13 minute read

HER LIFE WAS ART

from Grotonian Draft

by Amy Ma

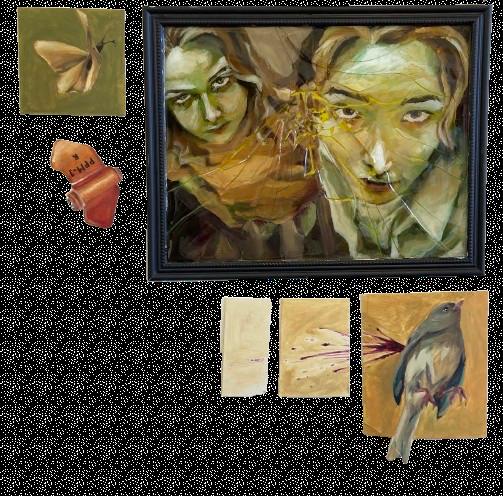

Alisa Gulyansky

June Lancaster embodies tragically the downfall of the overworked y2k child star. Of course, with the exception that she never was a child star -- or a star at all, for that matter -- and never resurfaced in tabloids after her unwieldy nosedive-from-grace. She merely synergized that energy: the aura of the once-famous lunatic, relevant not of her volition but by the highly invisible and inexplicable threads of Nostalgia and Time.

Advertisement

As with most child stars, June began her descent into the endless chasm of existential dread around the time of her fifteenth birthday. The story goes that she fell into some sort of emotional abyss after her parents died in a car wreck and she was sent to live with her estranged uncle. Though, come to think of it, I’ve also heard the version that nothing actually happened to her family, and she just took the depression upon herself.

It hardly matters. She became depressed -- not cripplingly so, but enough to forget how her own emotions used to feel for some time. So when she finally got treated years later, she’s said to have experienced this total awakening: some sort of cerebrally, sexually, emotionally electric catharsis.

At this time June lived with four roommates so she could afford rent in the city. She worked for some low-level photography business uptown, and everyone who met her had a perfectly consonant image of June in their minds: precocious in thought, eccentric, but dutifully so, and positively insufferable.

Taking her emotions upon herself in greater doses than she had ever borne, everything was suddenly beautiful: the color of the sunset and the color of cement, her roommates’ snores, the aroma of fresh laundry on a Sunday morning -- none of it could go undocumented.

Her spiritual awakening landed her on the corner of 53rd and Crook where she bought a video recorder that looked as if it had survived several car crashes.

“Today is Saturday, the 27th of April,” she says in her first video entry. She wears a red beret and stands in her kitchen while her roommates make stir fry. “This is Arya,” she smiles, staring at the woman stirring a pot of some brown sauce. Arya looks over with a smirk.

“Hi, June’s Camera,” she teases.

“Hi, June’s Camera,” her three other roommates echo somewhere in the background of the tape.

The scene was perfectly nostalgic. It was the kind of thing you see in a wistful compilation someone makes of their youth, garnished with vintage filters and strategically outdated music. June knew this. She felt, filming it, as though she were watching it vicariously through herself twenty years into the future, reminiscing on her early years as she would become an exemplar of wasted potential and dying youth.

She watched back the recording of the scene in the kitchen when she was in her bedroom and began to cry. It was beautiful.

And so, June was happy. Not because she lived with four other twenty-something year olds, or that she had a steady job, or because she loved them or the job or the city, but because it all amounted to some glorious abstraction of Art; her life was art and she was happy.

June continued to film her roommates cooking. She would rejoice especially when her roommates would spontaneously break into dance in the kitchen like they do in any heartwarmingly cliché film about your twenties. And when cooking would erupt into shouting in the corridor, June would sneak into the kitchen and poise the camera in such a clandestine manner that she would capture the very fervor of her roommates’ altercation. She reveled at how innately human her roommates were in just their everyday interactions. They cried, laughed, argued, danced, loved, and hated -- so gloriously did they represent the human condition, June thought.

