32 minute read

Research Corner

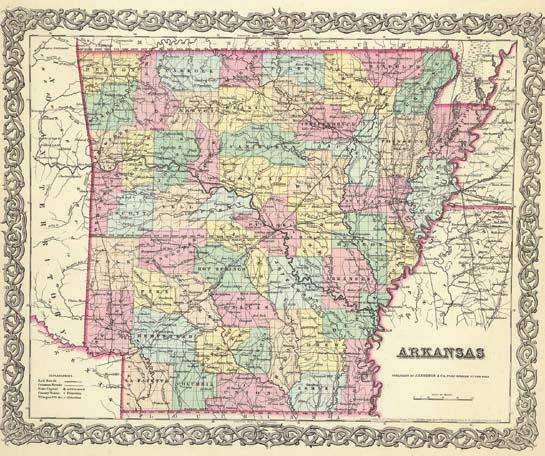

How many counties have dual county seats?

Are you sure about that?

By Mark Whitmore AAC Chief Legal Counsel & Jarrod Kinnaird AAC Law Clerk

Currently, 10 counties have split judicial districts. These counties are: Arkansas (founded in 1813), Carroll (1833), Mississippi (1833), Franklin (1837), Yell (1840), Prairie (1846), Sebastian (1851), Logan (1871), Clay (1873) and Craighead (1859). However, having split judicial districts does not mean a county will have dual county seats.

“It does not appear to be the case that a county that has two judicial districts will necessarily have two ‘county seats,’” according to Attorney General Opinion 117 (2006). The bulk of the citizens and Arkansans generally believe that there are 10 counties in Arkansas that have dual county seats. How many counties truly have dual county seats?

What are “county seats?”

County seats are considered “the principal site” for conducting county business, as well as the storage of certain records. County seats serve multiple purposes for a county in Arkansas. County seats are to be erected in each county, and where established should contain a courthouse and jail. Bond v. Kennedy, 212 S.W.2d 336, 337 (Ark. 1948). The county, circuit and other courts held for the county must sit there. Williams v. Reutzel, 60 Ark. 155, (1895).

How are county seats created?

County seats are created by a vote of the majority of the people. However, a temporary county seat can be created by law. The Arkansas Constitution, Article 13, Section 3, prescribes: “No county seat shall be established or changed without the consent of a majority of the qualified voters of the county to be affected by such change, nor until the place at which it is proposed to establish or change such county seat shall be fully designated: Provided, that in formation of new counties, the county seat may be located temporarily by provisions of law.”

This is also codified in Ark. Code Ann. § 14-14-302(a): “(a) Unless for the purpose of the temporary location of county seats in the formation of new counties, it shall be unlawful to establish or change any county seat in this state without the consent of a majority of the qualified voters of the county to be affected by the change; nor will a county seat be located until the place at which it is proposed to establish or change any county seat shall be fully designated….”

How is a county seat removed or eliminated?

A county seat is removed or eliminated in the same manner as it was created, by an election of the qualified electors voting in the county seeking to remove the county seat. An election for the removal of a county seat is an “election” within the general election laws and is governed thereby. Walsh v. Hampton, 132 S.W. 214, 216 (Ark. 1910).

See “COUNTY SEATS” on Page 26 >>>

Logan County Courthouse (Paris, 1873) Logan County Courthouse (Booneville, 1901)

The process for removal begins with a petition circulated by the qualified voters of the county. Whenever 15 percent of the legal voters of any county in this state shall join in a petition to the county court of the county for the change or removal of the county seat, the county court shall order an election to be held at the voting places in the county directing that the proposition of the petitioners for the change or removal shall be submitted to the qualified electors. Ark. Code Ann. § 14-14-303 (1987). The number of signatures required upon a petition for change of a county seat shall be computed upon the total vote cast for the Office of Governor at the preceding general election.

Act 166 of 1923 purported to authorize the removal of a county seat of Woodruff upon the vote of the electors of the county. The requirement for a county to establish a dual county seat or to remove a county seat is an affirmative majority vote from registered citizens of the county seeking to change its seat. Bonner v. Jackson, 158 Ark. 526 (1923). An act from the General Assembly was held by the Supreme Court under Bonner v. Jackson not to be the means of elimination or removal of a county seat.

