26 minute read

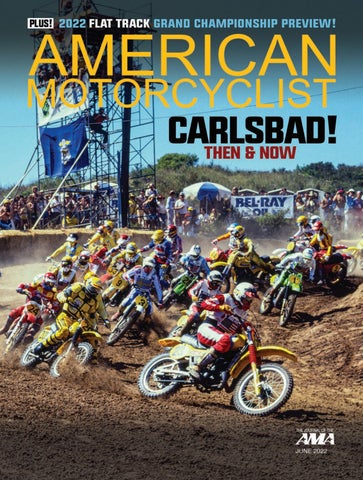

COVER STORY CARLSBAD — THEN AND NOW

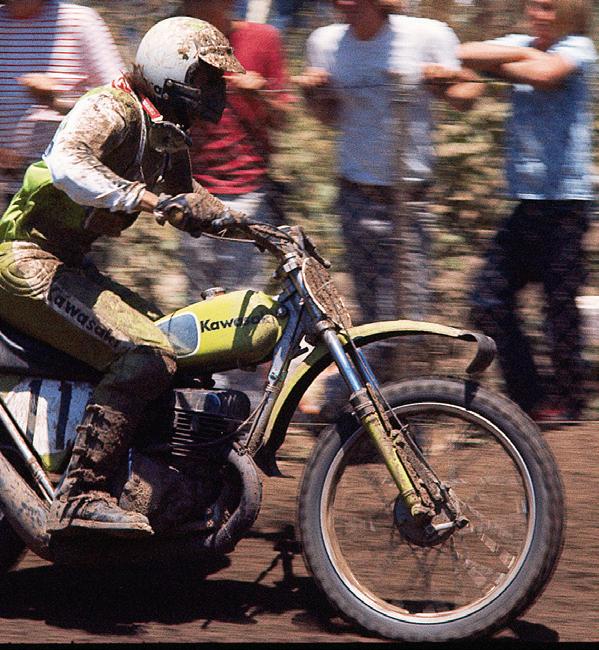

Turn one at Carlsbad, today and back in the day. That inside berm hasn’t changed much at all.

