History of Baltusrol’s Golf Courses

A.W. Tillinghast’s bold vision sets the standard for golden age course design.

By Rick Wolffe

When Baltusrol Golf Club was founded in 1895, Americans were just discovering their passion for golf. There were fewer than 80 courses in the country and the United States Golf Association was not yet a year old. Nearly all of the early courses were primitive, laid out and built by men with no experience. The greens were often indistinguishable from the fairways, and the most fashionable hazards were steep earthen berms, cop bunkers, fences, and other man-made obstacles. The Old Course at Baltusrol had all of those features, but the rapid, dramatic changes to the golf course provide a perfect illustration of the trial-and-error methods that led to modern principles of course design, construction, and conditioning.

Louis Keller, founder of Baltusrol, engaged George Hunter to lay out Baltusrol’s original nine-hole course in 1895. To meet the needs of its members and to keep its place as a leading tournament site, Baltusrol expanded its course to 18 holes in 1897. Over the next two decades, the golf holes were continuously modified and improved almost to the day when work commenced on the Upper and Lower courses. This course, which today is referred to as the “Old Course,” hosted five national championships; the first being the 1901 U.S. Women’s Amateur and its last the 1915 U.S. Open. In its prime, the Old Course was widely regarded as one of America’s finest courses. Its most famous and perhaps one of the most photographed holes was the 10th, which featured what is believed to be the first “island green” in the United States.

Shortly after the 1915 U.S. Open, the Board of Governors began discussions on the merits of acquiring or building a second golf course to meet the demands of the growing membership. Over the next three years, various possibilities were explored. During this time, several newspapers reported that Baltusrol was considering a second 18-hole course to complement its highly rated and famous Old Course.

This was a dynamic time in the Club’s history. In April 1917, the U.S. entered World War I in Europe, and over 50 Baltusrol members served in the armed forces. War times were tough, and coal shortages forced the Clubhouse to close for the winter months. The Board, admirably, waived the dues for members serving in the military. The Influenza epidemic of 1918 also took its toll. But Baltusrol continued on, and its leadership pressed forward in planning a second golf course.

As time went by, the Green Committee studied various possibilities for a second golf course, but with no real option in sight. To move things along, Keller purchased or optioned several large parcels of land surrounding the Old Course. Then

True to form, the Dual Courses wasted no time establishing their reputation. In 1926, the Lower held the U.S. Amateur Championship, where George Von Elm defeated Bobby Jones in a thrilling final. The event drew rave reviews for the course’s challenge and conditioning. Tillinghast was in attendance and took immense pride in the reception of his design.

Following the Amateur, Baltusrol’s national profile soared. Additional refinements were made to both courses and preparations were made for future tournaments. Several changes were made to the Upper Course, including the construction of a second green on No. 14 to address drainage concerns on the original green. The new green was utilized during the 1936 U.S. Open on the Upper Course, but the two greens stood side-by-side for several years before the original green was removed.

The 1936 Open earned high praise for the event’s organization and course quality. The decision to hold the Open on the Upper was controversial at the time, but validated Baltusrol’s belief in the quality of its two “separate but equal” courses and set the stage for many more championships to be played on the Dual Courses.

Despite the myriad challenges Baltusrol faced in constructing the Dual Courses, their legacy endures as testament to the bold thinking that has defined the Club since its founding. Baltusrol remains the only club in America to have hosted a U.S. Open for men and women on both courses.

Championships on the Upper Course

Tony Manero captures the Upper Course’s first major championship.

By Rick Jenkins

After a stunningly successful debut of the Lower Course at the 1926 U.S. Amateur, both the Club and the USGA wanted to bring an Open to Baltusrol. The Board of Governors believed the Upper would be a worthy test, and wanted it to have the opportunity to shine on the national stage like the Lower. Quietly, and for several years, the Club had been working on improving the Upper: adding bunkers, renovating greens that drained poorly, and strengthening several holes into sterner tests.