Please note that temporary county seats are only for new counties, and the location of the county seat is set by the General Assembly in the Act which authorized the formation of the new county. Ark. Code Ann. § 14-14-307(a) (1987). The temporary location of the county seat in a new county is considered the permanent location until changed under the proper procedure. Ark. Code Ann. § 14-14-307(b) (1987).

Are there really 10 counties with dual county seats in Arkansas? Do the citizens and county officials in these 10 counties truly know whether their county has two county seats?

Currently, 10 counties have split judicial districts. Article 13, § 5 of the Arkansas Constitution authorizes Sebastian County, if it so chooses, to establish two districts and two county seats. See: Robinson v. Greenwood District, Sebastian County Quorum Court, 258 Ark. 798, 799, 528 S.W. 2d 930 (1975). Many of the counties reputed to have dual county seats had their judicial districts split through legislative action between 1875 and 1913. Generally, these acts established new judicial districts.

There is nothing in our Constitution which prohibits the Legislature from dividing a county into two judicial districts and defining the power and jurisdiction of the courts therein situated. Williams v. Montgomery, 17 S.W.2d 875, 875 (Ark. 1929). This notion was seen more recently in Parker v. Crow, 368 S.W.3d 902 (Ark. 2010), with the court ruling Act 74 of 1883 which split the judicial district of Carroll County, was constitutional and has not been superseded by subsequent law. However, do these acts create a new county seat? Or a dual county seat? Or do these acts merely create dual judicial districts and not affect the county seat? Act 74 of 1883 established a Western Judicial District in Carroll County, yet referred to Berryville as the county seat. Act 133 of 1885

County Seats

split Prairie County’s judicial districts while stating Des Arc will remain the county seat.

Some early statutes and court opinions used the terms “seat of justice” and “county seat” interchangeably. The terms “seat of justice” and “county seat” can be interchanged with some limitations, however “It is apparent that a seat of justice is not always a county seat, although a county seat is perhaps always a seat of justice.” Parker v. Crow, 368 S.W.3d 902, 911 (Ark. 2010).

In basic terms, the “seat of justice” of the county encompasses the legal activities of the county. The Arkansas Supreme Court acknowledged this difference and defined the seat of justice as a place where “the courts sat and administered justice, and the public officers kept their offices, and performed the functions of their offices.” [Law v. Falls, 159 S.W. 1130, 1131 (Ark. 1913)]. The “county seat” encompasses the government aspects of a county, as well as the town in which the county and other courts are held, and where the county officers perform and discharge their duties. Williams v. Reutzel, 60 Ark. 155, 29 S. W. 374; Graham v. Nix, 102 Ark. 277, 144 S. W. 214. The county seat does not consist merely of the courthouse and jail, but also of the territory of the town designated as the county seat. McGregor v. Cain, 7 S.W.2d 13, 14 (Ark. 1928). Judicial districts are the territorial jurisdiction of state district courts. These judicial districts are determined by the Arkansas General Assembly.

How do you eliminate dual judicial districts?

In 2010, a case appeared before the Arkansas Supreme Court in which a circuit court judge attempted to merge the two judicial districts of the county. This attempted elimination of two judicial districts (or by its correct alternative, merging of two judicial districts into one judicial district) was found by the court to be an overreach of the judge’s power under Amendment 80 of the Arkansas Constitution. Parker v. Crow, 368 S.W.3d 902, 909 (Ark. 2010). In the courts conclusion, it made as a final point and for clarification that the power to establish these districts lies with the General Assembly, citing Amendment 80, section 10 of the Arkansas Constitution, which reads as follows: “The General Assembly shall have the power to establish jurisdiction of all courts and venue of all actions therein, unless otherwise provided in this Constitution, and the power to establish judicial circuits and districts and the number of judges for Circuit Courts and District Courts, provided such circuits or districts are comprised of contiguous territories.”

How do you legally determine whether or not a county has a single county seat or is to be considered having two county seats?

Continued From Page 26 <<<

An opinion of the Attorney General lacks the power of a declaratory judgment. The opinions under Ark. Code Ann. § 25-16-706 are for purposes of interpretation of existing law for certain officials. The Attorney General is not charged with the responsibility or the authority to adjudicate facts or render judgments.

