erupting moments that we always desire from him. But for such an influential player and idol to his contemporaries and fans, Greenwood has largely remained an enigma, as he doesn’t often do interviews or make public appearances away from the stage. But luckily for us, Colin is finally stepping out of the shadows.

You’re very tasteful about your parts and when to unleash explosive lines where they fit.

Well, I love to play for the song and give it the respect that it deserves and add to it what I feel it needs. I’m in a band with a lot of other members doing a lot of things at once, so it could get muddled if we go on and step on each other’s toes here and there. I try to be patient and play for the song. One of my favorite songs that we’ve written is on our album In Rainbows called “Weird Fishes/ Arpeggi.” I had a 1978 Jazz Bass that I love because the neck is narrow and I have really small hands, so it plays beautifully for me. At the time I was really into Ray Brown’s Bass Method [Hal Leonard]; I learned all of the exercises in it, and it opened up all of the chords on the neck for me. Thom and Johnny brought in the idea for that song, and Phil had an amazing beat for it, and Ed started layer-ing his parts, and I was obsessed with those chords and scales I was learning. I started hearing all these lines over everything they were playing, so I began playing them and using the chord extensions from that book, and it gave me limitless possibilities. I wrote loads of lines for it and it went on and on, and I had to cut it down and pick sections of it to use. I had all of the shapes in my hand for the chord progressions, and it felt amazing.

“15 Step” is another example of you hanging back and then playing a song-altering riff late in the composition.

That was just my fantasy. I love soul music, and I felt that like it sounded like an old Motown kind of bass run, so I tried it and it worked. That’s also like one of our songs called “Bloom,” where I messed with a lot of bass lines and wanted to come up with something that J Dilla [late hip-hop writer and producer] would write. I came up with different lines and then I found that wonky boom, boomboom, boom-boom, boom-boom, and I tried to play it and phrase it in a way that I imagine J Dilla would have done, maybe from his album Ruff Draft [2003] or Donuts [2006]. It worked. The most exciting part about music to me is that someone might hear that and not understand how I hear it. You can translate something that you understand that they don’t get, but when they hear it, they translate it as something entirely different. I don’t think anyone listened to that part and thought about J Dilla, but that’s how I wrote it. That’s what excites me about music.

It sounds like “Bloom” could have been inspired by upright bass.

I have a Korean student upright bass that I use sometimes on “Pyramid Song,” “You and Whose Army,” and on some of my brother’s music for Bodysong [2003]. I also have a Ned Steinberger electric upright, and I feel terrible because I can’t play it that well. I need to take some lessons for that and fully learn how to translate some upright facilities to electric bass. When you watch a guy like Phil Chen play and talk about his favorite Jamerson bass lines, he goes on about how he would drop down from open notes and how it was so amazing and powerful. There’s simplicity in that genius, and there’s a sheer love of taking a song and putting your whole heart into one note.

You don’t always play economically with your left hand, and it looks like you sometimes play a line on the same string.

When I started out I was really into Joy Division, and Hooky [Peter Hook] played a lot of stuff up high and got great tones up there — so I’ve always been one to move up and down on the neck a lot. I also started off playing classical guitar, and still do, and with that you’re playing the top lines along with the bass lines, and I’ve always had the device of trying to get harmony and melody into the bass lines. Sometimes I make it too complex and too noodly, but Thom is good at putting the brakes on that. Really, I guess I try to find all of the good notes and what feels best to play. You should learn your entire fretboard and where all of the notes are, and which ones sound good where, and let that influence your playing. But you can tell that I’ve been told not to play too much for years [laughs]. Maybe that’s why it comes out in short bursts.

You also often take the function of bass beyond its common place as simply the foundation.

