5 minute read

JUNETEENTH :AHISTORYLESSON

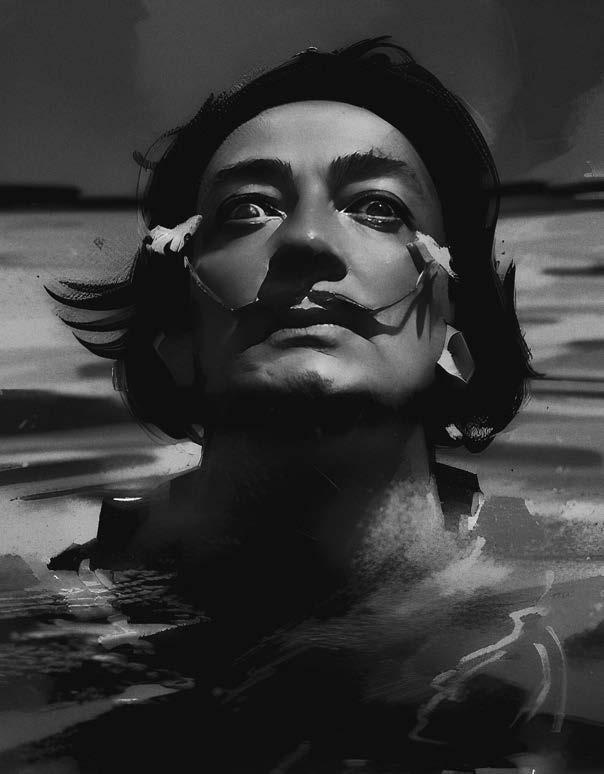

As explained by The National Museum of African American History & Culture, & illustrated by the photographic conceptual art “A Head Full of Stars II“ by Sinenkosi

Msomi / Swaziland

Advertisement

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free.

Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later.

Freedom finally came on June 19, 1865, when some 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas.

The army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree. This day came to be known as "Juneteenth," by the newly freed people in Texas.

The post-emancipation period known as Reconstruction (1865-1877) marked an era of great hope, uncertainty, and struggle for the nation as a whole. Formerly enslaved people immediately sought to reunify families, establish schools, run for political office, push radical legislation and even sue slaveholders for compensation.

Given the 200+ years of enslavement, such changes were nothing short of amazing. Not even a generation out of slavery, African Americans were inspired and empowered to transform their lives and their country. Juneteenth marks our country’s second independence day. Although it has long celebrated in the African American community, this monumental event remains largely unknown to most Americans. The historical legacy of Juneteenth shows the value of never giving up hope in uncertain times.

TheNationalMuseumofAfricanAmericanHistory andCultureisacommunityspacewherethisspiritof hopeliveson.Aplacewherehistoricaleventslike Juneteentharesharedandnewstorieswithequalurgency aretold.

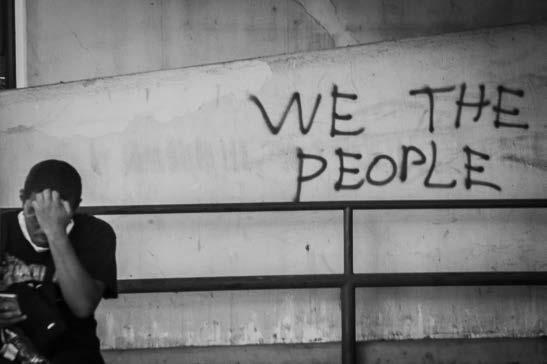

In May of 2020, people all across the world stood up to protest Police brutality and speak for those who were no longer are able. These images were taken over a 3 day period during the protests in Austin,Texas.

Three days.

