6 minute read

Seeing Dreams

from Isuu_Test2

by DesignerBC

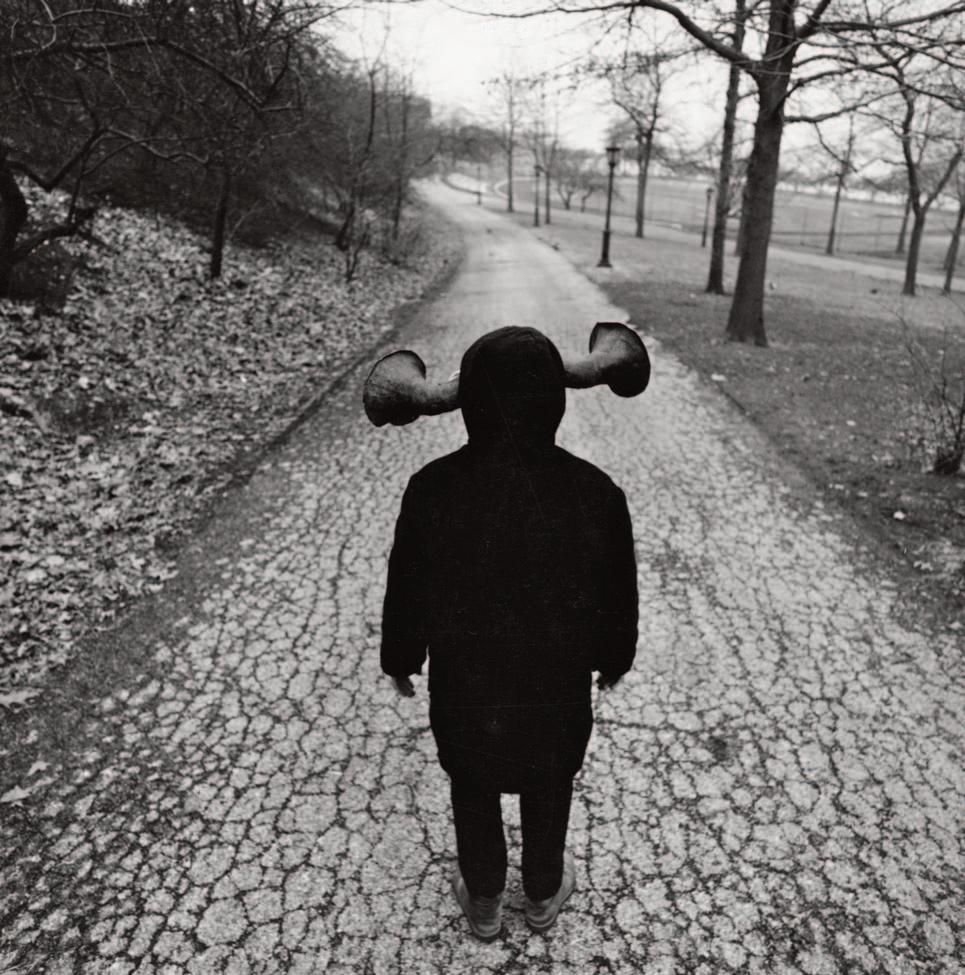

ARTHUR TRESS ’62

SEEING DREAMS

Advertisement

by Raphael Wolf ’18

Many who have lived in Annandale-on-Hudson or its environs can attest to something eerie whirring through the oak leaves at night, or hovering in a distant field, or flitting along the electrical wiring of a Gothic house. While most would dismiss such superstition, these phenomena—so insubstantial as to be just a feeling—manifest only to the few who are sensitive to them. Arthur Tress ’62 was taken by this peculiar quality of the area when, at 18, he moved upstate from Brooklyn, New York, in 1958 to study visual arts at Bard. That particular aura would work its way into his later photography.

Tress began taking photographs in elementary school, and continued to document the carnivalesque Coney Island of his youth through high school. At Bard, where film and photography had not yet been formally incorporated into the curriculum, Tress took philosophy classes with Heinrich Blücher, and produced for his Senior Project, advised by the artist Louis Shanker, a series of abstract landscape paintings. He was just one of four art majors that year, and he says the fledgling art department was “in some way an ideal situation for an independent spirit like myself.” He further speculates that being part of a new and not yet institutionalized program was part of the reason the works he produced at the time “have such an idiosyncratic buoyancy and freedom unusual in an academic situation.”

