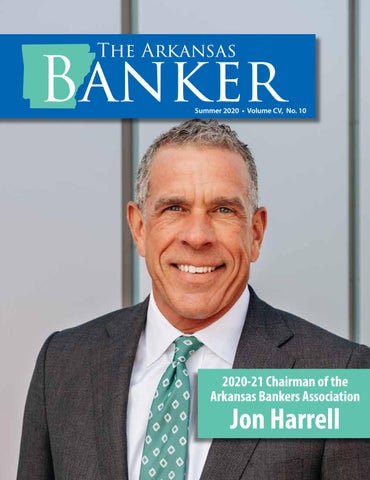

13 minute read

Community Bank Stress Testing for the COVID-19 Shock

Stress-Testing Reduces the Uncertainty ike the financial crisis period, the COVID-19 crisis is again exposing community banks to a severely adverse shock. 1 Arguably, the uncertainty associated with this shock is greater than the uncertainty experienced in 2008 at the onset of the financial crisis because there is no modern precedent for a global shock that has disrupted such a large swath of households and firms. Indeed, 3.28 million l U.S. workers filed unemployment claims for the week ended March 21, nearly five times the previous record high. 2

Given the uncertainty, a bank stress test is a useful tool to make an educated guess as to how banks will be affected by this crisis. Stress-testing provides insights to potential worstcase conditions in the banking industry, which provides opportunities for bankers, regulators and policymakers to better prepare. With preparation, damage to banks’ balance sheets can be reduced, allowing them to continue to lend to creditworthy households and businesses to promote economic recovery.

Bank stress testing is an even more relevant exercise for the COVID-19 shock than for previous crises. A stress test assumes that all banks go through an adverse scenario to provide a worst-case outlook for each bank. But we know prior to the stress test that only a subset of banks will experience the worst-case outcome because only a subset of firms and households are severely affected by the shock, and banks differ in their exposure to these entities. The COVID-19 shock more uniformly applies to all banks because the shock has driven even financially healthy firms and households into distress. In other words, even well-managed banks with low-risk profiles are directly hit by this shock. A stress test in this context is more likely to accurately portray the distress of a large proportion of banks.

An Historical Loss Approach

The community bank stress test we developed after the 2007- 2009 financial crisis uses an historical loss approach to estimate five-year changes to bank capital from a severely adverse shock. 3 It does this by applying chargeoff rates derived from banks’ actual chargeoff rates between 2008 and 2012, which encompasses the recession and recovery following the financial crisis. Specifically, chargeoff rates applied to each bank in a local market are taken from the 90 th percentile chargeoff rates of all banks in the market. For example, the chargeoff rate for commercial and industrial loans for a bank in the first year of the five-year simulation is the 90 th percentile chargeoff rate experienced by banks in its market in 2008. The chargeoff rate for the second year is the 90 th percentile chargeoff rate of those banks in 2009, and so on through 2012.

An advantage of the historical loss approach is that the financial crisis shock provides a severely adverse scenario that serves as a benchmark for future crises, and it bypasses the need to use econometric approaches to map changes in economic conditions into banks’ chargeoff rates. A disadvantage is that future shocks are assumed to be identical to the benchmark scenario.

U-Shaped or V-Shaped Business Cycle?

The adverse scenario for the COVID-19 stress test should reflect the forecasted macroeconomic conditions that will ensue. Our default adverse scenario from the 2008-2012 period is a U-shaped business cycle where the economic decline persists for two years (2008-2009) and the recovery is relatively slow. In contrast, analysts expect a V-shaped business cycle resulting from the COVID-19 shock because once households and employees can move freely again, demand for goods and service will resume and most businesses will return to normal production levels quickly. The quick response by the Federal Reserve and the $2 trillion economic relief package passed by Congress in late March will also assist the economy recovery.

Using 2019 as the base year (Y0) to establish initial conditions, we adjust our financial crisis shock to reflect GDP growth expectations for 2020-2024. Figure 1 plots real GDP growth rates for two different scenarios, each beginning with the actual 2019 GDP growth rate of 2.3%. The U-shaped series plots actual growth rates between 2008 (Y1) and 2012 (Y5), and it represents the economic growth pattern of our default financial crisis stress test. The V-shaped line in Figure 1 plots forecasted growth rates between 2020 and 2024 in response to the COVID-19 shock. These forecasts have a wide dispersion. The Conference Board, Goldman Sachs, and Wells Fargo, respectively, forecast 2020 growth rates of 1.4%, -3.8%, and 0.5%. 4 We assume that growth in 2020 (Y1) is the average of the three values at -0.6%. Most forecasts assume that economic growth rebounds quickly thereafter, so we assume 2% GDP growth rates for 2021-2024 (Y2-Y5).

Figure 1. GDP Growth Rates by Scenario

Y0 Y1

U-Shaped Y2 Y3 Y4

V-Shaped Y5

In sum, the COVID-19 shock is initially more severe than the financial crisis shock, but the recovery is much quicker. The GDP growth rate is forecasted to be 0.5 percentage points lower in 2020, and 4.5 percentage points higher in 2021 than actual growth rates during the financial crisis.

