4 minute read

Grand Designs

from Aston in Touch 2017

by Aston Alumni

Birmingham has more miles of canal than Venice. That phrase will be familiar to any Brummie even though, like many memorable pieces of marketing, the truth of the statement is questionable (the Council website wisely hedges its bets with “Birmingham has 35 miles of canals, which is said to be more than Venice”). However, Birmingham has something else in common with Venice which is much more important - both are cities founded on trade. It all started in the last quarter of the 18th century when a group of amateur experimenters, tradesmen and artisans formed The Lunar Society. Foremost amongst them was the ambitious toymaker Matthew Boulton whose Soho Manufactory became internationally famous for producing plated metalware, buttons and coins. Boulton and his business partner James Watt (of Steam Engine fame) are often pressed into service as the figureheads of Birmingham’s industrial might, but there are numerous others contributors to scientific knowledge: James Brindley, who built the canals; William Withering, discoverer of the first heart medicine; Joseph Priestley, the man who ‘isolated’ oxygen and invented soda water.

These stories have been told, of course, and often airbrushed (we are rarely reminded that Priestley was driven out of Birmingham by rioters, angered by his support of the French Revolution, for example). Yet, as Andy Street acknowledges, even with founders of this stature, Birmingham has always been bad at shaping a narrative about itself. Street, who holds an Honorary Doctorate from Aston University, fought and won a nail-biting campaign to become the region’s first Mayor last April, and before that served as Chair of the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership. As the former Managing Director of John Lewis, he knows something about trade - and Birmingham: a city which he loves, despite its dislike of backward glances (the city motto, after all, is ‘Forward’).

Advertisement

“We probably reached our peak of relative industrial might in the 1960s,” he says (that ‘our’ is typical of his warmth towards the city). “At that time the Austin works at Longbridge employed over 60,000 people and there’s no question that the scale of industrial production here at the time was enormous but it gave a vulnerability to our economy.”

As he explains, by the 1970s the UK was engaged in a gradual process of deindustrialisation that hit Birmingham hard. Nevertheless, the city retained its characteristically upbeat attitude, as showcased in a 1960s promotional film voiced by Telly Savalas featuring a city bristling with concrete and cement. “You feel as if you’ve been projected into the 21st-century,” Savalas says at one point, speaking from a safe distance in his Los Angeles recording studio. The optimism, however, was real. “That’s how we portrayed ourselves to the world, but what actually happened was a challenging economic performance.” Street paints a grim picture of Birmingham’s employment figures, which declined from the early 1970s, and kept doing so, right through the 1990s to the early 2000s - a period when the rest of Britain enjoyed relative prosperity. The civic response, though, was suitably muscular. The canal at Brindleyplace was redeveloped and in its wake came Symphony Hall and the International Convention Centre. Street is evangelical about the power of retail to transform cities: “In 2003 we saw Selfridges and the rest of the new Bullring development open, and they played their part in the regeneration of the city but we were in a challenging position at the back end of what should have been a boom period, up to 2007.” It must have been no small frustration for Brummies to discover that, despite their best efforts, Londoners still associated their city with Spaghetti Junction, but in their cheerful way they embraced the clichés and did what came naturally: they put the traffic interchange on postcards and mugs and sold them to tourists.

That was then; this is now. Street is ebullient about the city’s prospects, talking of a Birmingham “Renaissance” which began with a £1 billion investment into New Street Station (now Grand Central Station) and the tram network, and is continuing with the new Paradise development.

Andy Street, West Midlands Mayor

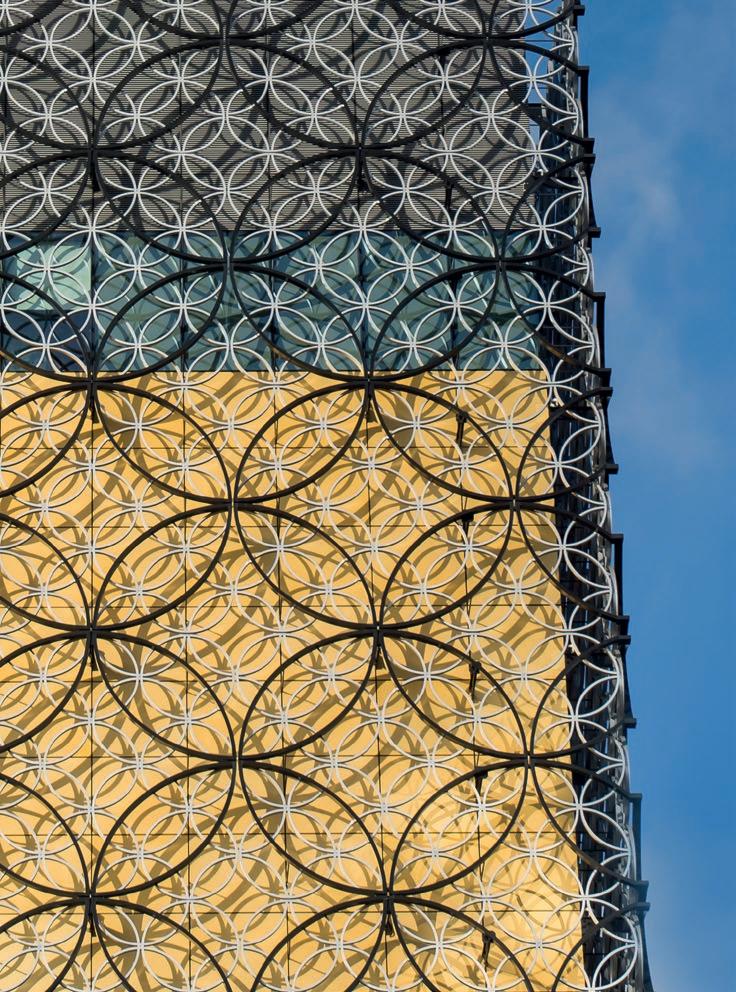

At the time of writing, there is a crater in the ground where the old Birmingham Central Library stood - an iconic Brutalist structure by the architect John Madin, first opened in 1974 and famously dismissed by Prince Charles, who thought it looked like “a place where books are incinerated, not kept”. Last year it was finally sacrificed to the Brummie gods - the diggers and concrete-crushers that are a permanent feature of modern urban life. To some it was a sad goodbye, but the long-view of history has much to teach us, not least that Birmingham also knocked down its Victorian municipal Library, featuring a splendid clerestoried reading room, to make way for Madin’s inverted ziggurat. The replacement for Madin’s structure - the Library of Birmingham - was opened in 2013: a gigantic metal wedding-cake of a building in a style known as Postmodern High-Tech. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose as the French say.

But what of the new Paradise development which is springing up from the ashes of the old Central Library? “You can decide whether it’s appropriately-named,” says Street dryly of the extensive building work, “but we believe that this is an enormous opportunity. First of all, HSBC are putting their retail headquarters here, right opposite Symphony Hall. This is an enormous coup for Birmingham. We are bringing the Midland Bank, founded in 1834, back to its original home.” He also mentions the Smithfield development, which is destined for the site that currently holds the Wholesale Markets. This, says Street, is “easily the biggest urban regeneration opportunity in any European city” and will hopefully become a major new public space for Birmingham. And then there’s HS2, with its terminal very close to Aston’s campus. “The simple fact is that Birmingham will be just 39 minutes from Euston. Critically, the whole lesson of history is that places that are close together will trade with one another. This is an enormous economic advantage for us because Curzon Street station will eventually be at the heart of a new high-speed network for the whole country.”

Like Venice, Birmingham is having its own Renaissance. But it’s newer, bigger and better - of course.