So June locked herself in her bedroom every night, piecing these incongruous scenes into some bombastic ballade of the fire that is youth. Lingering upon the threshold between exemplifying the monotonous nature of her existence and enforcing the cliché that there would be beauty in everything, her film was beautifully confused.

June entered Portrait of Some Youth into a local short film festival and won second prize. She was featured in a minor article in the paper and a couple local agents conveyed their congratulations, though June heeded none of it. She was an artist now.

In several months’ time, June fell madly in love with a woman named Rosemary who visited her office twice weekly to pick up headshots for her modeling business. June found it poetic that her name was June and the woman’s name was Rosemary, and rosemary flowers in June. By some cosmic twist of fate, Rosemary was sent to June to become her own.

The following week, June inserted a piece of paper between prints asking Rosemary to coffee, hiding her camera atop the equipment shelf and documenting the entire interaction. To her surprise, the next day when June went to pick up her mid-afternoon coffee, she found Rosemary waiting for her.

“I asked around,” Rosemary said grinning.

And so June and Rosemary talked all afternoon. They discussed the Renaissance, poetry, film, the nature of love -- the kind of seemingly banal subjects any half-witted intellectual would use to try and impress someone they’re interested in. June hardly cared for the words coming out of Rosemary’s mouth, just that they sounded poetic and horribly beautiful.

June asked Rosemary if she could record their conversation with her camcorder. Rosemary, a poet struggling to get her work published in even the most overlooked of journals, immediately agreed. She thought this could be her ticket to unlocking some true art behind life, so human as it was, that she had been so removed from in her time as a poet.

June would help her understand.

A tape I’d found from a few weeks after this time takes place in what seems to be Rosemary’s childhood bedroom. It begins in the middle of a scene that had started before June remembered to turn the camera on. It is edited in such a way that makes it seem unnaturally authentic.

Rosemary’s expression is that of mild discomfort though she continues her monologue from before the camera was recording about all the memories she had made in that old room. June places the camera on a shelf and tells her to ignore it. She then proceeds to call Rosemary beautiful. Rosemary feigns a smile.

June says she’s sorry if the camera makes Rosemary uncomfortable and Rosemary says it doesn’t. June pretends to turn it off but doesn’t. She and Rosemary embrace. Rosemary shows June her diary from when she was sixteen, chock-full of half-baked poetry so powerfully reminiscent of the naivety of the adolescent mind.

June tells her her mind is perfect and Rosemary brushes it off. June looks Rosemary in the eye and tells her she really means it.

Watching this for the first time, I was expecting something to happen. Expecting them to kiss or reveal their love for each other or at least just hold each other’s hand in some kind of mutual understanding of their love. But all that happens is that Rosemary laughs and says, “You’re a great friend, June. You really are.”

June turns her back to Rosemary to show the camera her artfully wistful expression and hide it from Rosemary. June sniffles and Rosemary asks if she’s okay. June responds that her mother is dying. They embrace.

III.

Rosemary’s Room won the 12th annual Fischer Prize for Best Short Film in the state. June was invited to celebrate at nearly every gay club in the city, and gave a speech at a local art museum. Yet, despite the minimal press and local acclaim, June figured she could hide this from Rosemary for long enough that the buzz surrounding the prize would eventually subside. Some things, June resolved, Rosemary hardly needed to know.

That weekend, in efforts to distract Rosemary from the omnipresent reminders of her awkward success, June invited Rosemary to go clubbing with her.

Of course, this, too, had been calculated on June’s behalf. The entire weekend, June made sure not to have a single sip of alcohol – that way, she would be able to nurse a drunken Rosemary back to health when she could hardly stand or see the faces in front of her.

Her prediction came true. On Sunday night, June dragged a half-conscious Rosemary from the bar to her Prius. Rosemary vomited profusely in her arms and told her she had magnificent brown eyes. On the car ride back to Rosemary’s place, June stroked her hair from behind the wheel and told her everything would be okay when Rosemary began to cry.

