8 minute read

THE DICK STANLEY REQUEST

In March 2015, Jamie Diamond, a photo-based artist, received an email from one Richard “Dick” Stanley. Mistaking Diamond for Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., Stanley stated that he had been a Chase customer in Columbus, Ohio, since 1996, but had recently moved to Albuquerque, where he had to bank long-distance. He wanted to know why there were no Chase branches in New Mexico. “I know how busy you must be, but if you find the time please let me know,” he wrote.

Diamond had had numerous cases of mistaken identity with Dimon over the years; people had tried to sell her things or invite her to parties. But this request was gentle and curious, and it stayed with her.

The artist’s wider work involves similar elements of chance: For prior projects, she has hired actors to unknowingly perform as members of her family (including fashion designer Wayne Diamond, her father), staged couples portraits of strangers found on Craigslist, extensively explored motherhood, and, more recently in Skin Hunger, documented the world of professional cuddlers who provide nonsexual intimacy to paying customers, both in person and virtually. For Diamond, who also teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, image production—through the creation of photos, videos, and performances—is a way to explore our collective desire for intimacy, even if it is achieved through a staged encounter. (“I am interested in photography’s role in the construction of personal myth and the fabrication of memory, as well as the disparity between image and reality,” she wrote in an artist’s statement.) What remains is the documentation of an alternate world, convincingly furnished through the tricky medium of photography.

A few years later, Diamond decided to honor Stanley’s request. In early 2022, she flew to Albuquerque for a first-time visit and became familiar with the city and the landscape. With the photographic history of American’s westward expansion in mind, she identified and documented three potential sites: one in the suburbs northwest of the city, one within Petroglyph National Monument, and, farthest west, one in the desert near an Amazon fulfillment center 1

Part of the artist’s interest was in the increasingly evanescent physical presence of banks in the U.S., as the building type’s architectural evolution showcases how the visual language of power and authority has progressed. In the early 20th century, banks were impenetrable, fortified temples clad in stone to secure, within their vaults, money as a physical thing. Post-1929— and even more so postwar—banks adopted the International Style to suggest a modern language of security, stability, and transparency. Diamond cites SOM’s glassy Manufacturers Hanover Trust, completed in 1954, as an example of this epoch. Since then, banking has become dematerialized, from anonymous roadside bank branches to ATMs to websites to smartphone apps.

Like much else, the answer to the question of “Where is my money?” might be that it exists distributed among servers around the world. Why, then, should a bank have a physical location at all?

Cryptocurrency further destabilizes the situation, as the technology relies on blockchain technology instead of a central agency to verify the value of currency. The unique identification properties of the “coins” that are traded have reshaped other fields, like art: The rise of the non-fungible token (NFT) has spurred intense interest from artists and collectors alike, and marketplaces have emerged. Large sums of money have quickly been accumulated: A single NFT artwork by Beeple was auctioned by Christie’s in March 2021 for $69 million, and a release of 250,000 NFTs in December 2021 netted the anonymous artist Pak $91.8 million.

The craze has since cooled, as a crash in the spring of 2022 saw the loss of about $2 trillion in value. Trading platforms have folded, and the exchange FTX and its founders are under investigation. Pre-crash, JPMorgan issued a report about opportunities in the metaverse for consumers and brands: “Whether it’s large tech players such as Microsoft planning to create realistic workspaces, or Ariana Grande holding a concert in Fortnite, the opportunities presented by interactive, digital worlds seem limitless.” Post-crash, Dimon called cryptocurrencies “decentralized Ponzi schemes,” and, two months later, he disparaged them again, likening them to “pet rocks.”

To respond to Stanley’s inquiry, Diamond commissioned six architects to produce schemes for branches beyond the limitations of “humdrum bricks and mortar” and asked them to consider two questions: What is the future for banking as we know it in the face of decentralized finance and the blockchain? Are we building an architectural model for the future of banking, or a monument to obsolescence?

The architectural responses, explored via video and image, vary widely in how “building-like” each vision appears.