We toured with a band called Sparklehorse, and one of their players used to talk about how bass was the connection between the rhythm and the harmony … and now that I say that out loud, I sound like Derek Smalls [Spinal Tap] with his “lukewarm water” quote. But I think that stands very true for our instrument. If I hear some music and I connect it to something else I really like, then I try to play like that thing I’m thinking of. So as I said before, if I hear a beat or a song that reminds me of J Dilla, then I’m going to try to play something that I think J Dilla would have played over it that encapsulates what I love about him. It doesn’t end up sounding like that, because I’m not him — but that inspires it, and it becomes its own thing. We’re not limited as bass players to strictly playing root notes.

It’s great to hear that J Dilla is such an inspiration. He’s underrated as an influence on bass players.

We love hip-hop, and his work has really inspired us in what we do. You might not always hear it in our music, but that stuff weighs in heavily on it.

Which players have influenced your playing the most?

My heroes are James Jamerson and “Duck” Dunn. They’re whom I draw a lot of my inspiration from. When we first started the band, I wanted to play guitar because I had been taking guitar lessons with Thom when we were 11. Ed and Thom took the guitar spots already, so I picked up the bass and got way into a lot of that post-punk stuff like Joy Division, The Fall, and Magazine. But then as I played more, I started discovering Otis Redding, Al Green, and all of the soul music that was coming out at the time. The idea that the bass could be used to make such beautiful lines and be such a big part of music astonished me. That’s what really solidified me as a bass player.

How do you decide when to use your fingers or a pick for a song?

I use fingers mostly—I’m not great with the pick. Carol Kaye and Joe Osborn were amazing with picks. Joe Osborn is my new current hero. He was really heavy with the pick—amazing. And for fingers it’s Leroy Hodges [Stax], Joseph “Lucky“ Scott [Curtis Mayfield], and David Hood [Muscle Shoals].

How do you typically write your bass parts in sequence with the band?

On the last record I sat with our producer, Nigel Godrich, and I wrote all of my bass lines and recorded them in a series of sessions where I could focus on each individual song. Sometimes I’ll also write when we’re all standing in a room playing together. The two things I love the most are either sitting with Nigel and writing my bass lines with input from Thom and Jonny, or standing in the room and looking at everyone and working on song arrangements together in real time. That way, I can play something and Thom will have instant feedback on what he thinks is a good riff. And if you give him one thing, he’ll run with it — and before you know it, a whole song has developed. I’m trying to get my writing better and be able to notate my parts. I’ve been teaching myself to read music, and that Jameson book [Standing in the Shadows of Motown, Hal Leonard] really helps me with that.

How much of a hand do you have in the songwriting process?

Thom is the main songwriter, and it depends where it goes from there. He likes to start the process and come up with melodies and then bring them to us. Then my brother usually joins in next, and then it all unfolds from there.

A Moon Shaped Pool seemed like it spanned a lot of sessions over that two-year period.

The process had a lot of starts and stops, but the two most important times for that record came when we were in our studio in Oxford in the beginning, and Nigel wanted to do a process where we didn’t use computers at all. We recorded everything to tape and multi-track. At the time he was really into the 8-track recordings of Motown and early David Bowie albums, and he wanted to replicate that. It forces you to have to make decisions in the moment; it’s very much the opposite of having your album stored on a terabyte hard drive. Then a year later, we went to this amazing studio [La Fabrique] in the southern region of France, and we went through the previous recordings we’d done in Oxford, and we built upon all of that and finished it. Then Nigel wrapped it all up and mixed it in London.

What is Nigel’s process of capturing your bass tone?

We used to have a rehearsal space that we used, and I would always use a DI box that sounded great. But in the studio it’s all up to Nigel. I honestly don’t have any sort of idea what he’s doing to my bass until I hear [the final product]. Obviously he’s using compressors and different tools to mix it, but I leave it entirely up to him. And I’m always blown away with what he does. That’s not my area of expertise. I usually use an Ampeg or Ashdown cabinet and then all of my usual basses. He’s less keen on Jazz Basses because they can hum, so we use my P-Basses. He’s brilliant. Whatever he does he makes me sound better than I have any right to sound.