Chargeoff Rate Adjustments

We alter the stress-test chargeoff rates from the financial crisis years to account for the different economic dynamics of the COVID-19 scenario. The initial known chargeoff rate in 2019 is 0.2%. We double the chargeoff rates from 2008 and apply them to 2020 (Y1). We use the actual 2009 chargeoff rates in 2021 (Y2), and we set chargeoff rates at 0% for 2022-2024 (Y3- Y5). The doubling of Y1 chargeoff rates reflects the more rapid economic deterioration in 2020 relative to 2008. The same 2009 chargeoff rates for Y2 capture the lagged effect on bank performance from the distress of firms and households that spills over from the initial shock in 2020. Finally, the zero chargeoff rates thereafter reflect the quick recovery. Table 1 presents a comparison of the mean chargeoff rates for the financial crisis scenario based on the U-shaped business cycle, and the COVID-19 scenario based on the V-shaped business cycle.

Table 1. Mean Chargeoff Rates by Scenario

Year

2019 (Y0) 2020 (Y1) 2021 (Y2) 2022 (Y3) 2023 (Y4) 2024 (Y5)

Financial Crisis

0.2% 1.0% 2.2% 2.2% 1.9% 1.3%

COVID-19

0.2% 2.1% 2.2% 0% 0% 0%

Stress Test Results

We run community bank stress tests on both the COVID-19 scenario and the financial crisis scenario. The latter scenario would become more relevant should the effects from COVID-19 persist much longer than the March 2020 forecasts. For both scenarios, 2019 is the initial year (Y0), and the fiveyear projections are from 2020-2024.

We first project the number of banks that are in danger of failing from each adverse scenario. When a bank’s Tier 1 leverage ratio (Tier 1 capital to total assets) dips below 2%, Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) guidelines mandate that regulators must close the bank if the bank does not present a credible capital restoration plan.

Figure 2 shows the number of distinct banks through the given year of the simulation with a Tier 1 leverage ratio below 2%. Community banks are projected to fail at a faster pace in 2020 and 2021 in the COVID-19 scenario. Of the 4,432 community banks at year-end 2019, 50 of them dip below the 2% threshold from the COVID-19 shock, but only 26 banks cross that threshold from the financial crisis shock. None of the 82 Arkansas community banks is projected to fail by 2021 in either scenario. (Continued on next page.) The Arkansas Banker n Summer 2020 23

Figure 2. Number of Banks with T1Lev <2%

250

237

200

150 179

100

50

0 50 97

57 65 68

Banks, however, weather the COVID-19 scenario much better than the financial crisis scenario over the five-year horizon because the economic recovery is much quicker. Just 68 banks (1.5%) are projected to fail by 2024 in the COVID-19 scenario, but 237 banks (5.3%) are projected to fail from the financial crisis scenario. Just one Arkansas community bank is projected to fail in 2023 in both scenarios.

We also project the number of banks that become severely distressed even if failure is not imminent. We define a seriously distressed bank as one whose Tier 1 leverage ratio falls below 6%. The 6% threshold, which is roughly half the mean capital ratio of community banks in 2019, implies that banks may have to curtail credit supply to preserve capital, which can exacerbate the downturn and slow the recovery.

Figure 3 plots the number of distinct banks through the given year of the simulation with a Tier 1 leverage ratio below 6%. The results show the same pattern as Figure 2. By 2021, 262 banks fall below the 6% threshold from the COVID-19 scenario, nearly double the 140 banks from the financial crisis scenario. Two of those banks are headquartered in Arkansas. Over the full five-year horizon, however, just 289 banks (6.5%) cross the threshold from the COVID-19 scenario while the comparable number for the financial crisis scenario is 637 banks (14.4%). Two Arkansas community banks become severely distressed in the COVID-19 scenario, and five banks in the financial crisis scenario.

The average bank projected to become severely distressed from the COVID-19 scenario is larger than the median community bank and operates primarily in urban markets. The mean severely distressed bank holds assets of $655 million at yearend 2019, and 87% of the banks are headquartered in urban markets. This patter exists because, even when adjusted for a

V-shaped business cycle, the 90th percentile chargeoff rates taken from the years 2008-2012 reflect the geographic pat24 The Arkansas Banker n Summer 2020

1.17% 800 1.17% 1.11% 1.11% 1.11%

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0 2019 .68%

367

383 .46% 272 281 289 .14% 262 .16% 86 .01% 140 00 -.01% 32 -.03% 2019 2020 2020 2021 2021 2022 2022 2023 2023 2024 2024 Financial Crisis Financial Crisis COVID-19 COVID-19

terns of the financial crisis shock. During those years, banks in large urban areas with greater exposure to construction and land development (CLD) loans were hurt the hardest. Our projections retain this influence. Indeed, there is reason to believe that community banks most exposed to the COVID-19 shock also operate in large urban markets because the population density fosters conditions for the virus to spread more easily. Of the 262 community banks projected to dip below the 6% Tier 1 leverage threshold by 2021, 159 (61%) of them are headquartered in the five states of Florida, Michigan, Illinois, Georgia, and Minnesota.

