22 minute read

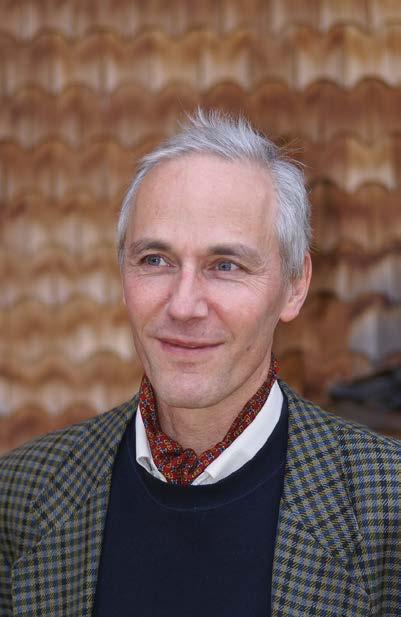

Interview: Johannes Kühl of the Natural Science Section

by Robert McKay

Johannes Kühl was born in 1953 in Hamburg, Germany. He studied physics in Hamburg and Göttingen, and worked on fluid dynamics at a Max Planck Institute. After studying at the Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum, he taught physics, chemistry and mathematics at the Stuttgart Uhlandshöhe Waldorf school. Since 1996, he has been the leader of the Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum and a member of the Collegium of the School for Spiritual Science. His research interests include Goetheanistic optics, quantum physics, fluid dynamics, and the relation of technology and culture. He is the author of a number of books and articles including a wonderful book on rainbows and other atmospheric colors that will soon be published in English translation by Adonis Press. He is married and has four adult children.

Advertisement

Question 1 – How did you first encounter anthroposophy? Can you tell us something of your journey in becoming an anthroposophist?

I was born to anthroposophical parents and went to a Waldorf school so I was destined to meet anthroposophy. Of course, there are many steps or levels of coming to know anthroposophy. One important step for me came in the ninth grade, when I was fifteen years old. Several students, myself included, asked one of the teachers to tell us something about Rudolf Steiner. We knew that the school had an anthroposophical background and that this had to do with Steiner but we wanted to hear what this was really all about. The teacher thought about it for a while and then agreed to work with the students but only in the afternoon after school was over. The work would not be part of the school but had to be a separate activity. This led to the formation of a study group that included several teachers and about twenty high school students. We worked through various texts and lectures over several years. That was the beginning of my study of Rudolf Steiner.

Now, if you are born into anthroposophy as I was, there comes a certain moment where you have to decide if anthroposophy is really something of your own or not. If you are going to become an anthroposophist, you have to claim your connection to it through your own decision. For me that took place after I had finished school. I went to work on a biodynamic farm for a year, instead of doing military service in Germany. While I was there, I had time to think, and time to read in the evenings and the early mornings. Gradually, I came to the realization, yes, anthroposophy is something I want for myself. It was even a little bit that I wanted to show my parents and my teachers what it really means to be an anthroposophist…

Then I started at the university and immediately was in groups with other people studying works on physics by Steiner. The work has been quite steady since then.

Question 2 – How is it that you came be the leader of the Sciences Section at Dornach and what does this position involve?

How long do you want this interview to be? [Laughter.] I developed a connection to the Science Section during my time at the university. I had a professor, who was also a friend, who was a member of the Collegium of the Science Section. He often told us about Section activities. While at university, I went to conferences put on by the Section and got to know many of the Section members. When I graduated, I was faced with the question of whether I wanted to continue at the university with a PhD, or do something else. The idea came to me to do some research on a question Steiner suggested relating to the study of the mechanics of the human body. I asked the people at the Science Section if I could do that work there and they said yes, provided we can find the funding, which I did. So I didn’t go for the PhD at that time but developed a deeper connection to the Section.

After working at the Section for a while, I went on to become a Waldorf teacher in high school for physics, chemistry, and mathematics, but I always kept a relationship to the Section. Then the former Section leader wanted to step back because of his age and he had suggested three individuals who might take over from him. The Section members decided that there should be a meeting so everyone could speak about who the next leader should be. As it happens, I got sick and could not attend the meeting. I just couldn’t be part of it. In my absence, they decided they wanted me to take on this role. That’s how it went.

It was an interesting moment in my life. By then I had been a Waldorf teacher for fourteen years and had been feeling that something needed to change in my relationship to the students and to my colleagues. Then this opportunity came up. At that time I had a strong relationship to the Goetheanum mainly because of Jörgen Smit. His work with the Class Lessons had made a great impression on me. He died just before I took on the leadership of the Section. When the Section opportunity arose, I sent him a letter with my thoughts about it. I know he read it before he passed away. That was important to me.