Bobby Jones, who briefly was a Baltusrol member from 1936-37, had been asked by the USGA to opine on the Upper’s suitability as a U.S. Open venue. He liked it, but he wasn’t enamored with the finishing hole, and wanted to substitute 18 Lower – one of his favorite golf holes in all of America – for 18 Upper. This suggestion caused a tempest in a teapot, as most Board members were firmly behind playing the Upper in its entirety. But with several modifications to 18 Upper agreed on by the parties, the matter was resolved, and in late 1935 the USGA confirmed that the Open would be played entirely on the Upper. Jay Monroe, Baltusrol’s Green Chairman and General Chair for the ’36 Open, wrote in a letter to John Jackson, vice president of the USGA, that the changes to 18 Upper were being implemented in November 1935. One of those changes was moving the left greenside bunker away from the green by about 50 yards, and another was filling in the swale fronting the green in order to improve visibility for the players and allow more room for spectators.

Golf championships in that era did not require the planning we see today on such a massive scale. Preparing the golf course was the major focus, along with ticket sales. The purse for the ’36 Open was $5,000, with the winner receiving a check for $1,000.

The stars of the game in 1936 were the likes of Byron Nelson, Gene Sarazen, Henry Picard, Paul Runyan, Denny Shute, Johnny Goodman, Harry Cooper, Horton Smith, and Craig Wood, among others. The sparkling era of Bobby Jones was over, with his retirement from competitive golf in 1930. The career of Walter Hagen was winding down; the ’36 Open at Baltusrol was his last appearance in this event. Johnny Farrell, the host professional and U.S. Open champion from 1928, was in the field but did not contend. The era of Ben Hogan was just beginning; he played in the ’36 Open but missed the cut. In any event, one would not find the name Tony Manero on this list. Manero could properly be described as a “journeyman” golfer. He competed on the nascent professional tour and had some victories under his belt, but he was not a prolific winner and cer-

tainly not a “big name.” He had seven wins to his credit prior to the ’36 Open, with the biggest of them being the Westchester Open.

Manero was born in New York City in 1905, grew up in Westchester County, and learned the game in the caddie yard at Fairview Country Club in Elmsford. His closest friend from their caddie days together was Gene Sarazen, born Eugenio Saraceni. Manero was not exempt for the 1936 U.S. Open; he had to qualify. His best finish in the Open had been a tie for 19th in 1931 at Inverness. He played the sectional qualifier in Charlotte, N.C. and had to survive a playoff just to make the Open field.

At Baltusrol, the headlines became Harry Cooper, called “Lighthorse” for his fast play, Henry Picard, Denny Shute, Ray Mangrum, and the Deal Golf Club professional Vic Ghezzi. At 142 (-2) through two rounds, Manero stood in seventh place. In spite of shooting a 73 in the third round, Manero made up a little ground and stood in a tie for fourth place (-1) entering the final round. His good friend Sarazen was well back and not in contention.

Lighthorse Cooper entered the final round as the leader at -5, two strokes ahead of Ghezzi and three ahead of Shute. Cooper was an experienced winner, he was playing well, and the press was ready to crown him the champion. Born in England, Cooper moved to America at a young

age when his father, who learned the game under Old Tom Morris, accepted a head professional job in Dallas. With 36 professional wins ultimately to his credit, Cooper was considered one of the tour’s best ball strikers in the 1930s.

The ’36 Open at Baltusrol was all about the final round, played on the afternoon of Saturday, June 6. In those days, the Open’s final two rounds were played in one day, on a Saturday. The weather was fine, but the golf less so. Many of the contenders fell away, with the exception of Cooper and Manero. Picard, Shute, Mangrum, and Ghezzi, all in contention at the start of the round, went backwards; they shot a combined +20 in the final round.

Cooper was playing solidly, recording a 35 on the Upper’s front nine after eagling the first hole. He made the turn with a two-stroke lead. But Manero was playing better; he made birdies at holes 1, 4, and 8 and shot 33 going out. The contest had become a two-horse race. With a birdie on 12, Lighthorse continued his steady play. But thoughts of previous stumbles on the closing holes entered his head: The Masters just two months before, the 1927 U.S. Open at Oakmont. He would bogey three of the final five holes to leave the door open. Still, his 284 (-4) was a U.S. Open scoring record to date. He composed a telegram to tell his parents he won but waited to send it.