SACRED GROUND

BY MITCH BOEHM / PHOTOS: JOE BONNELLO, SCOTT COX, DAVID DEWHURST

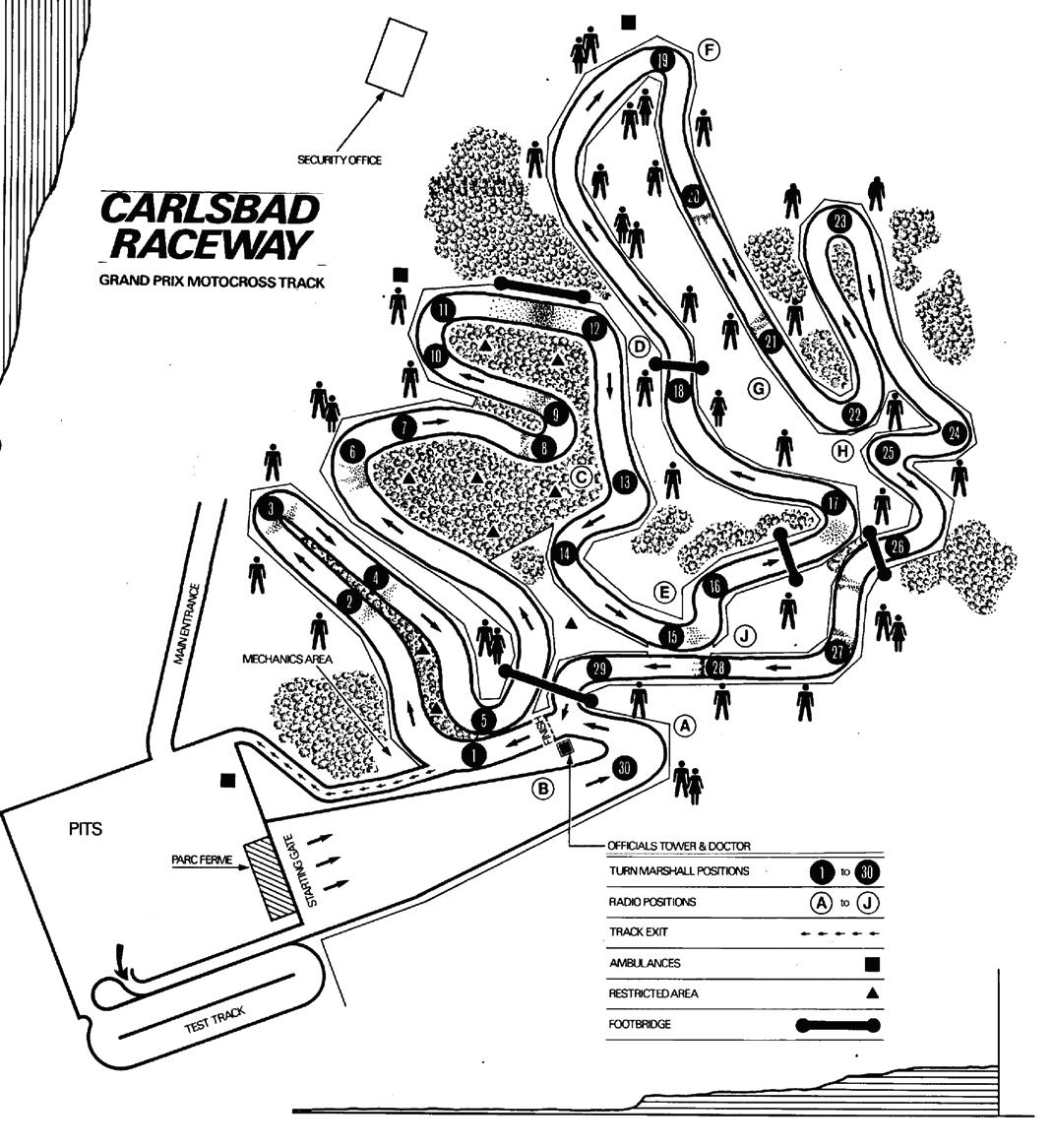

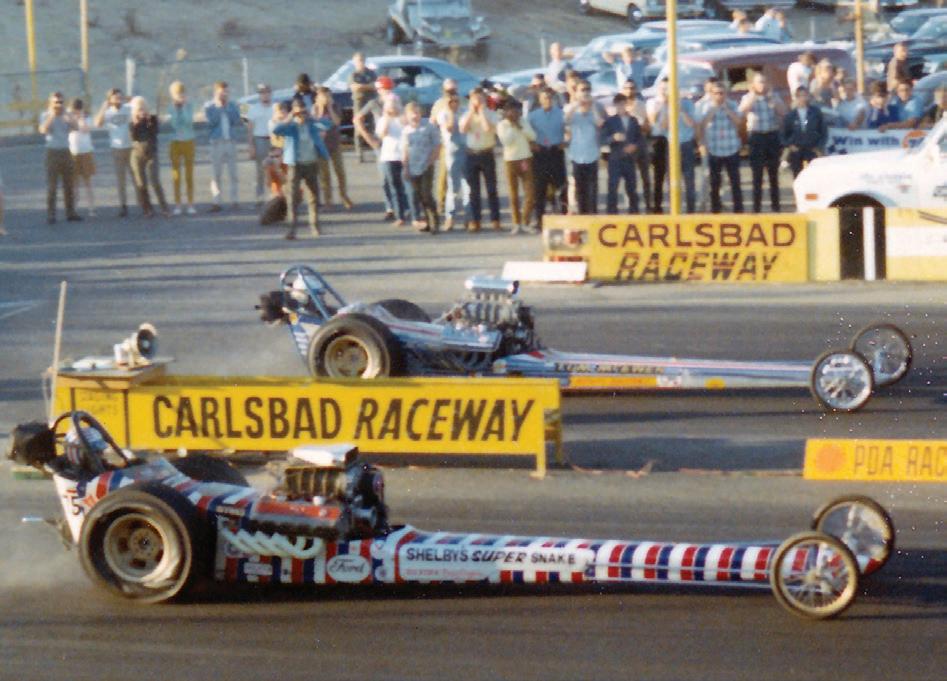

If you’ve not been there recently or had someone point out what’s where, it’s hard to get your bearings — even if you raced there or attended one of those legendary 500cc USGP races back in the day or watched on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Too much of California’s Carlsbad Raceway is gone, too many acres surrounding the most famous motorsports canyon in motorcycling — including the renowned dragstrip — have been transformed into boring, businesspark real estate.

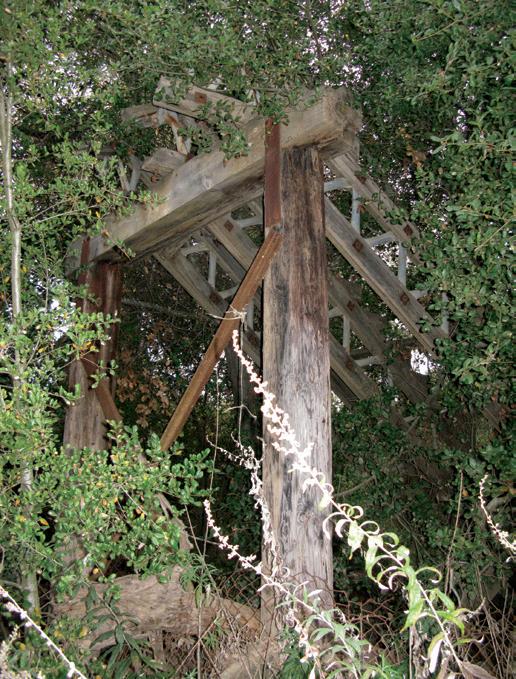

But once you know what’s where, or wind your way down into the dusty arroyo and catch a glimpse of the legendary starting area or still-intact Devil’s Drop jump, or come face-to-face with the ruins of the last remaining spectator bridge that’s now covered by so much foliage it looks like some industrial rain-forest relic from a science fiction flick, it happens… Carlsbad, arguably the most notorious motocross circuit in American history (1964-2004), is no more. But sections of the legendary track still exist, and the place remains powerfully emotional — and is set to finally get the memorial it deserves.