Of course the role is a big responsibility and on the other hand, it raises the question of how to stay human when you take on such a role. How do you organize your work so that you are not occupied only with lectures and conferences but you are able to do creative scientific work yourself? Early on I was not sure if it would be satisfying. When you are a teacher you have students and they need you and you have the feeling they learn something. I was not sure how I would have a similar satisfaction in this position and with this work. And there was the question of my family. How would it be for my children to go to school in Switzerland? That turned out quite well. In fact, I joke with my wife that the deeper karmic reason we went to Dornach was so that my children could find their real teachers. Who knows…

That was 1996, so I have been in the role for some time. It is not a term position but after every five to seven years, I have organized a meeting with Section members and others at the Goetheanum to review my work. In this process, people can speak to me directly or speak in confidence to a person from the Section or from the Goetheanum. This process is not part of the job description but was my own initiative and I think it has been a very good process. The Vorstand [Executive Council] and some other Sections are conducting similar reviews. It is a healthy process. It is important to give oneself a time to consider: should one leave now? Is it time for someone else now? Do I still feel called to serve in this way?

Question 3 – Rudolf Steiner clearly believed that spiritual science is completely compatible with the positive discoveries of natural science but is not compatible with physicalist or materialist reductionism. He also acknowledged that a true reconciling of contemporary sciences and spiritual science would be difficult and would take time. How do you see this work proceeding?

My first thought is that today in science it is almost impossible to speak of a general view. There are so many different views. Perhaps in some realms it is possible to identify what “mainstream” science is, but it is getting harder and harder to do. There are new considerations everywhere. This is even true in physics, for example, beginning with Roger Penrose, and others like him whose thinking is stretching into new areas. At the same time, there are scientists who have stopped thinking in a theoretical way altogether. They even use the famous advice “Shut up and calculate! Don’t think, calculate.” That is not a joke. So there are a wide variety of worldviews at the moment.

It is not so useful to try to convince people that this or that worldview is right. However, it is very important to point out that materialist reductionism is actually dangerous. If we accept this idea, if we act out of this perspective, we actually put the earth and mankind in danger. As anthroposophists we need to contribute to helping people wake up from this.

Let me give you an interesting example of how materialism ensnares people’s thinking. Ten years ago there was a huge movement in Europe of people who were influenced by experiments that Benjamin Libet conducted in the early seventies. He found that in the milliseconds before someone was conscious of a decision, there is a certain signal that can be measured by an electroencephalogram—an EEG. This is the so-called “readiness potential” and based on the existence of this signal, Libet concluded the material cause of a human action comes before the conscious experience of making a decision; and therefore free will is just an illusion. This simplified idea got extensive press in Europe, for example, in Der Spiegel, as proof that free will is an illusion. Some people, for example, Gerhard Roth in Germany, even used this study and follow-ups to suggest we need to change the way we look at responsibility in the justice system. It was all based on very superficial findings and simplistic philosophy but it attracted a great deal of press and public discussion.

Then, a little while later, people were able to show that this “readiness potential” was identical regardless of what decision the person made. It would show up in the EEG in the same way if a test subject, say, decided to place an object on the right or the left. So the readiness potential shows that something is happening in the brain but is not predictive of what the human being decides. This led to other collaborations between psychologists and neurobiologists that are ongoing and open to a wide range of interpretations. Certainly the question of neurobiology and human freedom is far from settled.

Now the problem is that the students in psychology in university today in the first or second semester are still taught, since Libet, that free will is an illusion based on the initial experiments. Here anthroposophists need to take action. My daughter, for example, who is a student at a university in Germany, was quite surprised when we discussed this and I told her about the work that followed Libet’s research and that now other scientists reject Libet’s findings. “But I learned that!” she said. That’s interesting. It is publicity that establishes certain views of the human being. There I see real danger.

Question 4 – In what way is anthroposophy science? What is the same in traditional science and the work of the spiritual scientist?

In both traditional science and in spiritual science, when you describe something to another person, they have to be able to understand it. Both traditional science and spiritual science appeal to our capacity for logical, meaningful thinking.

In traditional science, the effort is made to introduce objectivity to our understanding by quantifying things— by introducing various forms of measurement. So, in addition to understanding an experiment, the other person should be able to repeat it and generate similar values. Gaining this sort of quantitative objectivity is more difficult in areas like human emotions.

For spiritual science, we take a different approach to observation. For example, when Goethe made his study of colors he observed the effect of colors on his soul. The question of wholeness in Goethe’s theory of color—the claim of wholeness—comes up because there are at least six different aspects in his study of color, including both the quantifiable and the non-quantifiable. Wholeness requires these different aspects. But this does not mean sacrificing the comprehensible or the dependable nature of these observations. A spiritual scientist must cultivate the capacity to engage many different perspectives in his work and this process can begin as it did for Goethe before one achieves clairvoyant abilities but this approach— the effort to be wholistic—leads towards this special way of engaging.