Tony Manero – and Gene Sarazen – had other ideas, though. Manero was playing the round of his life on the biggest stage of his life, and Sarazen was keeping him calm. Sarazen knew he was going to win. Manero made back-to-back birdies on 12 and 13, pulling to within one stroke of Cooper. A small blip occurred on 15, when Manero hit his tee shot in a greenside bunker and made bogey, his only one of the round. A birdie putt of 10 feet on 16 quickly righted the ship. Meanwhile, Cooper went on to bogey holes 14, 15, and 18 for a back nine score of 38 and final round score of 73.

On the closing holes, Manero’s thoughts were wandering. He was chatting away and reminding Sarazen how he had finished second to Cooper at the St. Paul Open a few years back. “Gene told me to cut out the ancient history and play the hole I was on. Sarazen is the golf businessman, all right, and that advice of his...kept me right on my knitting,” Manero remarked after the round. Manero came to 18 needing no worse than a bogey to win. There was a problem, however. Play had slowed and there were two groups on the 18th tee still. Manero was jittery; he went into the woods and paced. Sarazen tried to keep his tense friend calm. “Gee, Gene, they tell me I have a five left to win. What must I do?” Manero asked Sarazen. After what must have seemed like an interminable wait, Manero striped his drive down the middle on the 465-yard par 4. He and Sarazen walked down the fairway side by side. “Just keep on playing golf,” Sarazen encouraged

