62 minute read

Tour Update

from MIX 524 - Aug 2020

by publications

Live

Live By Phone

The Artist’s Perspective on Summer 2020

By Lily Moayeri

No matter what level of success a musical artist has attained, the struggle in the current scenario is similar. Until musicians can perform in a face-to-face setting again, virtual interactions through social media—Instagram in particular—have become one of the only options to connect with fans and bring awareness to their work.

At the time of lockdown, Billboard charttopper and multiple Grammy Award-winning artist Tori Kelly was starting a tour for her third album, 2019’s Inspired by True Events. That soon ended. Donna Missal, who was on an arena tour of Europe, supporting the likes of Lewis Capaldi, was rushed home to the U.S. ahead the release of her second album, Lighter. Second-generation guitarist and songwriter Nile Marr had all his activities stalled: finishing recording an album and cultivating a grassroots following in his hometown of Manchester, England.

Marr has a comedic and natural persona on social media and is topping the coveted 10K mark on Instagram followers. He has a monthly Q&A while he’s getting his hair dyed, a communal feeling to his posts, an observational slant to his stories, and is good at building momentum. By contrast, prior to the shutdown, Missal, who has more than 80K followers on Instagram, had never used social media to bond

Tori Kelly, in June of this year, and in her Delta H Design home studio, which serves as the set for her Instagram Live show, QuaranTEA With Tori.

with fans as such, and certainly not as a performance space.

“I always thought of these platforms as a place to give information,” Missal says. “They’re not built for creating and sharing experiences. For my last album, This Time, I was in all these different cities performing the record, doing a ton of promo. I was going to radio stations, doing live performances for late night TV. I promoted it in a live, present way. I never did anything on social media.”

Kelly, on the other hand, got her start on YouTube as a teenager and is very comfortable on social media platforms, where she has 3 million-plus followers on Instagram (and YouTube). Two weeks into the lockdown, Kelly started “QuaranTEA with Tori,” a daily series on Instagram Live. It was named by her fans after her “Tea with Tori” pre-show meetand-greets. Kelly is fun and casual in the series, where she sometimes performs on her own and sometimes beings in a few famous friends, such as Demi Lovato and Alessia Cara.

“I only did four shows of my tour before it got cut off, so it felt really natural to transition to performing online because I was already in performing mode, singing every day,” says Kelly, who hosts QuaranTEA with Tori out of her acoustically treated home studio. “In a way, it felt like going back to my roots. I didn’t want to overthink it or make it this big production.”

IN NEED OF OUTLETS “Trying to be an artist is difficult, especially when your outlet is playing live and there is no outlet for you,” Marr adds. “You can’t play gigs, a lot of people aren’t going to make records, and maybe you want to wait it out. I can’t do that. If I’m going to tell people I’m a musician, I need to act like I’m a musician every day.”

Marr has released the three-song EP Still Hearts during quarantine, plus the single “Are You Happy Now?” He has more singles lined up over the course of the next few months, leading up to an album at the end of the year. He has hosted a Q&A with a longtime music friend from his car. He has been a guest on three podcasts: Gigwise, Underground England and Groupie Therapy. He has done an Instagram Live performance for famed guitar shop, Chicago Music Exchange, for Jimmy’s, a gastropub with live music in Manchester, and for United We Stream Greater Manchester curated by Night & Day, where Marr had a residency. All but the last have been streamed from his home.

“I want there to be a way to do livestreams with better audio quality,” says Marr. “I don’t like singing into my phone. I recognize people like it and aren’t bothered by it. But if I’ve got a new song and I’m going to play it on the livestream, I want it to sound brilliant. People are already looking at their phones more than they would normally because they’re inside. I’m asking someone to sit with their phone for 25 minutes as I play into it. I want to sound good. I struggle with the fact that I could hook up a microphone and make it sound better, but I don’t know how to do that yet.”

Missal sometimes has to work around her three housemates, letting them know in advance when her livestreams are scheduled and asking them to stay off the wi-fi, turn off their Bluetooth and remain quiet, giving her the living room, which has favorable lighting and whose vaulted ceilings give her the best acoustics.

Even so, Missal is not able to present her songs without assistance. She plays enough piano and guitar to write songs, but not enough to perform them. She asked her band members to send through their parts, which she has running as backing tracks off one laptop through a Bluetooth speaker. She has a second laptop with lyrics and her notes about the livestream, which

Donna Missal

Donna Missal at home in the studio; she admits that it hasn’t been easy to adjust to social media as her primary performance outlet.

quite often has a charity aspect to it. She has her phone propped up for the actual performance, creating a command center of sorts. This is the setup she had for a Vevo livestream performance for Consequence of Sound.

“I haven’t spent my time as an artist learning self-reliance,” she admits. “I had to reevaluate my standards, understanding that it wasn’t going to be like a live show, it wasn’t going to sound great, but it was going to be the best that I could do. I had to get over that mental hurdle in order to even agree to participate.

“I sing so loudly, and the phone does this crazy throttling thing where if you sing too loud, it is not conducive,” she continues. “It automatically realizes the level is peaking and pulls the volume back suddenly. Luckily, the audience on the receiving end, they don’t really care. The only thing I found people having a hard time with is if your connection isn’t strong enough and you’re glitching. It’s really hard to watch that. It can ruin the performance.”

Kelly also had to improve her wi-fi signal, as neither her home nor her phone service provider were powerful enough. Her intention, however, is to keep her streams as stripped down as possible to go back to her early YouTube days. Kelly has performed on Good Morning America from her home and participated in Instagram Live interviews with E! News and Access Hollywood, as well as Human to Human 2020, a Facebook Live donation event. For these she has had to up her game with a ring light and a Sony C800G microphone and pop screen, while running her audio off Apple Logic Pro. ON STAGE, ALONE IN THE HOUSE For his United We Stream performance, Marr was asked to come to a large theater in the Greater Manchester area. He came on his own armed with his guitars. Ahead of time, disinfected microphones, color-coded per artist, were positioned on stage. His performance and interview were filmed professionally with less than a handful of people in the cavernous space. As low-key as this experience might seem to the viewer, Marr needed a solid week of preparation in order to pull it off.

“I had not been singing loudly, outwardly, and I had not been singing enough,” he says. “You have to be gigging to get back that vocal ability you’re used to. I had to learn how to play acoustic, which I love, but don’t often do. I’m used to going to new tunings really quickly live when I’m on electric because I don’t have a tech. On acoustic, it’s completely different and there’s no applause break, there’s just people waiting on the stream.”

Even though he was playing to the bare bones staff at United We Stream, Marr still prefers that to performing to his phone. “What people

Musician/composer Nile Marr has been active on social media, and he’s been busy professionally, from solo on stage to scoring movies.

don’t realize,” he says, “even just playing on the phone in my house, I still treat that like a gig. I get worked up before. I’ve got the adrenaline rush, but I don’t get the release. I get nervous playing into my phone. I want people to like it more than when I’m at a gig. Playing through my phone, I want people to feel like bringing me into their home and deciding to look at their phone for 30 minutes without changing apps, without doing anything. I want them to feel like it was worth it.”

Marr is not alone in feeling this way. Missal, who after the first couple of shows in a tour hits her groove and is comfortable and confident, has gone back to square one with livestream performances. She says: “I’ve never been more nervous. I get sweats. My face gets flushed. I feel intense anxiety. Once you’ve done everything that you can to set the livestream up, you have to still go through the process of performing into, essentially, a mirror. Sometimes to get the notes out, you just have to look like a crazy person, and that’s got to be okay.”

“Performing is a big circle of energy coming out of the performer to the audience and then the audience gives the energy back to the performer,” she continues. “When you’re performing into your phone, watching this little marker of who’s there and who’s leaving and who’s coming, the comments are scrolling, it’s not a cyclical experience. It’s no longer about passing and sharing of energy, it’s about giving yourself to something and you don’t get anything back.”