Gordon Kipping’s proposal 2 began from the provocation of Elmgreen & Dragset’s Prada Marfa, in which an interior is visible but not accessible. He took the installation’s dimensions and re-created them in an “inaccessible and empty” minimalist box. Above a concrete slab, laminated glass walls support a CLT roof concealed behind LED screens on all four sides. “The sign is emblazoned with a modified JPMorgan Chase bank logo to evoke its evolution to the cryptosphere,” according to a project statement. A rooftop solar installation powers the apparatus, which is ventilated to avoid condensation. Prior work by Gordon Kipping Architects also trafficked in public pixelation: A proposal for the City of Newark showcased a series of scrolling signage displays along with phytoremediation to beautify shared urban spaces.

Another minimal box was envisioned by Ricardo Umansky of Studiometria Design Group 3 . His mirrored, elongated facade attempts dematerialization. Set against the backdrop of the Sandia Mountains, it floats above the desert and is accessed from a walkway lined with illuminated bollards.

The video version of the scheme shows the facade over the course of a single day, transitioning from reflecting the sun and sunset to, at night, projecting a Matrix-like grid of vertically scrolling characters while a rocket launches in the background.

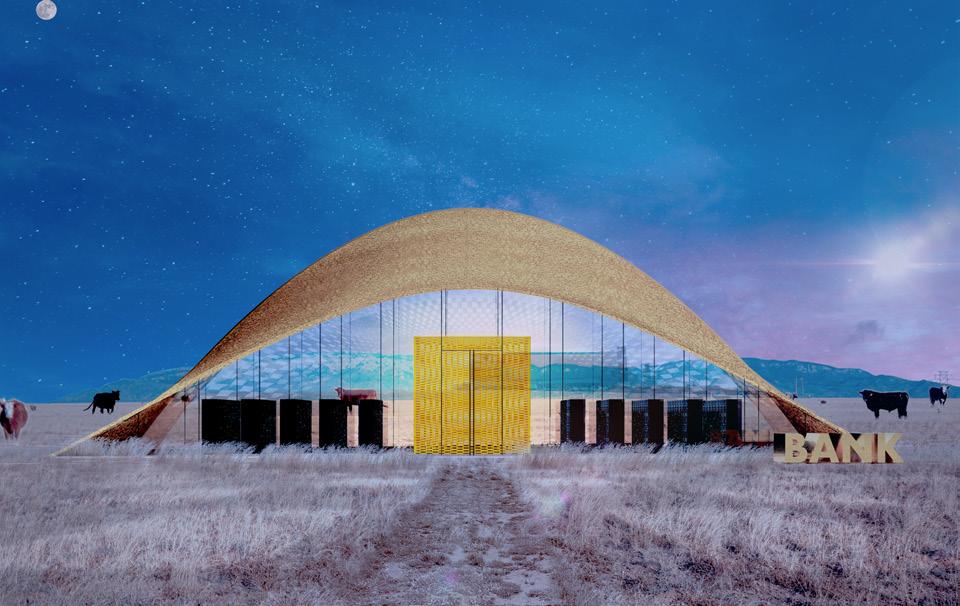

Au by Dana McKinney and Megan Echols of enFOLD Collective 4 imagines a future where gold is so worthless it can be used as a solid building material. Here, a gold dome encloses a “concourse of servers hosting clients’ blockchain data” and, at its center, a smaller vault made of gold bars “encases a private sanctum where clients can fund, transfer, and mine their crypto accounts.” While the commission is different from enFOLD’s typical efforts— the firm seeks out “projects that have community-driven impact and that elevate justice, Black identities, and wellness”— the architects still managed to “engage the evolution of the banking industry through a deep investigation of its histories, playful theory, and admittedly a lens of skepticism” to arrive at a critique of conspicuous consumption and capitalism more broadly.