A heavy historical pressure settles on your shoulders like some massive, ’70s-spec Hallman chest protector, a realization that you are standing in a very special place… precious acres of mud, adobe and weeds that impacted the sport of motocross more than any other in the U.S., and maybe even the world.

Suddenly, you can see and hear Gerrit Wolsink’s Suzuki, Brad Lackey’s Kawasaki, Marty Smith’s fire engine-red Honda, Marty Moates’s Yamaha, Kent Howerton’s Husky or Steve Stackable’s Maico ripping — Rrrrrraaaaaaaaaaa! — up and then down the terrifyingly rough Carlsbad Freeway. You can see and hear the deafening roar of thousands of shirtless, sun- and beerdrenched fans screaming and waving American flags as their heroes flew by, usually on the edge of control as Carlsbad’s concrete-hard whoops threatened to explode

their wheels or suspension and vault them into the snow fencing.

Standing there among the dirt, weeds and broken bits of ’70s and ’80s sponsor signage, the quiet broken only by the sounds of birds chirping and frogs barking from the very pond promoters and track owners sucked their trackwater from, it’s hard to imagine that so much motocross history happened right here — the races big and small, international and local, the famous and not-so-famous riders, the TV coverage on Wide World Of Sports, the TV helicopters flying overhead during the race, and the many thousands of crazed fans that turned out each year.

But it did. And in a thoroughly epic manner.

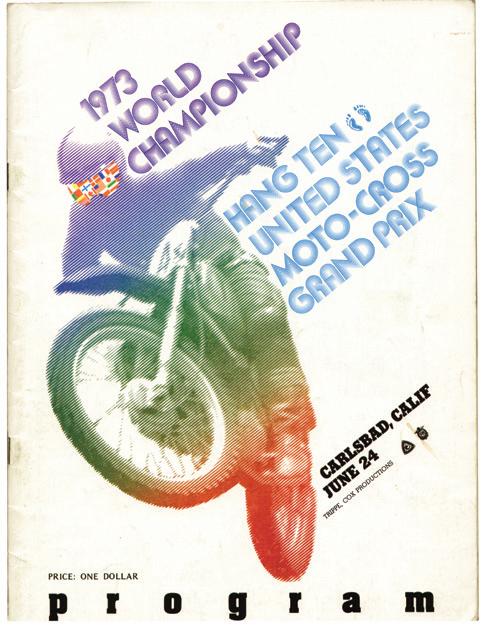

For 14 years, from 1973 to 1986, Carlsbad was ground zero for international Grand Prix motocross, a sunbaked mecca for riders, factory teams and spectators,

The first USGP, circa 1973. Things were crowded and crazy right from the beginning.

This page: Recent shots of the most legendary motocross venue in America. It’s eerie to go there now. Opposite: The late Carlsbad USGP and Superbikers promoter Gavin Trippe, crossing up on Devil’s Drop.

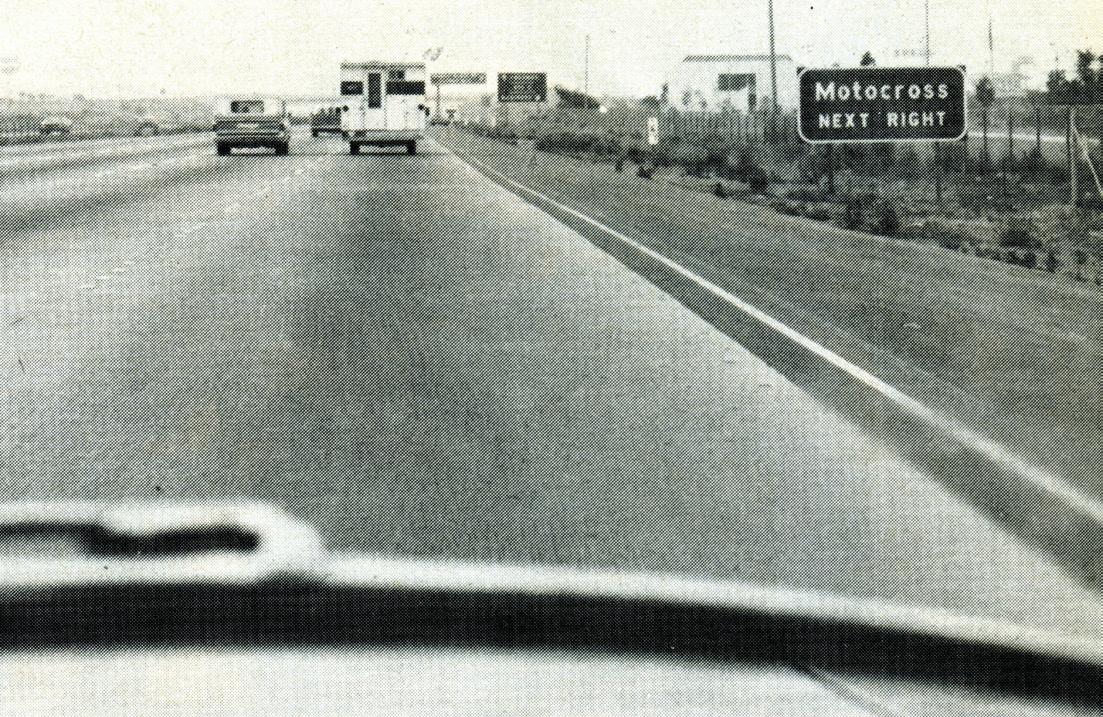

all of whom made the trek to San Diego county each summer to see what quickly became the event to see in the motocross world. There was even a DOT-approved “Motocross Next Right” sign on the San Diego Freeway to help folks find their way. All of which explains why Carlsbad will be revered forever by motorcycle fans the world over.