Nevertheless, it has been a productive time for Missal, who tapped her record label to purchase Logic and a Universal Audio Apollo Twin, and is teaching herself to use those from what she has absorbed working in studios and via YouTube tutorials.

Kelly, who received Logic as a Christmas present when she was 15 and learned how to record herself years ago, has written and recorded an EP, Solitude, which sonically is more in touch with her origins as an artist and is more reflective of where she is now than where she was at the time of Inspired by True Events.

Marr has completed the soundtrack for the upcoming Ron Howard film, Hillbilly Elegy, with Hans Zimmer and David Fleming. And he has returned to writing songs on acoustic guitar, which is how he got started as a songwriter. He is finding that with his mind unoccupied by soundtrack responsibilities and live gigs, ideas are free-flowing and fast.

Says Marr, “For bigger artists, this has been a massive hit. For an artist at my level, it might slow me down, but people have gotten hyperfocused and close to the artist because you can’t access them anywhere else. I like the live interaction experience.”

“I feel like I’ve really reconnected with fans,” Kelly says. “That’s been awesome. Whatever coming out of quarantine looks like, I want to keep that connection, even if it means spontaneously going on Instagram Live and doing an impromptu jam session, or hopping on chatting with people. I can credit my whole start to posting YouTube videos and going on livestreams, talking with fans and playing very small coffee shops and meeting every single fan afterwards. That is super important to me. I can’t see myself straying from that connection.” ■

The Mix Interview: Shooter Jennings

Artist/Producer Living in the Moment, Searching for Truth

By Sarah Jones

Don’t call Shooter Jennings an outlaw.

The son of country legends Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, raised on tour buses in the company of Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson, it seemed that he was destined for a career smashing the boundaries of country and rock in pursuit of his own musical truth.

Yet Jennings, an ’80s kid at heart, is less interested in the superficial trappings of the modern outlaw movement than its spirit of embracing honesty, however that may manifest. A musician since the age of 5, he left Nashville in his late teens for Los Angeles, releasing two EPs with his Southern rock band Stargunn before focusing on solo work.

Since 1996, Jennings has released eight studio albums and a mountain of live albums, singles and EPs. A hellraising rock and roller, he also spends time at home programming sequencers and crooning busted ballads; in his discography, traditional country records coexist with dystopian concept albums and disco collaborations—from his 2005 scorcher Put the ‘O’ Back in Country; to 2016’s Countach (For Giorgio), a synthy, vocoder-laden tribute to Italian electro-pioneer Giorgio Moroder; to 2018’s Shooter, a return to his rowdy country-rock roots, coproduced and cowritten by longtime friend and collaborator Dave Cobb.

In recent years, Jennings has focused more on producing, collaborating with Jamey Johnson, Wanda Jackson and Billy Ray Cyrus, and helming albums by alt-country artists Jamie Wyatt, American Aquarium and Hellbound Glory.

Since coproducing Brandi Carlile’s landmark By the Way I Forgive You in 2018 with Cobb, Jennings has been immersed in wall-to-wall high-profile rock and country projects, producing Guns N’ Roses bassist Duff McKagan’s solo effort, Tenderness, and collaborating with Marilyn Manson on his 11th studio album, slated for release later this year.

Last year, Jennings, together with Carlile, produced Tanya Tucker’s 25th album, While I’m Livin’. The record—Tucker’s first in 17 years—has been celebrated as one of her finest, drawing comparisons to the late-career work of Cash and Kristofferson and earning Grammys for Best Country Album and Best Country Song and Americana Award nominations for Album of the Year, Song of the Year and Artist of the Year.

Mix sat down with Jennings to talk about evolving musical mindsets, funky vintage gear and the impact he hopes to make as an artist and producer.

How are you weathering sheltering in place? I got lucky; I worked on a bunch of records last year, and they’ve all been coming out during this time. I was working on the Marilyn Manson record in January and February, finishing the mixing and the mastering, and then this thing hit. Then there was a record that Margo Price produced with my mom, Jessi Colter, that I’ve been mixing. Luckily, with my home rig I’ve been able to work the whole way through.

What’s your home studio setup like? It’s pretty unique. I have a Pro Tools HD setup, and I’ve got a bunch of really cool outboard gear. I’m kind of eccentric in the sense that I like to pick up odd versions of things. For instance, everybody uses the UREI 1176 Rev F; I’ve got a Rev H, which is what ELO used in the early ’80s. And I’ve got an LA-2A and an Eventide H910, which is essential in my opinion.

I do it all in the box, but I have one of those little Artist Mix [control surfaces] that Avid makes, and then I’ve got a Lexicon 224, one of the original 1978 units that was actually Neil Young’s personal one. It has his notes on the back—settings and things—so that’s really fun.

I’ve got a bunch of great Spectra 1964 pre’s and a couple of dual Chandler TG2s.When we were mixing the Manson record, [engineer] Spike Stent turned me on to a piece of gear from Overstayer called the Dual Imperial Channel. It’s two channels and has a pre, limiter, EQ, it’s got lots of cool gain functions, and it’s all modular. I use that a lot when mixing to run things through, especially drums, like sends, when you want to keep the bite and the low end but you can kind of carve out EQs in a different way. I have a Shadow Hills preamp, I’ve got the Chandler RS124 compressor and Focusrite Red preamp. And I just ordered a Binson Echorec 3, which I’m very excited about. That’s my whole home rig. It’s really built for mixing. I record a lot of projects that I’ve done the basics for in my home studio and then take them somewhere to do live drums and things like that.

Where do you like to record?

I use three studios a lot. I use these two engineers all the time, David Spreng and

Mark Rains.

There’s a studio in Echo Park called

Station House. The Duff McKagan record, the White Buffalo record, the Jamie Wyatt

At Sunset Sound, from left, Brandi Carlile, Tanya Tucker and Shooter Jennings.

record and the Hellbound Glory record were all recorded at Station House. And Mark engineered the Tanya Tucker record. I’ve recorded probably 20 records in that place.

The American Aquarium record was cut with David Spreng at Dave’s Room, which was Dave Bianca’s old studio. David Spreng’s studio is deep in the Valley; it’s a little larger, so it’s got more hang room and isolation. It’s got tons of amps and gear and an amazing rack, everything is prewired, it’s all top-of-the-line.

Then, Sunset Sound, if the budget is there, it’s my preferred place. I did Tanya’s record there and a record for The Mastersons there in the Purple Rain room.

Looking back, when did you first become aware of the recording side of music? Well, my dad, when I was very little, he would go in the studio; I loved being there. I remember very early memories of Chips Moman’s studio on the east side of Nashville; he had an arcade and a poker machine, and I remember going there at night thinking this was the coolest place I had ever seen.

When I was 13 or 14, I got into Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral and was so blown away that this one dude had done all of that. I was a computer nerd from a very young age. I played drums first, and then piano. Guitar was last, kind of out of necessity. I’m still not a great guitar player. But I realized, hey, I can play keyboards and I can run a computer and do all that. So I got this software, Studio Vision Pro, and it was what Trent Reznor used.

I would save up money as I got a little older. I would go to Sam’s Music in Nashville and buy little drum machine brains, and I had a cool Korg keyboard that one of my dad’s keyboard players wasn’t using anymore. So I started piecing a home studio together and put together a band. I would program all the instruments and I had two guys who played guitar.

My parents had put together a college fund, but I was like, “I would rather not go to college and [instead] get a starter Pro Tools kit.” I spent two years messing with that and recording a lot. And then I was like, I’m moving to L.A., I’m going to be in a band and I’m gonna bring all this shit with me.

