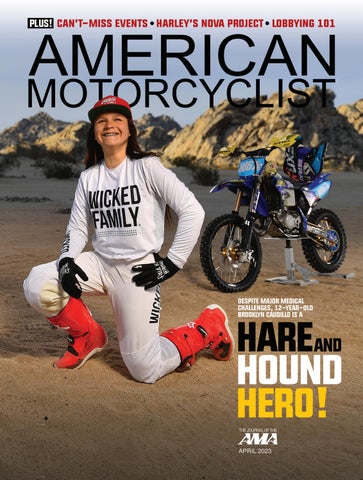

11 minute read

ROAD NOT TAKEN

much a decision for the ages:

Should this newly-purchased-but-legendary company — Harley-Davidson Motor Company, in many ways the Big Daddy and Grand Poobah of motorcycle manufacturers — continue to develop its line of V-Twin motorcycles despite their lackluster performance, functionality, durability and reputation…or build an entirely new line of modern, higher-tech machines that would (hopefully) compete directly with Japan Inc.?

Money was scarce at that point, the new ownership group having just leveraged itself silly to purchase the company from AMF (American Machine and Foundry, which had purchased H-D in 1969), so it could not do what made the most sense…which was to do both, and thereby create a hedge against the possibility of failure. So they had to choose…V-Twins or higher-tech Novas?

We know what happened, of course. But at the time, in a country struggling through a recession, with bike sales down and Harley’s fortunes at probably an alltime low, the need to do something different, something bold, and something laced with the new technology available at the time — as the Japanese makers were doing to great effect — had to be strong.

There’s little doubt that Harley-Davidson’s Nova project of the late ’70s and early ’80s is one of the most epic what if stories in all of motorcycling. The Motor Co. spent millions during the Nova line’s four-year development window, yet passed when it came time to commit to actual production, and to this day folks in the know debate the decision’s ramifications.

Whether you’re up-to-speed or not on Nova particulars, most motorcyclists of a certain demographic remember pretty clearly the time period in which this mostly unseen drama took place. The mid to late 1970s were very much an anxietyand problem-plagued time for the Motor Company. While Milwaukee struggled with leaky, low-tech and low-output V-Twins, weak engineering, questionable reliability and, at times, out-of-touch AMF leadership (which pushed Harley to build more motorcycles than it could reliably build, with disastrous results), Japan Inc. was about to launch a technological wave of Saturn V rockets in the form of liquid-cooled engines, monoshock suspension, perimeter frames, 16-inch wheels, 100-plus horsepower engines, turbo-charging and 11-second quarter mile times — and all of it blessed with cruiser and sporty styling that would have millions of boomer enthusiasts swooning in a major way.

Those 14 letters on every Harley-Davidson fuel tank still packed a lot of emotional and historical punch, as did the bikes’ bare-knuckle styling. But performance and build quality just didn’t back things up.

Few at the Motor Company were happy with the status quo. Jeff Bleustein, who signed on in the early 1970s, and AMA Hall of Famer Vaughn Beals, who came aboard in our country’s bicentennial year, understood the company’s dire situation and made plans to help it change direction, setting up a series of strategic meetings at Pinehurst golf resort in North Carolina.

There, a group of engineering, marketing and design heads developed a two-pronged pathway to help rejuvenate the company, one designed to appeal to two different but very important groups in the motorcycling universe: first, traditional Harley customers who understood the history and brand strength of the Motor Company’s products, and secondly, a more performance- and techoriented customer, many of whom had grown up with Japanese machinery, and most who would never consider owning and riding one of Milwaukee’s old-tech V-Twins. The first pathway involved an entirely new V-Twin engine (which would become the legendary Evolution engine of 1983) for traditional customers, and alongside it a range of liquid-cooled, 60-degree, high-tech V-Twins, V-Fours and V-Sixes from 500cc to 1000cc in a range of chassis flavors for the latter group. This was the Nova lineup, designed to expand Milwaukee’s customer base and build a bulwark against the coming wave of techheavy machinery that Beals, Bleustien and Co. knew in their bones was coming.

