22 minute read

Speak of the Devils: Creative Faith in a Time of Pandemic

Cynthia L. Rigby

Only creative faith can resist the onslaught of destructive faith. Only the concern with what is truly ultimate can stand against idolatrous concerns. ––Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith1

Advertisement

Always use the proper name for things. Fear of a name increases fear of a thing itself. ––Dumbledore, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone2

“There’s got to be a reason,” replied my colleague and next-door neighbor, David Johnson, after I told him we had named our new kitten “Neville.” And he was right—there was. We had named him after Neville Longbottom from the Harry Potter series, the kid who plunges right into everything,

Cynthia Rigby is The W.C. Brown Professor of Theology at Austin Seminary. Her latest book is Holding Faith: A Practical Introduction to Christian Faith. She is a general editor of the nine-volume lectionary commentary series, Connections (Westminster John Knox). Current projects include a book on Christian feminist theology and one tentatively titled, Splashing in Grace: A Theology of Play.

despite his awkwardness and fear; the kid who never outgrows his dorkiness but winds up standing up to the demonic Lord Voldemort nonetheless. If I recall correctly, we chose the name just after we brought Neville home, set down his cage, and opened the door. To our surprise, Neville, a stray rescued from a friend’s car engine, didn’t hesitate. He walked straight out and plodded across our living room, his ears way too big for his head, looking around as though to say: “So this is my life, eh? Well, I’m gonna do what I can.”

This essay is about doing what we can to confront the devils at work in our world today, about living creatively in relation to the God who does not want us to aim to be revolutionaries, but to strive to be faithful. It suggests that what this means for our day-to-day lives is that we keep bumbling our way forward, eager to join in God’s work in the world—even when we are afraid, even when we have doubts, even when we go unnoticed—because we know we participate with others in something far greater than any isolated effort, in something that will endure, in the real reality of God which will one day untwist the oppressive distortions crafted by the devils of this world.3

This essay also attempts to articulate a critical proviso to the preceding sentences. We bumblers called “Christians” may gain the courage to push forward despite ourselves, believing that (as Martin Luther put it): “the right [one],” Jesus Christ, “is on our side.”4 But this is a very different dynamic than if we are certain we are right because we confess God is with us. When our faithfully bumbling forward despite fears and uncertainties is replaced by a self-righteous march of certainty, it is we ourselves—we personally, we the church, the institution, the nation—who might need to be exorcised.

It is on one level understandable that people of faith would rather march than bumble. After all, who doesn’t want to be seen as winsome, decisive, effective, heroic? Newsstands, bookstores, and newsfeeds are full of advice for how we can gain self-confidence and thereby influence and success. But confidence founded in certainty that we are right—rather than in the God who promises somehow to work our faithful actions together for good—quickly becomes idolatrous, even demonic. A prime and multiplying example of this phenomenon, noted by scholars from Reinhold Niebuhr to James Cone to Catherine Keller, is the extreme nationalisms that have been propagated in the western world over the last century and a half. When nations and national leaders connect without pause their conviction that “God is with us” to “therefore we are surely in the right”—especially when the claims being made are vague and unsupported—distortion and destruction follow.5

This phenomenon is sobering, highlighting again the importance of the question, How do we bumble forward to do what we can, confident that we are “friends of Jesus” (John 15:15) who know “the mystery of God’s will” (Eph. 1:9), without feeding the demons of self-righteous certainty, demons obsessed with gaining supremacy and idolatrously trying to take the place of the sovereign God? How do we make sure our faith is creative and not destructive, neither submitting to these demons nor merging ourselves with them in order to gain the power we want?

We need to develop a demon-handling skill set. Step one, I suggest, might be to

discern and name the demons that are threatening to destroy us or trying to recruit us. Step two would be to move forward despite our fear, determined to do what we can to participate creatively in God’s shaping of the future. Step three would be to keep checking up on ourselves and our siblings in the faith, repenting of ways we are complicit in feeding the demonic and resubmitting ourselves to being undone and remade by the God who will not be contained by even the most liberating human agenda.