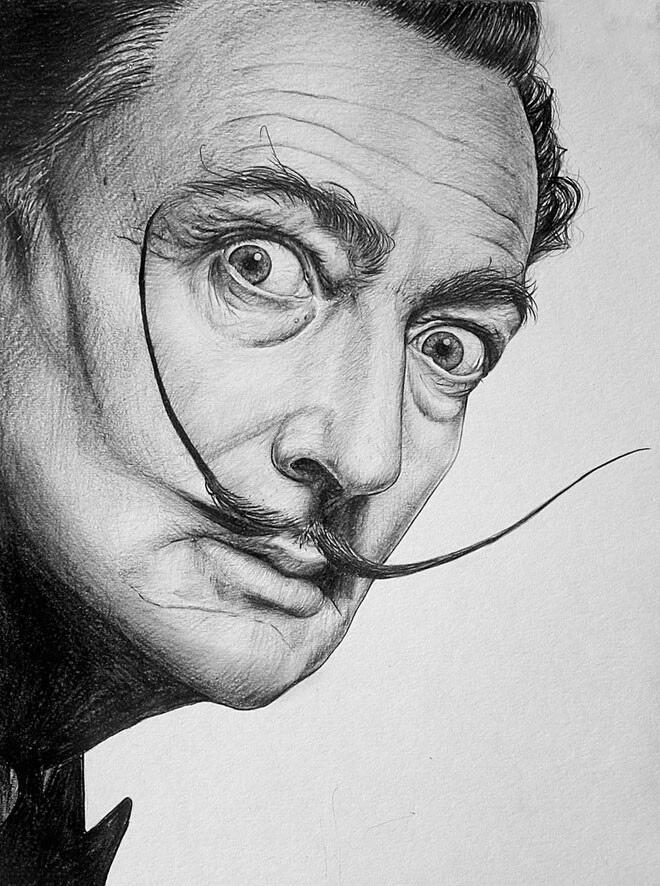

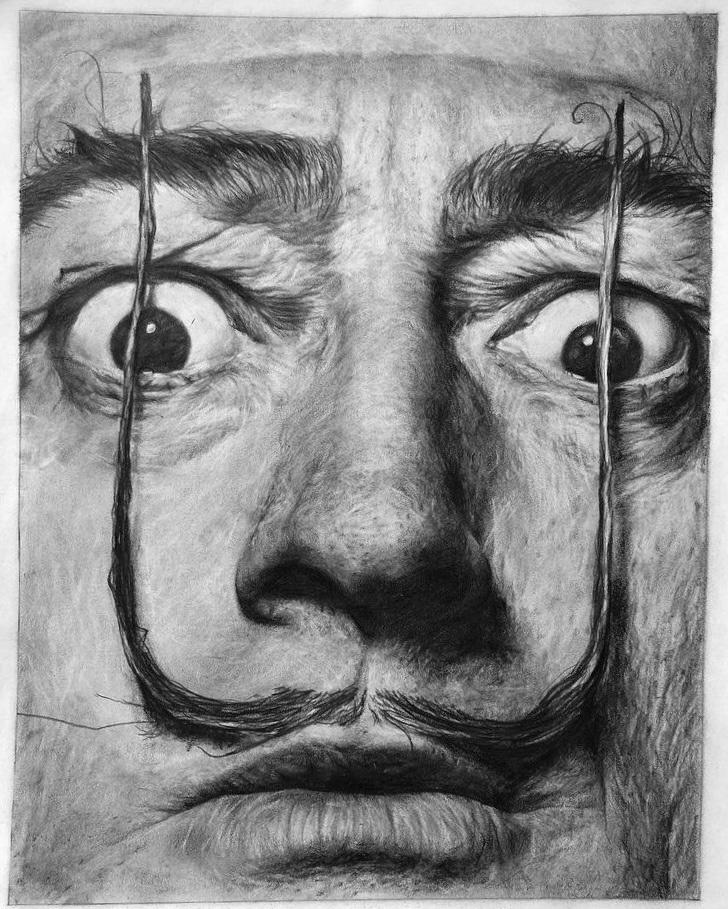

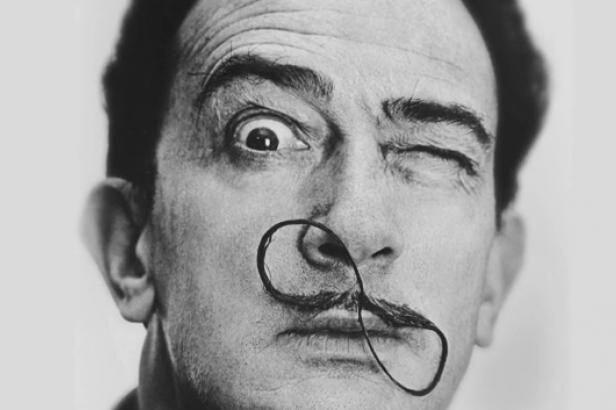

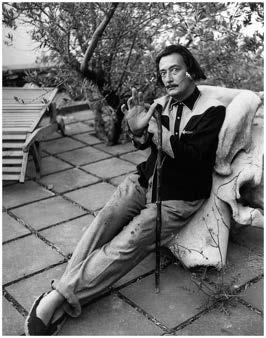

Salvador Dal

Master of the obscure, Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, born the Marquess of Dalí of Púbol in 1904 would turn the whole world on it’s head, creating with his unique art style an entire movement that would change the way we look at and interact with art forever.

