5 minute read

A Story In Stones

The Roslyn Cemetery: Remembrance Of Things Past

By Mike Adams

Advertisement

ou can tell a lot about a community by how it treats its dead. Roslyn is no exception.

The Roslyn Cemetery, nestled on the border of Greenvale and East Hills near the Nassau County Museum of Art and the Sid Jacobson Jewish Community Center, is as much a product of its time and age as anything in the community. Founded in 1861 in the wake of the Rural Cemetery Act, the burial grounds were one of many dug into the countryside surrounding New York City in response to an increasing shortage of space.

The cemetery and the adjoining Roslyn Presbyterian Church were nearly alone on the landscape when they came into being, but that’s not the case anymore. Now they’re sandwiched in between a set of railroad tracks and Northern Boulevard, with power lines looming just overhead. But a strange thing happens within those walls: despite the modern world that beckons just outside, the cemetery is an oddly calm place, a plot of rural peace sectioned off from sprawling chaos. On a sunny day, when the light peaks through the branches of the mighty trees that dot the place, it’s downright beautiful.

Death is an uncomfortable reality lurking at the end of all our lives. Cemeteries can be just as uncomfortable, since they embody that inescapable truth. But the Roslyn Cemetery is much more than a holding place; it’s a time capsule for the community, a history of the people who called this place home, told in so many stones.

There’s a perceptible shift in demographics as the dates on the graves move later and later. The oldest stones rest atop members of some of Roslyn’s oldest families. The Kirbys, the Smiths, the Tabers and the Remsens; the same names appear again and again, often with worndown engravings that are just faintly visible. As the 20th century makes Y

its way into the cemetery, the Anglo-Saxon surnames start to be joined by Irish, Italian and Eastern European families that fought their way into social acceptance before the Second World War. Later on, some of the more modern graves are adorned with Chinese, Arabic and Farsi calligraphy. Death is a great equalizer, and people who very well may have been so prejudiced they could not stand each other now find themselves in plots just feet apart from one another. One can only hope they’re getting along in the next life.

Many of the graves are set aside for people who served their communities as firemen, police officers and soldiers. For the soldiers in particular, a monument to those lost in the Civil War stands a short way down a path from the main entrance. It’s a simple thing: a bronze statue of a soldier standing atop a column ordained with stars, built and dedicated by the Elijah Ward Post of the Grand Army of the Republic formed by veterans after the war. The statue itself is a replica of the original, which was replaced in 2005 after being stolen from atop its pedestal in 1992. From a distance the soldier seems grand and glorious, but the grief in the statue becomes more apparent up close. His right hand clutches the barrel of his rifle, which he leans on somewhat as if using it like a cane. There’s a deep sadness in his eyes, fitting tribute to all who gave the last full measure of their devotion to the nation, then and now.

Some of Roslyn’s most famous figures are interred at the cemetery, and their graves offer precious clues into the kinds of people they were when they lived their lives. Perhaps the most famous of all the cemetery’s inhabitants, William Cullen Bryant and his loved ones take up their own modest plot beneath a massive tree carved with the initials of visitors past. The renowned author shares an obelisk with his wife Frances and their two daughters, Julia and Fanny, that stands above more modest tombstones for himself and many members of his extended family. The pharaohs built entire pyramids in a mad rush to be remembered; that Bryant would elect to take just a quarter of a far smaller monument, and share space with his family, is an obvious sign of the love they had for each other.

Frances Hodgson Burnett is buried below a flat stone grave with some of her closest friends and her second son, Vivian. A life-sized stone sculpture of her first son Lionel stands a short walk away. Lionel predeceased Burnett when he succumbed to tuberculosis in 1890, at 16 years old. After decades apart, it’s touching to see the two reunited in some small way at the end of her path.

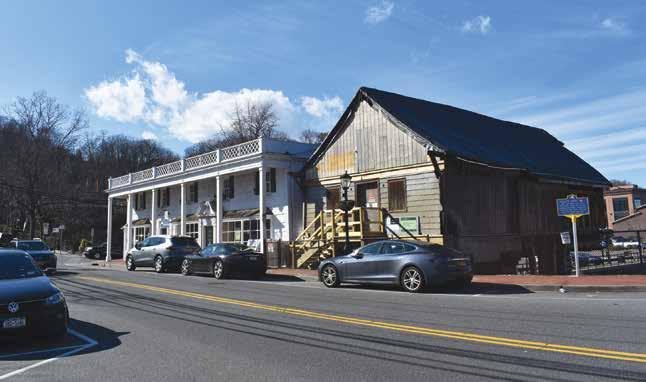

Top: The East Gate Toll House that used to serve North Hempstead Turnpike. Right: A porcelain angel left at the foot of an old grave. (Photos by Mike Adams)

Left: A bronze statue of a soldier, a monument to those lost in the Civil War. Down: A stone mausoleum just off the path of the cemetery.

Left: The plot of land that makes up the Roslyn Cemetery viewed from above. Right: A more recent grave, adorned with Farsi calligraphy for Fateme Navabi.

Left: The graves of late U.S. Congressman Stephen Taber and his wife.

THE DUX BED

INTRODUCING THE DUX 8008

CELEBRATING 90 YEARS OF INNOVATION

The DUX Bed’s customizable component system is designed to resist gravity and weight to provide continuous, pressure-free support.

REMOVABLE TOP PAD UP TO 4,188 SWEDISH STEEL SPRINGS

PASCAL CUSTOMIZABLE SPRING CASSETTE SYSTEM

ADJUSTABLE LUMBAR SUPPORT

THE DUX BED IS AVAILABLE ONLY AT

3-L AYER CONTINUOUS COIL SPRING DESIGN