The proposal by Kelly D. Powell 5 , founder of 222 East Society, begins from Chase’s octagonal logo, designed in 1961 by Chermayeff & Geismar Associates, and pitches a boutique interior space that, after business hours, could become an event space for community gathering. What looks like a concrete bunker with an ornamental entry screen on the outside becomes a stepped forum on the inside. Like high-end retail, the value of meeting in either medium is about exchange, not economy. Lamenting the poor quality of most metaverse spaces, Powell suggests the virtual version should exactly match the physical version; though she specifies a maximum of two clients at a time for “pre-scheduled private banking appointments,” there is no limit to the number of patrons in the virtual branch bank.

David Bers, of David Bers Architecture, took inspiration from SOM’s Chase Manhattan Bank 6 , completed in 1961 and demolished in 2021 to clear space for Chase’s new headquarters. His proposal is a virtual reconstruction of that building “populated by spirits of Albuquerque’s indigenous animals, who play the role of surrogate guides for Mr. Stanley in an interactive bank experience.” (The fauna are in response to JPMorgan Chase’s lounge in Decentraland, which hosts a roaming tiger, in addition to a portrait of Dimon.) The VR experience would be accessible only when the user is physically on-site in the desert. As one moves through the ghostly architecture, the apparitions play the role of bankers: The “spirit animals” will be “portkeys” that, upon approach, unlock “various sensory media experiences of banking.”

Sotirios Kotoulas proposed an “inverted stone pyramid carved into the earth” that “mediates energy flows and frames the sky and landscape 7 .” Within, flickering transactions across the electromagnetic spectrum are given a hallucinatory presence as packets of energy. “I am interested in a metaverse architecture that centres the human and does not mimic the forms and spaces of our physical world,” he shared via email. Previously, “banks embraced banality and anonymity for the bored consuming masses.” Kotoulas believes “the bank is now ready to abandon physical branches and fully enter the realm of the senses; penetrating bodies, neurological networks, and perception, the bank can be everywhere and nowhere.”

The architects praised Diamond for the supportive and open collaborative environment she established when working with them on the project. They also said they learned more about how the metaverse might be a productive realm through which architects could design space. Kotoulas speculated that “architects should think about the material properties of this medium to create a new space for human inhabitation that avoids all precedent” and added that NFTs offer a new frontier that’s a “wild west full of unleashed talent, fraudsters, and bank robbers.” enFOLD shared that they “also see digital art, NFTs in particular, as a means to give new life and direction to unbuilt works.”

Upon completion, Diamond shared the results with Stanley via email. “I really don’t know how to thank you for what you did. I was about to transfer both my dollars to another bank,” he replied. “All this time I thought Chase was just ignoring me.”

In the years that Diamond has been working on The Dick Stanley Request, Dimon was busy with his own architectural commission. As mentioned, Chase’s prior skyscraper in New York was demolished to make way for 270 Park Avenue, a new global headquarters for JPMorgan

Chase designed by Foster + Partners. Able to accommodate 14,000 workers and slated to be the city’s largest all-electric tower, it stands to offer the company’s vision of the future of the office in the midst of the industry’s continued etherealization. “We are extremely excited about the building’s state-of-the-art technology, health and wellness amenities, and public spaces, among many other features,” Dimon stated in a press release. Completion is expected in 2025 at a cost of nearly $3 billion.

Last fall, Diamond spent time crafting a pitch deck to share The Dick Stanley Request with Dimon and ultimately did transmit it to Chase. She hoped the company would want to participate in or even purchase the artwork. While it is unclear whether Dimon has seen the project, a representative shared that he “would pass on commenting” to AN.

Diamond plans to mint her artwork as an NFT, but because the market remains volatile, she is waiting to set a date for that release. NFTs are, in her view, “a perfect way to have that permanent record of your work exist infinitely.” She is also interested to show the work in a physical exhibition or even commission another round of architects as the project evolves. The experience was different from her other participatory pieces because “it was a collaboration,” Diamond said. “In coming together, there was this solidarity and unity. It was nice to share those ideas.”

Today Chase has six bank branches in Albuquerque. JM