Your lines on “Identikit” really stand out.

That song was a kind of a leftover from our previous album The King of Limbs. We’d been working on using loops, and Thom has such a beautiful voice and he had recorded these three singing loops, and it became a sketch more than a song at the time. I took that to my studio at home and played around with it using my Akai MPC [recorder], and I got obsessed with it. The melodies were so beautiful. I’d send my ideas to Thom, and then he’d play piano parts on it and send it back to me, and those became the bridge part after the last verse. We worked on it for a long time, and then it became one of our new songs. Thom is a genius at finding melodies with hooks, and he came up with some for this song. The chord sequence is really straight, so I somewhat over-harmonized it a bit. When I worked on it with Nigel in France, he had me use my old P-Bass, and it sounded great on that track. It has a slight fuzz on the low end, so it sounds like a very mild distortion, and I plugged it in and started writing that part on it.

Radiohead plays in a lot of odd time signatures. Is that intentional or just naturally how you write?

I suppose the time signatures we use come out quite naturally as how write, without thinking about it. A song like “Morning Bell” from Amnesiac is interesting because it has a driving bass line on the verse, and then it gets melodic on the chorus with a harmony that I play. That’s a great example of how we work together as a band, because Thom had programmed that drum part initially and placed the bass line where it is, and I learned from that and then wrote the rest of it, including the higher-register part. It was quite the collaboration. He did something that I wouldn’t have done. That’s one of the great joys and pleasures of playing with such other brilliant musicians. My brother Johnny is really into reggae music, and he always shows me such cool dub bass parts, and I learn from those and they really inspire me.

You’re able to capture the same tone live as you do in the studio. How do you dial it in?

I like the idea that you plug into an Ampeg SVT head and it automatically sounds really good. It’s rather funny because I was only allowed to have pedals onstage recently, because previously I would stand on them accidentally and press the wrong button and all of a sudden there would be this wild distortion through the massive sound system. Now my bandmates have finally let me have pedals so long as I promise to be careful [laughs].

You’re known for playing Fender basses, but you’ve recently picked up both Sadowsky and Lakland basses.

I wanted basses that make it easier for me to play all of those faster, more difficult lines that we have. I’ve figured out that if I have a smaller, narrower neck, then I can make chord shapes with my hands. On a Precision Bass I have to fight with them more. I love the Precision’s midrange growl, and I’ve found that these new basses have that. I’ve known Roger Sadowsky for a long time, as I first met him over 20 years ago. And I got in touch with Lakland when I was in Los Angeles, and they gave me an Indonesian bass to try out, and it was the same shape that they used in making the one for Duck Dunn. When I went out on our previous American tour, I wanted to follow up with both of them. The beginning of the tour was in Chicago, so I got to go into Lakland’s workshop and explore it. And then we had seven days in New York, so I got in touch with Roger to go visit Sadowsky. I love the basses that Lakland and Sadowsky made for me, and I’m excited to use them more on tours to come.

What’s it like playing with Phil as a rhythm section after all of these years?

I’ve come to know his ankles very well after staring so intently at them for so long. I swear they haven’t aged a day [laughs]. It’s an enormous privilege to play in the same rhythm section. I love how he plays to the song, and has his own style. And now it’s such an honor to share the stage with Clive Deamer, who has always been a hero of mine. His playing with Portishead, Robert Plant, Roni Size, and Hawkwind is tremendous. What a rhythmic roll he has!

Jonny Greenwood and Phil Selway. Photo by Colin Greenwood

Your stage presence seemed to change after the Hail to the Thief era. You’re more animated during shows now.