“It’s still an amazing place,” the late AMA Hall of Famer Gavin Trippe, long-time Carlsbad USGP promoter, told me years ago as we walked parts of the track, “and coming here now is a time-warp, a step back in time. I was heading up Interstate 5 on New Year’s Day in 2007, just after Marty Moates [1980 USGP winner –Ed.] so sadly died, and I stopped by the track. Hadn’t been there in years, and no one was around. I walked down into the wash and got lost in time, lost in thought. All of it came welling up. Not just the Grand Prix and Superbikers events themselves, but all the people, the crowds, the racers, the deals I made, the utter craziness of it all. When I look back on it I almost can’t believe it all actually happened.” Growing up in Ohio and not moving to California until the mid-1980s, I only attended one big-time Carlsbad race — the ’85 Superbikers. I remember being wowed by the place in a macro sense, but since the Superbikers event was spread out all over the property (and very little of the motocross course was used), I never got much of a feel for the legendary circuit I’d seen on TV and in the pages of Motocross Action, Dirt Bike and Popular Cycling. I raced a handful of local Grand Prixs there in the latter 1980s and early 1990s. None were proper motocross meets, although they did use about a quarter of the International circuit, including a couple of the nasty uphill/downhills, which were pockmarked with ugly, square-edged whoops. So I did get a bit of the flavor of the infamous “Carlsbad Freeway,” albeit at a much slower pace.

That hillside section on the circuit’s southern border, the whooped-out uphill and downhill parts we watched

GAVIN TRIPPE

AMA Hall of Famers Roger DeCoster, Broc Glover, Heikki Mikkola, as well as Hakan Carlquist and others rip up and down at such frightening speeds, is now occupied by a business park. What’s left now is the northern and western section of the course — the starting area, straightaways and turns in the lowest part of the canyon. About a third of the original track remains, some of it walkable, with other sections buried beneath overgrowth.

Carlsbad’s motocross track was originally laid out by AMA HOFer and CMC’s Stu Peters and Kelvin Franks in the mid-1960s. “They laid out the bottom part after they’d come back from Europe and decided to put on races,” Trippe told me. “In the late ’60s I took that basic layout and added to it. Every year we’d lengthen the loops as the races got bigger; we’d sit around, draw it up on a scrap of paper and build it. Larry [Grismer, the track owner] and his kids would help. As a motocross journalist in Europe covering the GPs, I’d been to every major MX track in Europe, so I knew how things should be.”

Jeff Grismer [son of Larry] remembers some of the changes thusly: “In the latter ’70s, Roger [DeCoster] came to my dad and me to brainstorm ways to make as much of the track multi-lined as possible. In one section we came up with the idea of making the outside line into a sweeping banked turn with a bump on the shorter, inside line. We built it using a tractor and Roger tested it. We found it opened up the track nicely, and we implemented the idea throughout the track in the years to come to help keep things exciting.”

One of Trippe’s early successes was convincing the city of Carlsbad to allow the race in the first place. “When we did the first big race [the first of two Trans-AMA races, in ’71 and ’72, to prove to the FIM they could pull it off –Ed.] I had to meet with city managers,” says Trippe. “I told them we’d have riders from all over the world, and one of them asked me how the riders were gonna ride their bikes here from Europe! They had no concept what we were doing. But once it started they became very supportive and proactive. We helped put Carlsbad on the map. Once

the USGP got big, President Ronald Reagan sent me a letter of commendation, and the state put a ‘Motocross Next Right’ sign on Interstate 5. Can you imagine that happening today?”

A decade or so ago I visited Carlsbad one afternoon in mid-November with motorsports photographer Joe Bonnello and industry marketing veteran Scott Cox. Both grew up near Carlsbad, attending the big races and competing in local race meetings there. I expected them to be moved by the visit, and as we wound our way into the shallow valley I wasn’t disappointed.

“It’s just amazing to be here,” grinned Bonnello, who was vibrating like a puppy as we walked down the start

straight toward Turn 1. “Once you figure out where things are, it all comes flooding back.” Cox, who’d visited a few months prior, seemed every bit as excited. “Can you believe,” he asked rhetorically as we arrived at Turn 1, “that we’re standing in Turn One at Carlsbad? It’s a mindbender!”