It wasn’t until I met Dave Cobb that I started recording again; he flipped me back into that world and became somebody who taught me a lot about gear.

When did you start making records for other people? That was really a natural progression that started when Dave Cobb moved to Nashville, around 2010 or 2011. I produced Marilyn records, I produced a record with Jason Baldwin and a band called Fifth on the Floor. I did records with a couple of other bands along the way and started getting my own legs.

Once I got to a place where people wanted me to do their records, I realized that, as an artist, I only got to do a record a year, maybe two in three years. To do a record every month for a different artist, to jump into someone else’s band and their concept, apply it through my lens and then jump to another one, it became very apparent that this is what I enjoy the most. I love my own stuff, but playing on the road and doing shows, that’s just time that I can’t be in the studio and be making up new stuff.

It’s interesting when those lines blur. When you’re playing on records that you produce, do you feel like you’re moving in and out of a producer role? When they happen, they’re as important as anything I’ve ever done as an artist. When you work with people, you bring the A riffs and the A ideas all of the time, and it doesn’t live in the same house in the same way, the artist side and the producer side.

But I’m using the same brain. It’s fulfilling to do a record like American Aquarium’s where I didn’t play anything on it and was just behind the console, or one with Brandi Carlile when I’m playing piano the whole time, or with Marilyn Manson where I’m writing all of the music. They all become my favorite project in the moment. And they all become like The NeverEnding Story: In that movie, this kid goes into the bookstore and the dude’s got a book and says, “This book is not safe, you can’t be this book.” I feel like that guy, like that’s my role.

I’m so glad you brought up The NeverEnding Story . I heard that you and Brandi Carlile bonded over that movie. I love that movie! We still connect over that. I asked her to sing that theme song on the Giorgio Moroder tribute album. Right after that, she asked me to do By The Way, I Forgive You with Dave Cobb. Then about a year later Manson came, then Duff came, and Tanya came and Jamie and Hellbound Glory, and White Buffalo, they all just rolled in at once.

By The Way, I Forgive You was such a watershed moment. Did things change after that?

Producer Shooter Jennings behind the board at Station House studios. Always a producer and musician, Shooter Jennings with artist Jaime Wyatt in the control room at Station House studios.

Yes, but not immediately. It wasn’t until about halfway through the year that people started paying attention to it. But when the Grammy thing happened, it was feeling like being in training for something for your whole life, then something happens and it’s like, “Are you ready?” I’m like, “Yes, I’ll try to be ready.” And Chariots of Fire is blazing in the background.

While I’m Living is Tanya Tucker’s first album in 17 years. How did you know the time was right, and how did you help her overcome her reluctance to record? Well, a lot of things happened in the process. The Brandi record came out in the beginning of 2018, and I had produced the Pinball record for Hellbound Glory, a band that I love and is on my label. Hellbound did “Delta Dawn” on their record, and a friend had an idea that we should

do a seven-inch for Record Store Day that on one side has Hellbound Glory doing “Delta Dawn” and then get Tanya Tucker to do one of their songs called “You Better Hope You Die Young” on the B-side. I knew my mom and Tanya were in touch recently, so I reached out and I got Tanya to do it, with some reluctance.

She was so cool, and I was just blown away by the power of her voice. A couple of days later, she was leaving, and I said, “I would love to produce a whole record for you.”

What was her reaction? She said yes; I don’t think she thought much of it. A couple of days later, I flew to New York to play with Brandi on Colbert. When I got there, two things happened: In the hallway going up to soundcheck, Greg Nagel, who runs LCS, Brandi’s label, says, “Duff McKagan’s got a new record, would you be interested in producing it?”

Then I went to the stage and Brandi was there, and I said, “Hey, I just recorded Tanya Tucker; she sounds awesome,” and she was like, “OMG! I love her!” I told her, “You should do it with me!” Immediately, Brandi and I started cooking up this thing without Tanya being involved yet, even though she knew I wanted it to happen.

So I wrote her and told her about Brandi; she didn’t even know who Brandi was. Brandi and I were over here, cooking up this vision for the record; Tanya and The Twins, her writing collective, were writing songs. I was picking songs and finding old songs, and we kept trying to present it to Tanya and we couldn’t even get

it to her. We had to get a CD physically to her, and then she said, “I don’t like them, I don’t think they’re good.”

We were supposed to record on January 7, 2019, and on Christmas Eve Tanya called and told me she didn’t think it was going to happen. She was halfway to L.A., but luckily her bus driver was sick or had a gig, and my bus driver happened to be driving for her. So I write to my bus driver and tell him, “If she turns the bus around, you tell me right away so I can at least call her and stop this from happening.”

It kind of sounds like you kidnapped her. A little! The night before, she came to my house and had a drink, and I said, “Please, just trust me. If you hate it, you can just throw it away.” The next day she met Brandi, and even in the studio she didn’t know what was going to come out of it. I think she didn’t have both feet in it all the way. That’s when we thought, “Let’s go ahead and mix it, and we’re going to play it for her in front of a small group of people so she could see their reaction.”

We immediately mixed the record with Trina Shoemaker, who is an amazing mixer. We played that for Tanya in front of label people. When we did that, that was when she got it. That was Brandi’s idea, and it was brilliant because it showed her how other people would react when they heard it, and it got her to finally understand that she had done something really good.

Also, this was the first record she had done since her father had died; he was always at the helm of her career. So when we did this, we were validating her and honing this record in with a lot of care.

It seems like you connect with artists who want to express themselves in a vulnerable or confessional way, or who want to make an album with a social conscience. What do you think is behind that? I don’t know, maybe it’s that the type of friendships that I’ve made have been with people that have something to say. I care about social issues, but I think it tends to be that I live in my childhood a little bit, and there’s some honesty about that. I’m attracted to people who share that. All of them are people who felt that the sky is the limit, and I’m that way, too.

Do you feel like fans are more open today to nontraditional sounds in country or rock? Is it easier to get them to follow along when you make, say, a Giorgio Moroder tribute record? Yes, there were times, like the Moroder record and also my Black Ribbons record, that when I did it, they were not ready. I’m not saying this to toot my own horn, but Black Ribbons was definitely Dave Cobb’s and my creation. Then you look 10 years down the line and Sturgill did the Sound and Fury thing; that definitely helped people get in the mindset for things like that.

I feel we were alone doing it. Just like Hank III was alone crossing metal and country and the satanic thing. Nobody was ready for that. But when he did, it led to bands and artists really expanding the concept of country.

Look at when David Bowie did Ziggy Stardust, or even weirder, like he popped in China Girl the way he did, or like on [Iggy Pop’s] The Idiot, which Bowie produced. That stuff was out there at the time, and now people knock that stuff all the time, and say, “That was inspirational.” People like Pink Floyd, they redefined the boundaries of what music was. They were inspired by Syd Barrett, who was their predecessor. Guys like my dad, people said, “That’s really traditional country,” but when he came out, that was way rock for country. Did he talk about his rock inspirations? My dad was obsessed with Buddy Holly, who had guided and mentored him. He was so into the sound of the drums, and blending that in country music. Richie Albright, who was his drummer, kind of invented that style of drumming for country. The two of them invented the sound that became the sound of country in the ’70s, and now people knock that sound like that’s old, traditional outlaw country. That was not traditional, that was way out of the box and created a new view for people.

I want to end with a quote from Brandi Carlile. She said, “I knew I wanted to work with Shooter the first time we discussed our hopes that our generation and peers would turn their heels on the dangers of disappearing down a path of retro-mania. Shooter knows that right now matters, that this moment is profound enough. What would Woody Guthrie say now? He’d probably look and sound a lot like Shooter Jennings.” That’s a very kind quote. I know what she means: She read an article where I was just spouting off, where I was saying that you run into these country artists who are dressing like it’s 1967, they’re dressing like gunslingers with long beards, and I’m like, “You were playing Pokémon six years ago!” That was my whole point: Being true to who you are is very hard to do, especially when you’re trying to create something. But, if you can do it, well, it’s the most unique thing you can do.