This independence also allowed Tress to experiment with the moving image. His early filmmaking explored the haunting underbelly of the Hudson Valley, and three years after graduating he presented the short film Gardens of Tivoli at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in lower Manhattan. In his Village Voice column Movie Journal, the late filmmaker, critic, and patron saint of American avant-garde cinema Jonas Mekas (brother of Adolfas, founder of the Bard film department) saw promise in the young filmmaker: “From a great number of newcomers I have seen lately, I put my bet on Arthur Tress,” whose work, he wrote, reveals “a poetic world that is his own.” This quality—the ability to articulate a distinctive world— is equally present in Tress’s still images, which he was producing at the same time. Though the photographs are often staged with models and props, they are, despite their manufactured theatricality, so uncanny they seem spontaneous and real.

In the years after he graduated, candid street photography was all the rage, while the New Topographics movement, with pictures of unpopulated industrial landscapes by the likes of Stephen Shore (Bard’s Susan Weber Professor in the Arts and director of the Photography Program), was beginning to take hold. Resisting fashion, in 1970 Tress began a series of semistaged works with children enacting their dreams. This project—Dream Collector—began when a former classmate from Bard, Richard Lewis ’58, called and proposed working together. Lewis was conducting workshops in New York City public schools that hoped to encourage children to explore the arts. The photographs that came out of this collaboration are imbued with an indescribable and unmistakable rural eeriness. Tress says Blücher’s love of myth and fable “influenced me greatly in this and later series.”

Artists, whose role is to be sensitized to the subtleties and minutiae of the world, are often the ones most receptive to the submerged presence of unusual things. For Tress it is specifically the photographer who is most attuned to these latent frequencies, engaged in “an almost ritual dance with the world whereupon his own intense response to its rhythms corresponds to his being able to predict its following certain predetermined patterns.” This ritual dance plays out in Tress’s process in Dream Collector, where he would set out with a specific dream in mind, but allow his instinct as a documentary photographer to determine the location and composition. “The photographer as magician is just someone who is more acutely aware of the subliminal ‘vibrations’ of the everyday world which can call forth hidden emotions or states,” he says. “He is, himself, totally ‘opened’ to the multiplicities of associations that are submerged behind the appearances of the objective world.”

For Tress, the photographer’s power is not just sharpened awareness of light and composition, or ability to see in fractions of a second, but an almost supernatural understanding of the subliminal world. “Incipient strangeness” is Tress’s term: strangeness that is commencing, just beginning to take form. It is this flicker of the uncanny’s emergence that Tress’s photographs magically capture. A barred owl stands inches ahead on a highway centerline; its gaze reaches through the lens, making the viewer question exactly whose image is being captured. A short body stands on a country road, pausing like the owl to absorb its surroundings, this time through large prosthetic hearing instruments growing from its head; again, the equalizing, dawn-like light renders the background trees as sketched silhouettes. A similar scene: a boy’s face pokes out from the torso of a hooded, shadowed figure hovering in the middle of a paved pathway; the boy’s untroubled countenance defies the menacing body and the large ringed knuckles resting on his chest. Another small person, this one ascending a wooden stairwell; rather than appearing absurd, the oversized face of a gnome somehow seems natural resting on a white Victorian nightgown. One might wonder what it says as it passes by. In the aftermath of a tempest of sheet music—a ballad of a dream—the hardwiring of perception is inverted: standing in the foundations of a wrecked house, one figure bows his head and reads the music on the ground, another leans against a wall and hears the building. An expanse of cracked mud that could belong to any planet or geological era sets the landscape; the young boy at the center, caked in the earth, squints at the camera unbothered, the hand- and footprints that surround him evidence of some dance or battle.

Tress has worked as a documentary photographer in France, Egypt, India, Japan, and Mexico. In 1986, the Photography Gallery of London organized Talisman, his first career retrospective, which traveled over the next four years to Oxford, England; Frankfurt, Germany; and Charlerol, Belgium. Another retrospective five years later, Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000, was mounted at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. He has produced more than 50 photo books, his work is in the collections of numerous museums, and Stanford Libraries’ Department of Special Collections acquired his archives in 2019 with the launch of its new program focused on developing a rich photographic research and teaching collection. The Getty Museum in Los Angeles recently acquired a complete set of the original Dream Collector photographs—six of which are seen here—and is planning a major exhibition and catalog for late 2022. Tress continues to make new work, capturing that incipient strangeness as only he can.

Raphael Wolf ’18 is a writer, editor, and cook based in Berlin, Germany.

Owl on Road, Big Thicket, Texas, 1975

Boy with Magic Horns, New York City, 1970

Young Boy and Hooded Figure, New York City, 1971

Girl with Mask, Rhinebeck, New York, 1975

Boy Listening to Musician, Biloxi, Mississippi, 1971

Boy in Mud, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1971