A declaratory judgment may be more appropriate. A declaratory judgment is a judgment given by a court which adjudicates the rights of parties. When disputes arise concerning private citizens or public officials about the meaning of the Constitution or statutes, a declaratory judgment is especially appropriate. McDonald v. Bowen, 468 S.W.2d 765, 767 (Ark. 1971). In Arkansas, procedure for declaratory judgments is found in Ark. R. of Civ. P. 57, and located in § 16-111-101 to § 16-111-111 of the Arkansas Code.

Can a county seat move to another county?

During the 1830s to 1880s, county borders were evolving in multiple ways. New counties were being created causing existing borders to be redrawn. Neighboring counties were also redrawing the borders separating them to follow along natural borders such as rivers. A number of counties were divided by large rivers which may have been difficult to cross for county residents. Redrawing this border shifted cities from one county to another. Some of the cities listed above were affected by this type of realignment. The question arises, were these cities voted in as county seats in a different county than which they reside in today? Would you find the voting records creating a county seat in a different county than it exists today? And would those results be valid?

The issue of dual county seat status creates an in-depth discussion combining present day and historical facts and issues. The purpose of this article is not intended to draw any conclusions as to the validity of a county seat.

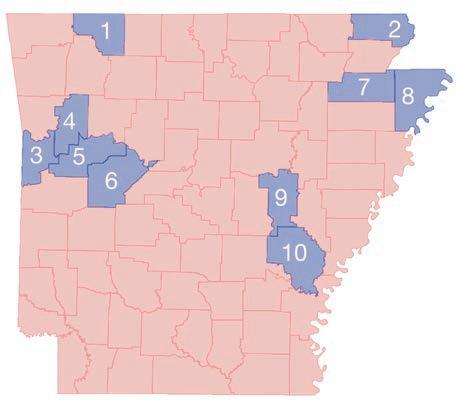

1. Carroll 2. Clay 3. Sebastian 4. Franklin 5. Logan 6. Yell 7. Craighead 8. Mississippi 9. Prairie 10. Arkansas

Past, future of dual-seat counties in Arkansas

By Jay Barth and Barrett Goodwin For County Lines

One quirk of local government in Arkansas is the significant number of “dual county seats,” that is two communities in the county that have a courthouse and are seen as a center of county government. Across the 3000-plus counties and county equivalents in the United States, only 28 have two county seats. Arkansas and Mississippi contain the majority of dual county seats across America, those from outside the state often are curious about the origins of the practice. In total, 10 Arkansas counties are described as having two county seats. However, in recent years, legal questions have arisen about the legitimacy of nine of them. As a result, the next few years may produce more conversations — in legal proceedings and coffee shops — about the somewhat counterintuitive practice of, making two municipalities “the principal site” for county government business.

The legitimacy of one of the dual county seat arrangements is unquestioned. Arkansas’ 1874 Constitution clearly states Sebastian County may have two county seats in Article 13, Section 5: “Sebastian County may have two districts and two county seats, at which county, probate and circuit courts shall be held as may be provided by law, each district paying its own expenses.”

The allowance of a dual county seat system in Sebastian emanated from the chaos in the county in its early years regarding the location of the county seat produced by competition between Greenwood and the upstart town of Fort Smith. Sebastian County was created in 1851 from territory taken from three other counties. The first county seat was at Eaton Tatum’s home in Jenny Lind, but it quickly moved to Greenwood. This was controversial, however, as Fort Smith was a growing boomtown in the northern part of the county thanks to its place as a stop on the wagon trail headed to the California. In 1852, the county seat shifted to Fort Smith. It was then moved back to Greenwood from 1854 to 1861. The solution to this feud was found in 1861, when the Arkansas Legislature divided the county into a Northern district seated in Fort Smith and a Southern one seated in Greenwood. The 1874 Constitution ratified the permanence of this set-up.