You can say ‘Salvador Dalí’ or refer to his style to just about anyone the world over and they immediately know who and what you’re talking about. Though he isn’t the father of the surrealist genre, it’s safe to say Dalí IS Surrealism.

Formally educated in fine arts in Madrid, Spain, young Salvador was—like most artists of his time— originally influenced by the Renaissance masters and Impressionism. During his intensive studies, he grew fond of the Cubism and avant-garde movements. He would not try his hand at Surrealism until the late 1920’s. However, finding it to be enticing enough to hold his interest and grant him more imaginative and intellectual freedom than his previous loves, it’s the genre that ultimately stuck.

“His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in August 1931, and is one of the most famous Surrealist paintings”—in the world, and throughout time. [Wikipedia] But Dalí was more than his art. He cultivated a rebellious dadaist attitude and honed it into an entire lifestyle. He presented ever-stylish, even in the most simple classic suits, demanding through his appearance to be taken seriously. And he would become more brazen and empowered in his style choices the older he got. Salvador Dalí’s iconic mustache, for instance, would become his personal trademark.

This personal expression had to be extremely liberating, considering he resided in France for three years during the Spanish Civil War—1936-1939. He wouldn’t move to the US until 1940. Within 9 years, he became lucrative and respected as an eccentric fine artist.

“He returned to Spain in 1948 where he announced his return to the Catholic faith and developed his "nuclear mysticism" style, based on his interest in classicism, mysticism, and recent scientific developments. Dalí's artistic repertoire included painting, graphic arts, film, sculpture, design and photography. He also wrote fiction, poetry, autobiography, essays and criticism. Major themes in his work include dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, religion, science and his closest personal relationships. To the dismay of those who held his work in high regard, and to the irritation of his critics, his eccentric and ostentatious public behavior often drew more attention than his artwork.” [Wikipedia]

Love him or hate him, Dalí had the ability to provoke and polarize, inflating his ego to monumental proportion only to bash it with humbling irony by pointing out even his own absurdity. He was a character who took himself completely seriously, while simultaneously appreciating his own fallible nature. To this day, he acts as a carnival mirror reflection of our own psyche. In so many ways, he embodied his art, taking it from the canvas to the real world, from the way he conducted himself to the collaborative crossovers he would venture.

—Dalí

One such historically iconic collaborative relationship Salvador would develop with the equally artistically-adventurous fashion visionary, Elsa Schiaparelli. “Elsa Schiaparelli was the first to design a jumpsuit. Salvador Dalí made the first artist video. Schiaparelli held the first fashion show set to music. Dalí introduced the world to the art hologram. Their first collaboration was a newspaper print of Schiap’s press clippings in 1935.

The sense you’re supposed to get as a reader is that these two iconoclasts were more than just a wacky mustache and a shoe hat; they altered the course of art and fashion in the 20th century. What’s more is that the irony—the mix of high and low materials, and the multimedia promotional materials that they pioneered—are still used by artists and designers today.

Both started life anonymously. He was given the same name as his parents’ deceased first son; she was named at her christening by a German nanny when her parents failed to come up with any girls’ names. (They were hoping for a boy.) That shared sense of lost identity is perhaps what cast them into the metaphysical and mystical realms. When they met in Paris in the early ’30s, Dalí was an on-the-rise Surrealist and Schiaparelli a well-known designer and a recently divorced single mother. Both were interested in Classicism—the acanthus leaf is a shared motif of theirs—and turning those GrecoRoman ideals on their heads. Each was a master technician, proven by Dalí’s exquisite brushwork and Schiaparelli’s intricate couture beading and tailoring. They both valued irony and shock value, which resulted in some of their most lauded collaborations, like 1937’s Shoe Hat and the aforementioned Lobster Dress (which Dalí wanted shown with a side of mayonnaise). The list of their shared works includes some of fashion’s most surprising and stunning garments, and their creative process seems to be a two-way street, with the designer calling on Dalí to design her perfume bottles, and the artist asking Schiaparelli to interpret his haunting female forms in 1938’s Tear Dress and 1938’s Skeleton Dress.” [VOGUE Magazine, journalist Steff Yotka circa 2017]

It’s for these very reasons we leaned so strongly on this raucous pairing for the majority of the artistic inspiration throughout this, the first issue of PEPPER Magazine’s second year.