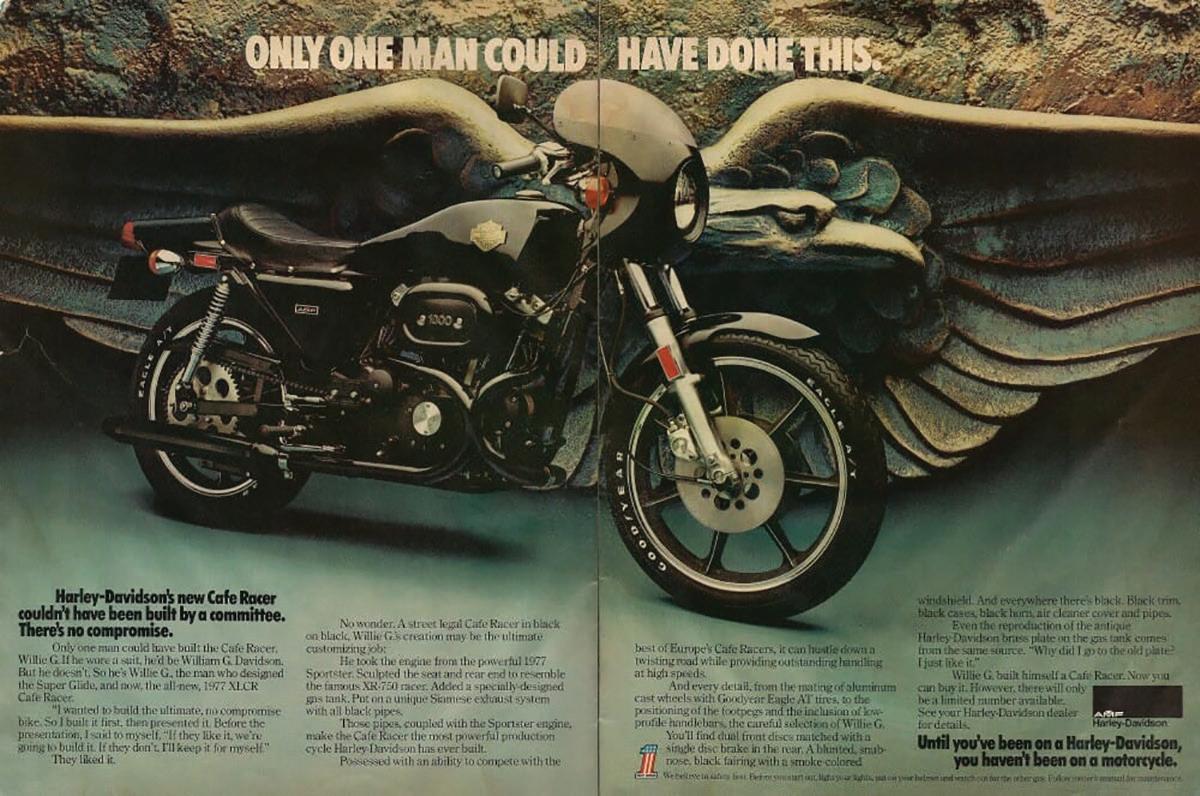

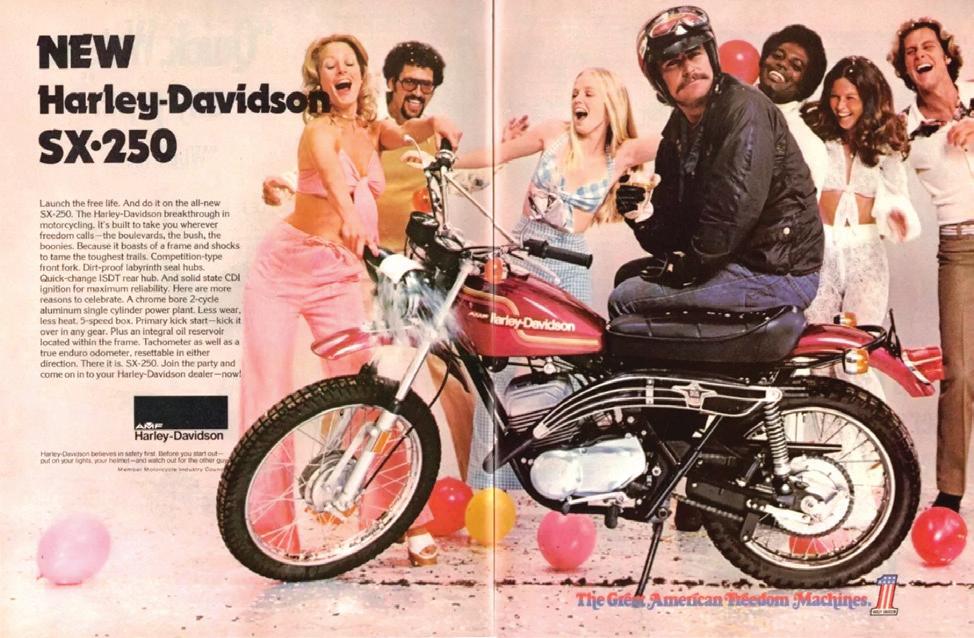

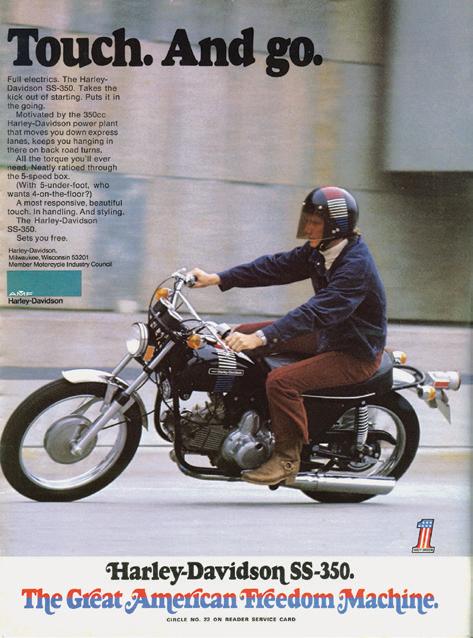

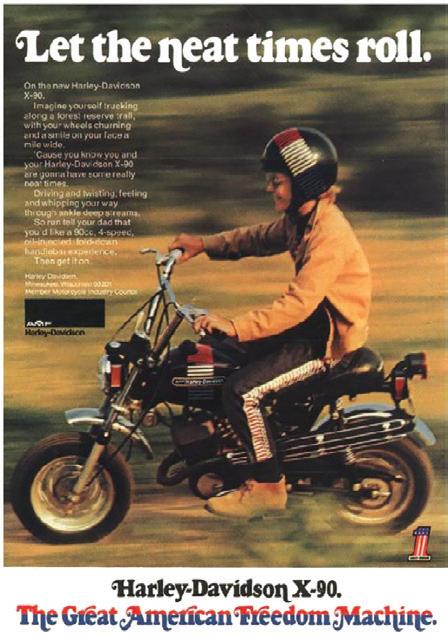

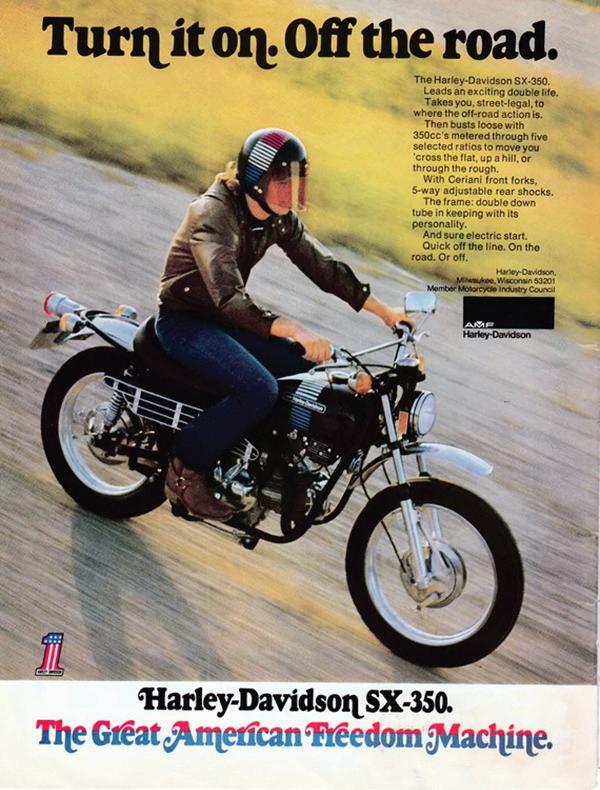

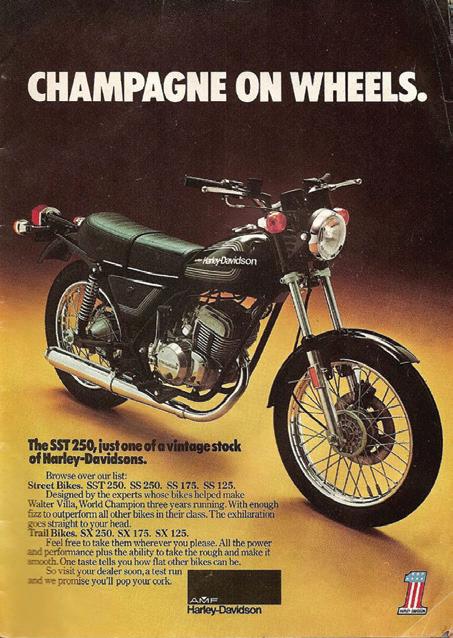

Harley-Davidson built some very interesting motorcycles in the 1970s, not least of which was Willie G.’s radical XLCR café racer (left) and the legendary, post-Easy Rider Super Glide (below). But up against the wave of cheap and reliable Japanese machines they didn’t resonate as much as they could have, which made the decade a challenging one in some ways for the Motor Company.

Despite the uncertainty and malaise of the latter 1970s, which included a crap economy (stagflation, layoffs, and higher-than-ever fuel prices) and a range of other unpleasantness, the Pinehurst group’s dual-track plan seemed pretty solid. Harley would be hedging its bets by diversifying its two-wheeled portfolio, and potentially expanding its customer base.