Article 13 suggests other counties can choose to have additional county seats. However, the Constitution is also quite clear that the county’s voters must make any decision about any creation (or alteration) of a county seat at the ballot box. As Section 2 states: “No county seat shall be established or changed without the consent of a majority of the qualified voters of the county to be affected by such change…”

County

Arkansas

Carroll

Clay

Craighead

Franklin

Logan

Mississippi

Prairie

Sebastian

Yell

Seats (Creation Date)

DeWitt (1855) Stuttgart (≈1928) Berryville (1875) Eureka Springs (1883) Corning (1881) Piggott (1891) Jonesboro (1859) Lake City (1883) Ozark (1838) Charleston (1901) Paris (1873) Booneville (1901) Osceola (1833) Blytheville (1901) DeValls Bluff (1873) Des Arc (1877) Greenwood (1851) Fort Smith (1861) Danville (c. 1844) Dardanelle (1875)

Past

However, in most of the other counties with a second county seat, it has been the state legislature’s lawmaking process rather than a county’s voters that has “created” the second county seat. Between 1875 and 1913, laws were passed by the General Assembly mandating the splitting of the “judicial districts” of a county across a number of counties. The legislation used the term “judicial district,” meaning that judicial proceedings could be carried out in courthouses in two locations in the county, but the pieces of legislation that allowed two centers of court activity in a county also explicitly stated that one town should remain the “county seat.” However, in the eyes of the public, these counties—with two buildings where court was held and other county business such as the issuance of marriage licenses were carried out—now had two “county seats.”

In recent years, two court cases have challenged this notion. Circuit Judge Ken Crow, who had written a master’s thesis on the topic of dual county seats, declared in two separate rulings in 2010 that the General Assembly’s 1883 law that had created separate Eastern and Western judicial districts — in Berryville and Eureka Springs, respectively — was in violation of Article 13 of the Constitution in that it had de facto created two separate counties on each side of the Kings River. As a result, judicial proceedings could not properly take place at the Eureka Springs court house. Later that year, however, the Arkansas Supreme Court overturned Crow’s rulings and made clear that two operating courthouses could exist in Carroll County as long as the county government wanted. The ruling did restate that Berryville was, indeed, the true “county seat” of the Ozarks county as it had been since 1875.

In 2015, county government officials in Mississippi County grappled with the closing of one or both of the courthouses — in the official county seat of Osceola and the long-time second judicial district in Blytheville — because of the cost of maintaining old buildings.

The city of Osceola retained former state Attorney General Dustin McDaniel as its attorney and the county leaders ultimately decided to avoid the conflict.

No matter their legitimacy, why does Arkansas have so many dual-seat counties?

In several cases, it was simple geography as barriers such as rivers cut counties in half, making it difficult for many residents to reach their courthouse. Like the Kings River that divided the booming Eureka Springs from the remainder of Carroll County, frequent flooding along the White River divided Prairie County. Prairie County was created in 1846, with its seat in Brownsville. After the Civil War, the county seat was moved to DeValls Bluff in 1868, as it had been a major supply depot for the Union army in the region. In 1875 the county seat was moved again, this time to Des Arc, Prairie County’s traditional main city. This proved to be less than ideal, however, because frequent flooding along the White River divided the county and made reaching Des Arc difficult for those living south of the White River. The solution was

Continued From Page 27 <<<

Top: Carroll County Courthouse (Eureka Springs, 1883) Bottom: Carroll County Courthouse (Berryville, 1875)

to divide the county in 1885 into two judicial districts: a Northern one in Des Arc and a Southern one in the former county seat of DeValls Bluff.

Other counties lacked such barriers but were particularly large and two seats made sense in the days of horses and buggies. Logan County began as Sarber County in 1871, named after a Republican state senator named John Sarber. The original seat was a town called Ellsworth, but an election was held to change the seat to Paris. In 1875, Paris became the county seat of a new Logan County renamed after an early settler because many Democrats were none too fond of having their county named after a Republican following Reconstruction. Paris proved to be a long way away for the residents of the southern part of Logan, as a trip to Paris took two days due to poor transportation. This part of the county wanted a courthouse of their own, so in 1901 Logan was divided by the General Assembly into two judicial districts. The Northern district was to remain based in Paris, with the Southern district seat chosen by voters to be the historic Booneville (which won out over Magazine). Paris remained the main county seat, housing all pre-1901 records for Logan County.

In other cases, as was the case in the contested Sebastian County, a new town “boomed” with population and began to demand the clout of a county seat. In a state where local government was the most prominent government in folks’ lives, being able to have a county courthouse and be the center of a judicial district meant a lot for the prestige of a community.