Question 5 – It is interesting to consider this idea of comprehensibility. Some of the theories of physics are baffling, for example, the idea time begins with the Big Bang. How can it be that time begins? If science is supposed to explain things, if it is supposed to help us understand the world about us, it seems that in physics the conversation has moved beyond the capacities of the average person. Is it just that the average person can’t keep up or is there something about these ideas of modern physics that is incomprehensible?

That is difficult to answer. The ideas of contemporary physics are produced by specialists so we have to imagine that a certain challenge in comprehension for non-specialists is normal. But, if we take the time to learn about these things, when we review these ideas, we should be able to follow how these ideas developed based on actual observations. If I can’t understand how an idea was developed based on observations, then the idea is at best hypothetical for me.

With respect to the Big Bang, one can follow the steps that led up to this idea. It is complex but it is based, in part, on observations which imply a certain kind of movement of the galaxy. On the other hand, I read an article recently by an astrophysicist in which he claimed that time began 0.05 seconds after the Big Bang. Well, this is funny. Is he just being careless with his words or are we struggling to talk about things that we do not have language for?

Consider how people imagine the Big Bang. They tend to picture that they are at some point in space and from there, they can watch this tremendous explosion. Of course, if the theory of the Big Bang is correct, there could not be any “place” outside the event where an observer could be. Clearly some of the language and ways of picturing things we have from our day-to-day life do not work so well when applied to physics. Interestingly, this does bring us to anthroposophy. The further you go in an effort to understand the Big Bang, the more the ideas resemble what Steiner describes as the emergence of a phase of cosmic evolution out of the dormant state. Things begin with a kind of energy or intensity. It is true the Big Bang may be a sort of materialist counter image but there are aspects of the thoughts of the physicists that shed light on Steiner’s descriptions and vice versa.

There are similar challenges when we try to understand atomic particles. We encounter similar limitations of language and imagination. We know that imagining protons, neutrons, and electrons as little balls flying around is not right. The image of a wave is not much better. It is very hard to imagine something as a potential state. And, as we learn more, if we say that these particles are actually composed of quarks, we are using the word “composed” in a much less solid way than we normally do.

Is it just that these ideas are beyond the capacities of the average person? I think this has more to do with the challenge of applying the language and ways of thinking from the physical world to these realities. It is similar when we try to understand the spiritual in some ways. The way the concepts are given in popular culture may make them almost impossible to understand—that is another matter—but if you take the time to go into these things deeply, if you follow the observations, you see that physicists are led to think about things that are so unlike the everyday that their efforts are in some ways similar to our efforts at striving to understand the spiritual world. This requires the capacity to think into and sit with riddles and mysteries.

Question 6 – Speaking of riddles, how would an anthroposophically-informed physicist answer the question, “What is light?”

Ah, well, I think Goethe was very wise when facing this question. He noted that people go directly after this question, “what is light?” and that this leads to a lot of commentary that is not of much real use. In his unique way, he began by approaching the question from many different aspects, including with his feelings, so that he would eventually come to see color as the deeds and sufferings of light. He realized that he needed to study the manifestations of light in a very wholistic way in order to approach the central phenomena of light itself.

When we begin to think of the manifestations of light there are many aspects of human experience we need to consider. For example, sight is our most important sense. It enables us to perceive over a distance. It provides our orientation in space. In fact, we can speak of space in part thanks to light. These kinds of basic observations lead into physics. What is going on that I can see an object that is far way? We then develop the idea of emissions and absorptions, ideas which belong together. Then we try to understand this connection. Is light made of particles that fly from there to here? When that picture does not work so well, we think about light as a kind of a wave, but there are problems with that formulation as well. The idea that light is both particle and wave is a kind of compromise. So, that is one pathway and physicists continue to work it out.

There is another pathway that begins with a description I like very much: a space filled with light is a space filled with possible images. This shifts our focus to how light works in terms of conveying images. Consider the great cathedral at Chartres. Here we see light fill a space; and because of the design of the windows—only images of saints and holy stories were allowed there—the room is filled with these possible images in a way that evokes religious feelings. What are the special qualities of light that make this possible? I think there is still a lot of work to do to understand these special dimensions of light which cannot be revealed through measurement of photons.

Question 7 – In what sense did Goethe prove the existence of the archetypal plant? What was the exact nature of his experience that enabled him to say, in effect, “Yes, now I have it!” Is that experience something others can repeat? If so, how?

It is important to understand that he was not simply imaging the stages of transformation in a plant in a simplistic way. He was imaging these transformations in great detail based on his observations based on many species. It was out of a deep immersion in this inner work that he came to the idea of the archetype of the plant. It came out of a wealth of experience.