It was. The large, chest-high berm on the corner’s inside was there in all its glory, and when we climbed it we found the cement and steel footings of the legendary white tower that dominated the inside apex. As we snapped photos, Cox spied a bit of red material sticking out of the ground, and when we yanked it out we found ourselves holding a 15-foot Yamaha International banner, which Cox and Bonnello said was from the early ’80s. Amazing.

I often use the term “moto-archaeology” to explain what we’re doing with American Motorcyclist, and digging up that banner — and uncovering the remnants of a large Suzuki sign later on that day — was a perfect example.

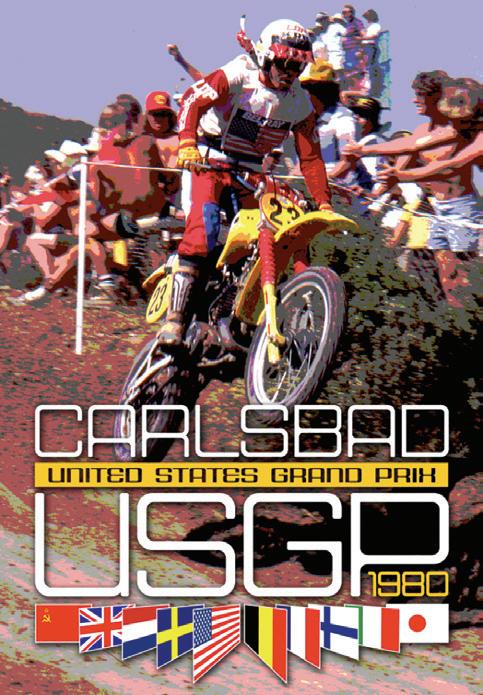

We then walked 100 or so feet southwest and found ourselves standing atop the “drop off,” which ABC’s Jim McKay, Sam Posey and Jim Lampley called “Devil’s Drop” during all those famous ABC telecasts. I’d seen so many legendary photos shot here, including the classic one of Marty Moates with his left fist in the air as he won the 1980 USGP, the first win ever by an American.

We headed a bit farther south into the scrub and

The Carlsbad USGP was a big production, for racers (that’s Roger DeCoster being interviewed at left), for TV techs and for fans, who packed in around turn one, Devil’s Drop (above) and the rest of the venue like sardines.

The Carlsbad Freeway uphill (inset) and downhill (main image) separated the men from the boys, and was brutal on machinery, too. Only one of the five bridges remains (above right), though today it’s nearly totally covered by vegetation.

overgrowth, checking out several of those feet-high outer berms surrounding the corners we’d seen in so many magazine articles and on TV, jabbering about this pass or that crash we’d seen there — including that crazy, finalturn finish in ’74 with Wolsink and Mikkola where Wolsink slammed into the earthen wall so hard he crashed, though luckily after the finish line.

We’d heard that parts of one of the spectator bridges still existed, though we could see no sign of it from our vantage point. We split up to see what was hidden in the dense brush, and a minute or two later I heard Bonnello yell, “The bridge! I found it!”

It was a surreal moment. Walking up to the massive telephone poles jammed into the ground and seeing the spans laying nearby and the trees dwarfing the entire structure, I felt as if we’d found a long-lost civilization, one that burned brightly for a decade or two and then fell suddenly silent. This bridge was located between turns 16 and 17 on a part of the track that routed riders back up toward the track’s major uphill/downhill section — known to many as the Carlsbad Freeway.

None of us said much for a few moments; we just walked around silently, shooting pictures and checking out the path of the original track — still visible — running beneath the bridge. “If I close my eyes,” Bonnello said, “I can feel myself walking over this very bridge 20 years ago, with thousands of cheering spectators on either side of me, and bikes ripping by below. What a crazy scene!”

Cox just smiled and said this: “We are standing at what was — and maybe still is — American motocross’s ground zero, fellas.”

No doubt about it.

“We built five bridges in all,” Trippe told me, “and that’s the only one they didn’t tear down. It was apparent from the early races that, while you can put up fences, you can’t keep folks from tearing them down or jumping over them. So we built bridges using used telephone poles and old housing joists. They’d never pass inspection now! At first, folks stood on the bridges and watched the race. But that was an accident waiting to happen, so I boarded up the sides and eventually put signage on them, which became a huge revenue stream.”

I asked Trippe about the track itself and how it was viewed — knowing full well many riders thought its mud-in-the-morning and cement-hard-whoops-and-blue-

groove-by-afternoon were hellish beyond description. “It was definitely gnarly,” he said, “especially in the beginning, when the bikes only had five or six inches of travel in back and maybe eight up front. The guys took a terrible beating; it was a tough, tough track. But everyone had to ride it, so it really showed who was in shape.”

“I remember we had posts on the sides of the ‘freeway’ downhill that were maybe 20 feet apart,” he added. “Early on they’d clear maybe two of them launching off the top. But in later years, as the bikes got more suspension travel, Mikkola did four or more, which would be 80 or 90 feet. Amazing! The track really did, over the years, have the ability to chart the evolution of the motocross bike,

especially in the suspension department.”

From there we circled back toward the starting area and spied the pond that supplied water for the track’s sprinkler system. “We couldn’t use a water truck,” Trippe said with a laugh, “cause if it ever rolled down one of the hill sections it would have killed 100 people. God knows what’s buried in that pond!”