Development of both projects began soon after, with AMF funding things solidly. “You told AMF what you wanted, and you got it,” Beals told author Darwin

Holmstrom for his Harley-Davidson: The Complete History book. “They invested in major upgrades at Harley and let us hire lots of people.”

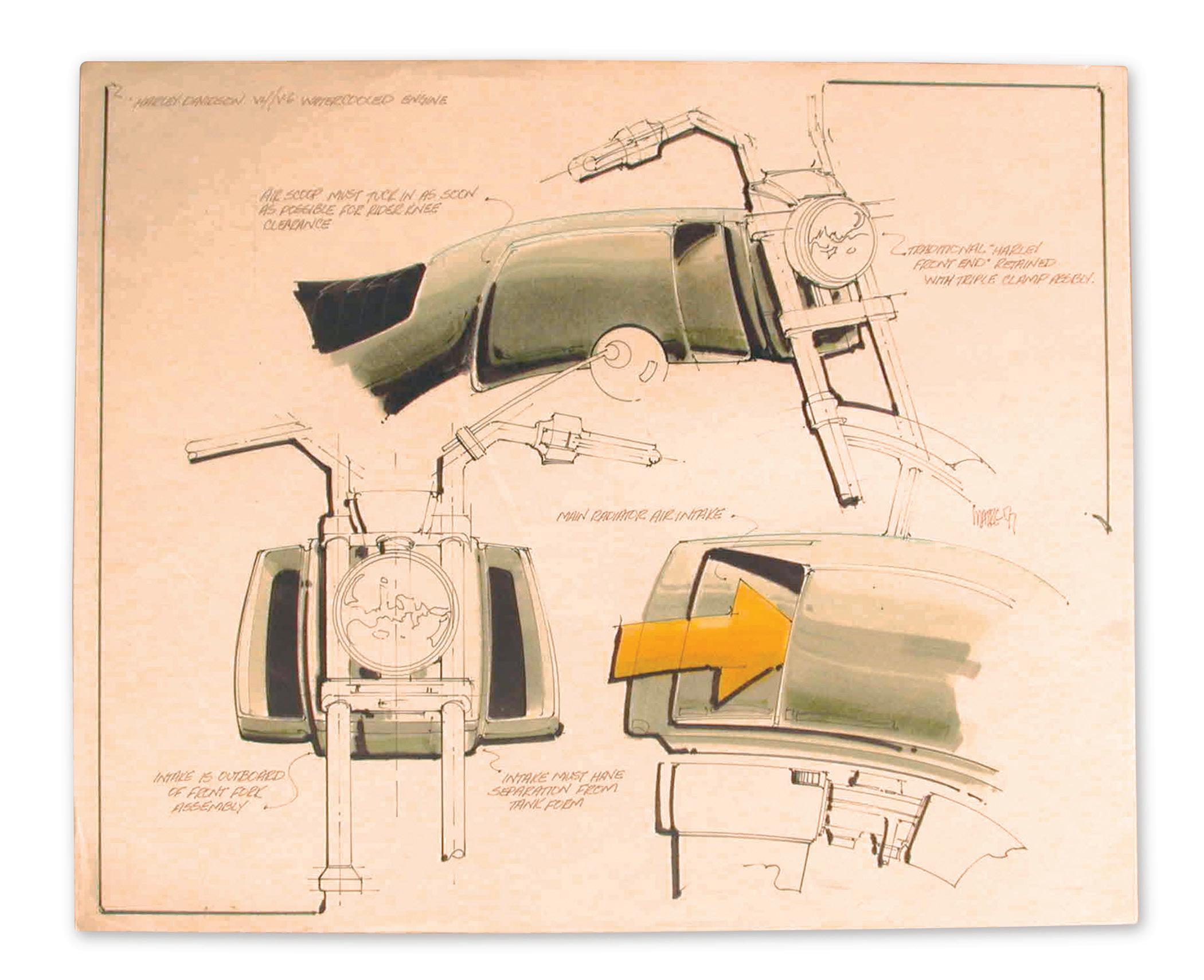

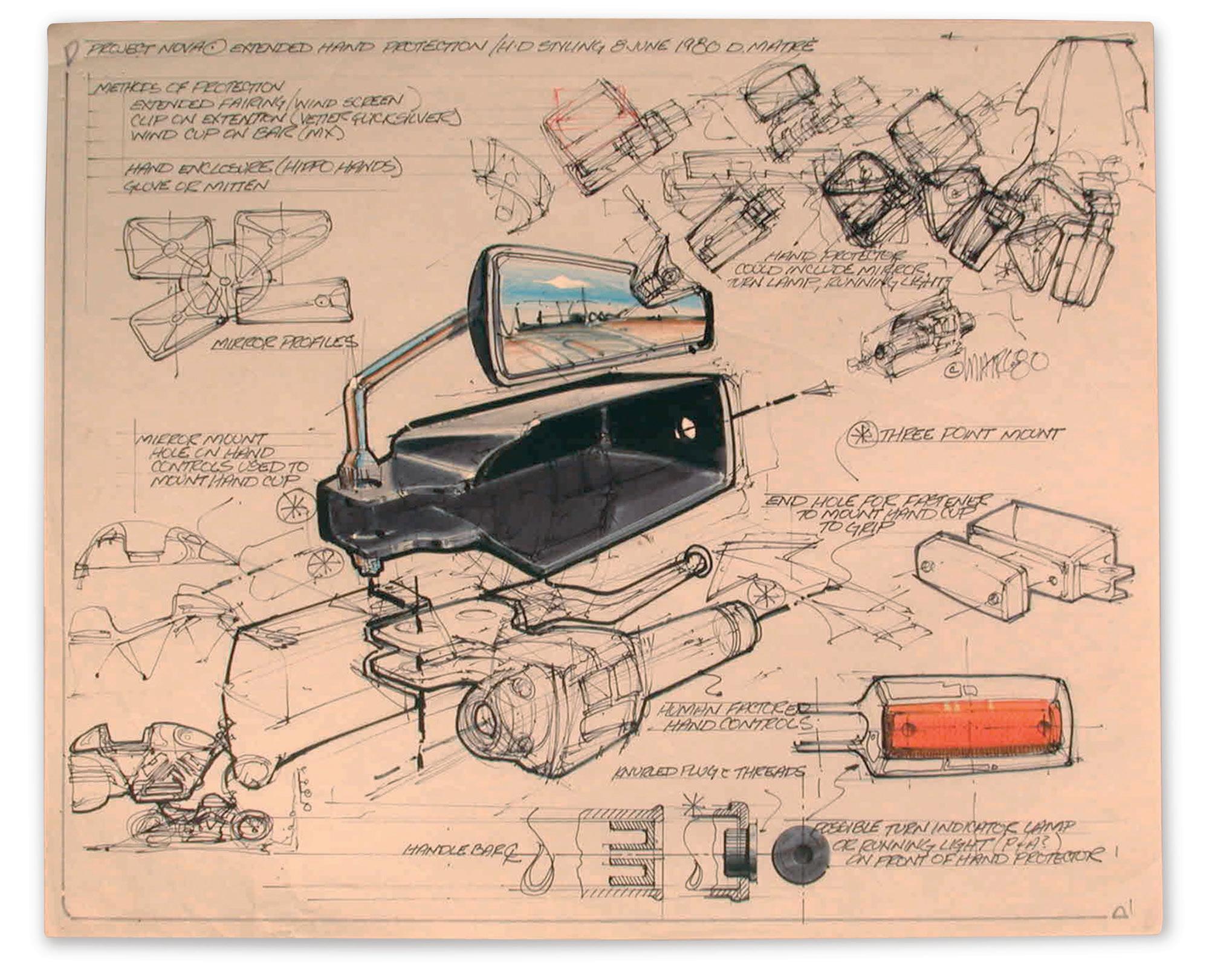

On the Nova side of things, Porsche was contracted to help design the new-generation engines (a partnership that would be re-established in the 2000s with the V-Rod powerplant), while chassis and drivetrain development would happen in Milwaukee. One of the more unique design elements the team came up with was the Nova’s underseat radiator system, which AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Legend Willie G. Davidson’s styling team encouraged so an ugly radiator didn’t muck up the bikes’ looks.

But big change was coming, much of it fostered by the retirement in 1978 of AMF Chief Rodney Gott, who was replaced by W. Thomas York, a financial guy with no real motorcycle experience and a much different take on how to run AMF’s businesses — H-D included. Suddenly, financing this dual-track development got tricky.

“It got harder to get money out of AMF,” Beals told Holmstrom. “York was a bean counter and had hired [an outside] firm to develop a strategic plan. They convinced him AMF should be half industrial and half leisure. At the time, AMF was about two-thirds leisure. [Harley was part of the leisure group. —Ed.] He tried to get to 50/50 by acquisition, leaving no cash. At the time we were one of 40 companies in AMF, but we brought in one-fifth of the revenue.”

THOSE 14 LETTERS ON EVERY HARLEY-DAVIDSON FUEL TANK STILL PACKED A LOT OF EMOTIONAL AND HISTORICAL PUNCH, BUT PERFORMANCE AND BUILD QUALITY JUST DIDN’T BACK THINGS UP.

Buzz Buzzelli, an ex-Harley-Davidson associate and, later, Editor of American Rider, explained things thusly in the August 2002 issue: “York ordered the expansion of the industrial side, and financed it with profits from the leisure side. Under this plan, Harley-Davidson, AMF’s largest profit generator, would become the cash cow, milked of capital to feed other business interests. The Nova project, considered expensive and risky, fell victim to the bottom line, and was terminated.”

“When York shut off the money,” Beals said, “I knew we were gonna die and take AMF with us.”