It’s a long game, it’s not a short game. That long game, it’s going to come out that people are changed by you because you said, “It’s okay to be me.” Because at the end of the day, we don’t have to be anybody but ourselves around each other. When we make music, it’s the same way, you know what I mean? ■

PMC Studios

WE’VE GOT THE PROSCOVERED. PRO look. PRO build. PRO results.

FREE ACOUSTIC ADVICE

GET HELP WITH ROOM SETUP

ORDER DIRECT

(404) 492-8364 GIKACOUSTICS.COM

“The wide selection of colours, sizes and modularity of their panels were a major factor in our decision to use GIK products.”

LUCA BARASSI, ABBEY ROAD INSTITUTE

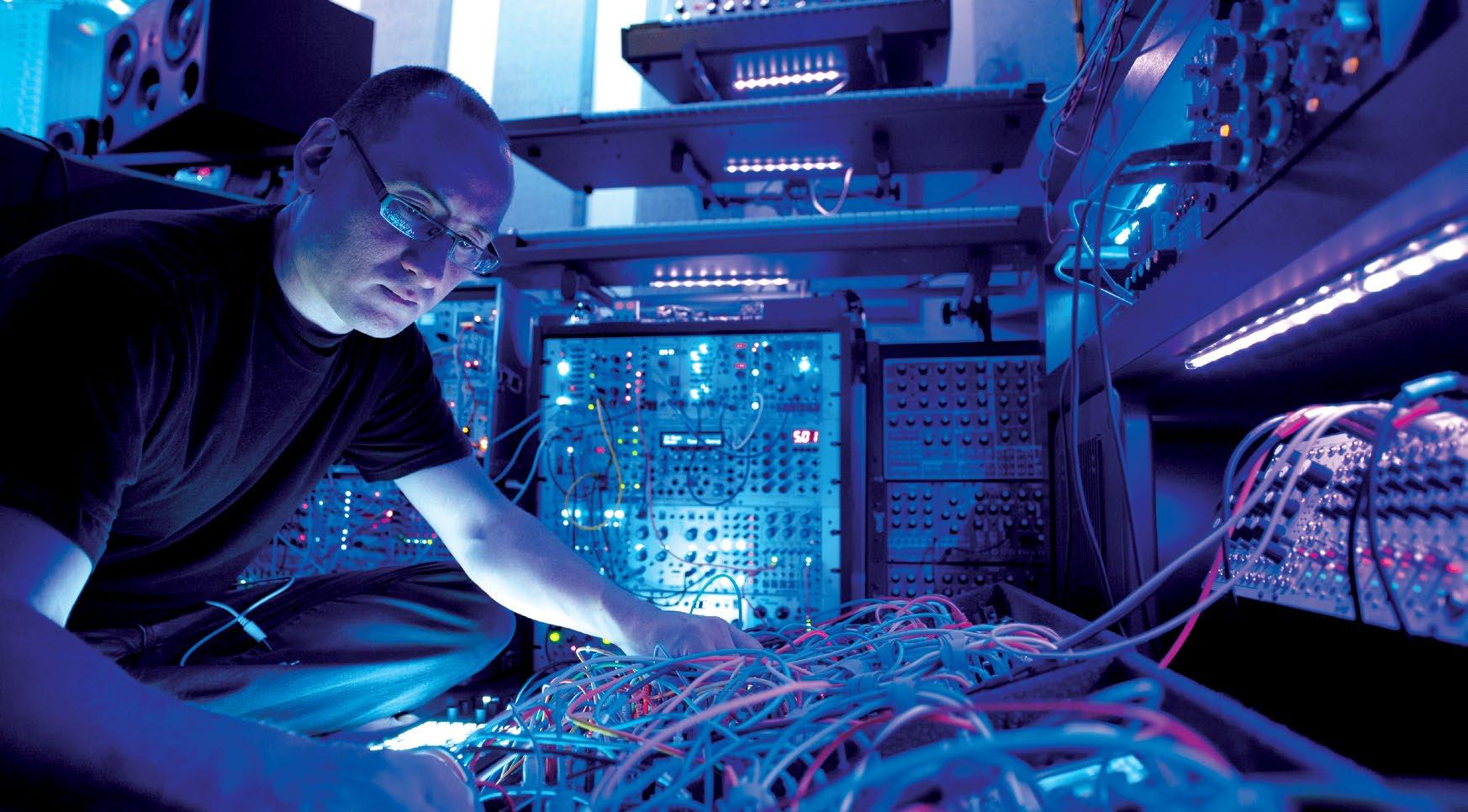

Richard Devine The Art of Manipulating Machines in a Modular World

By Sarah Jones

Richard Devine is in his element when he’s on the edge. For more than 20 years, the musician, producer and sound designer has stretched the ever-elastic boundaries of electronic music, releasing eight albums on Warp, Planet-mu, and Schematic Records, remixing the likes of Aphex Twin and Mike Patton, coding FFTs in Max/MSP and SuperCollider in his downtime.

He contributed to the Doom 4 soundtrack, programmed sounds for Trent Reznor, and developed patches for Native Instruments, Moog and Korg. But Devine’s imprint goes far beyond music: He’s created soundscapes for apps, gaming platforms, and user interfaces for electronic devices, and he’s done sound design work for Nike, Coca-Cola, Lexus, HBO, Nestle and McDonald’s. When he’s not in his Atlanta studio, Devine is often on the West Coast developing immersive sound environments for tech giants like Google Apple, Sony, and Microsoft.

That’s by day. At night, he reconnects with his own music, which lately focuses on the unpredictability and immediacy of modular synthesis, machine learning and generative composition. It’s a literal “hands on” approach that defined his most recent album, Sort\Lave (Timesig), a mutating collage of glitchy rhythms and richly textured soundscapes, crafted on a mountain of carefully curated Eurorack modules.

The last time we talked, you were finishing up Sort\Lave. You said you wanted to get back to analog and you were sculpting things by hand, never touching a mouse.

I did. I mixed Sort\Lave entirely using outboard analog compressors, EQs, pretty much everything that I would normally use as plug-ins; I just decided, “I’m going to go ahead and do everything with hardware just to see what happens.” It would have been easier in the computer because you have ability to use instant recall, obviously. But for this record I wanted to do everything with my hands and my ears and not really be thinking about music in terms of interacting with a timeline and a screen with the mouse and a computer keyboard. In my humble opinion, I feel like this is my best recording to date because it’s completely mixed with analog hardware.

This record didn’t use any samplers at all. Every hi-hat, percussion sound or synth sound was generated with multiple modular systems chained together, sharing the same clock and tempo. I have gone full circle, as I originally started making music with analog synthesizers in the early ’90s.

When did you decide you wanted to take a new approach?

About two years ago I decided to take a few hours every single night after putting the kids to bed to focus on creating patches and music. I’d catalog and record, set up my systems here at the

Richard Devine in Studio A of his modular synth-based production facility.

PHOTO: Austin Donohue

studio, and write a piece of music. I was trying to develop a system that would allow me to write very quickly so I could come up the ideas really fast, or have things set up where I could have some spontaneity; something could accidentally happen that sparks a whole entire composition, so I could drive the rhythmic sequences, the melodies, some of the sound effects, some of the textures and timbres very quickly.

