4 minute read

HONORING AMERICA’S OVERSEAS WAR DEAD

Ryan Blum ’16 | TUNISIA

The North Africa American Cemetery, situated on the Tunisian coastline, honors US soldiers killed in combat in the region during the Second World War. Here, Ryan Blum ’16, the cemetery’s superintendent, discusses the importance of giving meaning to their memory.

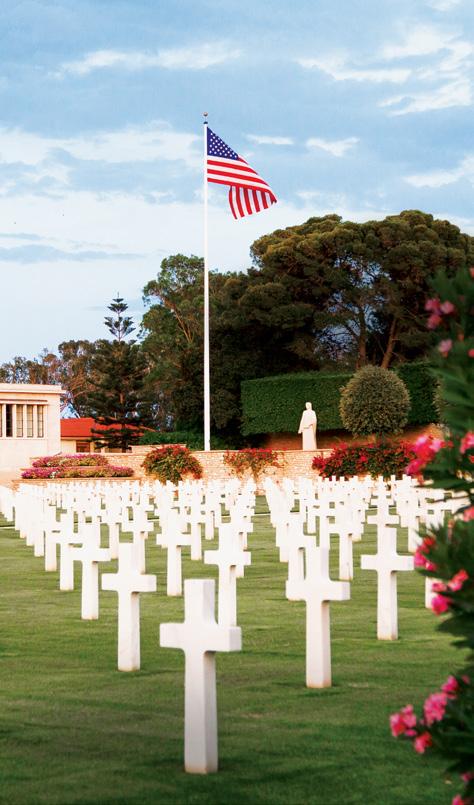

When most people think of Carthage, they think of Hannibal, his elephants and the 100-year war with Rome that left the city in ruins; when I think of Carthage, I picture the nearly 3,000 bone-white Latin crosses and Stars of David symmetrically set among immaculately manicured gardens and hand-raked gravel pathways. Welcome to the North Africa American Cemetery, one of 26 American military cemeteries and memorials located overseas and the only one located on the African continent. Each headstone bears the name of a young man or woman who lost his or her life in one of the most overlooked campaigns of the Second World War.

Ryan Blum, Superintendent of the North Africa American Cemetery

As the cemetery’s superintendent, it’s my job to try to teach visitors the importance of what took place here. I never imagined five years ago, when I was just starting my AUP experience, that my life would eventually lead me to direct an American military cemetery on the North African coastline. Cemeteries, after all, are not generally where people think or want to work, and, to be perfectly honest, not too long ago I probably would have struggled to locate Tunisia on an unmarked map. After two years, however, it’s difficult to imagine myself wanting to do anything else. These cemeteries are so much more than dignified burial grounds: they stand as reminders to the world of the sacrifice of American youth. The American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) – the tiny federal agency tasked with designing, constructing and preserving these cemeteries – has ensured the sites remain the most beautiful and meticulously maintained shrines of their nature in the world.

The North Africa American Cemetery, located in the present town of Carthage about ten miles from Tunis, is no exception. The North African campaign turned the tide against the Axis forces that had swept nearly all of Europe. It was in the hills, passes and valleys of central and northern Tunisia that America first gained her confidence. This confidence would lead her to eventually storm the beaches in Italy and later in Normandy, but, more importantly, it signaled the dawn of the American century: never before had the United States acted as a leader and world power in this way.

Three quarters of a century have passed since those buried here lost their lives, but those lives are no less sacred than the lives lost today. The ABMC’s mission, summed up in the words of General of the Armies John “Blackjack” Pershing, who was also the commission’s first Chairman, is to ensure that “time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” To combat this ever-present threat, the cemetery welcomes thousands of visitors from around the world, hosts annual ceremonies and invites numerous distinguished guests to come pay their respects. Most important, however, are the organized school visits; these hallowed grounds must serve a new purpose, which is to educate the next generation about the sacrifices it took to make the world safe for democracy. Democracy is the idea that all men are created equal and have the right to participate in their government’s decision-making. It’s an idea that’s more fragile than we would like to admit; we need places like this cemetery to ensure that idea is upheld and that we never forget what’s at stake.

The North Africa American Cemetery in Carthage,Tunisia

It’s difficult to fully describe how powerful walking the grounds of one of America’s overseas cemeteries can be. Unlike the national veterans’ cemeteries, or Arlington Cemetery, these sites only contain the remains of those who lost their lives overseas, primarily during the First and Second World War. There are no veterans buried at my cemetery, no family members; only those who lost their lives here are allowed to be buried here. This restriction forces visitors to confront the reality of war; the true cost, evident when gazing upon row after row of headstones, brings many to tears. Communicating that cost is a vital task.

The need to create such places arose after the Great War, when the American government gave the families of the fallen a unique option to either repatriate their deceased loved ones to the United States or to inter them in a permanent military cemetery overseas. The majority of the families, understandably, took the decision to bring their loved ones back. However, nearly 40% of the American war dead remained permanently overseas at the request of their families. The percentages were similar after the Second World War.

Every day I reflect on what an extraordinary decision the families of those buried at my cemetery made, deciding that not only should their loved ones lie forever with their comrades-in-arms, but more importantly that they should serve as a perennial reminder to us, the living, of the sacrifice their families endured so that the ideals for which they lived and died would never be forgotten. As one next-of-kin wrote to the government, “We have given you our dead, now give them meaning.” I pray the weight of that responsibility and duty will never be lost on me.

I encourage all of you to visit at least one of the cemeteries in your lifetime. Truly look at each headstone and take the time to read the person’s name out loud. Try to imagine the future each person sacrificed for us. I promise you will be strengthened by the courage of the fallen, heartened by their valor and inspired by their memory. It will, more importantly, ensure that General Pershing’s words do not ring hollow and that, indeed, time has not dimmed the glory of their deeds.