Beals felt strongly about Harley-Davidson and the Nova project and proposed to York that AMF get to 50/50 by selling companies (including Harley-Davidson), not acquiring more. York was apparently intrigued, which offered Beals the opportunity to develop a plan in which he and a handful of company execs (thirteen total) would purchase the company from AMF. The group needed a $1 million down payment to satisfy lenders, which was a challenge. But they found the cash, and in June of ’81 AMF sold Harley-Davidson to them for just over $80 million.

The so-called “Gang of 13” staged a celebratory ride from H-D’s York, Pa., assembly plant to Milwaukee to celebrate, but as Holmstrom wrote, “the group was apprehensive because they knew the reality that awaited them in Milwaukee. They were obscenely in debt, the company’s reputation was in tatters, the country was in recession, the company and its dealers were already overstocked with motorcycles they couldn’t sell, and the motorcycle market was in a death spiral.”

Beals and crew knew they needed to develop new products, be more efficient, and fix a host of other issues if they were to avoid their own death spiral, but developing new motorcycles was insanely costly, and cash was in short supply given the company’s debt situation. So Harley’s options were these: continue developing the Evolution V-Twin, or go Nova. They could not afford to do both, as much as they wanted to. As Buzzelli wrote, “The Nova was the long-range hope, the 10-year promise. But air-cooled twins promised the most immediate cash flow. And so the Nova died yet another death.”

Of course, nearly everyone with a pulse knows what was to come…sales, brand and financial success on a staggering scale, from the middle 1980s to the great economic downturn of 2008. A lot of elements contributed, including Harley’s ability to survive foreclosure during ’81, ’82 and ’83, when sales were ugly, and the effects of the Reagan-imposed over-700cc tariff. Things improved when the reliable, more powerful and no-longer-leaky Evolution Big Twin debuted for 1984. In ’86 sales improved again via the introduction of an Evo-engined Sportster, and the soon-to-be-best-selling Softail models a bit later.

And then, as the ’80s morphed into the ’90s, baby boomers returned to motorcycling in a huge way, many inspired by the two-wheeled experiences of their younger years and a simmering desire to own a certain motorcycle with those fourteen letters on the fuel tank. A continuing wave of Reaganera nationalism didn’t hurt, either, and by the mid-’90s, Harley’s sales, brand image and financial strength were enormous.