Over time, the block of land that was the original Arkansas settlement was broken up into numerous different counties until all that was left was officially organized as Arkansas County. This resulted in the need for a new county seat that was more centrally located than the original Arkansas Post. A location was selected, and the new resulting community was, following the drawing of a name from a hat, named DeWitt in honor of former New York Governor DeWitt Clinton in 1855. However, Stuttgart, incorporated in 1889 as a settlement of German immigrants, found its footing at the turn of the 20th century as a booming agricultural center. Soon to be known as the rice capital of the world, Stuttgart became the judicial seat for the northern half of Arkansas County in the early 1920s due to its growing size and obvious clout in the county. Their courthouse signifying this new status was built in 1928.

For the time being, dual county seats remain a distinctive reality of local government in Arkansas. However, with the cost of maintaining older courthouses growing every year, it is likely that future consolidation issues will arise. Moving forward, balancing history with fiscal pragmatism is likely to become increasingly difficult. Courts may be forced to make final determinations in the conflict between Article 13 and long-time practice.

Jay Barth is M.E. and Ima Graves Distinguished Professor of Politics and Bill and Connie Bowen Odyssey Professor at Hendrix College. Barrett Goodwin is a senior Politics major at Hendrix who collected information and drafted portions of this piece.

Sources: Various entries of The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (http://www. encyclopediaofarkansas.net/)

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas. 1962. Arkansas Almanac 1962. Little Rock. The Arkansas Almanac Company, Inc.

Banks, Wayne. 1959. History of Yell County, Arkansas. Van Buren, AR: The Press Argus.

Edrington, Mabel F. 1962. History of Mississippi County, Arkansas. Ocala, FL: Ocala Star-Banner. Field, Hunter. “Dual County Seats Claimed by Some Counties.” Arkansas Democrat Gazette, 20 March 2016.

Goodspeed’s History of Craighead County, Arkansas. 1964 (1889). Van Buren, AR: The Press Argus.

Hanley, Ray and Hanley, Steven. 1999. Sebastian and Crawford Counties, Arkansas. Arcadia Publishing.

The History and Families of Carroll County, Arkansas. 2003. Berryville, AR: Carroll County Historical and Genealogical Society.

Logan County, Arkansas: Its History and its People. 1987. Paris, AR: Logan County Historical Society.

Snowden, Deanna, editor. 1986. Mississippi County, Arkansas: Appreciating the Past, Anticipating the Future. Little Rock: August House.

75 Counties - One Voice

AAC names 2016 scholarship recipients

Students plan to study accounting, nursing, engineering and more

The Association of Arkansas Counties recently announced its 2016 AAC Scholarship Trust recipients. AAC established the trust in 1985 to provide college financial assistance to the children, stepchildren and grandchildren of Arkansas county and district officials and employees. AAC has since awarded more than $185,000 in scholarships.

Along with AAC, the following county associations contribute to the scholarship trust annually: The County Judges Association of Arkansas, the Arkansas County Clerks Association, the Arkansas Circuit Clerks Association, the County Collectors Association of Arkansas, the Arkansas County Treasurers Association, the Assessors Association of Arkansas, the Arkansas Association of Quorum Courts and the Arkansas Sheriffs’ Association.

• Kaylee Bundy – Kaylee is a 2016 graduate of Valley Springs High School and the daughter of Tammy Bundy, who works in the Boone County Clerk’s office. Kaylee plans to attend Missouri State University in Springfield to pursue a Masters of Accountancy degree.

• Megan Renee Davidian – Megan graduated from Fayetteville High School East this year and is the daughter of Edit Waynette Davidian, who works in the Washington County Collector’s office. She will attend

the University of Arkansas this fall to study engineering.

Kaylee Bundy Megan Renee Davidian

Lacey Howard Kasey Keith High School and is the daughter of Polk County Road Department Foreman Jeff Howard. Lacey will attend Rich Mountain Community College in Mena and plans on a career in nursing.

• Kasey Keith – Kasey is a sophomore at the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith. Her father, Chris Keith, grandfather, Bill Grill, and grandmother, Glenda Grill,

all are employed by Crawford County. Kasey is planning to pursue a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing.

• Ashton Kimbrough – Ashton is a 2016 graduate of Bryant High School and is the daughter of Saline County Justice of the Peace John Kimbrough. She will attend the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville as a pre-med student.

• Thomas Worley – The son of retired Bradley County Circuit Clerk Cathy Richardson, Thomas is a 2016 graduate of Harmony Grove High School in Camden. He will attend Ouachita Baptist University, where he plans to study business.