For about eight months I was figuring out which modules I was going to use for all of the rhythmic sequencing. I wanted to be able to program the data of the rhythmic sequences, and then take that data and repurpose it and play around with it live. Then I could run it through probability-based filters where I could either remove bits of that data or add other bits of data in real time. With all of these stored sequences, I could then alter them and mutate them, or do other strange things to generate new musical ideas.

Are you applying these processes to other projects?

For my new album that I’m working on now, I’m going back into the computer again. I want to use the computer to explore machine-learning based applications. I’m really interested in this idea of developing a machine-learning algorithm that learns things that you like to do, like sequencing in certain time signatures or at certain tempos, and then gives you different outcomes.

I was inspired by the work of David Cope,

an American author, composer, scientist and former professor of music at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His primary area of research involves artificial intelligence and music; he writes programs and algorithms that can analyze existing music and create new compositions in the style of the original input music. I was able to get hold of his books The Algorithmic Composer and Experiments in Musical Intelligence; in them, he discusses basic principles of analysis, pattern matching, object orientation and natural language process. Experiments in Musical Intelligence includes a CD-ROM that contains the documentation for the program SARA, Simple Analytic Recombinant Algorithm, which produces new compositions in the style of the music in its database.

David’s work has been around since the early ’90s, so this idea is nothing new, but it’s an interesting area to explore; not many people have tried utilizing this approach much with modern music. I think it will be interesting to create an algorithm that you can reward if it outputs something that you like, and then it stores all of these data streams of music in a database. Think of these music data streams as sounds, gestures, and sequences or arrangements and patterns. Then you can pull bits and pieces from that database to create entirely new compositions.

Wow, that’s pretty wild. We haven’t even dug into your rig.

Well, for this last album I was mainly focusing on using analog outboard gear for the mixing and

mastering. A funny thing happened with a few pieces of hardware, like the Manley Vari-Mu and Massive Passive. I actually opened up the Universal Audio plug-in versions, and I would re-create the preset setting and then print out recall sheets. Those would be my presets for the real hardware. I did that with the API 2500 Bus Compressor and the Bax EQ. All of my settings, I could recall for each song. I also did that with the Pultec EQs and my API 550b EQ. It made things really fun. Now there is a much better solution called PatchRat App, which is a studio management app for iPad that can map out your entire signal chain, plus it has a huge database of recall interfaces for almost every manufacturer.

Luckily, all the gear that I have here in hardware, I also have as plug-ins. I could reference back and forth, but also recall things very quickly. I wanted a record that had infinite detail but was also engulfed in this beautiful, warm analog, giant,

Richard Devine’s nest of cabling and connections, which he calls his modular station.

thick field of sound.

I realized that you just get so much more depth and weight using the analog stuff than you do with plug-ins. I use this box called the HG-2 by Black Box that uses custom input transformers to feed two paths: The main signal path travels through a 6U8A pentode tube stage that drives into the triode stage that follows, resulting in everything from subtle harmonics to full-on saturation. I ended up using it every single track, and it just really brings things to life.

How did taking this approach inform your mixing process?

I think that by going more simple, I made the mixing process a lot easier. Usually when I would do stuff in the computer I’d have like 64 tracks and just crazy amounts of stuff happening. For this record, I really stripped things down. On average there are 16 to 24 tracks, and I was using Dangerous Music 2-Bus+ and 2-Bus LT analog summing mixers; I wasn’t even using a console. The only role the computer played was the end capture device. To capture material on the way in, I used two nw2s::o16 Eurorack modules; the ::o16 is a 16-channel, balanced line driver interface with 6dB of gain reduction in just a 10hp module. I would then go from the ::o16s into two Universal Audio Apollo 16s. From there I’d take all of the stems and mix them back through the Dangerous Music system.

Devine at work, from floor to ceiling.

PHOTO: Merlin Ettore

Would you say you’re inviting chaos into your work?

Yeah, I have always been a fan of using randomness, chaos, and probability in my work. I would

Devine regularly performs live, putting into practice the spontaneous workflow he develops in the studio.

love to explore using the computer for analyzing musical data, and then using machine learning, AI-driven algorithms, then somehow integrating that with my modular systems, integrating the two worlds and see what happens; see if I can get that spontaneity of the instant sort, of the physical interaction you get with the modular. That’s the one thing that the computer has difficulty doing; you just don’t have that immediate feedback that you get when you’re working with a piece of hardware like a real physical instrument.

With a computer you can get similar outcomes by playing samples and things, but the modular gives you so much more. You’re making music with just electricity and control voltages that fluctuate and move around between these cables. It’s such a fascinating way to make music with one of the rawest elements. With a modular system it will never, ever play the same way twice, no matter how many times you perform the patch. There are so many variables that can shift the patch in any direction, like the temperature of the room, drifting of analog

oscillators, unstable circuits. It’s like working with a living organism that is constantly moving and mutating. There are thousands of interactions in the little environment of nested cables that you’ve created. One knob twist can shift the whole thing in a completely different direction, and I love that. You just ride this super-fine line of losing it all.

You’ve been exploring modulars since you were a kid; how did those early experiments inform the way you work now?

I’ve been using these systems since high school. The first modular system I had was the ARP 2600. My 2600 was a Version 1.0 from 1971 with the 3604P keyboard; I bought it from a local pawn shop. I was buying a lot of the early portable modular systems that were made in the ’60s and ’70s, like the EML 101 and the EMS Synthi from England. On my early records I used a lot of the esoteric smaller, portable, semimodular systems available at the time. These are the machines I learned to patch and make music on in the early ’90s.

I knew that format going into the modernday Eurorack modular synthesizers, which have become hugely popular over the past five to seven years. I was right at the beginning with that. Eight or nine years ago I started buying and building up two starter systems by Dieter Doepfer, a German Eurorack manufacturer.

When you’re working with modular synths, unpredictability is the name of the game. Does AI bring a different sort of unpredictability?

What’s interesting about modular is, you’ll come up with really cool stuff, but then you lose it. Even if you take patch notes and get everything perfectly, you’d still never get it exactly right. There are so many variables in putting together large, complex patches, like when I was writing the album.

I wanted a machine-learning algorithm that would be able to analyze and record some of these things that would happen so I could recall and reuse that data and put it back into the modular systems. Otherwise, it would be gone forever as soon as I pulled the patch cables. I now have modules that can play back exactly millisecondper-millisecond if I want to. You could do it with harmonies, too.

What do you want to manipulate through machine learning?

I want to develop an engine that can analyze every component of what I create spontaneously here with my system, and then take that data, repurpose it to create more music, and then improve that data, and even mutate it to generate other springboards of ideas. Then it’d just keep building from there.

It took me almost a year to develop the system to where I can almost compose in real time, set up a couple of variables, set up a couple of modules, start patching, and things start happening. Then I’m composing, and I’m writing in real time and performing; I’m creating a track on the fly.

I’ve been experimenting with Max/MSP Version 8. During my visits to Google headquarters, I was introduced to Doug Eck, a principal scientist at Google working on Magenta, which is a research project exploring the role of machine learning in the process of creating art and music. Doug’s focus is developing new deep-learning and reinforcement-learning algorithms for generating songs, images, drawings and other materials.

Doug has inspired me to think about how I could use AI to help me to take ideas, reincarnate them, and then feed them back into my system. Then tripping the algorithms, in a way, just seeing what happens if I skew things or feed it all this nonsense, and then mix it up with all these things that I like. What kind of music would it create; what would I create, with all my favorite stuff jumbled up in this soup of craziness?

Do you find that you’re shifting between macro and micro perspectives a lot? Do you have to let go of certain preconceived notions?

Yeah, exactly. That’s the whole reason I got into creating music on the modular again—the idea that you might be able to get what you have in your head 100 percent, and you might not get it at all. Like you said, you can work it in micro levels, these infinite, crazy little microscopic worlds of sound. Usually with the computer I can get 90 percent of what I have in my head, but that’s kind of boring. There are no variables that will shift you off course. There’s no random, spontaneous thing that’ll explode right in front of you and make you go, “Oh, I didn’t even think to do that.”