“It’s amazing to think about it now,” Trippe added, “but I can’t believe I did what I did all those years ago. It was so risky. But I was young and fearless, and when you’re young you don’t consider consequences. During the races I could never sit still, never watch. It was like a grenade was about to go off. Even when Moates won, I could barely watch. I could hear the crowd and knew what was happening. Here I was, with the FIM watching, a load of international racers who’ve flown there and who depended on the World Championship for their livelihoods, and we had a bazillion crazy fans, which meant any one of a hundred wild disasters could happen.”

“And there were miles of TV cable and hundreds of thousands of dollars of TV equipment…so I was always a bag of nerves. I’d walk around the place the day after and swear I’d never do it again. But you know what? We never had an insurance claim. Never got sued. Never had to sue anyone. It wasn’t like today, when you walk into a stadium

GERRIT WOLSINK

ROGER DECOSTER

that’s ready for the event; we were totally on our own then. Crazy, crazy times.”

But good times, too. Very good times. “We never missed the USGP at Carlsbad,” says longtime So Cal racer and enthusiast Alex Judd. “We’d stand on the hillside and watch DeCoster and Wolsink come ripping down so close to the fence that if you stuck a popsicle stick through the fence they’d pick it off. We looked at each other and just shook our heads…amazing!”

Riders had strong opinions about the place, and strong memories, too.

“It was a concrete hell,” the late Team Yamaha’s Mike Bell told me, “but what a great hell. Carlsbad was a magical place; there are so many memories. It’s ironic that we hated the place when we had it, just like Saddleback. But now that it’s gone we’re all sad and nostalgic. Like most things in life you don’t know what you have ’til it’s gone!”

“I always liked going to Carlsbad and the challenge of trying to win it,” five-time World Champion Roger DeCoster told Motocross Action’s Zap Espinoza for a

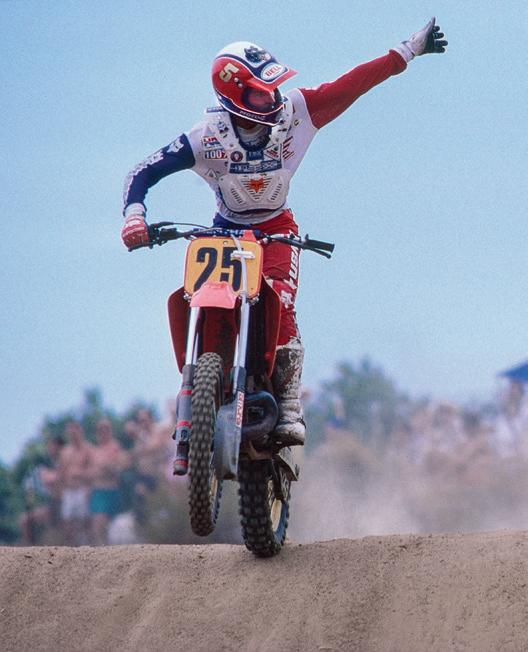

DAVID BAILEY

Carlsbad story Zap wrote in 2018, “but it never worked out, some because of bad luck and some by my screw-ups. I think I had too many distractions from my desire to help to promote the race. [Also], I think I set my bike up to work well in practice and not enough for how the track ended up by race time.”

“By comparison,” DeCoster added, “my Suzuki teammate Gerrit Wolsink hung out at Gavin Trippe’s house, out by the pool having a good time. He was totally relaxed and rode around at an average pace. By the end of the day, anyone who was faster than Gerrit and really tried to win would mess up. Gerrit got the overall win five times because he had Carlsbad figured out!”

“I liked California very much, the weather, the people and the track,” five-time Carlsbad winner Wolsink told Zap. “The layout was very interesting, and I thought the way the track conditions changed during the day was good, too. To go fast at Carlsbad you had to have a fluid style, not stop-and-go. [In] 1974 I hung out with Gavin Trippe. It was a lot of fun, [and] I think it helped me for the race by taking my mind off it a bit. Roger was always too busy with all his commitments and had so much stuff on his mind that I think it hurt his effort.”

“A tactic I used at Carlsbad was to find a spot on the track where I could relax, take a breath and then go hard again. I even practiced that in my training. My secret for

Carlsbad was brutally rough, with rock-hard whoops that never got graded flat. It was also slick as ice in places, especially in the morning. It rained and was very muddy in ’82; Danny McGoo Chandler won, joking, “I’d pulled my goggles early and had to get up front to see!”

the uphill was to always get set up for it two turns before I got to it. [This would push me to] the left side of the hill, where you could usually find a smoother line. I even built my own secret berm in practice to make it work. Then I would stay on the edge of the track, sit down and shift up.”

“Like everyone else, I had a problem with the heat. I also remember the importance of having a good race psychology. When everybody would be complaining about the heat, I would just be sitting there smiling and saying it wasn’t so bad!” “When Carlsbad got rough,” “Rocket Rex” Staten told Zap, “you never rode it straight, you had to ride from bank to bank on the sides of the track. DeCoster was following me, and he thought I was totally out of control because I kept swerving from one edge of the track to the other, but that’s just how you rode the place.” “My secret was that I went in the opposite direction on the bike setup from everyone else,” 1981 winner Chuck Sun relayed. “Carlsbad was as hard as concrete, and what worked for me was to set my suspension up with my sand track settings (with more rebound damping). Everyone else ran with soft settings, and that just made their bikes all wobbly.”