Step One: Naming the Demons

When I say “devil,” “demon,” or “principalities and powers” (Eph. 6:12), I am not picturing substantive creatures.6 I am, however, drawing from classical ways of thinking that convey valuable truth about why it is so hard to be and to do what we are called to be and to do. The basic storyline is this: Satan and the demons were created by God as part of the good creation. And (like human creatures) they fell, turning away from what they were created to be and toward that which is not true or beautiful or willed by God, turning toward that which (according to Augustine) is the absence of good, toward evil. Ever since then, they have been driven to pull us away from our created (good) and redeemed (forgiven) identity, toward the evil that is not really real insofar as it was not made substantively by God and is not what finally defines us. But as liberation theologians James Cone and James Evans have noted, to be twisted in the wrong direction, away from God’s creative and redemptive purposes, has a devastating, substantive impact.7

What is important is not whether or not we believe demons have substance, but that we understand them as important ways of naming the substantive threat of destruction to our lives and well-being, and to the life and well-being of the world. With regard to the power of forces twisting us away from God’s creative and redemptive purposes, the traditional Christian storyline creates spaces for creative reflection. The threat is that we will never live into what Paul Tillich calls “our ultimate concern”; that we will never know what it is to participate so fully in that which is holy that we are utterly free to be the creative creatures God created us to be. If we resist who we are as finite, turning from mutual relation to others by entering into demonic systems in order to gain power and influence, our creaturely creativity—stagnated by lack of freedom—will dissipate. We might survive by destroying others, but we will only be misers. If we are on the other side of the dynamic and are being sucked dry by the demonic, on the other hand, Cone insists that we fight back. “If we are created for God,” Cone insists, “then any other allegiance is a denial of freedom, and we must struggle against those who attempt to enslave us.”8

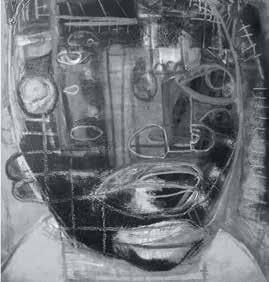

Theologians are not alone in the concern that the demonic meddles with human creativity, vocation, and fulfillment and therefore must be disarmed. Strategies are offered by therapists, doctors, yoga instructors, and motivational speakers. Consider Stephen Pressfield’s book, The War of Art, which argues that the demon he calls “Resistance” leads to the destruction of life by impeding us from “doing our work” of creating.9 In a similar vein, Lynda Barry advocates “drawing your demons”

as a way of naming them and gaining the freedom to create10

Before demons can be named and disarmed they must be correctly identified. In the history of spirituality, demons are referenced as being all around us but are difficult to recognize. “Even Satan comes as an angel of light,” the Apostle Paul reminds us, so it should not come as a surprise that “false apostles . . .disguise” themselves as “ministers of righteousness.”11 Pressfield points out that even something as angelic-sounding as “self-care” can feed the demon of Resistance if it keeps us from doing our creative work.12

Theologians offer various guidelines for differentiating between that which is of God and that which is not. John Wesley, for example, in mid-18th-century England exhorts Christians not to confuse the Holy Spirt with the human spirit, advising them to look for the “fruits of the Spirit”—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control—as evidence of true religion.13 Swiss theologian Karl Barth, critiquing western capitalism in the mid-20th century, argues that “the command of God is self-evidently and in all circumstances a call for counter-movements on behalf of humanity and against its denial in any form.14 William Stringfellow, lawyer and lay theologian in the 1960s United States, suggests we test the institutions we are involved in with three criteria that can help us assess whether or not they are veering toward the demonic: 1). “the denial of truth;” 2). the use of “doublespeak” and “overtalk” (terms born from Orwell’s famous novel, 1984, where telescreens blare in every home with distorted messages such as “war is peace,“ “freedom is slavery,” and “ignorance is strength”); and 3) “secrecy and boasts of expertise” (generally on the part of leaders or institutions asking followers to trust their superiors unquestioningly).15 And James Cone, black liberation theologian of the early 21st century, insists that Jesus Christ is the final criterion for discerning that which is from God and that which is not. “Jesus Christ is the ground of human liberation,” he notes, therefore, “any statement that divorces salvation from liberation . . . must be rejected”16

While these and other criteria have repeatedly proven helpful to Christians who want to name and challenge the demonic, Catherine Keller suggests that this era marked by the pandemic might offer a unique opportunity insofar as it offers a clearer view of usually more camouflaged demons. We live, in fact, in a time of “pandemic pandemonium,” says Keller, playing seriously with both the alliteration and the etymology of these two words: (1) pan-demic (meaning “all people;” as in all of us are affected by COVID-19) and (2) pan-demonium (meaning “all those demons;” as in the pandemic isn’t the only thing we are dealing with by a long shot!). Keller points out that the word “pandemonium” was created by John Milton and introduced in Paradise Lost. It is the name he gave to the capital of hell,17 Keller explains, a city created not by Satan, but by the biblically named god, Mammon. Mammon created that “elegant” city with all the treasures of the world (3).

