3 minute read

Purim: The Most Dangerous Festival of the Jewish Calendar

Ittay Flescher

Purim is one of the most dangerous festivals in the Jewish calendar.

Advertisement

Centered around a revenge fantasy against the most hated enemy of the Jewish people, taken literally, the story of Megillat Esther has more intrigue, violence, and gore than a Quentin Tarantino film.

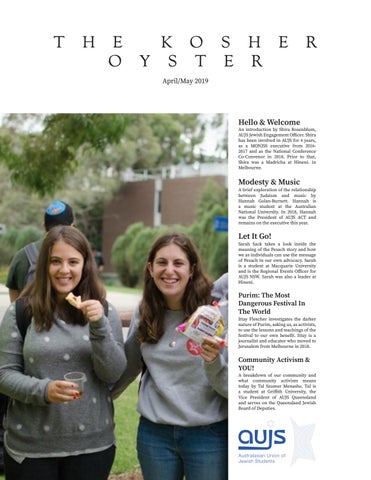

Thankfully, in their great wisdom, the Rabbis and the Jewish people today have turned Purim into a festival of joy, fancy dress, tasty foods and gifts to the needy.

Fringe extremist Rabbis in Israel view Arabs or Palestinians as the descendants of Amalek, but the majority view Amalak as an evil inclination within us all with which we should struggle to overcome. Imagining for a moment that this wasn’t the case, consider the following aspects of the Purim story.

In Megillat Esther, following Haman’s extermination decree against the Jews, King Achashverosh “permitted the Jews of every city to assemble and fight for their lives; if any people or province attacks them, they may destroy, massacre, and exterminate its armed force together with women and children, and plunder their possessions” (Esther 8:11-13).

The megillah explains that following this command for armed violence against an entire nation including women and children, “the rest of the Jews, those in the king’s provinces, likewise mustered and fought for their lives. They disposed of their enemies, killing seventy-five thousand of their foes; but they did not lay hands on the spoil. That was on the thirteenth day of the month of Adar; and they rested on the fourteenth day and made it a day of feasting and merrymaking.”( Esther 9:11-17).

At this point in the story, no Jew has been harmed, and 75,510 Amalekites are dead. Celebration ensues, to this very day.

For generations, anti-semites used this story to explain how awful Jews were as a people. In his infamous Antisemitic book of 1543, “On the Jews and their lies,” Martin Luther King wrote, “How much the Jews love the Book of Esther, which so well fits their bloodthirsty, vengeful, murderous greed and hope.”. Over time, various movements within Judaism began to question the Purim story for these reasons.

The famous 11th Century scholar Abraham Ibn Ezra, who was clearly uncomfortable with the violence, asked, “Why did Mordechai write that the Jews should kill their enemies? Would it not be enough for him and for them that they (the Jews) should escape?” Leading 19th-century British Reform scholar Claude Montefiore, in an editorial in London’s Jewish Chronicle in March 1888, went so far as to call for Purim’s abolition.

I remember once asking Rabbi David Hartman who was well known for his liberal Orthodox views, how he justified celebrating this festival. He explained that one needs to read the story as a projection, rather than history. Hartman believed that at the time the Megillah was written, the Jews didn’t have the power to vanquish their enemies with anywhere near the force and brutality depicted in the megillah.

Given their powerlessness, what they did was tell a story of their great might and fidelity to a God who fights on their behalf. The reading of the megillah each year then became a ritual of catharsis for Jews who over the centuries, had no political authority nor army, but for a day a year could see themselves as being the most powerful nation on earth.

Hartman also explained that one mustn’t forget what Haman is alleged to have done in the story. When Mordechai did not bow down to him, his rage did not extend just to Mordechai, but to the whole Jewish people.

Jews have always suffered from a generalisation of certain acts that individual Jews do, and to be labeled as misers, as cheats who will always lie to steal more money. “We who have suffered from the disease of generalization must not fall into the same pitfall, the same demonic urge to seek revenge on a whole people, because of the actions of singular individuals,” explained Rabbi Hartman.

As AUJS students on campus, the activist in you must choose each day how you respond to both the positive and negative generalisations directed towards your faith and the State of Israel. With different readings of the Purim story, one can find justifications for all sorts of response. My hope for those reading this now is that you will heed the words of Rabbi Hartman, to use this festival as a time to remind yourself of the importance of rejecting generalisations on both of the argument with which you agree and the one you oppose. That is truly where our power and strength resides, and it’s the most Jewish thing to do.