Glancing at the intoxicated mess of Rosemary sprawled across the passenger seat, June swelled with such intense adoration for Rosemary she could hardly breathe.

Rosemary, this glorious jewel of a woman, was in every way, hers.

June recorded the drunken car ride home with a camera she’d set up in the backseat of her car and edited the footage at Rosemary’s apartment until dawn. The product was positively enthralling: all captured in ten minutes’ time, it managed to piece together seemingly meaningless clips from parking lots and nightclubs, subway passengers, and homeless alcoholics into an indulgent, eternal treatise of love in the 21st century.

When Rosemary heard the news that June was submitting her film to international festivals, she dialed June’s number and screamed into the receiver before June could even answer the phone. She told June that she had no right to submit footage of her in her most vulnerable moments and without her consent, to be exploited and neglected and treated as hardly human. When June told her that she filmed her precisely because she was so human, Rosemary told her she was the phoniest person she’d ever met and promptly hung up.

June took Rosemary’s exit horrifically, all things considered.

Of course, as June sat staring at her ceiling for hours each night, the last person she could think of to blame was herself.

At first, it was Rosemary’s fault.

Rosemary’s fault for failing to understand what art was, who June was, why art couldn’t be exploitative if it managed to so elegantly spin life’s dramas into something outspoken and remarkable. June’s films were the most endearing thing she could have possibly dedicated her love towards, and now Rosemary would never be able to understand that love is nothing without art.

But as her contempt for Rosemary dwindled through the weeks she spent mulling over Rosemary’s shortcomings, June slowly began to realize that she had nobody left to shift her blame towards. The longer she locked herself in her room, the more dust that collected on the box encasing her camcorder, June was left increasingly with no choice but to open her merciless door to Guilt.

June could hardly face the idea that she had destroyed her own relationship just by combining the two things she loved most: Rosemary, and art. To fail to convey the meaning of her entire being to a woman she prized more than any trophy or medallion was to fail as a human being – and even more, as an artist.

June needed to make Rosemary understand her. She would have to find a way to compensate –overcompensate – for the betrayal Rosemary had endured. She would have to prove to her that art could be more than an exploit or absent-minded centerpiece. And Rosemary would have to be moved, swayed beyond her own will, shown that June’s art sought to unearth beauty and meaning, rather than to desecrate it.

That had been all she wanted to do for Rosemary. To show everyone how beautiful Rosemary was and how inextricable her beauty was to the very fabric of the universe. To show her that she was art. That her life was art.

Through days of blank contemplation and bitter respite, she realized what she’d have to do.

June would have to return to the only artistic device she had evaded for so long in her artistic pursuits – something artists seldom dare to explore. Rosemary would be left with no choice but to absorb June’s inventions, viscerally, and digest without willing to. If emotion alone failed to show Rosemary the meaning in her art, June was left with no other option but to appeal to Rosemary’s most primal human senses: the carnal, the visceral -- the disgusting. Art would be something that is not cherry-picked. Art would be Rosemary, and art would be death.

As soon as June realized what her art would have to become, she was struck with an energy she had never before endured. It was as if her quest for this meaning were a race, some sort of diabolical 100 meter dash to prove to everybody that her years of intellectual mania had truly been worthwhile. That one day, she would wake up and become the Buddha reincarnated, enlightened in the ways of life and overflowing with such expansive knowledge and art.

June stopped sleeping. She was determined to film everything, camera following her at each waking moment: to the bathroom, in her bedroom, roommates sleeping, drunken men screaming at one another in the street, strip clubs and overdoses, hospital beds and car crashes -- gone were the days when she would cherry-pick the meaning of art. During the day, June invited an array of houseguests -- acquaintances from her office, bars, the subway, the street -- to interview them. She would film their every move, visceral reaction, murmur under their breath -- and when they finally stormed out from the sheer discomfort of her interrogation, she would delight in the surplus of emotions she was able to so authentically capture.