For all of this complexity, that concept of letting go is a lot like live recording, the days before multitrack, that feeling of, “This is what I have, and I’m going to get some happy accidents and go with it.”

That’s totally it. We got so far away from that with digital recording. Sure, with bands, you’re trying to get the perfect take, but you don’t get that random spontaneity that you do with the modular system. I just don’t know any other instrument in the world—and I have a lot of strange ones that I’ve collected all over the world—that has that feedback. You’re basically creating this environment. You decide the rules of

Richard Devine’s synth corner. how that environment is going to react, and then you’re steering this ship of chaos and it becomes alive. It’s like an electrical organism that’s moving in the wires for this one moment in time. You have to record this crazy, alien creature that’s living in these cables before it’s gone.

How do you apply these processes to sound design?

I use the modulars for creating layers very quickly. They generate lots of great textures that help me with sound design, especially with gestures, like low-impact sounds. My sound effects get used in games and trailers, so a lot of risers, tensionbuilders, things that create unsettling feelings, the modular is just perfect for that because it can create such alien, strange sounds and timbres. You can work with custom tunings, and scales. Everything is just completely organic, raw, and hands on.

I use a lot of plug-ins and other pieces of digital effects units. I’m not a purist in any way when it comes to my sound design. I use any sort of microphone: Ambisonic, binaural, stereo, mono, it doesn’t matter. Or any kind of mic preamp, recorder, or instrument. There is no right or

wrong way to go about. I will use tanker truck for my percussion sounds or the lid of a garbage can for a snare drum.

Are you incorporating machine learning into shows?

Not yet. I won't be getting into that until later in the year. Right now I'm recording and developing the system that'll analyze what I'll do. Then it’ll be figuring out how I'll synchronize everything to take all that data and feed it back into my system here.. ■

Sarah Jones is a writer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She’s a regular contributor to Mix, Live Design, and grammy.com.

Resurrection of a Console Danny White, Geoff Frost and the Legend of Sound Techniques

By Steve Harvey

What significant piece of audio equipment is common to “Hey, Jude,” several tracks off the White Album and a slew of career-defining LPs from the likes of David Bowie, Queen, Elton John, The Doors, Deep Purple, Genesis, The Rolling Stones and Nick Drake?

While you think about that, let me tell you a story.

In late 1964, Geoff Frost and John Wood, two staff engineers working at Levy's Sound Studio in London, decided to quit and open their own recording studio after the giant U.S. label CBS acquired the company. Both still in their 20s, they scraped together what money they could, found a space in a former 19th-century dairy near King’s Road in Chelsea and got to work. Having only a limited budget, they spent wisely, buying various high-end mics and outboard processors, but electing to build much of the rest, including the electronics for the Ampex tape decks they had acquired and a mixing console of their own design. That console, which they named the A Range, is what ties together those tracks by The Beatles and albums such as Hunky Dory, Sheer Heart Attack, Madman Across the Water, Morrison Hotel, Fireball, Nursery Cryme and so many others, which were all tracked or mixed, or both, through the desk.

Of course, you say, the Trident A Range. Well, no, not that A Range.

A STUDIO AND A CONSOLE The sonic character of the recordings produced through the late ‘60s at Frost and Wood’s studio, which they named Sound Techniques, earned such a reputation that other London studios began clamoring for their own A Range desks. Frost set up a workshop upstairs and began to hand-build custom consoles for the likes of De Lane Lea Kingsway and Trident Studios, while Wood ran the studio below. When the red light went on in the workshop Frost and crew would set down tools until the end of the take.

It wasn’t long before Tutti Camarata at Sunset Sound Recorders in Hollywood heard about the Sound Techniques A Range and ordered one to enable his facility to work in the new 8-track format. Installed in April 1967, the desk was the first British-designed mixing desk ever sold in the U.S., according to an August 1968 article in International Broadcast Engineer magazine. Jac Holzman ordered the second U.S.-bound Sound Techniques A Range for Elektra Sound Recorders in West Hollywood in 1968.

Elektra’s desk was almost identical to Trident’s, which was installed around the same time. But several years later, rather than buy a third Sound Techniques A Range, Trident Studios—where some of those classic tracks and albums were produced—decided to build their own console. Confusingly, they also called it the A Range.

Later, Sound Techniques also introduced a simpler desk, the System 12, which they manufactured in Mildenhall, England. The desk was a particular hit with reggae studios in Jamaica. The Rolling Stones bought one for Kingston’s Dynamic Sounds Studio for their Goats Head Soup sessions; Paul Simon also used it to record “Mother and Child Reunion.” The famed Kingston facility Randy’s Studio 17 also installed a System 12.

Sound Techniques’ studio and manufacturing ceased operations in 1974 after the Chelsea building lease ran out. Olympic Studios acquired

Above: Detail of the famed Ernst Turner meters, incorporated into the new Sound Techniques ZR console.

the facility, running it until the early ‘80s. In all, Sound Techniques built just over a dozen A Range consoles. No complete functioning desks still exist, but two were broken down, and the input modules can still be found here and there.

The upshot is that the Sound Techniques name has largely been forgotten. Indeed, engineer and producer Ken Scott, who worked with The Beatles, Bowie and so many others on the desk, told an interviewer a couple of years ago, “The most amazing array of albums were done through a Sound Techniques board, and no one knows it.”

Left: The beautiful new Sound Techniques console installed at Tweed Recording Audio Production School in Athens, Ga., in late 2019.

PHOTO: Courtesy of Danny White

Above: The original Sound Techniques console at Elektra Sound Recorders, West Hollywood. It was the second purchased by a U.S. studio.

Well, now the Sound Techniques mixing console is back in production, and not as a 500 Series module or a 19-inch rack unit— although the latter is also being manufactured— but as a custom-built desk, known as the ZR. The modern-day reproduction incorporates updated electronics that improve the operational efficiency, maintenance and product longevity while faithfully replicating the sonic characteristics of the original.

What’s more, says Danny White, who acquired the company with his partners in 2015, “It looks very much like the original desks that would have been built in the 1960s.” The aesthetic similarity is due in no small part to the desk’s classic Painton quadrant faders and Ernst Turner meters; the company acquired both brands and is remanufacturing the components.

THE NEW-VINTAGE SOUND TECHNIQUES White, who has established Sound Techniques about 75 miles south of Los Angeles, was once a touring musician with a studio—Formula One, featuring one of Trident Studios’ Trident A Range desks—in Phoenix, Ariz. He later owned and operated 16 Ton Studio on Nashville’s Music Row, home to RCA B’s famed 1971 API and the prototype Dymaxion console, built in collaboration with Steve Firlotte and Ian Gardiner, now partners in Tree Audio.

“My passion behind Sound Techniques revolves around the magic that the English were able to create in the 1960s and ‘70s,” says White. Seeing the writing on the wall for Music Row as developers started moving in, White was getting ready to leave town when he heard that Frost was selling a recording console. “That turned into him wanting to sell the company and have it with a person who would rebuild it and bring it back,” he recalls. “Geoff and I got together in late 2014, and we ended up buying the company. Everything was in a 17th-century carriage house on Geoff’s estate in Norwich, England. We had a great week together, packed it into a shipping container, put it on a boat in Liverpool and shipped it through the Panama Canal to Long Beach in California. We had the original designs and blueprints and tons of company history. We had all we needed, including the original input and output transformers, to rebuild the Sound Techniques module the way it was.”

White has designed the chassis and mechanical components of the new Sound Techniques ZR and builds the consoles in California. “But the design of this console, with regard to the electronics, is 100 percent English; we stayed true to the English heritage and to the original design,” he says.