• Jared Dale Flemens – Jared graduated from Mena High School in 2016 and is the grandson of retired Polk County Deputy Gene Hendrix and his wife, Vicki, who is a deputy and jail administrator. Jared has plans to study psychology at the University of Central Arkansas.

• Kaitlyn Dahlke – Kaitlyn, the granddaughter of Hot Spring County Treasurer Mary Cansler, is a sophomore at Henderson State University. She is studying nursing. This

Ashton Kimbrough Thomas Worley

Kaitlyn Dahlke is the third year Kaitlyn has received an AAC scholarship.

• Chandler Konecny – Chandler is a 2016 graduate of Stuttgart High School and the granddaughter of Prairie County Justice of the Peace Buddy Sims. Chandler will attend the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, where she will pursue a bachelor’s degree in biology. She plans to attend medical school and specialize in pediatrics.

Chandler, who teaches dance, is this year’s recipient of the Matt Morris Scholarship.

The scholarship was established following the death in 1999 of Matt Morris. Matt was the son of Searcy Mayor David Morris, who is a former AAC employee. Matt was an Arkansas Razorback baseball recruit. The scholarship is funded by donations made in Matt’s name and by the County Judges Association. It is awarded each year to an applicant who reminds the scholarship committee of Matt, either through their

sports involvement or by helping others.

• Shawna Marie Martin – Shawna is a 2016 graduate of Cotter High School. She is the granddaughter of Laurel Don Reed, who works in the Baxter County Road and Bridge Department. Shawna plans to attend Arkansas State University in Jonesboro, where she will study journalism with an emphasis in photojournalism. Shawna is the recipient of the Randy Kemp Memorial Scholarship. Randy served as AAC communications director from July 2008 until his death in August 2011. The scholarship is funded exclusively by the annual AAC golf tournament and awarded each year to an applicant who plans to study journalism or mass communications.

Chandler Konecny Shawna Marie Martin

cover story

Working in Tandem

Open line of communication defines professional relationship between state Rep. Michelle Gray and Izard County Judge David Sherrell.

Story and Photos by Christy L. Smith County Lines Editor

Friendly banter punctuates the conversations between Izard County Judge David Sherrell and state Rep. Michelle Gray. The two have known each other for more than 15 years — long enough that they can finish each other’s sentences if they want to.

And they often do.

“Since I’ve been elected, we’ve just had a lot of local issues we’ve had to work through. I’m on the EMS board for the county, and we’ve had a lot of …,” Gray began.

“… difficulty,” Sherrell finished.

“Difficulty. Thank you,” Gray replied.

The two came together this summer at the Izard County Courthouse for the sake of an Association of Arkansas Counties (AAC) job shadowing project that, in the past, has partnered county elected officials with their respective state senators and representatives in an effort to give the state official a better idea of the issues county officials tackle on a daily basis.

But Gray, who was born and raised in the county seat of Melbourne, already has a good grasp of what Sherrell’s job looks like. In addition to EMS issues, they’ve stood side by side during a reorganization of area programs for senior citizens, they’ve gone to battle together over a stretch of highway they thought should be taken over by the state, and they’ve worked in tandem to attract economic development projects to the county.