I try to get away from just standing in the back and being “the glue.” Now I want to go over and see what Jonny’s doing. He’s amazing to watch, especially on guitar. I’m trying to have more confidence to move away from the drum position and go check out what’s happening up front. When I listen to the front-of-house mixes, the musical firing from the front three of Thom, Ed, and Jonny always amazes me. It’s quite full on being between two drummers, and I don’t want to miss all the top-line melodies and riffs flying about. More than anything else, I’ve come to enjoy being onstage with my friends. Thom sets things up with his amazing performances. He leads from the front, and he’s very supportive — he wants to get lost in the vibe onstage. It’s a very welcoming vibe, sharing that space, and that comfort and excitement transmits itself to the audience.

So what is a Radiohead show like from your perspective?

I love it when I lose myself entirely in the moment of the show. There seems to be a point about halfway [through] when band and crowd slip into the same hypnotic spell. I try not to be distracted by external thoughts, because it can derail me. I’m also trying to listen very hard to all the different sounds around me, and play to those sounds. It can be a lot more distracting live, compared to the studio: You’ve got all these dynamically lit sonic whiz-bangs going off onstage. That’s a big difference compared to having all your ducks in a row, in a balance, by Nigel Godrich in front of a mixing desk in the studio. But both are great fun, really.

What are your favorite songs to play live right now?

I always love “Weird Fishes/Arpeggi,” “Separator,” and “I Might Be Wrong.” Anything with a big singing bass line makes me happy. The trickiest songs always seem to be the simplest, with lots of space and sustained notes.

You play synth bass on songs like “Idioteque” and “Climbing Up the Walls.” How do you approach keybass?

Much like how I approach the upright bass — with great trepidation. I’m also playing loops and samples, stuff we’ve taken from the studio, and I enjoy that. I’ve explored sampling and programming a lot, and used bits and pieces of the guys’ recordings to make up the soundtrack for a documentary about a fashion designer friend of mine named Dries Van Noten [Dries, 2017]. That was great fun, but I always prefer working with other people in a band setting.

How did you first start playing bass?

When I realized the guitar spots had been taken in our band, my mum got me a black Westone DX Spectrum. I loved that bass. It was very black. I think it ended up for a while being the door prop to the old management office. I had an old Toshiba radio cassette player, and I would listen to Joy Division, Otis Redding, Cocteau Twins, Booker T., James Brown, and anything my older sister passed on: Magazine, The Fall, Joe Jackson’s Jumpin’ Jive, and I’d play along with everything. But for bassists, it was Dunn, James Brown’s players, Peter Hook, and lots of Lee “Scratch” Perry.

Growing up together and working together now, how do you and Jonny inspire and influence each other musically?

I’m very proud of Jonny’s stuff; he’s always had the music gene in him. He’s tipped me to some nice bass lines when we’re working, usually from his deep love of all things dub and reggae, like slow eighths and offbeat reggae-syncopated lines — that’s his bass style. I enjoy the unison line we play together on the song “Staircase.” In our heads we’re being Crockett and Tubbs from Miami Vice on that one: neon and Espadrilles and seersucker jackets with rolled-up sleeves and all, if that makes any sense. It’s important to entertain a fantasy when you listen to music. If you like something, it usually has affinities with something else you already love.

What are you working on in your personal practice right now?

I’m playing through songbooks from Carol Kaye, Motown, Duck Dunn, Oscar Stagnaro, and my old teacher Laurence Canty’s book. I dip into all of those, and when I’m home I try to play for one to two hours a day. I always return to Ray Brown’s book; it’s just brilliant. And I’ve learned a lot from watching our second drummer Clive and how he practices the basics and fundamentals every single day. I try to match his work ethic.

How have you evolved as a bass player over the years?

If my playing has evolved at all, it’s because I’ve vaguely kept doing the same thing for a long time. Maybe not quite Gladwell’s 10,000 hours, but more like 250. I’d like to try working with other musicians as well, just to see if I can play more regularly with a group. With Radiohead stuff, a lot of lines I play that I like come about because I’m already enthusiastic with what I hear in the others’ music, and the bass line is already formed, like a song in my mind. It can be like that with a vocal melody, a riff, or a rhythm. Really, I’m as excited and as intrigued by music as I was the day I started playing. l