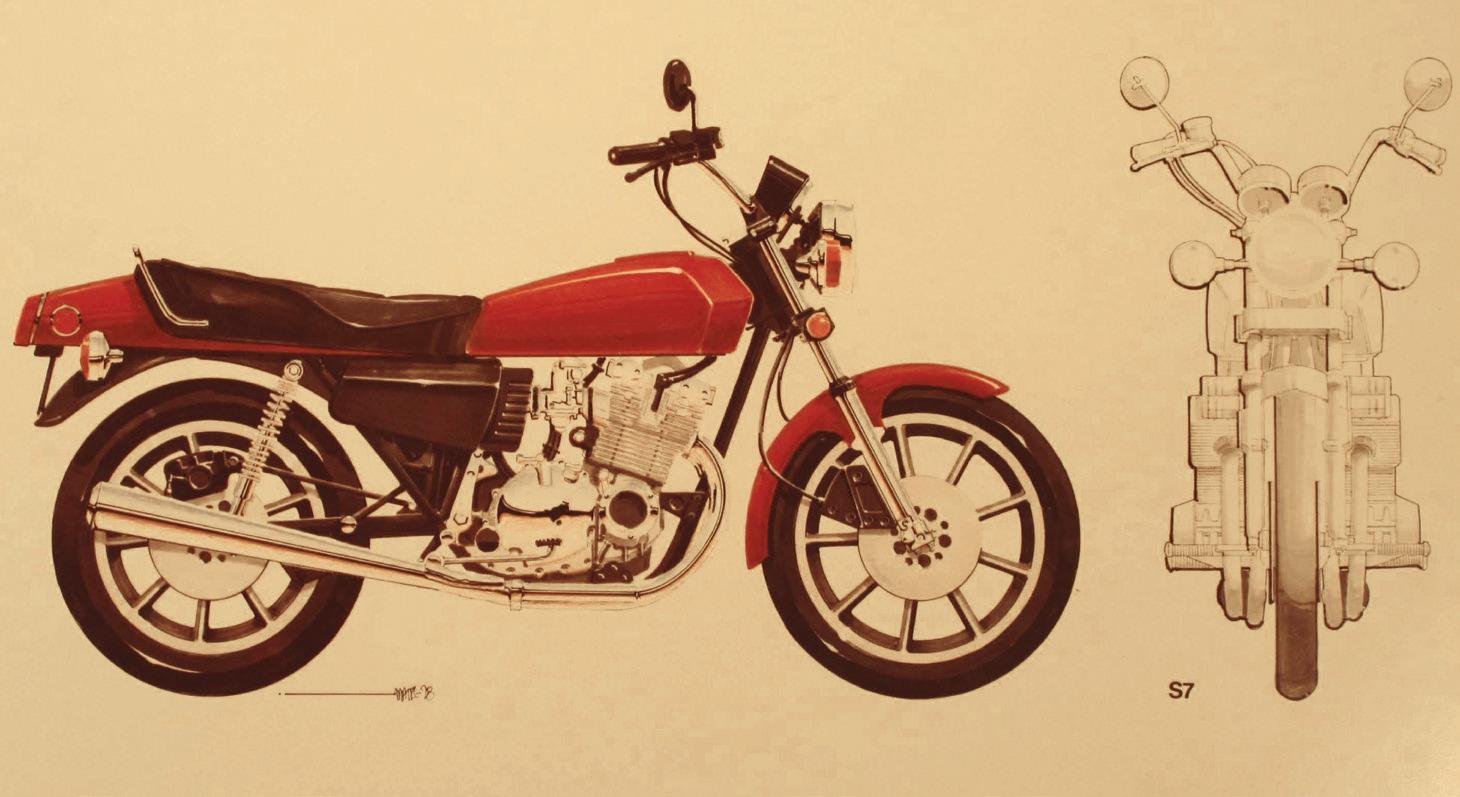

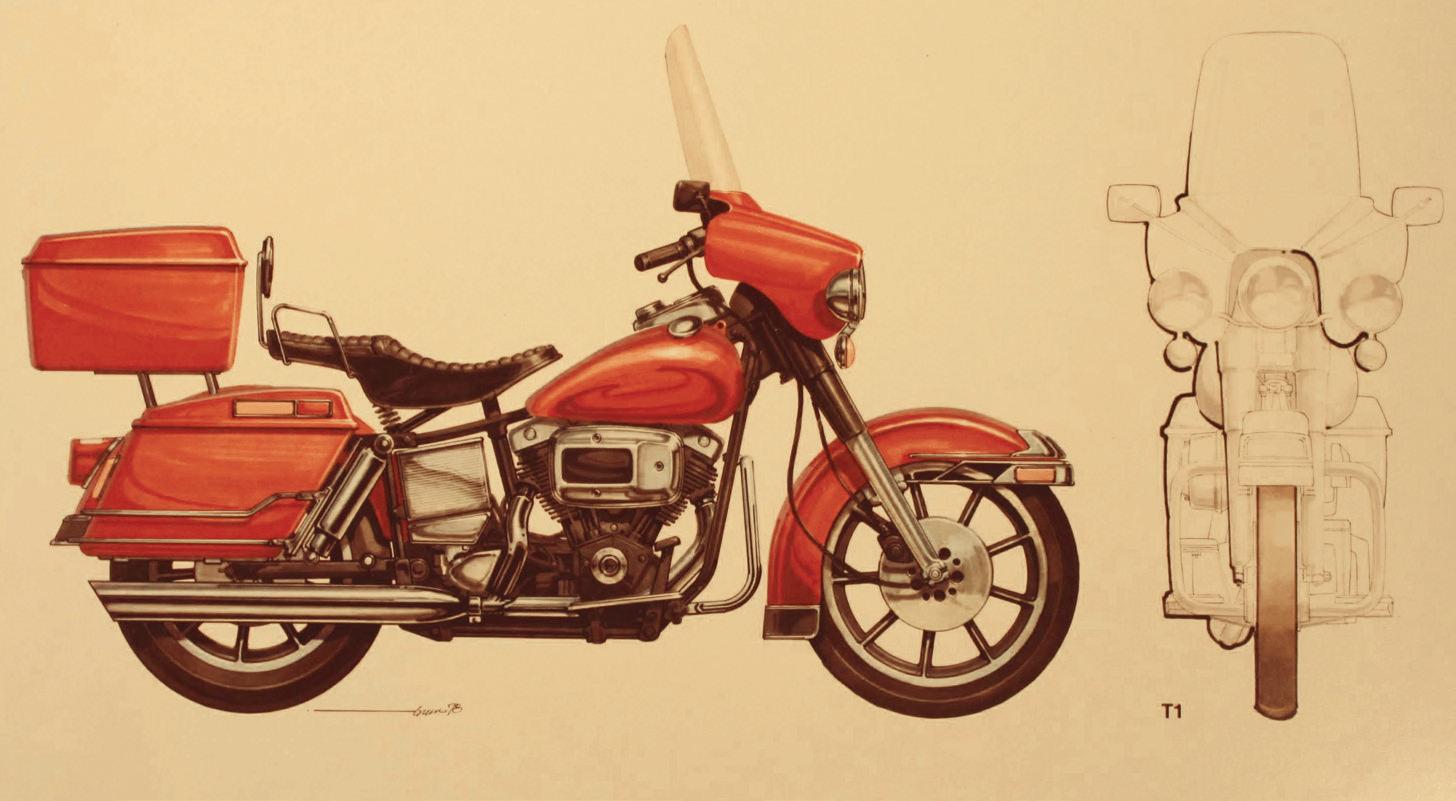

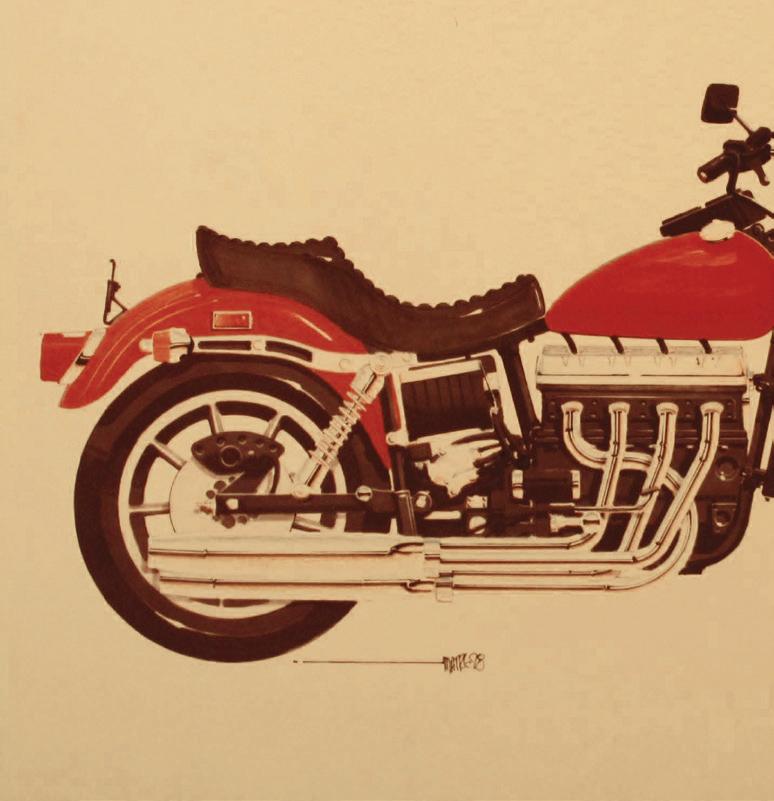

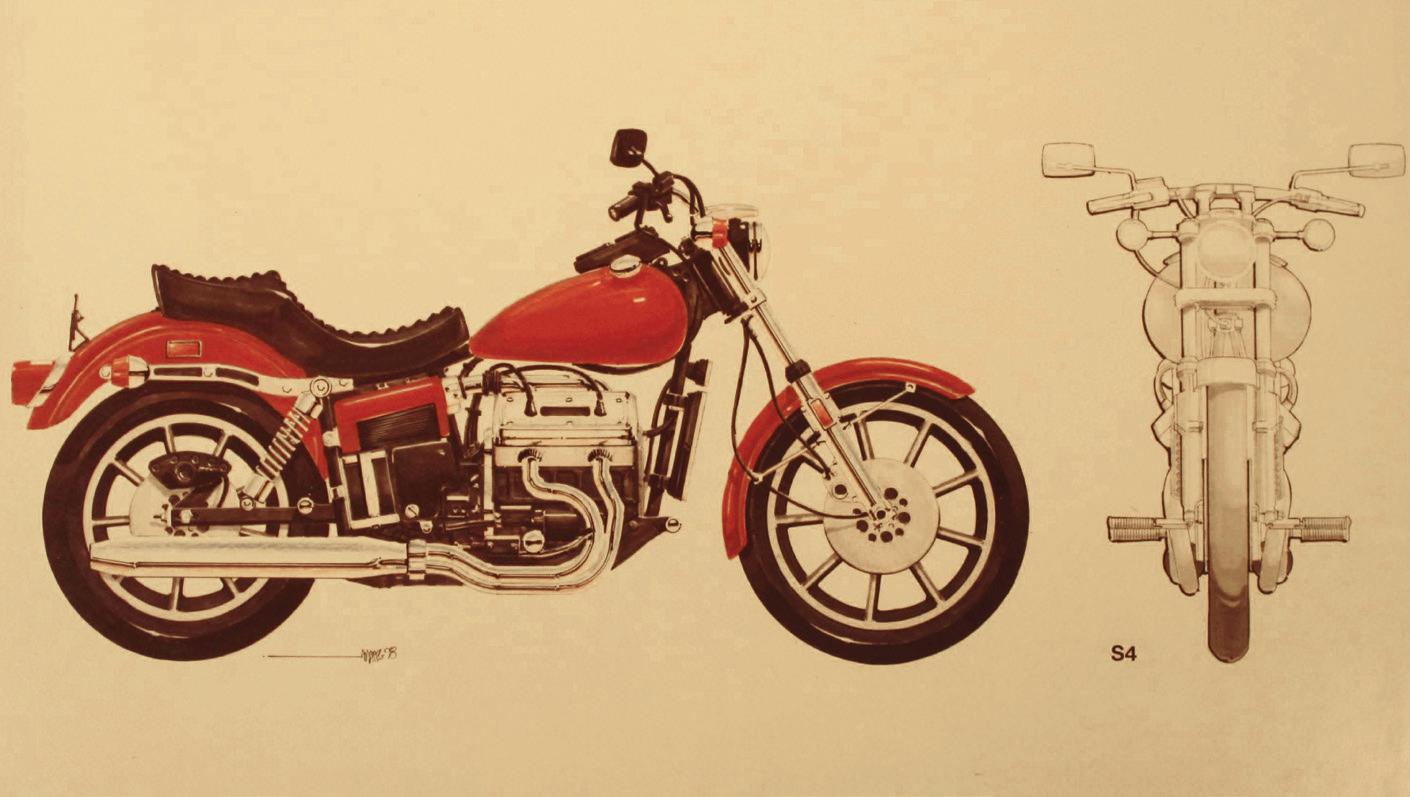

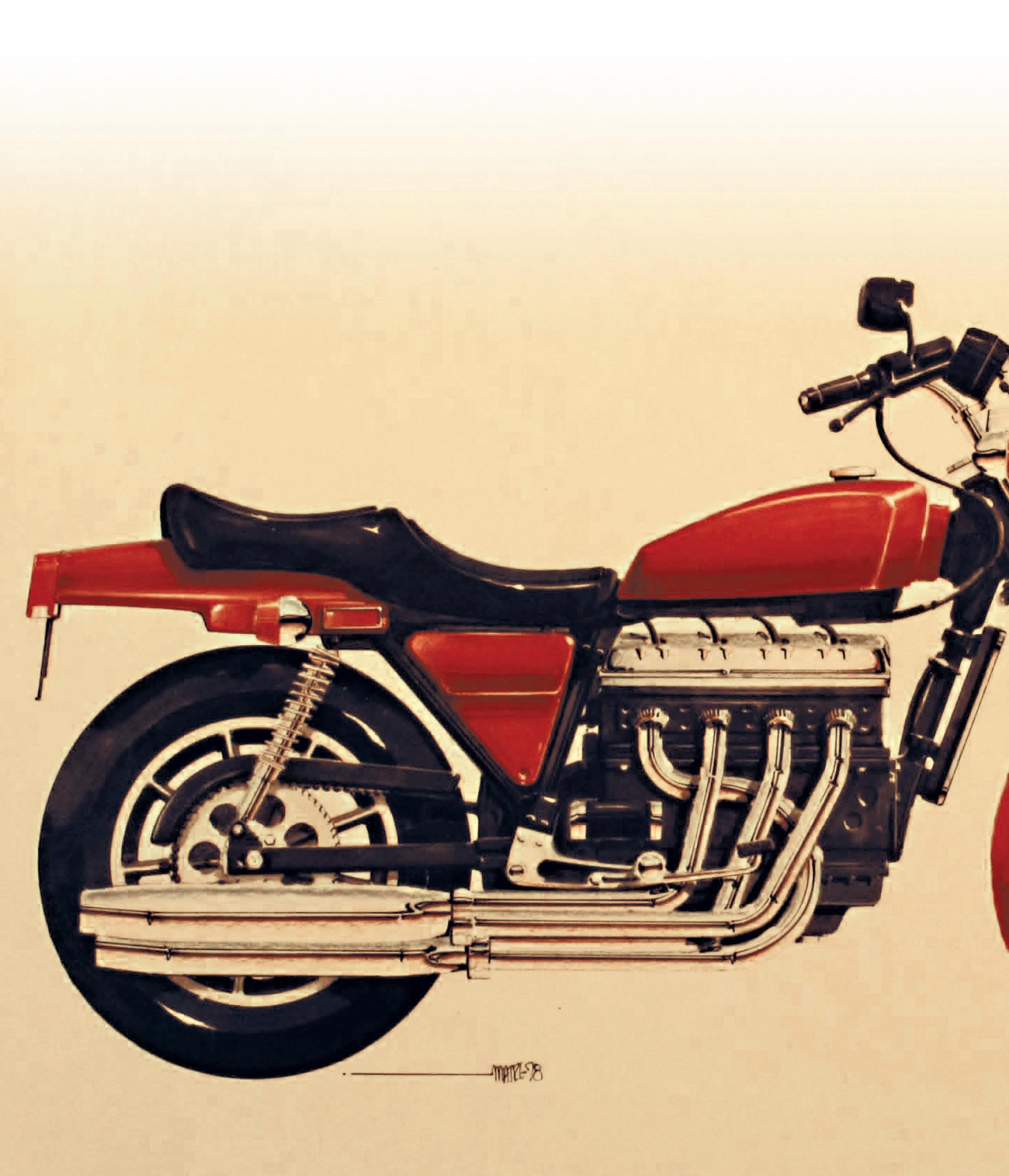