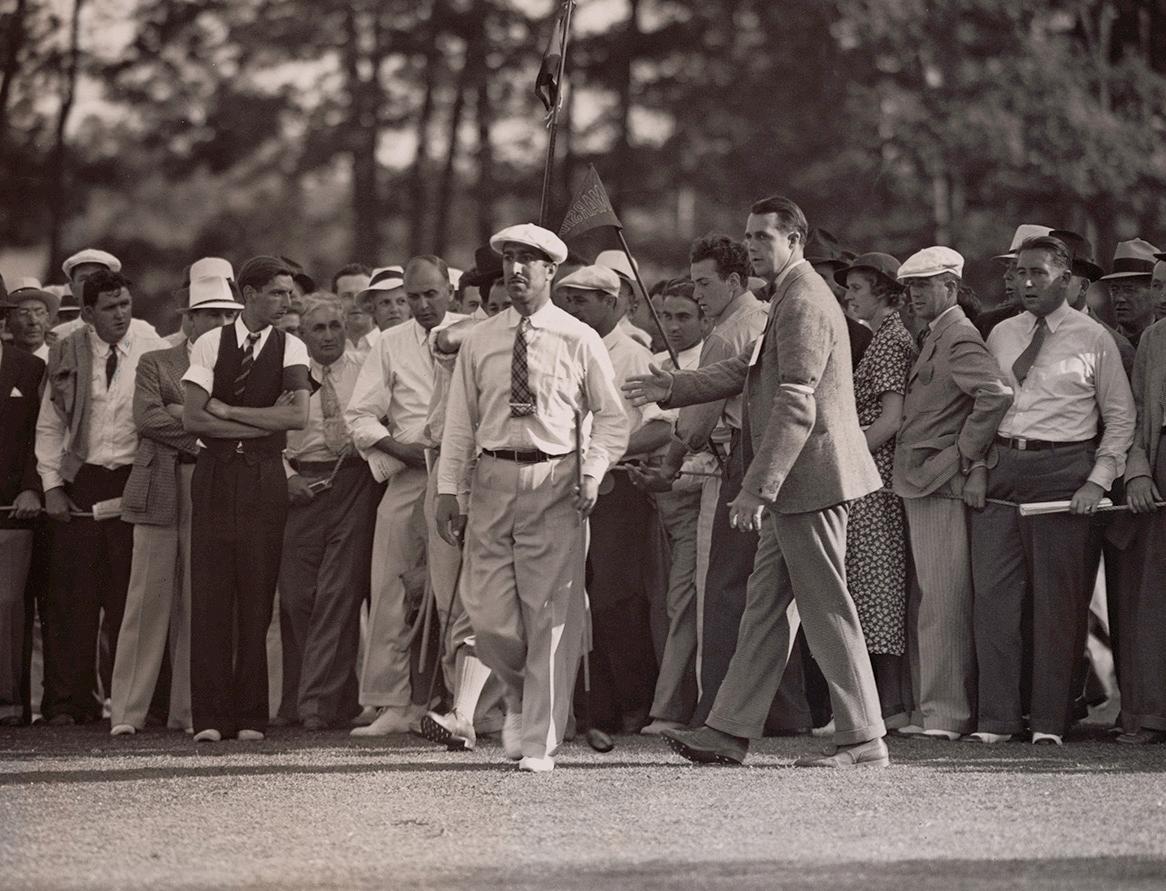

his friend. In the words of New York Times writer Lincoln Werden, “And then, with some 12,000 or 15,000 spectators forming an oval that extended from behind him [Manero] to the back edge of the green almost 200 yards away, the man who will be known as champion for at least another year... hit a screaming iron shot that just managed to get over the bunker on the left-hand side of the fairway, and left his ball on the magic carpet 15 yards or so from the pin, but as safe as Gibraltar, unless he were to four-putt.”

Minutes later, Manero made a five-footer for par; Sarazen raced over to collect the ball from the hole before Manero was engulfed by spectators and swept off the green. His final round 67 (-5) set a new course record on Baltusrol’s Upper and his 282 total established a new U.S. Open scoring record, about 30 minutes after Lighthorse Cooper had done the same thing.

But wait, would Manero’s victory stand? At least one reporter had submitted to the USGA that Sarazen had provided advice to Manero during the final round, a violation of the Rules of Golf. It also was alleged that Sarazen had requested the pairing with Manero in order to keep his friend calm under the Open pressure. USGA officials spoke to both players and huddled in a closed-door meeting for about 30 minutes; in the end, they determined that any emotional support or encouragement that Sarazen had offered or Manero had elicited did not constitute advice.

The trophy was Manero’s!

At “Tony Manero Day” in Greensboro a few weeks later, Manero’s triumphal win was celebrated. O.B. Keeler, the famous golf writer from Atlanta who chronicled the career of Bobby Jones, was present in the crowd. He told the audience, “There is no sporting event in the books as grueling as a National Open. It takes a wonderful fighting heart, a great competitive spirit, the ability to stand the hard knocks. This is what Manero had and did at Baltusrol.”

Championships on the Upper Course

Kathy Baker outshines a star-studded field to win on the Upper Course.

ber her presence at events. She came to the LPGA Tour after a very successful amateur career, playing on the Curtis Cup and Women’s World Cup teams in 1982. She was very active in the LPGA Fellowship Group which met most weeks that we played. I also attended the Fellowship meetings regularly, and Kathy was a woman of great faith. She was often a small group leader. I remember Kathy being tall and very statuesque and she had the look of a model. She was very warm and friendly and had a great smile. Kathy was very competitive, but I do believe that through her career, her faith was her top priority. Her hard work and success were a way for her to show her faith and shine through that. I believe Baltusrol has a wonderful U.S. Women’s Open Champion representative in Kathy Baker.”

Baker later married and changed her name to Kathy Baker Guadagnino. She played professionally until 1999. During her career, she had one other win on the LPGA Tour. As a playing professional, she juggled competitive golf with raising three children; two daughters and one son.

“I discovered I was pregnant with my first child, Nikki, while in Japan for a tournament and could not confirm the pregnancy until I returned to America,” Baker remembered. “While on the Tour, I used the daycare for the players and sometimes would bring a nanny with me, especially by the time I had my second daughter, Megan. Megan did not travel as well as Nikki. I would sometimes travel for a week with one daughter, and then my husband would come out the second week with the other one. Once I had my third child, Joe, it became a little more challenging to juggle golf and touring with children. Golf is such a mental game. My priorities at that point then started to shift.”

She currently lives in Florida with her husband and enjoys crafts and reading. Her victory at Baltusrol remains an iconic chapter in the championship legacy of the Upper Course.