Keller suggests the coronavirus is forcing us to see demons that we often overlook. Our deep-seated systemic racism is exposed, for example, by the fact that while people who are African American make up only thirteen percent of the population, they account for a third of coronavirus deaths (2). The demon Keller calls

“the sickness in our food supply” is exposed by our pre-existing conditions, caused by inflammation in our bodies due to what we eat (2). And the demon of “environmental demise” is evident in the still-unfinished story of how the coronavirus came to be, a story that surely includes humans pushing other animals out of their natural habitats (3). These are three of many examples.18 “In this moment, these pan-demons dance garishly into view through the pandemic interruption of normalcy,” Keller says, “and so they get demoralised for a moment. And they seem just too much. Too many. Too many feverish issues to address all at once” (4). It is no wonder we want to get back to “normal,” to re-coat Pandemonium with its glitter so we won’t have to see—and contend with—the insidiousness of what is always there.19

If Keller is right, this moment assigns us a great responsibility. The demons are out and we can see them clearly. We need to act to point them out to others before we “return to normal” and they once again become less visible. As we struggle to live out our faith in the midst of this crumbling Pandemonium, how may we keep courageously bumbling forward, defying the demonic by rejecting self-righteousness and refusing to hope either for a return to that glittering normal or to survive whatever “new normal” comes upon us? How might we eschew such destructive faith and do what we can to step out and to contribute creatively to the shape of our future?

Step Two: Moving Forward Creatively

The destructive work of the demonic, as we have said, is to keep us from living before God as the creative creatures we are. On an individual level, the demons related to this can be named and countered in a variety of creative ways: through good parenting, friendships, worship practices, prayer, therapy, discipline, meditation, and other strategies. But how do we move forward faithfully in relation to the demonic as it has invaded our lives at an institutional level, a national level, even a global level? What can we do to stop the destructive, idolatrous powers that keep us thinking and operating as though some people are superior to others because they are white, rich, male, straight, American, or members of some other privileged class? Walter Wink believes that, in relation to systemic distortion, our “spiritual task is to unmask this idolatry and recall the Powers to their created purposes in the world.”20 We might recall, as an example of this, that Luther addressed his prophetic ninety-five theses to infidelities of the Roman Catholic Church (which soon thereafter strove to reform itself in the so-called Counter-Reformation), or that Calvin prefaced his Institutes of the Christian Religion with a subtly prophetic appeal to King Francis I. This task, Wink insists, cannot be done alone. It requires the efforts of the entire ekklesia. Moreover, he adds, “The church must perform this task despite its being as fallen and idolatrous as any other institution in society” (369).

Wink is right about the need to work in community. But I would suggest that if the church is creatively to challenge the destructive power of the demonic, it needs to do more than act despite its fallenness and idolatry. Might there not be a way to factor our own complicity with and experiences of the demonic (as individual

people of faith and as contributing members of “fallen and idolatrous” institutions) into the content, actions, and timbre of our faith itself? In other words, is it possible to engage the “spiritual task” to which we are called in a more whole, robust, and self-reflective way than by simply acknowledging we are “wicked rascals” and moving forward nevertheless?21

Paul Tillich suggests an approach to faith that folds aspects of our experiences of the demonic into the life of faith itself in ways that can actually strengthen our capacity to move forward to confront life-destroying powers. Tracing this via the example of Neville confronting Voldemort, notice that Neville doesn’t start his final speech with words of triumph, but by acknowledging the finality and emptiness of death. “It doesn’t matter that Harry’s dead,” he says, “People die all the time. Friends. Family.” J.K. Rowling puts these words in the mouth of a character who knows what he is talking about, for Neville’s parents have been so gruesomely tortured that they can no longer recognize him. While Harry’s murdered parents are celebrated, Neville’s are only pitied. From the vantage point of a faith certain of triumph, these first words of Neville’s speech might be considered too negative, faithless, even destructive. But from the vantage point of Tillich’s paradigm, Neville’s faith is creative because it neither submits to the demonic nor denies its power, but factors it into his courageous and vulnerable response.

