14 minute read

KAWASAKI

BY MITCH BOEHM PHOTOS :KEVIN WING, NORM BIGELOW

The discovery had to hurt. Or at least been depressing and frustrating both professionally and personally, especially in Japan, where a modern, Bushido-derived code of honor lives on in business and culture.

It came very likely by way of an urgent phone call from the grounds of the Tokyo Motor Show to Kawasaki engineer and development team leader Sam Tanegashima late in the morning of October 26, 1968 — and the news was not good.

Kawasaki competitor Honda, Tanegashima was told, had just dropped a bombshell on the Show floor — on all of motorcycling, really — with the debut of its advanced, mass-production-spec

CB750. The big 750 Four would usher in an entirely new era in the motorcycle world during the coming years, but it was the new Honda’s devastating short-term effect on Tanegashima’s development team and on Kawasaki itself that was most concerning.

The reason was easy enough to understand, because at that very moment Kawasaki was about to green light full-scale development of production tooling for its own inlinefour 750-class motorcycle, code named N600, which was to debut a year later at the 1969 Tokyo Motor Show as a 1970-spec model.

Kawasaki’s N600 was to be after this new Honda would surely be seen as copycatting even if the bike was functionally as good. And if it wasn’t? Well, that’d be a seppukustyle death sentence for the bike sales-wise, and certainly a loss of face for the company.

And just like that, the N600 project imploded.

From 750 To 903

We can only guess about the R&D meetings and internal discussions that occurred in the wake of the CB750’s launch regarding the next chapter of Kawasaki’s big-bore fourstroke plan — which would end with the glorious debut of the legendary groundbreaking, a street machine powered by a twin-cam (not singlecam, as with the CB750) four-stroke four wrapped in contemporary bodywork, and a bike that would help the company break free from the two-stroke cocoon it’d worked from previously. Kawasaki’s fast-butrough-edged two-stroke H1 of 1969, which debuted alongside the CB750 in Tokyo, was in ways impressive, but up against what looked like nothing less than the all-new four-stroke flagship streetbike from Honda; there was really no comparison. And Tanegashima knew it.

Few images in motorcycling’s vast history conjure as many mental goosebumps as a first-year Z1 in its root beer ’n orange livery. Left: Kawasaki’s 750cc N600 prototype, just before it was binned due to Honda’s shocking release of its CB750 in late 1968 — and Kawasaki’s desire to build a “King of motorcycles” in the new Honda’s wake.

The news was devastating to Kawasaki, which understood all too well that releasing its own 750 a year

903cc Z1 in late 1972 on that same Tokyo Show floor. There had to be consternation, and certainly some hard questions were asked. But it’s simplistic to blame the new-generation Z1 completely on Honda’s big move.

As we know from the N600 project, and from Kawasaki’s purchase of competitor Meguro in the early 1960s (and sales of its Meguro-derived W1 and W2 models of the middle and later 1960s), Kawasaki was already moving toward four strokes, and bigger ones. It wasn’t hard to see that its vibey, loud and smokey two-strokes, as fast and interesting as they were, were not the future, especially in the increasingly luxury- and emissions-conscious U.S. It was a point Honda was making quite effectively by the latter 1960s with its quiet and friendly four-strokes, not to mention its “nicest people” campaign.

KAWASAKI WAS ALREADY MOVING TOWARD FOUR STROKES, AND BIGGER ONES. IT WASN’T HARD TO SEE THAT ITS VIBEY, LOUD AND SMOKEY TWO-STROKES, AS FAST AND INTERESTING AS THEY WERE, WERE NOT THE FUTURE.

Still, the CB750’s launch very definitely rallied the troops in the Kawasaki camp, and gave team members a renewed sense of purpose as they talked and planned and set into motion a whole new round of concepts, sketches, clay models and running prototypes, motorcycles, like the A7, H1 and H2. [The company] was not sure if [it was] selling engine/horsepower, or motorcycle. From the very beginning of Z1 development, we made sure to develop one piece of motorcycle, not independent engine or chassis.”