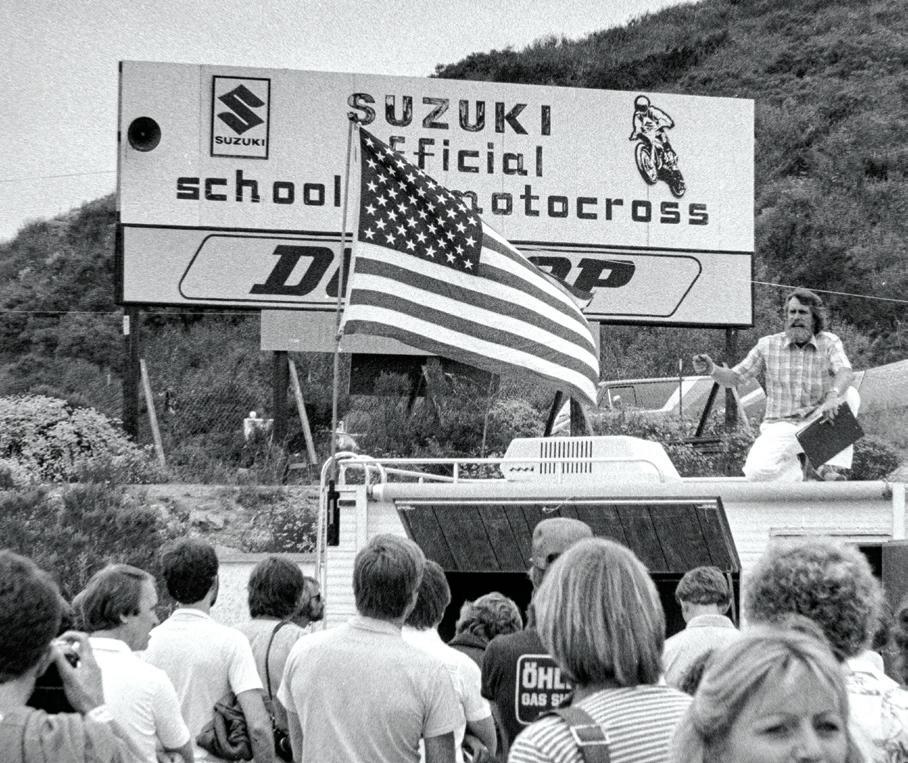

AMA 500cc National Motocross Champion and AMA Hall of Famer Mark Blackwell, who ran the Suzuki School of Motocross at Carlsbad from the mid 1970s to the early 1980s before becoming Suzuki’s Motocross Team Manager, has some pretty vivid memories of the place.

“Carlsbad was powerful stuff for me and all the students,” Blackwell told me recently, “and you could feel the anticipation and excitement building as we headed to the track on the first day of each new class. The students were clearly emotional about being able to ride there, and instead of rushing to the prepped RMs ready for them to ride, they would all walk toward the track and gawk, looking over the fence in awe. The awe only increased during our walk around the course, and students were consistently shocked at how much steeper the up-anddown Carlsbad Freeway was in person relative to how it looked on television.”

“Because the surface was so hard,” he added, “the track never absorbed water well. It was incredibly slippery when freshly watered, reasonably tacky as the surface dried, and then dusty and slick like ice within a short period. Riding Carlsbad well required incredible feel and throttle control, balance and agility, and adaptability as a rider, too, which made it exhilarating to ride but incredibly hard to pass on.”

“I always think about Carlsbad as being a terrible

place to race,” said 1985 USGP winner and AMA Hall of Famer David Bailey in that MXA interview. “They’d pour the Pacific Ocean on the track in the morning, and in the afternoon the track would be rock-hard. The bumps were still there from when Wolsink won the first time, the bleachers were sagging, and there were weeds everywhere. The place was a dump. But once you were racing at the USGP, all that went away. They hung the banners, the crowd poured in and the whole experience was transformed. In fact, I look back on racing the USGP with as much affection as I do the Gaildorf Motocross des Nations. To race the USGP was a privilege.”

Bailey’s take is absolutely perfect, and as you look back at the history of the place, the privilege, I think, was ours, too — the hundreds of thousands of fans and industry folks who poured in every year, Woodstock-like, to see the stars of our sport compete; the weekend-warrior racers who ran there when there were no spectators at all; and all the drag racers and SCCA competitors who wore out a bazillion tires in that very special plot of land just a few miles from the Pacific Ocean.

Sacred ground, indeed.

Carlsbad and Gavin Trippe’s USGP did more than elevate motocross to the big stage in America — and the world. They showed the U.S. motorcycle market what was possible. They pushed motorcycle technology, built superstars out of local heroes and, most of all, told that massive ABC television audience — and the world —

every summer for more than a decade that American riders were a force, and could put on one hell of a motocross party.