To that end, White enlisted veteran audio electronics designers Gareth Connor—with whom he had previously worked, restoring the Manor Mobile Helios board—and Graham Milnes, who set up the Sound Techniques Skunk Works at their homes in the north of England. Connor and Milnes each have decades of experience in audio product development, working for Soundcraft, Focusrite, AMS Neve, Calrec Audio and through their own companies. Additionally, Neil McCombie, whose background includes 25 years with Soundtracs and AMS Neve and as an independent contractor, has brought his technical services expertise to bear on the new venture.

Basically, the ZR is an 8-bus, inline monitoring console with fader swap, six mono aux sends, two foldback sends with pan and eight mono/four stereo groups. But the crux of the classic Sound

Techniques character is in the input module, specifically the transformer-balanced, variable impedance microphone amplifier, inductorbased EQ (thoughtfully expanded beyond the limited original A Range design to meet modern expectations) and the dual class A transformer drive. Beyond those fundamentals, choices such as input channel count, metalwork finish, wood trim, automation and other options, including a fully customized or even remote center section, can be supplied to order.

THE GUTS OF A DESK Connor started working on the ZR circuit design in early 2018, calling in Milnes for his inductor and transformer knowledge. “There’s nothing like having a close friend and really top designer having an extra eye over what has already been done,” says Connor. “Without Graham’s involvement, the console would not be as good as it is.”

One of Milnes’ first tasks was to reverse engineer and replicate the Sound Techniques console’s original transformers. “We ascertained that the core material of the output transformer was 50 percent nickel laminate, and we found the gauge of the wire,” says Milnes. “We were able to ascertain all the parameters—the turns ratios, impedances, gain through the transformer— from the original transformers. And by doing comparative tests between the old and the new we got virtually identical results; we were very pleased with that.”

Like the original desk’s channel strip, the new ZR has a nine-position switch for matching input impedance through a combination of 1.5k-, 600- or 60-ohm transformer tap selections, each with three level settings: 7 dB or 15 dB of attenuation, or out of circuit. “It’s quite unique,” says Milnes. “And it’s 100 percent original.”

The input transformer is followed by a discrete amplifier with a line output transformer, a circuit known as the 3035 in Frost’s original design. “The transformer was a faithful reproduction,” says Milnes. “The line transformers have dual primaries, so it’s a class A, discrete, dual-drive circuit.” The original circuit has been slightly tweaked to balance up the power supply requirements and improve the input headroom, he adds.

There is one 3035 between the input and the equalizer section and another following the EQ, both feeding an insert point. “To keep the essence of the original product we chose to leave the transformers in circuit all the time, even if

Above: This photo of Frank Zappa at Sunset Sound Recorders in 1969, at the first Sound Techniques console in the U.S., originally appeared on the front page of the Arts section of the L.A. Times.

“We were able to ascertain all the parameters from the original transformers. And by doing comparative tests between the old and the new we got virtually identical results; we were very pleased with that." — Graham Milnes

the insert is switched out,” says Milnes.

The original Sound Techniques inductor-based EQ was somewhat limited, with no highpass or lowpass filters, nor a mid-frequency section. In consultation with engineer/producers Ken Scott and Dave Cobb, the team have brought the ZR section up to date for modern day users while using the same passive, inductor-based topology.

The LF section originally offered an 80Hz shelf or a 150Hz bell response. Milnes retained the historically well-liked 80Hz shelving frequency and added 30, 50, 90, 160 and 270 Hz bell response selections. “From experience and feedback, we settled on a Q value of 1.8 on the bell,” he says.

The original Sound Techniques HF section gives a very high-Q bell response on the boost with a separate capacitor-based cut circuit offering a shelving response. Milnes has reengineered the circuit so that the Q broadens more subtly than the original as the selected frequency increases. “You have individual frequency selections for the boost and for the cut. It’s like having two bands, one doing boost only and one doing cut only. You can apply them simultaneously and get some interesting response curves,” he says. With such a flexible HF circuit available, a lowpass filter was deemed unnecessary, but Milnes added a highpass filter selectable to 40 Hz, 80 Hz or 120 Hz.

There was no original MF section to copy. “That’s entirely of my own development,” says Milnes, who designed a circuit with separate low- and high-mid controls. “It’s inductor-based; I’ve used a series resonant topology.” High-mid covers the 900 Hz through 8 kHz range while low-mid extends from 200 Hz through 1.6 kHz. Both offer ±12 dB cut and boost.

The circuitry that follows the input and EQ sections is all modern-day, high-spec operational amplifiers and surface-mount components, reports Milnes. “So it’s wide bandwidth, ultralow noise and ultra-low distortion. In other words, it’s as neutral as it can possibly be and shouldn’t significantly add any coloration—and I think that was what we managed to achieve.”

One useful facility not often seen in music consoles, says Connor, is that the mix bus outputs, specifically the stereo mix and groups and the echo and foldback sends, simultaneously offer both an electronically balanced and a transformer balanced (via the 3035 dual class A amp) output. “This is good news for engineers

Danny White, co-owner of the new Sound Techniques and designer of the chassis and mechanical components.

Above: Geoff Frost, founder and owner of Sound Techniques Ltd., was the designer of the original Sound Techniques A Range console.

The brand-new, just-off-the-line ZR16 console.

who like iron in their outputs,” he says.

Because all of the controls are stepped, notes Milnes, “If you take a photo of the surface you can clearly see the settings, so you can get repeatability if you wish. It’s very quick to set up.”

STILL BUILT BY HAND The original Sound Techniques A Range desks were all hand-built by Frost and his helpers with point-to-point wiring. Five-and-a-half decades later, Connor and Milnes have been able to leverage modern design and manufacturing techniques and components that make the new ZR a service person’s dream.

This is where the third member of the electronics team, Neil McCombie, who maintains the consoles at Mark Knopfler’s British Grove facility, has provided design recommendations. “Neil’s input has been most useful in regard to what a service engineer would like to see or expect to see,” says Connor.

Circuits common across the console, such as balanced inputs, electronically balanced outputs and mix amps, are grouped together in blocks of eight paths on plug-in cards, Connor explains. Thus, complex systems can be created efficiently, with the advantage that much of the signal path comprises PCBs with dependable performance parameters.

“Rather than having expensive, complete spares on the shelf you can have a handful of small circuit boards, like the equalizer,” says Milnes. “If you develop a fault, even someone non-technical could change that out. You don’t even need a screwdriver.”

The modular construction also allows for consoles to be manufactured with a remote master section. “You have the master fader and

controls in what we call the RMS, the remote master section, so you bypass the expense of a center section,” says White. “We’ve already done that. It works very well with a DAW, and a significant amount of money can be saved.”

Sound Techniques has also introduced two 19-inch rack units based on ZR circuitry. The first is the ZR7064CS channel strip, which offers the mic pre and EQ from the console, including the Z-Match impedance and level selector, in a 2U box. “The two-rack unit compressor is coming this summer,” White says. “We’ve already got the compressor/limiter module for the console, so we’ll just pull it out and plug it into a rack, old-school, like an old PYE or EMI compressor.”

As White says, Sound Techniques ZR consoles are already rolling off the line. Indeed, anyone who attended the 2018 NAMM Show likely noticed the enormous 48-input example on display, which Ken Scott demonstrated with a mixing master class featuring several classic Bowie tracks. That console, which is configured for 5.1 work, is now at the Tweed Recording Audio Production School in Athens, Ga., shortened to 32 inputs to fit the space, along with several 8-input sidecars.