Tanegashima also mentioned the Japanese penchant for a “me too” approach. “Our people tend to like to do the same thing as [their] neighbor. In product development, this tendency leads to [copying] some from the U.S. asked for a 4-cylinder 4-stroke machine, [R&D Manager] Mr. Hamawaki had pushed for a talented engineer from Kawasaki’s aircraft division to be brought in – a Mr. Otsuki, I believe. After all three engines blew up, “HP” (Otsuki’s nickname) began asking for a larger, better engine; hence the 903.”

Z1 Development

all of which would culminate in the release of something bigger, faster and even more sophisticated than the new Honda — a true “King of Motorcycles,” as one manager put it. It would take the better part of four long years to get it done, but Tanegashima’s guys were determined to get it right.

Aside from simply moving from two-strokes to four, Kawasaki was also in the midst of changing its approach to building motorcycles. As Tanegashima said in Micky Hesse’s excellent book Z1 Kawasaki, “One motto we had for developing the Z1 was to create one piece of motorcycle. Before the Z1, Kawasaki had developed several very fast competitors or leaders. However, [our] motto in developing the Z1 was to make it completely different from Honda’s CB750. This [is] a very rare case in Japanese society.”

Other considerations made pulling the plug on the 750 project easier, as well. During development in ’67, the three slightly different prototype engines the engineers built were proving seriously fragile.

“The testing done in Japan at the [now defunct] Yatabe circuit with [U.S. racers] Walt Fulton and Art Bauman,” Kawasaki man — and the late — Don Graves told this author a decade ago, “proved that the engines they’d built were not dependable. When the original push

The question “Why build such a machine?” sounds almost humorously rhetorical with 50 years of hindsight, but in Cycle magazine’s road test in its November 1972 issue, Kawasaki General Manager T. Yamada answered it this way: “Lots of reasons.” Kawasaki, he said, wanted to build the “King Motorcycle,” a bike beside which, Cycle surmised, the finest motorcycles in the world would shrivel in comparison…a bike that would leave a hot and smoking scar across the face of the sport…and you just can’t do it, Yamada was saying, with a two-stroke engine. In the first place, he said, the King Motorcycle must have an engine that sounds right.

“No less important,” Yamada added, “is the way the engine looks. Who could imagine a King Motorcycle with an engine that looked like a twostroke engine looks, all crankcases and cooling fins? The King…has to have an engine that looks impressive. And only a big four-stroke is right.”

Still, a bit like the stillborn 750, the 903cc Z1 project had plenty of headaches along the way, and early in development was nothing at all like the refined and well-sorted production bike that debuted in late ’72 to such overwhelming accolades.

“It was actually pretty awful at first,” remembered Kawasaki man Bryon

Running prototypes are rarely beautiful, and this Z1 test mule is no exception. But the shapes and basics are all there, and one wonders…did engineers and brass know the shocking impact their new open-classer would have on the world?

Farnsworth, who was recruited from Cycle in ’71 to become the senior U.S. test rider for Z1 development. “I was the first American,” he said, “and the only American to go over to Japan to test it. We’d scheduled time at the high-speed, bankedoval Yatabe test course, but it was booked when we arrived, so we did some testing in a big parking lot, with cones. That sucked, but at least we got to ride. The thing dragged its mufflers right away, and I could tell, even at those slower speeds, that the engine, chassis and suspension were in need of serious help. At that point I think they were still in an H1 frame of mind, where the chassis didn’t matter

AMA Motorcycle Hall of Famer

Gary Nixon, Paul Smart and Hurley Wilvert, all of whom flogged the bikes mercilessly at the racetrack and on the road. During one trip from Los Angeles to Daytona and back, the bikes had big Honda stickers on the tanks to keep public curiosity to a minimum. (The subterfuge didn’t always work, with some humorous results, according to Farnsworth.)

Early on, Kawasaki was deeply concerned about the bike’s durability and reliability, and rightfully so. Problems there could not only scuttle the Z1 in the marketplace, but sink Kawasaki’s reputation, as well. Of course Farnsworth knew just where much and it was all about straight-line speed. And with the Z1, you had this great big powerful and heavy engine sitting there, twisting everything into a knot. I told them it was a “rakuta,” which is “water buffalo” in Japanese!”

Farnsworth made several trips to Japan in those early days, one lasting nearly two months, and little by little the prototypes got better. “After the Yatabe experience,” he said, “I insisted we go to a real track, and we were able to get some time at the Tsukuba circuit. We made some progress there, and it helped once the updated prototypes got to the U.S. later in the development cycle.”