Almost from the moment Gray was elected to represent Dis-

cover story

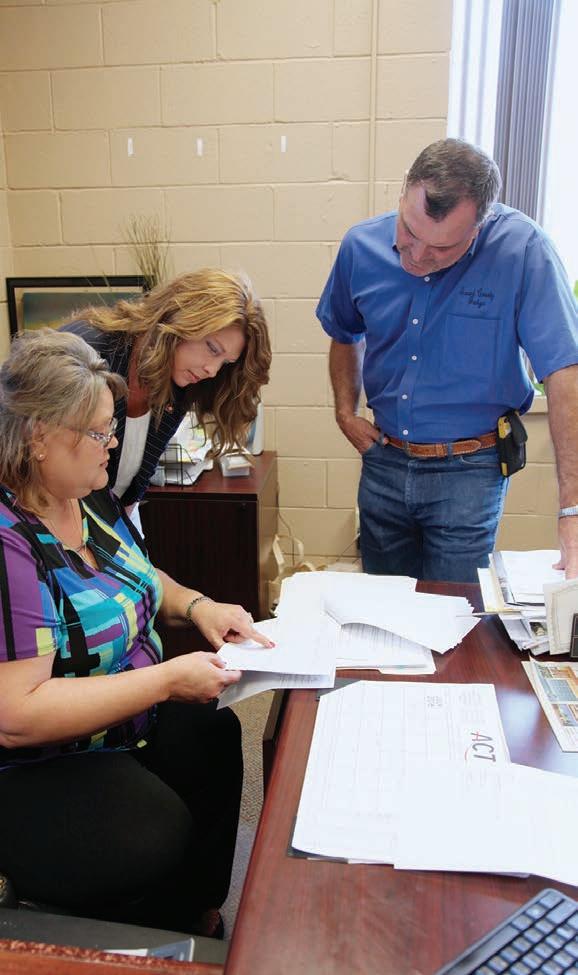

Opposite page: State Rep. Michelle Gray and Izard County Judge David Sherrell stop in the old vault at the courthouse. This page, left: Izard County Assessor Tammy Sanders shows Gray and Sherrell records indicating the assessed property value in the county has grown from $65 million to $169 million in the last 22 years. Top: Gray and Sherrell stand outside the Izard County Courthouse in Melbourne. Bottom: Izard County Sheriff Tate Lawrence discusses the history of the jail with Sherrell and Gray.

trict 62 (Izard County and parts of Sharp, Stone and Independence counties) in the state House of Representatives, the two have shared an open dialogue. Theirs is a particularly open dialogue because Gray lives in Melbourne and can be at the Izard County Courthouse more readily.

“I wouldn’t know what all the county needs without talking to him,” Gray said. “There are times he’ll call and tell me about a problem that I had no idea about, and I can contact the right people at the state to facilitate change much quicker.”

Sherrell said he is grateful to have a good relationship with his legislator.

“If you didn’t have that, you’d be talking to a wall when you called down there to Little Rock,” he said. “She’s in touch with our problems here, and she tries to help on that end.”

Izard County is a class 2 county with a population right at 13,700. The three largest towns are Melbourne, the county seat; Horseshoe Bend, a resort retirement community; and Calico Rock, which sits on the bluffs of the White River.

Sherrell, who also has lived in Melbourne his entire life, is serving his third term as county judge. Gray is running unopposed for her second term in the House. Sherrell’s wife works as a nurse practitioner at the medical clinic owned by Gray and her husband. And Gray’s three children like to go fish in Sherrell’s pond.

“We text and call each other all the time,” Gray said.

And Gray said all the state legislators are open to communications from county officials in their districts.

Tandem

Continued From Page 33 <<<

“They all love texts and hearing from their constituents,” she said. “Sometimes there are unintended consequences to things we do. A lot of times they can see what we don’t see.”

“Or vice versa,” Sherrell added. “She’s called me about bills that affect counties and asked if I’ve read this bill. I go in and read it and give her my opinion.”

During the job shadow interview, Sherrell led Gray on a tour of the Izard County Courthouse and annex, walking from one county elected official’s office to the next. Each stop was like a reunion of old friends. After all, many of the county elected officials in Izard County have held these seats for numerous years — County/Circuit Clerk Shelly Downing worked as deputy clerk for 18 years before being elected to the position that her sister, who now serves as mayor of Melbourne, vacated; Sheriff Tate Lawrence is in his 12th year as sheriff; and Tammy Sanders has worked for the county for 28 years, the first six years in the collector’s office before being elected assessor.

While at the annex next door to the courthouse, a constituent walked in and began discussing a road issue with the judge. Sherrell explained that roads and bridges are a constant concern.

“Our road department [budget] is just a million, five hundred thousand,” he said. “It’s probably one of the lowest in the state. We just do the best we can with what we’ve got.”

Sherrell said Izard County has 1,200 miles of gravel roads and 200 miles of paved roads. The $1.5 million he mentioned comes from the turnback received from the state and “the little bit of taxes we get off of the property tax.”

“There was a gentleman who came in the other day and was talking about how much he paid in taxes,” Sherrell said. “He paid $657 in taxes and $27.50 of that went to the road department. He lives a mile and a half down a dirt road, and he was a little disgruntled that he didn’t have a better road [since he was] paying $657. The schools get about 86 percent of it, and there’s nothing we can do about that.”

