11 minute read

COVER STORY: TALKIN’ SHOP

TALKIN’ SHOP

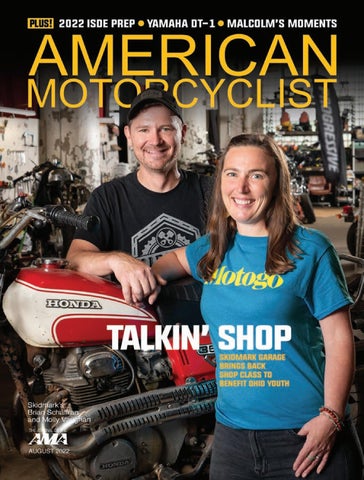

Brian Schaffran and Molly Vaughan’s Skidmark Garage Motogo program is bringing back shop class — with a two-wheeled twist — to benefit Cleveland’s youth

BY KEATON MAISANO PHOTOS BY GARY YASAKI

Once a staple of the American education system that introduced skills such as wood-, leather- and metal-working, welding, mechanics, electronics and much more to middle and high school students, the shop class concept is gone, and the results are not pretty. Among them, a severe labor shortage in the skilled trades and, either directly or indirectly, a $1.6 billion student-loan crisis, with students since the 1970s pushed toward four-year degrees as the only path to prosperity.

TV personality and author Mike Rowe is one of many who’ve criticized this societal shift in interviews and columns. “We have unintendedly maligned an entire section of our workforce by promoting one form of education at the expense of all others,” he said recently. “Our leaders told students if they didn’t get a degree they would wind up ‘turning wrenches,’ and that attitude led to the removal of shop classes and eliminated the proof of opportunity for generations of young people.”

Of course, like vinyl records, turntables, Polaroid cameras and print magazines, fun and/or useful things pushed aside by technology or “new thinking” have a way of sneaking back into the mix, which is something Brian Schaffran and Molly Vaughan of Cleveland’s Skidmark Garage know a little something about.

The husband-and-wife duo are five years into a program they call Motogo, a nonprofit 501(c)(3) that serves as the educational wing of their Skidmark Garage — a community garage where members pay a fee to have access to tools, equipment and a workshop bay — that is designed to teach both middle school and high school sturemix of an old classic. “We are essentially bringing shop class back,” he said. “It used to exist in all the schools until recently, except instead of working on lawnmowers and birdhouses, we are doing motorcycles, so that’s the hook.”

Vaughan, who serves as the Executive Director of Motogo, agrees, and said there’s beauty in watching kids work on themselves while they work on a motorcycle.

“One nice thing about [the CB350] is how accessible the engine is,” she said, “and how visible. We are trying to get the kids to be authentic, and a motorcycle like this isn’t hiding who it is. What you see is what you

BRIAN SCHAFFRAN

dents how to solve problems through working on motorcycles.