The team tested over several months in the U.S., from Southern California to Florida and several spots in between. Farnsworth gathered a host of riders to help out, including to go — Talladega Superspeedway. So in late 1972 the entire Kawasaki Z1–testing entourage descended on Talladega, which they’d rented for 30 days.

There the bikes were run at full throttle until they ran out of fuel — and then refilled and run again until empty. “Riders were going almost 140 mph,” Farnsworth remembered with a laugh. “The bikes would wiggle at speed, but only if you let off. If you had the balls and held it wide open, it was OK.”

Despite a few niggles, and that topspeed shimmy, the Z1 had become a pretty solid motorcycle during those many months of prototype testing. “I think my input early on, when the Z1 was really rough, was a key factor in the model’s success,” said Farnsworth. “We really did try to make the bike bulletproof for American riders. I’m really proud of that.”

After all that testing on dynos, roads and racetracks, the only even slightly unseemly trait the Z1 demonstrated was an apparent appetite for rear tires and finaldrive chains, consuming the former in about 6,000 miles, the latter in roughly half that distance.

As pre-production bikes (those hand-built with mostly production parts) began to become available in mid 1972 for final performance and emissions testing before actual assembly-line production could begin, the Z1 team felt reasonably comfortable with their efforts. Farnsworth felt similarly and came up with an idea that would help launch the bike to the press and public in dramatic fashion.

“I suggested we go to Daytona and set all the world FIM and AMA 24-hour endurance records,” Farnsworth told this author.

“Thankfully, upper management agreed, and we put together a plan. We knew from all the highspeed testing at Talladega that the production Z1 would easily smash all the records at the time, as it would run 140 mph all day long. The record at the time for a 24-hour average was held by a Suzuki at just 90.1 mph, so we knew we could make some noise with this.”

Farnsworth’s record-assault team, including Hall of Famers

Gary Nixon, Yvon DuHamel, Cycle magazine Editor Cook Neilson and others, arrived at the Speedway to see what the new Z1 could do. Turned out it could do a lot, slaughtering the Suzuki’s record by almost 20 mph with a 24-hour average of 109.64 mph for 2,631 miles. A special one-off Z1 tuned by Yoshimura and ridden by Duhamel set a new single-lap speed record of 160.288 mph.

“It was a bit of a gamble,” Farnsworth remembered, “because a lot of things could have gone wrong. But it paid off, especially by using credible members of the media — who’d all write about it — and also current AMA racers to set the records. Folks could see the bike was crazy fast, but bulletproof, too. It was wild going into the Daytona banking at 140 mph; it looked like a wall as you approached it, and holding the throttle open and not backing off took some doing!”