Sherrell said a large chunk of his road department budget — about $700,000 — goes to labor. Fuel costs the county about $250,000 a year and parts run about $100,000 a year.

“So you can see what we have left to actually do maintenance on the roads,” he said, noting that the $192,000 Izard County receives per year in state aid funding helps. Still, he said, he has 22 full-time employees in the road department but needs about 35.

“We just can’t afford it,” Sherrell said. “The road foreman gets in there and helps them. Fortunately, I know how to run all the equipment, so I do the same thing. Last week, we redid a road — the road foreman and I. He was on the excavator, and I was on

the dozer. Now the truck driver brought the gravel to us, but he and I fixed the road. It helps that he and I both know how to do this when we are short handed.” The court is housed on the second floor of the Izard County Courthouse annex, and court happened to be in session that day. It led to a discussion of how well the Izard County Drug Court is working. In fact, Assessor Tammy Sanders said she is mentoring a young lady who is going through the program, trying to put her life back together. She had submitted job applications, was trying to get her own apartment and working toward regaining custody of her children. “I’ve been watching her grow from way down here for the last couple of years,” Sanders said, motioning with her hands. The drug court in Izard County also serves Fulton County, and it’s a 5-year-old program. Reporting, random drug testing and group sesDuring the job shadow interview, Sherrell led Gray on a tour of the Izard County Courthouse and annex, walksions are on the menu for those who go through drug court. They also have to make attempts to gain employment, and ing from one county elected official’s office to the Izard County itself has hired four or five people next. Each stop was like a reunion of old friends. from the program. Gray said she has a positive opinion about the drug court program with its goal of diverting nonviolent offenders from already overcrowded jails and prisons. “I try to be open minded. It wasn’t something I thought would work, but once I saw it in action and someone took time to explain it to me, I saw how it actually was working,” she said. “You think about someone like her [the woman Sanders is mentoring] — say you put her in prison and she stays three, five years, then she gets out. She goes right back to it because she doesn’t know anything else. She can’t go out and get a job. She has no trade. It repeats the cycle. So this hopefully helps to break that cycle.” A constituent also approached Gray during the time she and Sherrell spent at the annex that morning. And that’s where the two officials’ jobs are most similar — they are always on the clock. “I used to be real shy,” Gray said. “Do you believe that?” Sherrell asked of Sanders. “No, really,” Gray said. However, both of them say they’ve gotten used to being approached by constituents while in the grocery store or at a restaurant. And they handle those situations in a very similar fashion: they hear out the constituent, and then logically hash out a solution. “You have to remember that problem to them is huge,” Gray said. “They don’t feel like they’re interrupting you,” Sherrell said. “They just feel like that’s part of your job, and …” “… it is,” Gray finished.

The Association of Arkansas Counties

Working for county officials toward the common goal of effective county government...

www.arcounties.org

Did you know that counties are subdivisions of Arkansas state government?

As such, our county and district elected officials and staffs are like gears in a large and complex engine. AAC’s goal is to keep that engine welloiled and finely-tuned by providing a broad array of:

• Legislative Representation • Education and Training • General Assistance and Research • Publications & Public Information • Protection Options: AAC Risk Management & Worker’s Compensation Programs

AAC serves as the official voice of county government at the state Capitol, and serves as the official spokesperson and liaison of Arkansas counties in dealing with state and federal agencies. The key to the stability and development of county government is in presenting a unified voice to other levels of government. There is much truth in the adage, “There is strength in unity.”

The Association of Arkansas Counties provides training and assistance in solving problems and in developing “best” practices. AAC produces numerous publications to help county officials with both simple and technical questions, so they can get needed answers without having to reinvent the wheel. This information is available through numerous training workshops, helpful brochures and directories, County Lines magazine, and online at the website: www.arcounties.org

Our Mission

The Association of Arkansas Counties supports and promotes the idea that all elected officials must have the opportunity to act together in order to solve mutual problems as a unified group. To further this goal, the Association of Arkansas Counties is committed to providing a single source of cooperative support and information for all counties and county and district officials.

The overall purpose of the Association of Arkansas Counties is to work for the improvement of county government in the state of Arkansas. The Association accomplishes this purpose by providing legislative representation, on-site assistance, general research, training, various publications and conferences to assist county officials in carrying out the duties and responsibilities of their office.