Figure 4. Mean ROA

1.17% 1.17% 1.11% 1.11% 1.11%

.68%

.46%

2019

In addition to capital ratios, we project bank profitability during the stress test scenarios. Figure 4 plots mean return on assets (ROA) between 2019 and 2024. Banks begin the stress

test with a healthy ROA of 1.17%. In the COVID-19 scenario, ROA is projected to dip to just one basis point in 2021, but it rebounds quickly close to pre-shock levels at 1.11%. ROA for the financial crisis scenario decline and recovers more slowly. ROA is 0.68% in 2020 and hits its trough in 2022 at -3 basis points before slowly rising to 0.46% in 2024. The higher profitability for the COVID-19 scenario after 2021 again reflects the quick recovery. Arkansas community banks show similar profitability trends for both scenarios.

In sum, the COVID-19 stress-test scenario results in somewhat more banks failing or becoming severely distressed during the first two years of the simulation relative to the financial crisis shock. However, bank health rapidly improves thereafter so that the number of severely distressed banks after five years is far less than the number of severely distressed banks from the financial crisis scenario. The latter scenario, however, will become more relevant if the effects from COVID-19 persist longer than currently anticipated.

Banks Are Better Prepared for a Shock

Regardless of the damage that economic disruptions from COVID-19 may impose on the banking industry, banks are better prepared to absorb an adverse shock than they were in 2007. Compared with 2007, community banks hold fewer CLD loans, and fewer banks have relatively low capital ratios. In 2007, the mean CLD loan to total loan ratio was 12%; in 2019 it was 6.3%. Similarly, in 2007 nine percent of banks had a Tier 1 leverage ratio less than 7.5% versus just one percent of banks in 2019. For both scenarios, our stress-test failure projections are much lower than they were for banks in 2007. From Figure 2, we project 68 community banks to fail from the five-year COVID-19 scenario, and 237 to fail from the financial crisis scenario when 2019 is the base year. In contrast, the financial crisis scenario using 2007 as the base year projected 762 failures. In fact, 386 community banks failed between 2008 and 2012. Higher capital and lower inherent credit risk have made banks less vulnerable to shocks in 2019 than in 2007.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, banks are confronted with the economic shock from COVID-19 only a decade after the financial crisis. Our historical loss community bank stress test provides a tool to quickly assess banks’ capital sufficiency during a five-year shock resembling the financial crisis. The shock from COVID-19, however, is likely to be shorter in duration but more severe initially so we adapt our financial crisis scenario to reflect a V-shaped business cycle shock.

The COVID-19 stress test scenario projects that through 2021, 50 banks will fail versus 26 banks from the financial crisis scenario, but none of those banks are headquartered in Arkansas. Over a five-year horizon, however, the results are reversed. Just 68 banks are projected to fail from the COVID-19 scenario relative to 237 failures from the financial crisis scenario, and one of those banks is chartered in Arkansas. In addition, nearly 90% of the severely distressed banks are headquartered in urban areas, and most reside in the more populous states. Current expectations are for a V-shaped business cycle, which makes the COVID-19 scenario more likely. We caution, however, that economic forecasts are highly uncertain. If the COVID-19 virus were to disrupt production and consumption for a prolonged period, the adverse effects on the banking industry would more closely resemble the projections from our financial crisis scenario.

Fortunately, both the COVID-19 and financial crisis stress test scenarios show significantly less adverse effects on community banks than the actual damage that resulted from the 2007- 2009 financial crisis and Great Recession because banks are better prepared to absorb an adverse shock than they were in 2007. Even if the current economic shock is prolonged, the banking industry should fare better than it did between 2008 and 2012.

Timothy J. Yeager is Professor of Finance and holds the Arkansas Bankers Association Chair in Banking at the University of Arkansas. Cao Fang is a doctoral student in the Finance PhD program.

Notes 1. Community banks are those with less than $10 billion in real total assets. 2. Wall Street Journal, “Record 3.28 Million File for U.S. Jobless Benefits,” March 26, 2020. 3. For more information on the stress test model, see our working paper, “An Historical Loss Approach to Community Bank Stress Testing,” available at https://walton.uark.edu/ departments/finance/community-bank-stress-test.php 4. The Conference Board, “The Conference Board Economic Forecast for the U.S. Economy,” https://www.conferenceboard.org/data/usforecast.cfm, accessed March 25, 2020; Goldman Sachs Research, “US Daily: A Sudden Stop for the US Economy,” March 16, 2020, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/usdaily-20-march-2020.html, accessed March 25, 2020; Wells Fargo Monthly Economic Outlook, Forecast Update: Global Downturn Imminent, March 16, 2020, https://www.wellsfargo.com/com/insights/economics/ monthly-outlook/, accessed March 25, 2020.

20 th

celebrating 20 years of providing safety & security for senior citizens

Protect local seniors from elder abuse

while earning CRA credit Endorsed by

Our turnkey CRA compliance program powered by the Senior Housing Crime Prevention Foundation is helping seniors right now in facilities nationwide with programs that educate and guard against theft, abuse and neglect. Sponsor a home near you today, when seniors need our help more than ever.