Z1 Makeup

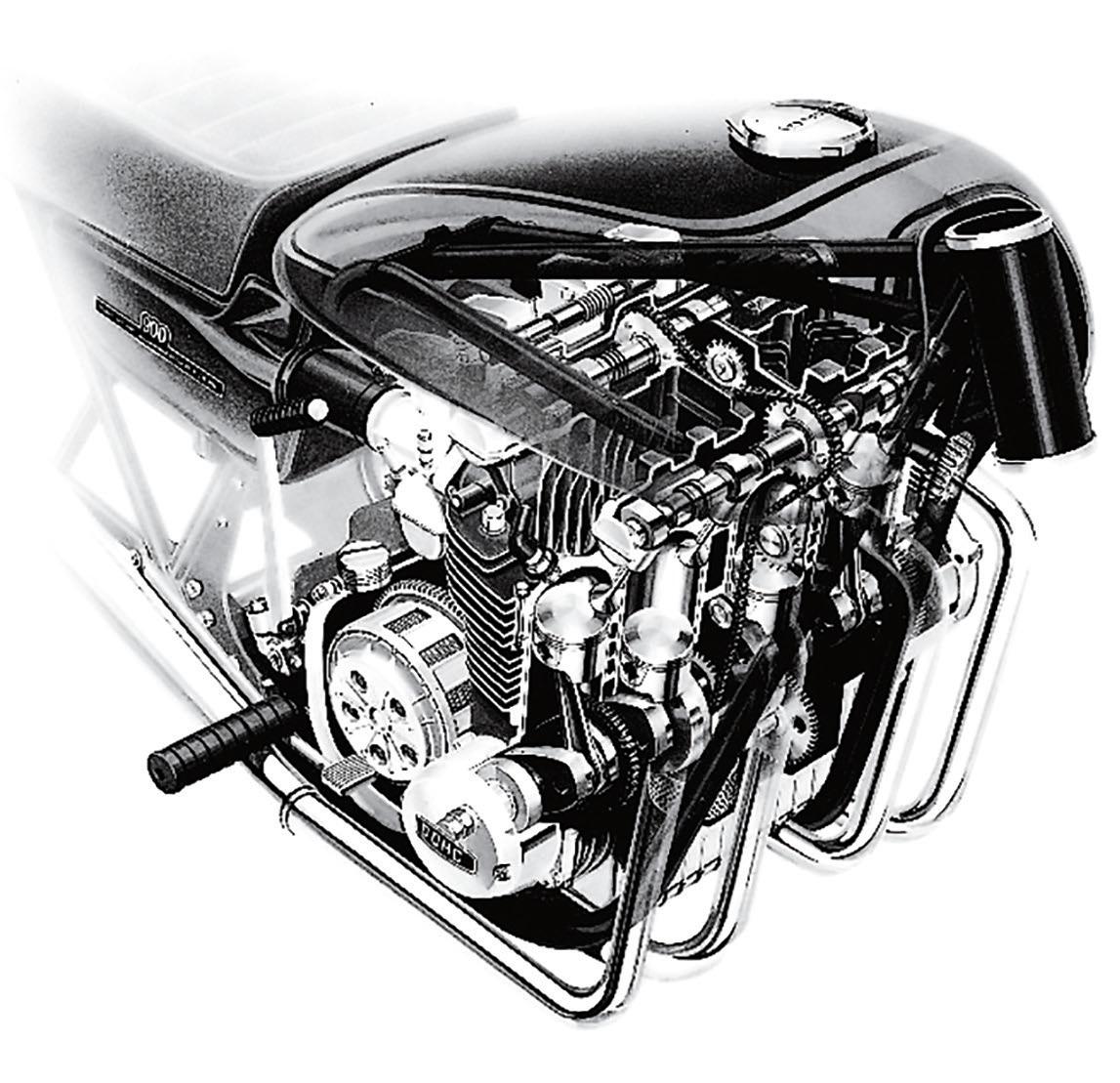

So, what was so special about this King of Motorcycles? From day one the Z1 was all about that engine — a beautifully sculpted, air-cooled inline-four with dual camshafts that displaced 903cc from square bore and stroke dimensions of 66mm x 66mm and produced (according to Kawasaki) 82 crankshaft horsepower, 15 or so more than Honda’s longerstroke, single-cam powerplant. As Cycle’s road test put it, “Horsepower flows…like water from an Artesian well. It simply never stops.” It did stop, of course, but by the time it did most street riders would be plenty happy about it.

Below all that DOHC induction magic and smooth, midrange-focused power spun a nine-piece, pressedup roller-bearing crank with caged needle-rollers for each con rod to ride on, an overbuilt 5-speed transmission and a beefy wet, multi-plate clutch. This obvious strength belowdecks caused Cycle magazine to write, “The lower end looks like it came out of a Porsche Carrera,” and was backed up with proven performance and durability on the streets, racetracks and dragstrips of the world for many years to come.