Championships on the Upper Course

By Alex Cohen

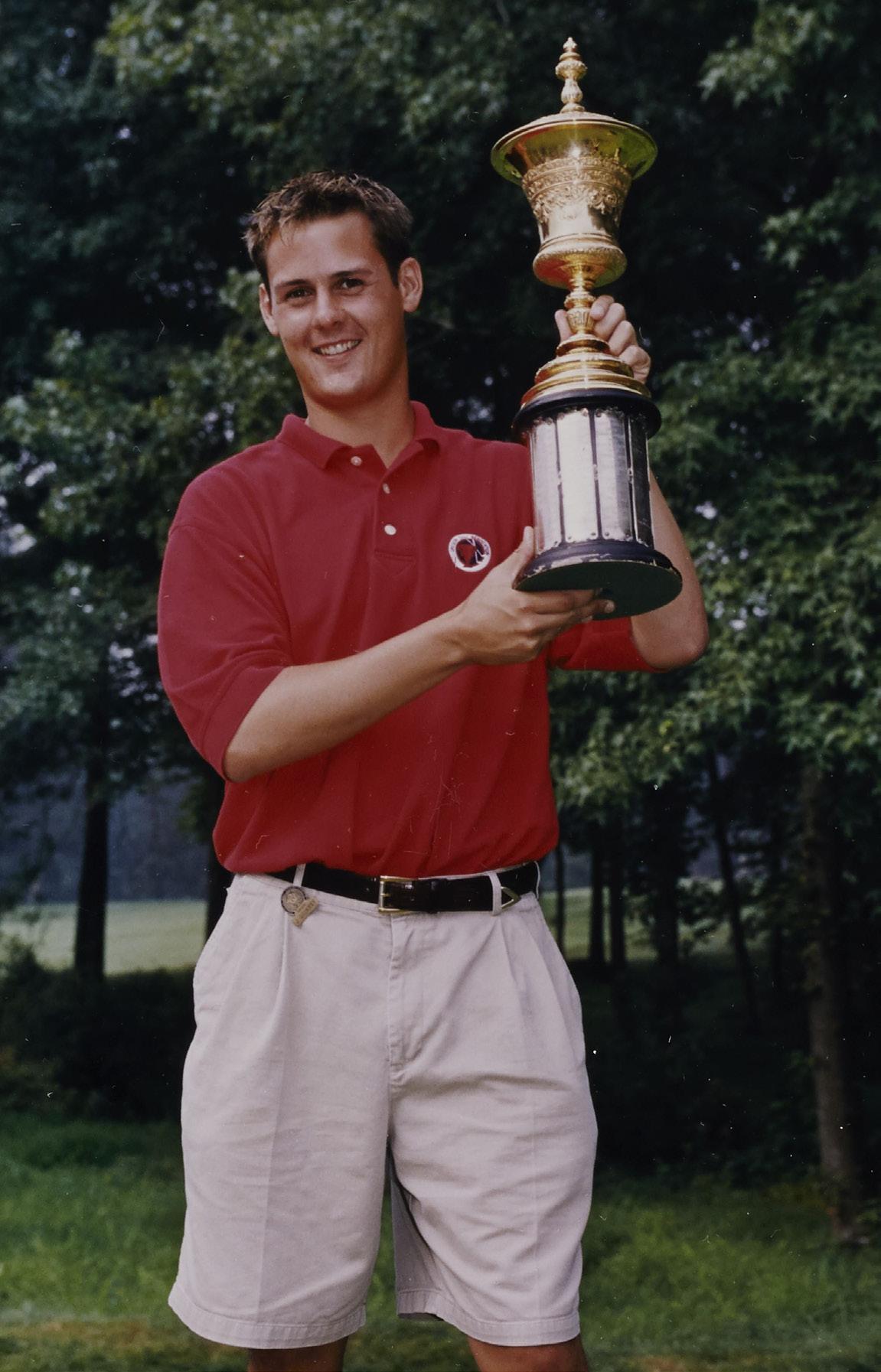

he 100th playing of the National Amateur Championship was another historic one. The qualifying rounds were contested over both the Lower and Upper courses, with the match play rounds on the Upper. Televised in 41 countries, the golfing world again focused its gaze on the famed Upper Course at Baltusrol.