The same can be said of the psalmist who demands that God wake up (Ps. 44:23); of Mary when she holds Jesus accountable for Lazarus’s death (Jn.11:21); and of Jesus when he calls God out for abandoning him on the cross (Mk. 15:24). Tillich advocates that we risk embracing the dangerous doubts, questions, and uncertainties that come right up against rejecting the God of power and justice because he believes doubts, questions, and uncertainties keep us open to experiencing the “God above God”—the God who does not conform even to our most progressive agendas or ideologies, the God who is, as Tillich likes to put it, “our ultimate concern.” Tillich concludes, “The courage to be is rooted in the God who appears when God has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt.”22

Allow me to back up and describe Tillich’s paradigm in another way before trying to bring the “so what” of all this home. This time I will begin with Tillich’s conception of God and move to describing faith rather than the other way around.

God, for Tillich, defines God’s own self. Who God really is lies beyond even our very best definition. God is holy, but only God decides what that means. We tend to see and define the demonic as the opposite of holy. But Tillich insists (as do Barth and Cone) that God won’t be confined by some definition of God that makes sense to us. Tillich looks at the world and at our lives and thinks things are messier than such simple “opposites” (or binaries) will allow. Writing as a Westerner in the heart of the Cold War, he notices that people tend to think they must choose to understand God in one of two ways. In the first, God is the One whose holiness destroys us, who scoffs at the ideals of freedom and creativity, who demands unquestioning submission and obedience. In the second, God is the One whose holiness corrects the demonic God of way #1, demanding retribution for injustice and proffering freedom and creative opportunities for all.

The second God is the clear choice of the 20th-century Western world. But here’s where the problem comes in, according to Tillich: this understanding of God—this God who counters the idolatrous, tyrannical God of way #1—“replaces holiness with justice and truth.”23 What we have done in adopting such a God, however inadvertently, is create another god we carry with us into wars, into political campaigns; the “God” who is on our side, the “God” who wins, the “God” who makes our nations great and will help us return to normal. Faith that follows this god rather than the God above God will wind up destroying creativity in the name of freedom, according to Tillich, because it is closed off from the possibility of holy destruction that leads to the creation of new being. In contrast to this, the creative faith of true religion resists reducing God to either (or any) option, refusing to march in lockstep, embracing experiences of the abyss, and bearing courageously the danger that it will itself be transformed by the subject of its ultimate concern.

Step Three: Staying Open to Holy Destruction

How, in the midst of the current pandemonium, might we develop and maintain a creative and open faith that knows how to walk humbly with the God who calls us to do justice and to love kindness?24 What does it look like, in Tillich’s terms, to stay open to dynamic interaction with the God above God; to submit to the one who may call us to let go of our well-formulated ideologies for the sake of contributing to a new normal that we cannot yet imagine? What does it look like, in Cone’s terms, to live as those who remember that our experiences “are not the Truth itself”; even when they are a “source of the Truth”; to recognize that the Truth of Jesus Christ, is “so high we can’t get over it,” “so low we can’t get under it,” and “so wide we cannot get around it”?25

There are several answers to this, explicit or implied, weaving their way through this essay. First, faith that is open to holy destruction engages constantly in the hard work of self-reflection. We should humbly and constantly apply to ourselves and our own actions the criteria for discerning the demonic that have been passed on to us by wise members of our communities of faith. Corresponding to this, we should ask others to hold us accountable for staying creative—refusing either to be disempowered by those who have succumbed to the devils or to being lured into that ugly work ourselves.