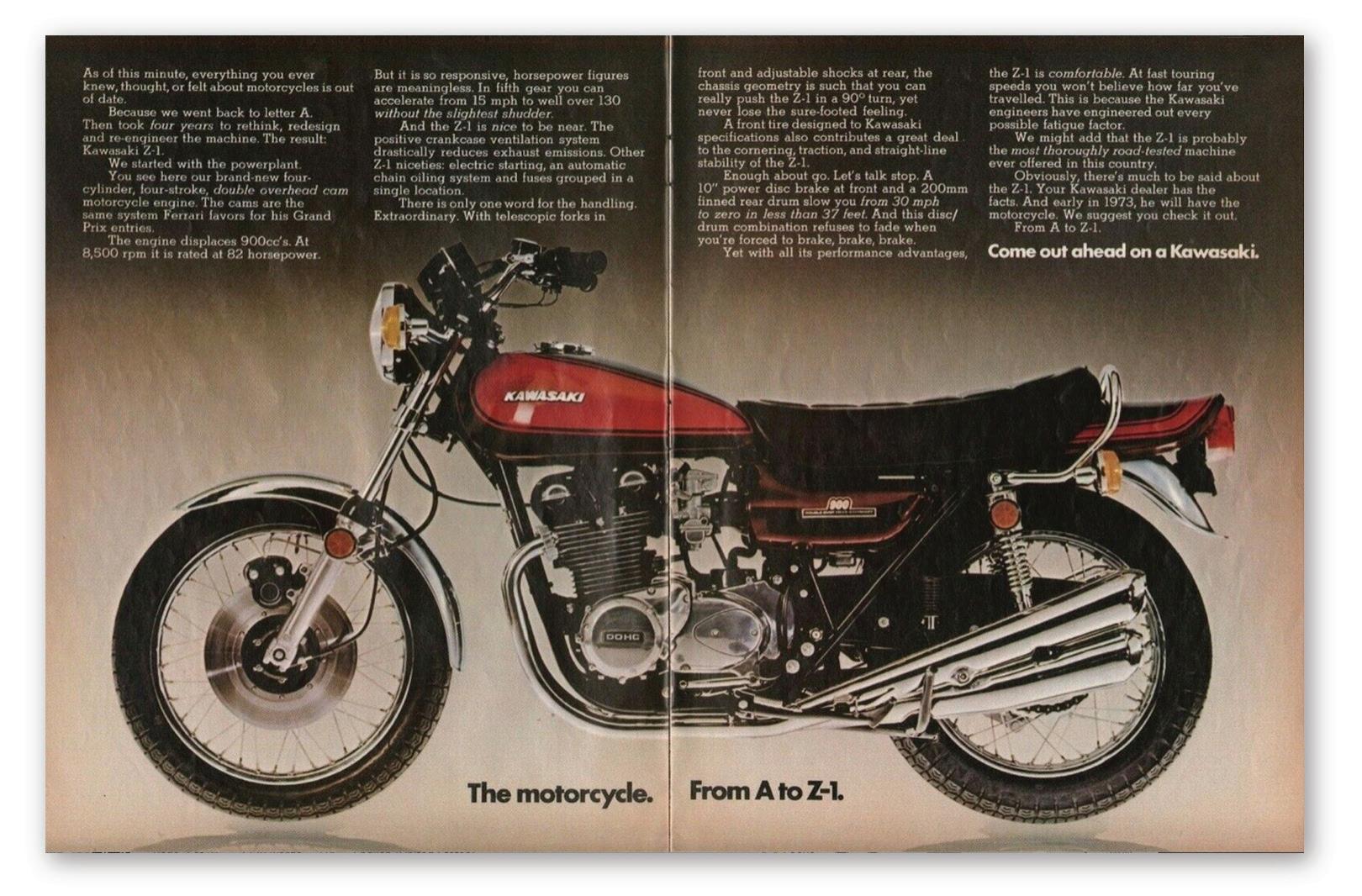

Compared with the engine, the rest of the motorcycle — dual-downtube steel frame, spoker wheels, a singledisc/drum brake setup, el cheapo shocks and skinny-flex fork tubes — was pretty conventional, though Kawasaki stylists did manage a bangup job with the bike’s aesthetics. From the teardrop fuel tank to the sporty, flip-up tail section to the fat-’n’-flared mufflers and everything in between (including that lovely, slim-waisted and wide-shouldered engine), the Z1 looked considerably curvier and sexier than the then-fiveyear-old Honda.

It’s often noted that Honda made it easier for the Z1 to shine from 1973 onward by not upgrading its world-changing CB750 until the late ’70s, and by the numbers that’s true enough. Some still say Honda was being lazy on the big streetbike front during those years, and maybe it was. But Honda was seriously busy in the early and middle 1970s, filling out its vast motorcycle lineup with a wide array of sensible machines to become the envy of every maker on earth. Remember Honda’s 1973 sales slogan From Mighty to Mini, Honda Has It All? You probably do, and it did. Oh, and the company was also developing its Civic automobile — and Clean Air Act-meeting CVCC technology — for U.S. and worldwide consumption, all of which resulted in the auto giant becoming an auto giant during the 1980s.

