5 minute read

Chancellery

CHANCELLERY COMMANDER CHIK BRENNEMAN ANSWERS THE QUESTION: WHAT’S IN A GRAPE?

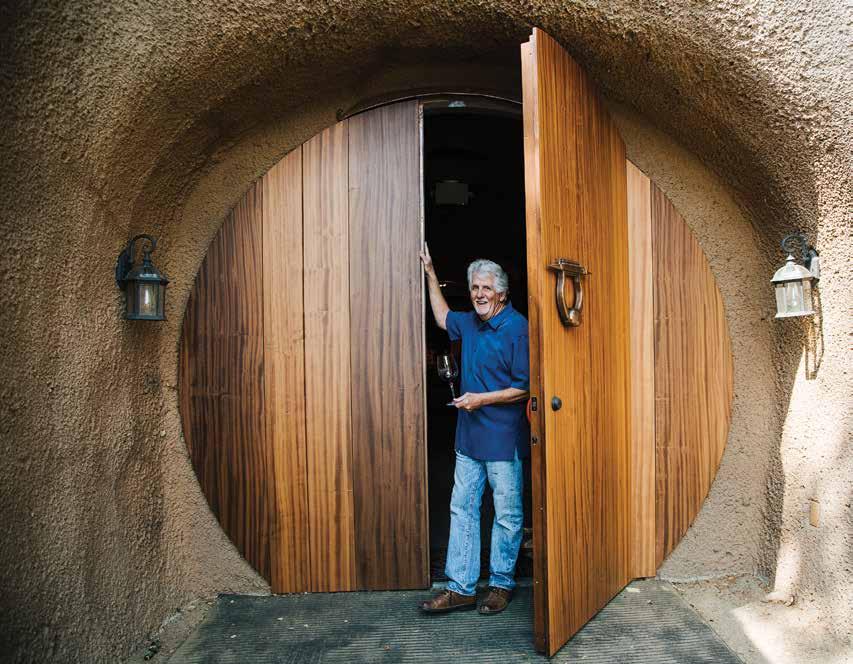

As a winemaker, I have always held the belief that great wines are made in the vineyard. Therefore, I make a point to listen to the viticulturists whose expertise is in matching the right grape variety to the appropriate rootstock. Their understanding of the soil type, the local microclimates, and topography is a complex process, and in many areas of the world, has taken centuries to master. The challenges of grape variety selection are also compounded by local pressures such as diseases, pests, and weather that challenge the grower during the growing season. Powdery and Downey mildew, Pierce’s Disease, and bird and insect pressure are just some of the challenges. But just as in the medical field, researchers strive to find cures or come up with preventative measures for common and rare maladies. In the vineyard, intervention with fungicide sprays can tackle a host of problems, but there is a movement towards decreasing the use of chemicals and development of some sort of resistance mechanism. As more and more regions outside of the traditional temperate winemaking zones open up to grape growing and wineries, extreme temperatures become problematic. The unsung heroes now are the botanists and geneticists who specialize in breeding better grape varieties, not just for disease resistance or finding a better variety for a particular site, but also to perhaps find a better tasting grape.

Breeding plant varieties is nothing new. Botanists have been doing this since what seems like the beginning of time. With more knowledge about genetics, science in some plant fields has resorted to genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, to accomplish the task. GMOs are now looked at negatively even though they have been around for some time. The grape breeding industry is sensitive to this stigma and, while the technology is there to insert specific genes into the grape genome for a desired outcome, grape breeders have chosen a classical breeding approach. Classical breeding is essentially cross-pollinating vines that you find have desired characteristics, like disease resistance, into other vines that have other characteristics that would be enhanced by the cross.

Most crosses are based around Vitis vinifera spp. This is the European wine grape where the “spp” suffix represents Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Syrah, etc. As V. vinifera expanded beyond the European continent, it had no resistance to the pests and diseases where it was introduced. The most notable example of this was the phylloxera scourge of the 1860s in France that subsequently spread to North America. Phylloxera is a root louse, native to North America that made its way to England via cuttings of native American grapes. It was inadvertently introduced to France, and subsequently, devastated the French wine industry. By the 1870s, the world looked to California for wine. California had been planted with V. vinifera by settlers who traveled there for the gold rush. California subsequently suffered its own scourge of the pest. Breeders scrambled to cross-pollinate vinifera with the native North American grapes, which are commonly known as the French-American hybrids, but the acceptance of the flavors introduced by the native grapes was not well received. Ultimately it was not breeding that saved vinifera, but knowledge of the native grapes in using them for rootstock, and grafting vinifera to them.

It was this first knowledge with phylloxera that became the basis for grape breeding programs. If you cross the two species enough, you should be able to dilute the undesirable flavor characters while not diluting the desired characteristics. The first cross is 50% vinifera. When this first progeny is crossed with another vinifera the second progeny is 75% vinifera and the lineage goes on with each of these generations taking time to grow, get to an age where they develop fruit and then these small quantities of fruit can be made into wine. A slow approach but made a little easier in that DNA sequencing can be done in the early generations to determine if the desired genes were carried forward. Huge volumes of seeds are generated, which are grown up in the greenhouse, screened, and possibly dumped. One generation can produce almost 10,000 seedlings! Only a small percentage make it to the next generation.

What goes first into breeding the ‘better’ grape variety is to identify the issue that needs to be overcome. It could be that someone is just trying to make a grape that tastes better or is easier to grow. Disease resistance to Powdery or Downey Mildew and Pierce’s Disease were programs that I participated in during my tenure at the University of California, Davis, but there are other programs across the United States and the world. Some notables are at the University of Minnesota and at Cornell University where cold and cool hardiness is addressed. While in Brazil, researchers are looking at growing wine and table grapes in tropical regions by understanding the native varieties and incorporating their native resistances into other Vitis grape species that are brought in from Europe or North America. And we cannot overlook the backyard breeders who just like to tinker. I think one of the more interesting stories highlighting that group is that of Dr. Daniel Norborne Norton, a medical doctor whose work is recognized by the naming of the “Norton” grape. That’s another story, for another time. These researchers are the unsung heroes that are shaping our industry. They are not the winemakers, rather they are the wine ‘shapers’ whose dedication and patience (it can sometimes take up to twenty years to get a variety bred, evaluated, and patented) anticipate the future trends in an industry in which consumer preference is so important.

An important piece of the puzzle is consumer acceptance. The French-American hybrids, while still grown in small quantities in France, are banned in the European Union. And importation of hybrid wine into some countries is prohibited. The world’s most popular wine grapes, V. vinifera are what the consumer desires, but they cannot be grown just anywhere. In the United States, wine regions are springing up and, as consumers are thinking local, if they are in a colder region, they may choose one of the cold temperature tolerant hybrids. More moderate climates that may have humidity issues may choose varieties that are resistant to mildew. The Pierce’s Disease resistance project has led to numerous varieties being developed and planted in the southern United States.

While I have an appreciation for all wines, I find the hybrid programs to be an amazing movement and anywhere we travel, we seek out those wineries that take in a ‘what works best for them’ philosophy and craft their art. Wines are made in the vineyard and every region has its own potential. It’s all about the right variety in the right place.