Second, creative faith that is open to holy destruction must guard against being reduced to a static and rigid ideology. As Cone reminds us, sources of truth should not be leveraged as truth itself; even when we are right, we have not exhausted what is true, good, and beautiful. To the degree that we know this, we are prepared to join together freely with a diversity of other creaturely creators, contributing essentially to the creative work of the God that is always greater than any of us—and even all of us altogether—can ask or imagine. To resist codifying the desires of God (or to call out the principalities and powers that are doing this instead of hoping they will just go away) takes constant attention and self-recalibration. It requires from us the spiritual discipline of daily re-submitting in love to being living sacrifices, bumbling our way forward to be transformed by the living Word of the God

who is above God.26

Finally, creative faith that is open to the melting and the molding of the Holy Spirit cries out with the questions and uncertainties that rise from the disappointments, agonies, and betrayals we have experienced in relationship to the holy. As Tillich notes, we don’t spend a lot of time and energy being uncertain about things we don’t care about. We wrestle with uncertainty only in relation to that which is of ultimate concern to us; only in relation to that in which we have put our trust. Jesus’s agonizing cry of “Why?” then, is not simply an expression of doubt that is understandable and forgivable, given the circumstances. Jesus’s “Why?—and ours—is essential to the work of transformation insofar as it manifests our ongoing struggle to hold on to what matters most in the midst of the pandemonium that surrounds us. To ask “Why?” is to refuse to submit passively to God’s “secret will” (Calvin).27 It is to insist on remembering and interpreting what is happening in light of the history of our relationship to God.28 It is to be poised to condemn the destructive power of the demonic even as we keep an eye out for what the God above God might be up to, even if we don’t like it. Finally, it is the way to join with all creation in the “groaning for redemption” that keeps us bumbling forward in hope, watching and working for the day when all will be “set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God.”29 v

NOTES

1. Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith (New York: Harper & Row, 1957), 30. 2. J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (New York: Scholastic, 1997), 298. 3. Drawing here from the imagery in v. 1 of “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”: “And though the world with devils filled should threaten to undo us, we will not fear for God has willed, [God’s] truth to triumph through us” (https://www.hymnsite.com/lyrics/umh110.sht; last accessed 8.22.20). 4. Drawing here from the imagery in v. 2 of “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.” 5. For a recent example of the idolatrous conflation of nationalism and God, see Vice President Pence’s speech at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2020/08/27/pence-bible-rncjesus-flag/ (accessed 9.21.20). Thanks to Kevin Ireland for providing this example. 6. I developed my understanding of what constitutes the demonic in “Evil and the Principalities: Disarming the Demonic,” in Life Amid the Principalities, eds. Michael Root and James J. Buckley (Eugene: Cascade, 2016), 51-67. 7. See James Cone, The God of the Oppressed (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1997), 160, and James Evans, We Have Been Believers: An African-American Systematic Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992), 8. 8. Cone, 145. 9. Stephen Pressfield, The War of Art (New York: Black Irish Entertainment, 2012), passim. 10. Lynda Barry, One! Hundred! Demons! (Drawn and Quarterly), 2017. 11. II Cor. 11:13–15. 12. Pressfield, 112. 13. Galatians 5:22; John Wesley, “The Witness of the Spirit I,” In John Wesley’s Sermons: An Anthology. Eds. Albert Outler and Heitzenrater (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999). 14. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, eds. Geoffrey Bromiley and T.F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1956–1976, 12 vols), III/4, 544. 15. William Stringfellow, Essential Writings (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2013). 16. Cone, 141. 17. Catherine Keller, “Pandemic Pandemonium,” At https://www.abc.net.au/religion/ pandemic-pandemonium-catherine-keller/12281594. Other references to this essay will be indicated parenthetically.

18. If you are using this article in a group study, it might be constructive to pause and make a list of the demons being exposed in our times. 19. For more on how we should respond to the cultural yearning to get back to normal, see the end of Keller’s article and also my article titled “Eccentric Hope” (Perspectives, Vancouver School of Theology, Summer 2020) at https://vst.edu/perspectives/eccentric-hope/. 20. Walter Wink, The Powers that Be: Theology for a New Millennium (New York: Doubleday, 1999). 21. I am drawing, here, from the language of Karl Barth in Church Dogmatics IV/2 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark), 666. 22. Paul Tillich, The Courage to Be (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). 23. Tillich, Dynamics, 17. 24. Micah 6:8. 25. Cone, 33. 26. Romans 12:1-2. 27. For more on my critique of Calvin, see “Providence and Play” in Insights (126:2; Spring 2011), 10–18. 28. Consider how often the lament psalmists rehearse the history of their relationship with God (e.g., see Psalm 44). 29. Romans 8:21.

Questions for Discussion by Professor Rigby