Launch Time

When released to dealers in early

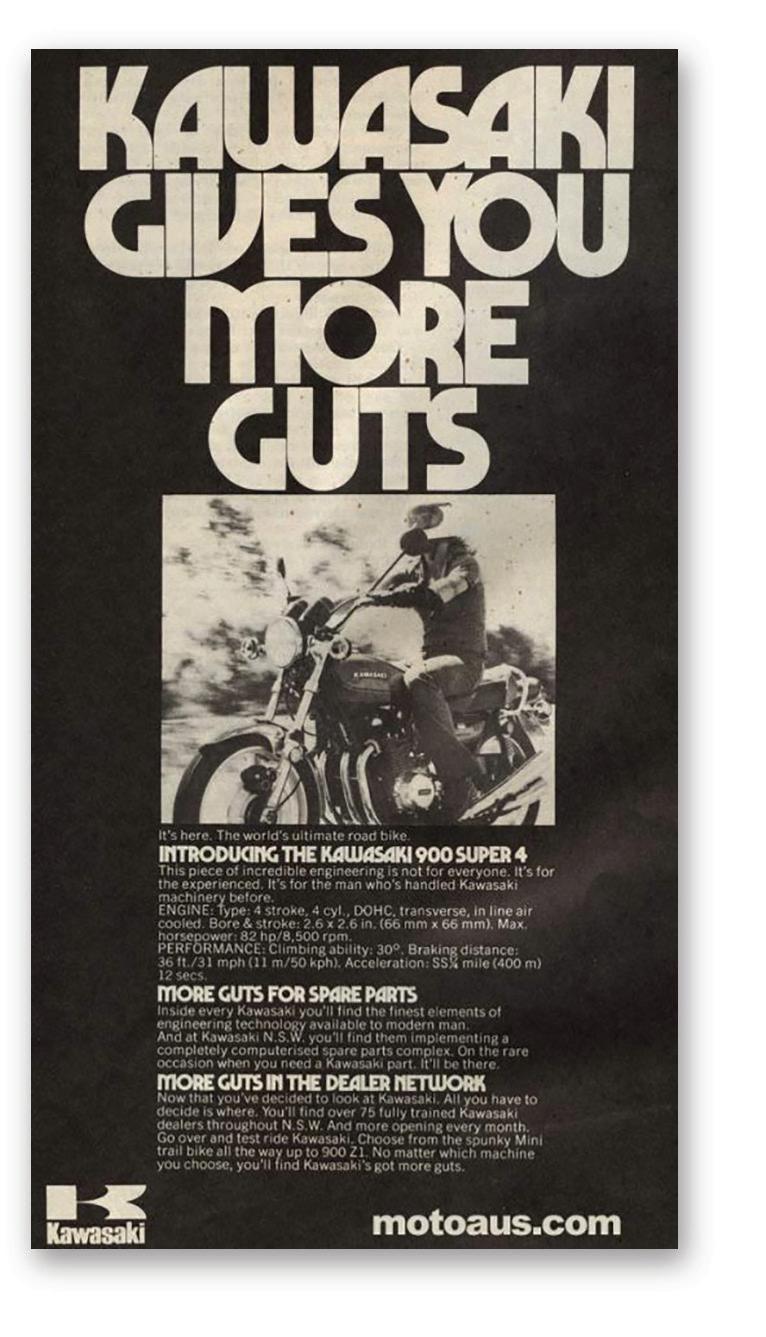

’73, Z1s began immediately flying out of Kawasaki showrooms, with heavy advertising and hugely positive magazine reports helping keep the momentum — and dollars — flowing. Kawasaki reportedly wholesaled more than 80,000 examples in the first two years alone. Before Z1s first became available, Honda’s CB750 and Kawasaki’s own 500cc H1 had stolen much of the Big Streetbike thunder in America from HarleyDavidson and the British/Euro makers. And while the appearance of the 750cc H2 in late ’71 added to the two-stroke momentum Kawasaki had generated, the launch and appearance of the comfortable, refined, smooth, quiet and downright ass-kicking Z1 changed the conversation overnight.