Now it is very interesting to understand this famous conversation Goethe had with Schiller. He relayed his inner experience of having discovered the archetype of the plant to Schiller who said, “Oh, you have had an idea.” Goethe did not accept this at first. For him this meant Schiller was saying it was an abstraction. For him it was a great experience. The point is that Schiller was right provided you understand the term “idea” in an anthroposophical way. A real idea is already a lot! For in the idea, we have contact with the spiritual reality. Goethe came to realize this later. When he writes about the archetype of the animal, he writes that this is the idea of the animal.

So out of experience he came to a real idea. Now is this a proof? I am not sure you can prove an experience. Other people, though, can have the same experience, although perhaps in a different way than Goethe did. To have this experience, though, we have to have work through the stages of metamorphosis in intense inward activity. We experience, so to speak, through our own inwardly plastic activity in a way that is, as Goethe called it, an imitation of nature. If we can do this, we come to the point where we experience the archetypal plant.

We can think of mathematics here. You can write down a proof but each person has to work it through in their own thinking to have the insight and see that it is true. When you work with students you watch this process over and over again. They have to become inwardly active to understand something. Everyone has to find the reality of such things in themselves. This is the way with Goethe’s great discovery.

Question 8 – It seems to me that the laws of inorganic chemistry are very well developed. If this is the case, why can scientists not chart a path from the inorganic to the organic and duplicate this process in the laboratory? Why can’t scientists create life?

Well, we have been able to create organic substances artificially for some time and what you say about inorganic chemistry is also true to a certain degree in organic chemistry which is also highly developed.

But to address your question, we need to consider first what we mean when we say something is alive, or to say that something is an organism. Clearly an organism is something far beyond just a complex substance. When we try to characterize living entities we find that they have context they require and that they are formed out of dynamic polarities. Even the simplest single cellular organisms are highly complex. So if we try to understand the cause and effect relationships in these simplest of living beings, we are already in a vastly complex system and this complexity includes how they interact with the environment. For example, it is very difficult to even distinguish the simplest organisms from one another under a microscope. In order to do this, you need to put them under different conditions and watch how they interact with the environment. They are distinguished by their metabolism, not their shape.

If we want to understand living beings we need to think more about this relationship to the environment. That is a big clue. Materialistic approaches tend to look for ways in which things can be built up from simple elements. I am suspicious of this building block approach. I do not think we can understand the emergence of life in this building block way.

Rudolf Steiner’s conception of evolution is quite different. Current evolutionary theory sees the human being as, one might say, an end product of evolution. For Steiner, evolution begins with the human being, although not in the form that we are in now. Humanity descends from the spiritual world and undergoes a process of gradual densification and then new experiences in material life. This is a completely different way of understanding how highly complex organisms emerge and are then subject to environmental impacts.

Question 9 – Can you tell us something of your current research? What sorts of questions are you trying to answer?

Now as you can imagine working for the Goetheanum, the Section and our small institute there is only limited time for research. On the other hand I need to try to be productive in a way. So now I am:

1. Working with the literature for a new project on how to understand quantum physics from a Goetheanistic and anthroposophic perspective and how to bring that in the physics curriculum of Waldorf schools.

2. Following the most important literature on some ecological impacts like nuclear energy and electromagnetic waves.

3. And last but not least, there is my ongoing interest and love for light and color, Goethe’s approach and the atmospheric colors like rainbows, halos, aureoles, and so on. Currently I am working on the English translation of my book about these.

Question 10 – Is there anyone in the anthroposophical movement who has been able to follow the path through to becoming clairvoyant?

Well, no, not like Rudolf Steiner. Not that I know of. I do not think anyone has followed the anthroposophical path and gotten so far as achieving the disciplined, exact clairvoyance that I believe Rudolf Steiner possessed. But there are many people who have had various degrees of achievement. Some of these experiences seem to me to be of a more personal significance, and less about pursuing the organized approach to the path. Others though come more directly out of the path of training that Rudolf Steiner presented in such detail. A good number of my colleagues report such experiences. I try to listen carefully to their descriptions. Most of these have to do with imaginative cognition and with the etheric realm. Sometimes they speak of experiences with elemental beings. I know some of these people very well and they are serious, careful people, so in general I trust these reports. When it comes to more dramatic reports such as those by Judith von Halle, I think this more a matter of individual destiny. She herself says if one wants to develop as a spiritual scientist one should follow the rigorous path that Steiner described. So I am okay with that.

A last point on this would be to note that over the last few decades, I hear more credible instances of children reporting supersensible experiences to Waldorf teachers. So, of course, there may be bias here but it may also be that those sorts of experiences will become more common over time as Rudolf Steiner suggested they could if we meet this in our children in the right way.

Robert McKay is an anthroposophist, psychotherapist, and philosopher who lives in Toronto, Canada. He is working on a book exploring the transformative power of anthroposophy for the self and society.