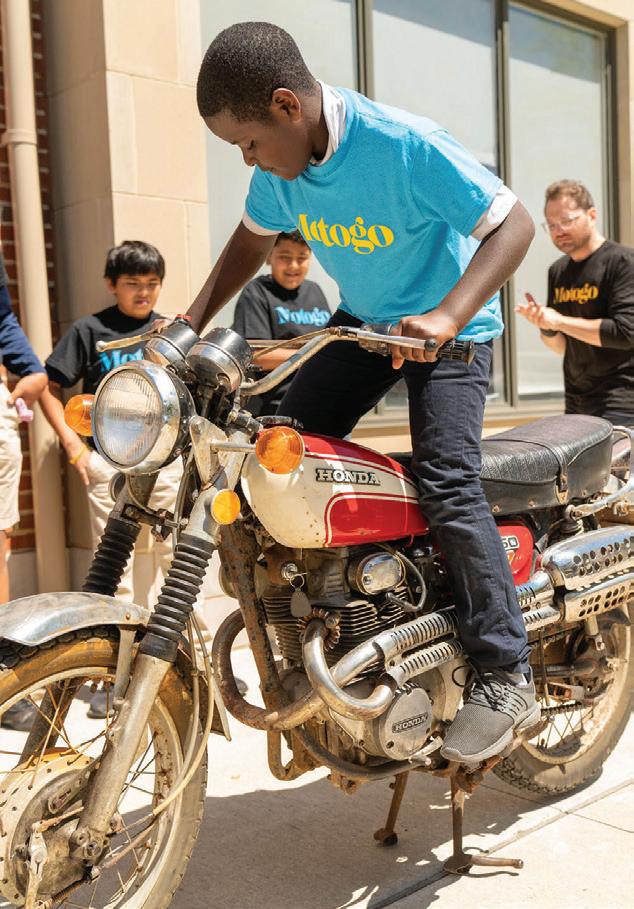

Working with more than a dozen schools in the Cleveland area and built on the pillars of working with your hands, self-confidence, authenticity, equity and community, Motogo offers schoolkids the chance to rebuild 1970s Honda CB350 engines in one program and the entire motorcycle in another with the objective of sparking a newfound confidence in each student.

Schaffran said it’s really just a get. There are no secret parts hiding under chunks of plastic, so it’s kind of a metaphor for the kids, like you’re working on your insides that are visible to the outside.”

Schaffran, who was Motogo’s first coach, notices firsthand how daunting the freedom to have access to an entire engine or motorcycle can be to students. “They’re like that stereotypical deer in the headlights,” Schaffran said. “They’re afraid of breaking something, or of being embarrassed because they’re guessing wrong, or

they’re holding the tool wrong.”

Even a simple task like removing the seat leads to indecisiveness. Schaffran said he lets the students “suffer for a couple of minutes” before he steps in to help. “And that’s the first victory,” he said, “figuring that out. When they get that seat off, it’s like they won the lottery.”

Schaffran said even the small bit of confidence and momentum built from getting the seat off enables them to complete the next task more efficiently. And while the process can be upsetting, Schaffran and Vaughan have designed it to build confidence, not destroy it.

“Our mission is really to redefine failure,” Vaughan said. “People often think failure is a steppingstone to success, but we’re trying to teach that sometimes failure is the success.”

Elise Kavalchek is one student given the freedom to fail within the Motogo program and benefited from it. The 17-year-old senior has been through the Motogo program twice — once with the CB350 engine rebuild and again with the whole-bike rebuild.

Kavalchek even purchased her own CB350 to work on at Skidmark Garage. She elected to take the engine rebuild program as part of her school’s Immersion Week because it aligned with her interest in becoming a mechanical engineer.

“It wasn’t just about learning how to work on engines,” she said. “It was also problem-solving, because they’re not new engines and there will be problems with them. I learned a whole lot about problem solving through this experience.”

Each Motogo program ends with Kickstart Day, an opportunity for the students to kickstart a motorcycle and see the culmination of what they have been working on throughout the class. “You can see how your work goes into the entire motorcycle,” Kavalchek said. “And it’s pretty cool to see a whole motorcycle when we were just working but also gave me the idea for the community garage.”

He began a decade-long career as a high school history and math teacher working at the Cleveland School of the Arts and St. Martin de Porres High School, where he met Vaughan. And it was at St. Martin during a week-long nontraditional teaching program in 2010 that Schaffran taught his first group of kids how to work on a motorcycle.

Schaffran and 12 students set out to rebuild three Honda CB750s, and while the effort ended badly with parts scattered everywhere and none of the bikes running, he learned a lesson that he’d be teaching to students less than a decade later as part of the Motogo program: sometimes failure is the success.

“It didn’t matter that we didn’t get them running,” Schaffran said. “They just were pumped as hell that they got their hands dirty and took apart those motorcycles, and I slowly realized it wasn’t a failure. I just had the wrong expectations.”

Inspired by seeing his students enjoy working on motorcycles, and from the community garage idea that was born in his mind in the 1990s, Schaffran left teaching in 2013 to pursue his dream — a dream that culminated in Skidmark Garage in 2015.

The garage operates under a membership format where members can pay a fee — annually, monthly or by the hour — to have access to tools, equipment and a workshop bay. Members also have access to the garage’s lounge area, which hosts various events such as graduation parties and weddings.

The community, do-it-yourself format is not unique for garages, but it is rare. Schaffran said he created a network of around 40 similar garages throughout the world to share ideas. “Everyone operated slightly differently,” Schaffran said, “which was great. We all learned from each other.”