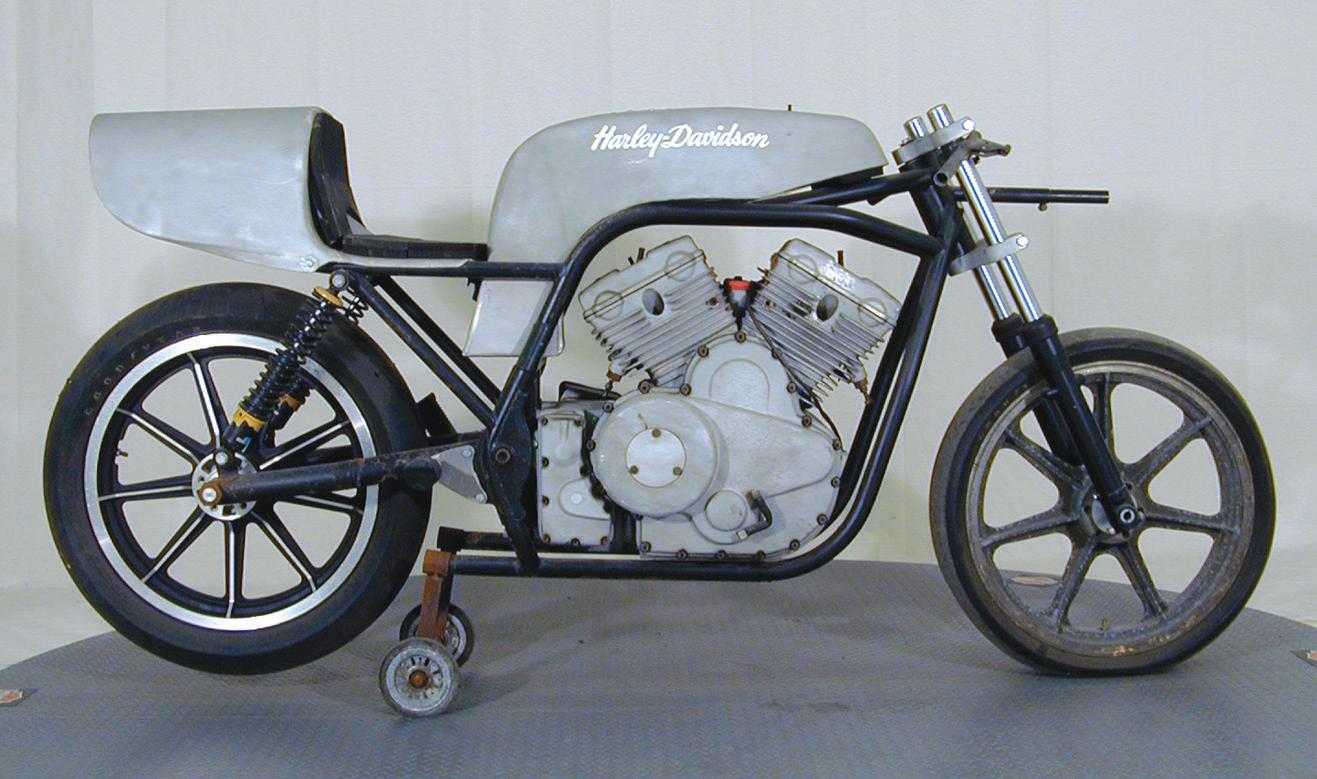

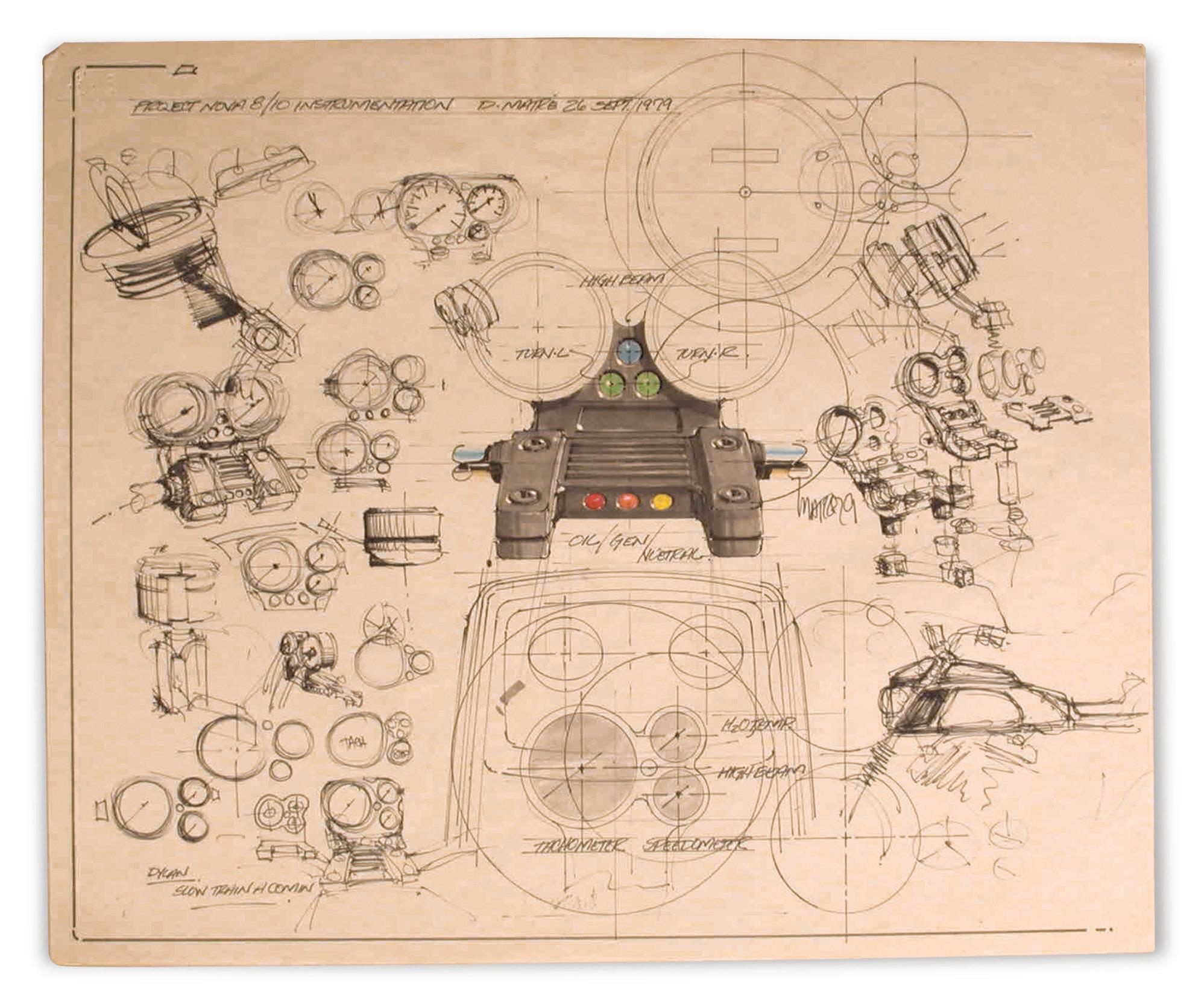

Early on, a wide range of Novas was envisioned, including sport cruisers (above, left), racebikes (above) and even a longitudinal-engined cruiser (left). By the time the project was killed, only V4 running prototypes had been built, with Porsche’s help. Left: American Rider’s August 2002 cover story.