All of which makes the effort to place a permanent memorial overlooking the site a wonderful one (see accompanying story). “It makes sense,” Trippe told me years ago, when the memorial project was just getting started. “It’s a flood basin, so it’s gonna stay as-is. I think the motocross community would support it. Maybe just a wooden walkway for folks to stroll on, with a memorial plaque of some kind nearby. It would be neat.”

Not much doubt about that.

Carlsbad also featured a roadrace course, which used the venue’s famous drag strip and curvy return road. Gary Nixon (9) demonstrates. Broc Glover (right) won the ’84 USGP. “We love this place,” he said recently, “but if you tried to override [the track] it would bite you.”

A MONUMENTAL EFFORT

It’s taken more than a decade, but a historical monument to Carlsbad Raceway is nearly a reality

BY TODD HUFFMAN

In June of 2010 our movie The Carlsbad USGP:1980 — which highlighted Marty Moates’ legendary (and first-American) win at the 1980 USGP — premiered at the Spreckels Theatre in San Diego. (First time in the theatre’s 100-year history it had completely sold out, too!) Between June and October when the DVD debuted, David Moates (Marty’s brother), Scott Cox and I were talking about how cool it would be to have a monument for the raceway.

It’d celebrate everything that went on at Carlsbad Raceway, from its founding and drag racing to motocross, USGP and Superbikers events, and everything in between, including the skateboard park, the first in the nation.

We contacted the city of Carlsbad and were told by Parks and Rec that the city didn’t own — but had an easement on — a park at the corner of Melrose and Palomar Airport Road overlooking the site. They said we could use the very north end of it, which was just vegetation, and after a couple of years of scheming and a little fundraising we hired Schmidt Design in San Diego as the designers of the monument.

In the meantime we secured Road 2 Recovery as the 501(c)3 non-profit to own the project so people could donate and get a tax deduction. Jimmy Button and his mom Anita led the charge with their board, and that was a go, which we are eternally grateful for! When the design was finalized around 2016 we were ready to really announce it and start raising money, which is when the City told us we actually had to get permission from the land owner across the street, who emphatically said, “Hell, no!” Bummer... Not to be discouraged we found another site off Lionshead Ave., which was the tail end of a little landscaping owned by the Lionshead Business Park Property Owners Association. The original motocross track actually went over that exact spot. We had Schmidt Design tweak the original drawing (more $$) and went back and forth with them for almost three years until their board finally voted “no” in the Spring of 2020. They said we could put a plaque in the ground on a post. More bummer…

At that point we were running out of options, as there were just not any suitable locations on the south side of the canyon. But while talking to David Moates one day

THE DECK WILL FEATURE NINE TO TWELVE 24X36INCH INFORMATION PLAQUES HIGHLIGHTING SPECIFIC ASPECTS OF RACEWAY HISTORY — BEGINNINGS, DRAG RACING, SPORTS CAR RACING, SKATEBOARD PARK, MOTOCROSS TRACK, THE CARLSBAD USGP, SUPERBIKERS AND MORE.

we figured we’d try the north side, which lies in the city of Vista. David did some driving and found what is now the final location, which is on property owned by the fine folks at Baidee Development, and on which is located Eppig and Dogleg breweries. (How cool is that?!) We had one meeting with owner Ben Baidee, who said, “I like it, let’s do it!” on the spot. Go Ben!

Then it was back to Schmidt Design for another round of designs, which now features a dramatic-overlook deck jutting out over the canyon above the raceway site. By June 22 (the day Marty Moates won the USGP in 1980) of 2021 we had an unveiling on the site, with racers such as Don “The Snake” Purdhomme and Broc Glover in attendance.

So what exactly is the Carlsbad Raceway Monument Project? It’s a 1300 square-foot interpretive, historical monument about the history of the Carlsbad Raceway featuring a dramatic overlook of the Carlsbad Raceway site supported by caissons supporting a curved deck jutting out over the canyon.

The deck will feature nine to twelve 24x36-inch information plaques (as illustrated in the above artist’s rendering) highlighting specific aspects of raceway history — beginnings, drag racing, sports car racing, skateboard park, motocross track, the Carlsbad USGP, Superbikers and more. There will even be a special plaque for San Diego local and motocross legend Marty Smith. Plaques will also have a QR code people can scan with their phones to get a short documentary video on that particular plaque.

Over 1,200 engraved bricks will cover the ground and give families and companies the opportunity to be part of the monument, and there will be “Bench Racing” benches, too, with sponsorship opportunities. A to-scale, sculptured model of the motocross track will be the centerpiece, which kids can play on using model motorcycles.

The budget is more than $250,000 to complete, and everything is available for naming rights and donations. Also, a good portion of the construction budget can be accomplished with in-kind support from the construction community; concrete, landscaping, construction and engineering can all be donated and given a tax-deductible letter from the Road 2 Recovery. The goal is to raise funding throughout 2022 with the hope of starting construction by end of 2022. Let’s do this!

Bricks can be purchased at https://road2recoverybricks. com and for larger donations, please contact Todd Huffman at todd@pdmtv.com or (714) 305-4945. AMA