While that number dwindled to around 10 due to the impacts of COVID-19, Skidmark Garage re-

on a small part of it.”

Nowadays, Schaffran sees plenty of kids like Elise kickstart their first motorcycle, but there was a time when he wasn’t familiar with motorcycles in the least. He first rode a motorcycle — a Honda Rebel — in the 1990s while living in Los Angeles. But he didn’t buy one for himself until 2002 — a 1978 Honda CB750 he saw on the side of the road while attending Cleveland State University. “I just pulled over, missed my class and bought it right there on the spot,” Schaffran said.

Schaffran’s time in LA also contributed to his idea of opening a community garage when a garage owner, Jose Gomora (of Gomora Automotive), graciously provided tools and instruction so he could repair his Volkswagen bus. “Gomora putting his trust in me not only pushed me to go back to school and finish my degree,

mained strong. Schaffran credited the generosity of both members and nonmembers who pitched in to keep the garage afloat through the pandemic.

“People just came out of the woodwork,” Schaffran said. “Even people that aren’t members, kids I was friends with in my childhood that don’t live anywhere near Ohio reached out and were like, ‘What’s your rent? I’m gonna pay it for you this month.’ And that just got us through.”

Schaffran noted that Progressive Insurance also played a role when it jumped on as a sponsor after noticing Skidmark Garage’s welcoming culture — a culture largely pioneered by Vaughan. “There’s a hashtag on both of our businesses that says, ‘All are welcome who welcome all,’” she said. “Welcoming all is tricky sometimes, but it does feel as though carburetors bring people together.”

The welcoming environment is apparent in the diverse membership base. Schaffran expressed his gratitude to Vaughan for altering his original vision of making Skidmark Garage a “man cave.” “I’m forever thankful that she pushed me in that

other direction because it’s way more fun down at Skidmark,” Schaffran said. “People that are very different from each other are coming together over a motorcycle, and whatever differences they may physically see, are all looked past.”

The emphasis on inclusion and diversity does not stop with Skidmark Garage, as Motogo is built on the same value of proper representation, especially in the program’s board and staff of coaches. With diverse representation in leadership positions, Vaughan feels the program better resonates with classes that are themselves very diverse.

“If coach Emmy [Osicka] can ride a motorcycle to class,” Vaughan says about girls learning from a female instructor, “I think that it makes you think about even more than the thing in front of you…it really opens the world of possibilities.”

To emphasize the welcoming feel Motogo aims to have, instructors are referred to as coaches. “We prefer to be called coaches so that we differentiate ourselves from teachers,” Schaffran said. “I don’t want our class to feel like a class. I don’t want them to associate it with sitting at a desk, so I try to make it feel as unlike school as possible.”

Motogo’s handful of coaches worked with more than a dozen schools — ranging from all-girl private schools to public schools in underprivileged areas — in Cleveland during the spring semester, with many more schools on a waiting list as the demand has outgrown the supply of instructors.

BRIAN SCHAFFRAN

In addition to increasing the number of coaches — which has been handled with care to maintain the high level of instruction the current group possesses — Skidmark Garage and Motogo got new digs at the end of 2021 to better host both businesses. In the new building, Skidmark Garage finds its home on a 12,000-square-foot first floor of an old warehouse, and Motogo has a dedicated 5,000-square-foot space on the third floor.

With both Skidmark Garage and Motogo on healthy trajectories, it could be easy to dream of expansion outside the Cleveland area, but Schaffran and Vaughan are committed to focusing on the here and now.

Still, when it comes to dreaming big, Schaffran acknowledged that the perfect outcome of the Motogo program is one where Motogo is no longer needed.

“It’s weird to think that we will know that Motogo is successful if we go

out of business,” Schaffran said, “because [once] every school realizes the importance of shop class, and they bring it back themselves, they won’t need us anymore. And in a way, that’s kind of the goal…to have shop class back everywhere and kids really into taking it.”

For many students of Skidmark Garage’s Motogo program, working on motorcycles is not — and may never be — a part of daily life. But that does not mean motorcycles haven’t impacted their lives. AMA