The field included several future PGA Tour winners, but it was Oregon native Jeff Quinney and James Driscoll of Massachusetts who successfully navigated the match play bracket. Quinney’s run featured a come-from-behind trademark and included wins over 2009 U.S. Open winner Lucas Glover, as well as multiple Tour winners Ben Curtis and Hunter Mahan. Driscoll, a three-time All-American at the University of Virginia, never trailed beyond the ninth hole in any of his five matches prior to the final. His tightest victory came in the semifinals when he outlasted future PGA Player of the Year Luke Donald 2 and 1.

The final round between Quinney and Driscoll was another historic battle at Baltusrol. Quinney, a senior at Arizona State University, took an early lead in the morning round and was 2 up after 18 holes. A pair of bogeys from Driscoll gave Quinney a 4-up lead through 20 holes, and as the competitors approached the tee on No. 16 Upper, Quinney was 3 up with three holes to play.

In need of a miracle, Driscoll staged an amazing comeback that rivaled Tiger Woods’ legendary come-from-behind win over Steve Scott at the 1996 Amateur. Driscoll won holes 16 and 17 with birdies and sank a clutch par putt on 18 to send the match to extra holes. Both players parred the next two holes before play was

halted due to an impending thunderstorm.

That night, Quinney spent much of the night in his hotel room rolling out of bed and thinking about the par 3 that would greet him in the morning. He also thought about every stroke and hole that had taken place that day on the Upper Course. Quinney later remarked that he “wouldn’t have been able to forgive myself if I hadn’t pulled it out.”

The next morning, on the 39th hole of the match, Quinney sank a 20-foot downhill speedy putt on the third hole of the Upper to become the 100th Amateur Champion. The 39-hole match tied the longest final in U.S. Amateur history with the 1950 championship.

Quinney would go on to represent the United States at the 2001 Walker Cup before turning professional later that year. He earned three professional victories in his career. Driscoll also turned professional in 2001 and notched a pair of victories on the Nationwide Tour.

The 2000 U.S. Amateur was a tremendous showcase for the Dual Courses at Baltusrol and further cemented the Upper Course as a premier venue for major championship golf.

Championships on the Upper Course

By John Kimball

s a founding member of the Metropolitan Golf Association, Baltusrol has served as the site of several MGA major championships including the Met Amateur and the Met Open. Since 2002, Baltusrol has also played host to the Carter Cup, the MGA’s premier junior stroke play championship. The event honors Michael P. Carter, an accomplished junior player and standout member of the Delbarton School golf team. Carter was a junior club champion at Baltusrol and was a promising player on the Penn State University golf team when he tragically died in a car accident in 2002.

final score of 11-under-par was a new Carter Cup scoring record.

The Carter Cup is for amateurs who are 18 years of age or younger and who have not yet matriculated at college. The field contains the region’s top rising stars, who earn entry into the event based on their performance in notable Met area competitions. The tournament is highly competitive and capturing the cup is a coveted achievement.

The 36-hole event is played over both the Upper and Lower Courses in the same day. In its history, the Carter Cup has produced an impressive list of champions, including Cameron Young (2011), Cameron Wilson (2009) and Morgan Hoffmann (2005).

Barnes Blake became the first Baltusrol junior member to win the Cup, doing so in 2023 in record-setting fashion. Blake posted an outstanding two-round score of 133, clearing the field of 46 players by eight strokes. Blake followed up a morning 69 on the Upper with a course record-tying 64 on the Lower, and his

Mary Lou Carter, Michael’s mother and an active Baltusrol member, has stated that, “The Carter family is grateful to Baltusrol for supporting the Carter Cup since its inception. Mike came up through the Junior Golf program at Baltusrol and loved playing these courses. It has been truly gratifying to see the Carter Cup become a premier event for the best young golfers in the New York Metropolitan area.”

The cup itself has an interesting history. It was made by Tiffany, probably in the 1930s. The cup is made of sterling silver and originally was a gift given to an executive for his 35 years working for a railroad. It is believed the original recipient’s name started with a “C” and the trophy was reengraved to become the Carter Cup.

With the Upper Course closed for its restoration, the 2024 Carter Cup was played at Winged Foot Golf Club, where Michael Carter was also a junior club champion. The Cup returns to Baltusrol in 2025 and will again be played on the Upper and Lower Courses. For the first time in 2025, a girls’ division has been added to the event.