Spindly frames and pencil-thin fork tubes were easily overwhelmed by the Z1’s heavy and powerful engine (especially with Pops Yoshimura working his horsepower magic) in early AMA Superbike racing. Z1 riders such as Yvon DuHamel had to run treaded tires instead of slicks, with toogrippy slicks making the bike almost unrideable.

Here was an under $2,000 motorcycle that seemingly did it all, from around-town runner to comfy tourer to dragstrip demon to backroad burner and, by the middle 1970s, a plenty-competent Open Productionclass road racer — which led to it becoming the one of the foundational machines in the launch of sanctioned AMA Superbike racing in 1976. They don’t call the Z1 the first Superbike for nuthin’.

Al Arbor, who ran Kawasaki East in Nashua, New Hampshire for nearly two decades, said the Z1 was key to building Kawasaki’s reputation in the U.S. “The Z1 really did do everything,” he told this author, “and a lot of guys used that to their advantage, telling their wives the bike would be for them to travel on. Once they got permission to buy it, it was often a different story! It was fast and comfortable and nearly indestructible, and we drag raced them for years. Those were good years.”

Once loosed on the streets, dragstrips and racetracks of America (and the world), the Z1 would go on to have some very good years, with

Honda’s reluctance to upgrade its flagship model (over and above the GL1000 of ’75) doing nothing to dilute that effect. Kawasaki, on the other hand, began making improvements to the Z in ’76 with the Z900 and, later, the Z1000 — all of which led to the

J-model KZ1000 and, later, the ELR, GPz and Ninja models of the 1980s. The company that dug deepest into Kawasaki’s big streetbike market share was Suzuki, with its brilliant GS750 and GS1000 of ’76 and ’78… but that’s another story entirely.

Despite the Z1’s 80-plus horsepower and fairly sporty handling, it was also a competent tourer, with plenty of midrange and enough smoothness and comfort (despite the waffle grips!) to keep rider and passenger happy. Right: Z1 variants through the years, from the Z900 to the Z1-R, which set the stage for the ELR, GPzs and 900 Ninja that’d come later.

Fun Facts

According to Kawasaki’s website, the Z1 name came from Z being the last letter of the alphabet, which represented the most extreme position, with the number 1 representing “number one” in the world. Another bit of irony regarding the Honda/ Kawasaki connection here is the Honda CBR900RR of 1993, which debuted 20 years after the Z1’s introduction. Like the Z1, the 900RR was, during development, a 750, and got all the way to late-prototype stage before Honda changed course, feeling a 900 would have more market impact — which it did. Like Kawasaki’s decision to move up the displacement ladder and build the Z1, Honda’s move was a smart one.

Z Bottom Line

In short, Kawasaki’s 900 Super Four Z1, as it finally came to be known, was nothing less than a revelation — a motorcycle that shined a bright orange spotlight on the future of motorcycling, a direction every other manufacturer ignored at its peril. That direction was performance-oriented, for sure, but it wasn’t a narrow-focus or harsh sort of performance as represented by, say, Kawasaki’s Mach III or H2. It was balanced performance — speed and power, for sure, but also comfort, quietness, smoothness, civility and durability…as inviting and inclusive as the two-strokes could feel hostile and divisive.

The Z1 didn’t quite generate the all-inclusive big-tent appeal of Honda’s CB750; there was still a bit of an edge to the bike, a subtle feeling of Us vs. Them, which, given the bike’s semi-tortured birth, was maybe not an accident.

But 50 years later, most of us know what motorcycle is being referred to when we read this famous road-test quote: “Every inch a King…” AMA

BY JOY BURGESS PHOTOS BY SHAN MOORE

If you’re into motorcycle racing at all, you’re probably familiar with the Haydens and Bostroms in AMA and World Superbike, the Stewarts and Lawrences in AMA Supercross, and the Baumans in flat track — all brothers who’ve raced at the highest levels in their disciplines.

But you might not have heard of Steward and Grant Baylor, brothers who’ve dominated AMA National Enduro for the past decade

Between the two, they’ve won seven of the past 10 AMA National Enduro championships, with Steward winning in 2012, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2021, and Grant in 2020 and 2022.

“Racing’s kinda in our blood,” Steward told American Motorcyclist with just a touch of sarcasm. “I’m