She took it upon herself to invade the very sanctity of human dignity, all for the sake of research and for the sake of art.

When she did sleep, she slept in the late afternoons when her mind grew heavy and her sanity was too distant to touch. Her dreams seldom strayed from reality. They were like her own films, mesmerizingly idiotic and complex beyond all knowledge. Sometimes she would awake from her restlessness and exclaim, “Oh, the beauty of it all!”, scribble something onto a piece of paper, and fall back to sleep.

But June was unsatisfied. No matter what she collected, nothing seemed to be meaningful enough, to possess enough poetic power to really sway anybody. She would need something more. Something jarring and horribly graphic that could make children cry and adults fall to their knees.

And one day the meaninglessness of it all seemed to wash over June all at once, pounding its fists at her until she would be left no choice but to act. To go out into the world and find some semblance of meaning to complete her cinematic trash-pile.

All of a sudden, June ran out of her room, slamming the door behind her, and ran outside her apartment for the first time in weeks. The ground was glazed over with rain and wind billowing faster than she could move. She wore few clothes to cover her body; her eyes were bloodshot from not having slept in days; and her hands were shriveled to a near pulp from the times she would wring them against her desk in frustration. But when she emerged, she found nothing nearly good enough to satisfy the great existential quest for meaning she had undertaken.

So as soon as she felt a droplet of rain fall upon her face, June let out a devastating sob, crumbling to the ground and shrieking just loudly enough to tune out the faint murmur of some red-speckled blur slithering toward her.

But it seemed to call to her, hissing ceaselessly and tantalizing June until finally, she sprung back up, eyelids pinned to her forehead and hands shaking behind her camera. Before her glistening eyes crept a snake the length of her torso making its way toward a small rodent -- perhaps a bystanding mouse -- cautiously preparing its attack. June grinned.

This was exactly what she needed for her film -- a harrowing tragedy of the food chain and its victors; the old-age parable of life and loss -- the human experience in its most simple form. Of course, if she could understand the crux of animal nature, June would subsequently understand the underpinnings of what made humans so human: their visceral, animal existences. Here lay the meaning of art – here lay the remaining piece to her puzzle for Rosemary to understand her art, wholly, viscerally.

June grabbed a plank of wood that lay several feet away from her accompanying some nearby renovation project and swung it around her shoulder. She edged quietly towards the prospect of artistic infamy.

The snake was now hovering above the mouse, still uncertain as to how to consume its prey.

“Eat him!” she shouted fearfully, wielding the wood above her head like a whip. She tapped the screen of her camera vigorously as if it would cause images of the snake eating the mouse to materialize on-screen.

But the snake did not move, seeming even to back away from the mouse as if June’s encouragement spoiled his appetite.

“Eat him, I said!”

The snake slithered away from the mouse and toward June.

If the food chain didn’t work as it was supposed to, June thought, she would have to force it to. Her hand swiftly approached the head of the snake and in one fell swoop, she beat it with the wilted pulp of wood.

The snake coiled back, its tongue barely grazing the glass of June’s camera.

“EAT!”

She mustered as she struggled to heave the wooden plank behind her.

“HIM!”

She launched the wood at the snake, gazing starry-eyed as it skidded backward.

After several seconds, the snake regained strength and began to accelerate once more into the direction of June and the mouse. She clutched her camera at her side, heart pounding lifelessly against her chest: she would be a legend -- a god, even.

And gods never die; never wither; never cower in fear like the stupid mouse that lay motionless on the asphalt –

But the snake came nowhere near June and her silly camera – and somehow, neither would the mouse. They simply lay where they were, plastered to the ground by some invisible force not even June could manage to defeat.

The three of them stood, motionless, daring to stay on that street corner for a lifetime. But soon, the clouds began to swallow what remained of the sun and the pair slowly crept away, leaving June with nothing in her hands but a morsel of some dream ill-spent.