Examples of the new Sound Techniques ZR in action can already be heard, too. For example, Bruce Botnick used a ZR sidecar while working on the 50th anniversary reissue of The Doors’ 1969 album The Soft Parade, which he originally recorded at Elektra. Bob Rock also used a ZR for parts of The Offspring’s upcoming record. And Dave Cobb tracked a large part of John Prine’s Grammy-nominated The Tree of Forgiveness through a ZR sidecar. n

Supercharged MIDI 2.0

Promise of Vast Improvements... But It Might Take Awhile

Craig Anderton addresses the MIDI 2.0 panel at NAMM 2020. (Left to right), Athan Billias (Yamaha), Rick Cohen (Qubic), Phil Burk (Google), Pete Brown (Microsoft), Jean-Baptiste Thiebaut (Ableton), Lawrence Levine (Horn).

By Mike Levine

With all that has been going on around the world these past six months, audio professionals will be forgiven if it slipped by that back in January 2020, at NAMM, the MIDI 2.0 spec was introduced, bringing with it the promise of significantly more powerful and expressive functionality. In a small way, this is a very big deal, as the new standard is finally real after years in development. At the same time, it doesn’t mean there will be a flood of MIDI 2.0 keyboards available for the holidays. Big deals take time.

Good-old MIDI 1.0, which has remained surprisingly relevant for 37 years, isn’t going away anytime soon. Even when manufacturers and software developers start to put out MIDI 2.0 products on a regular basis, there will still be a massive base of MIDI 1.0 products out there that musicians won’t want to cast aside.

Fortunately, one of the main pillars of the MIDI 2.0 project was to maintain backwardcompatibility with MIDI 1.0 gear and software. There are even some aspects of MIDI 2.0, such as its improved time-stamping, that can benefit MIDI 1.0 gear.

TWO INTO ONE One of the problems with 37-year old technology is that, well, it’s 37-year-old technology. Although it’s still plenty usable, MIDI 1.0 lags far behind the times when it comes to data-handling. Back in 1983, 128 steps seemed like plenty of resolution. At today’s processing speeds, it’s just a blip. That will change in a big way with MIDI 2.0.

To put it quite simply, says esteemed technology journalist Craig Anderton, “[MIDI 2.0] will provide an analog feel to controls where there isn’t stair-stepping or audible quantization.”

“Just in terms of raw numbers, you’re going from 128 steps at seven bits of data to 4 billion steps at 32 bits,” says Brett Porter, lead engineer at Art+Logic, a software development company that has been a key partner in building code for the MIDI 2.0 project over the past couple of years. He was scheduled to do a presentation at South by Southwest before it was canceled.

But before that cancellation, he recalls, there was a key MIDI 2.0 demo at NAMM that showed how the higher resolution would affect motorized faders. “An engineer from Roland had two motorized faders side by side, and he was driving one of them with 7-bit data, and one of them was 32-bit data. You could see the 7-bit one jumping, while the 32-bit one was smooth.”

Oddly, whereas MIDI 1.0’s shortcoming was not enough data, MIDI 2.0 could have the opposite problem, says Porter. “If you’ve got that 32 bits of data and you’ve got a high-resolution encoder, it’s going to be easy to turn that knob and create way too much data. We’re going to have to start learning how to thin it out intelligently.”

Another longtime complaint about MIDI 1.0 has been that 127 steps of velocity don’t provide enough resolution to faithfully reproduce the nuances of a performance on a MIDI instrument, particularly a piano. That number, of course, is going up in MIDI 2.0. The new spec calls for 16- bit velocity, compared to the current 7-bit data. Under MIDI 2.0, velocity will offer a whopping 65,536 possible Velocity values. And that’s not all.

“One other thing added to the note-on and note-off message was this idea of an attribute,” Porter says. “Every note has this other chunk of data that can go with it.”

That chunk can hold additional note data, which Porter says will particularly benefit, “anybody who is doing microtonal music or Xenharmonic music. They’ll no longer have to set up a tuning table in a synth. They can send the pitch data out as part of the note.”

FORWARD AND BACK Communication in MIDI 1.0 is strictly one way: MIDI In, MIDI Out. That changes in MIDI 2.0, with the adoption of bi-directional data flow over USB or Ethernet. If you’ve ever taken on the tedious job of mapping controllers to software functions, you’ll appreciate one of the most talkedabout additions in MIDI 2.0: Profile Configuration.

“When two pieces of gear connect under MIDI 2.0,” Porter says, “the first thing they’ll do is ask each other, ‘Who are you? What do you know how to do?’” The devices (or a device and a software application) will then automatically configure themselves to work together based on a series of standardized profiles.

Anderton describes a keyboard controller connecting to a DAW running a virtual analog synth plug-in. “A controller can query the instrument, say ‘What are you?’ and upon receiving an answer, assign its controls in a logical way to common parameters like filter cutoff, resonance, envelopes, pulse width, et cetera. “If you opened a different virtual analog synth, the same controls with which you’re familiar would apply,” he continues. “You could control anything with relatively standard parameters—including amp sims, delays, whatever— similarly. Not having to customize hardware constantly to work with software will be a big deal for improving setup, as well as for workflow.” Another new feature, Property Exchange, goes beyond the Image courtesy of MIDI Manufacturers Association generic configuration of Profile Configuration and allows The major components of MIDI 2.0. communication of specific data, such as patches, between devices. Porter gives the following example of how it might work: over from Japan with prototype gear,” Porter says. “They were playing with

“My DX7 is sitting right next to me connected to a rackmount synth. a Yamaha-modified keyboard controlling a Korg-modified synth over MIDI When I press a patch change on the controller, there’s no way for me, when 2.0, with all the new expressivity and resolution, and it worked.” looking at the keyboard, to know that patch 20 happens to be a Rhodes. But there are still more hurdles preventing widespread adoption of It’s just a number. With Property Exchange being able to go across that, a the new standard. One of them is bureaucratic. “We have to wait for the keyboard with a much nicer display is going to be able to say to that synth, USB people to approve the way we want to send MIDI 2.0 data over it,” ‘What are your patch names?’ Which is so obvious. But now we have a Porter says. “And that’s in process. I have no idea how long that takes. mechanism to do that.” Once that happens, then all the companies like Focusrite and MOTU that

“It will be easy to store hardware synth parameters within a DAW,” adds make interface boxes have to update their systems. Apple and Microsoft Anderton, “in a far more obvious—and human-readable—way than Sys Ex. have to update their operating systems. It’s a chicken-and-egg thing, and Signal processors will then become, as far as a DAW is concerned, a plugeverybody behind the scenes is doing what they can, waiting for those in. It would even be possible to retrofit some older synths to do this, but other pieces.” whether there would be an economic incentive is questionable.” It appears that the adoption of MIDI 2.0 is going to happen gradually. “It’s not like we can flick a switch and all of a sudden, MIDI 2.0 comes out WHAT’S THE TIMELINE? the other end,” Anderton points out. “The prioritization on backwardAll of these new capabilities sound fantastic, but gear with MIDI 2.0 compatibility means new features can roll out over time. It will also be support isn’t yet available, nor is there support among DAWs and plugpossible to buy products where MIDI 2.0 is dormant, as it waits for other ins. One exception is the Roland A-88MKII keyboard. On its website, the products to appear. Then one day, that product wakes up to find other company says it is “ready to take advantage of the extended capabilities of MIDI 2.0 gear with which it can converse.” MIDI 2.0,” although it hasn’t specified what that readiness entails. While we wait for MIDI 2.0 to gradually penetrate the market, we

Several companies have shown working prototypes, as was evident at the have time to say an extended goodbye to MIDI 1.0, and to marvel at its MMA annual meeting at NAMM. “Roland, Korg, and Yamaha sent engineers longevity. ■

The Roland A-88MKII keyboard is the first commercial product to offer MIDI 2.0 functionality.