So the suits got it right. But what if Milwaukee had built the Nova line and left the V-Twins to die? It’s an interesting question, but one with what many (this author included) feel is an absolutely ironclad answer.

Still, some feel the entire Nova experiment was an opportunity missed, a chance to have stuck it to the Japanese OEs and re-establish the industry dominance and if it was a key model, as these would have been, the result would have been devastating.

Second, this high-tech direction was relatively new to H-D engineering despite Porsche’s assistance, and getting right all the things you’d need to get right to compete with the technically-excellent Japanese would have been an uphill climb — at least for a while. Japan Inc., remember, had near-unlimited development funds, and was on the verge of introducing world-class chassis the Motor Co. once held. The end result would’ve set Milwaukee up powerfully in all sectors, they argued, not simply within the heritage/custom/traditional category Harley had traditionally dominated.

But there are chinks in that thinking. First, even without Evo development costs factored in, the company was seriously cash poor at the time, and developing highertech motorcycles, especially a handful of models with different engine displacements and three different cylinder configurations, would have been wildly expensive. Getting something wrong would’ve meant quick death for a model, and engine technology gleaned from its exposure to Grand Prix and AMA Superbike racing. Harley had basically zero experience here, and its Nova racebike prototype, with its old-school/’70s chassis design, pretty much proves the point.

Third is, well, exactly that: massive competition from Japan Inc., which was about to roll out handfuls of superbly engineered, good looking, fine handling, affordable and wickedly fast motorcycles in sport, sport touring, touring and custom guises during the 1980s. Anyone think that woulda been do-able for Harley right out

“I RODE AND TESTED A V4 NOVA PROTOTYPE. THAT WAS THE ONLY CONFIGURATION EVER BUILT. I CAN’T SEE HOW THE NOVAS WOULD HAVE BEEN SALES SUCCESSES, AND BELIEVE VAUGHN [BEALS] DID THE RIGHT THING SHUTTING THE PROJECT DOWN.” of the gate in the challenging economy of the middle and late 1980s? Not sure any OE could have pulled it off.

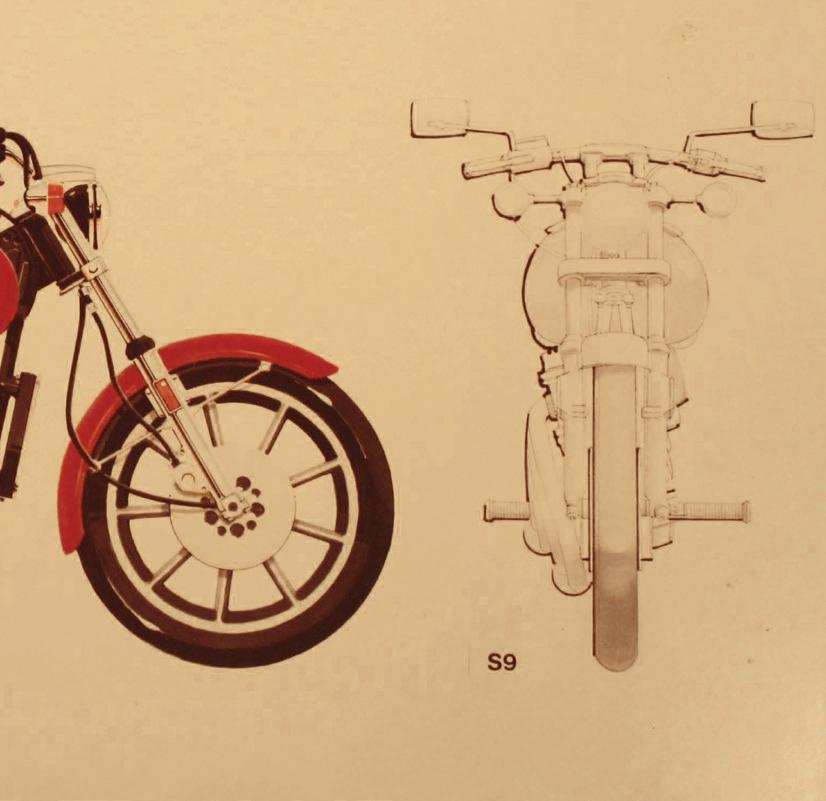

Styling- and category-wise, the Nova V4 prototypes ran the gamut, from Super Glide-esque (top) to sport-standard (left) to sport-tourer (below). Some interesting tech was in evidence, too; the future-think disc setup up front being a good example.

Finally, despite help from Willie G’s styling group, the handful of Nova prototypes in existence are — let’s be honest here — not overwhelming aesthetic successes. Some have called them butt-ugly, and while that’s all purely subjective, the Novas were not going to rival motorcycles like the Yamaha V-Max, Suzuki GS1150, Honda Magnas or Sabres, Kawasaki Eliminators or Ninja

“Harley hit the nail on the head with the Evo,” Burke told me, “and grabbed many of the customers we and Honda had captured in the ’60s and ’70s. They also put the social value back into motorcycling with the HOG chapters. Just brilliant. But I believe strongly that doing the Nova and not the Evo would absolutely have killed the company. Heck, even we had a tough time competing in the 1980s; it was a difficult market, for sure. If I remember correctly, Honda introduced 12 or 15 all-new models in 1983 alone; it was war back then!”

900, or any number of Japanese streetbikes, for looks or attitude. Sure, Harley-Davidson could have re-styled the Novas once the verdicts were in, but that would have taken more time and money, two things Milwaukee had very little of at the time.

Would the Novas have killed the Motor Company? Many think so, and this author certainly agrees. AMA Motorcycle Hall of Famer Ed Burke, who ran Yamaha’s product-planning for decades and who was responsible for some of the most successful sport, touring and custom motorcycles in history, agrees.

A discussion with Erik Buell, who worked in Harley’s engineering department after his racing career, and who developed and led the Buell Motorcycle effort from 1983 to its demise in 2009, confirmed a lot of this.

“The Nova project got started in 1977, I believe, and I started with Harley in 1979,” Buell said recently. “But there were no running bikes before I was there. As an engineer, I knew that product pretty well even though I wasn’t on the design team. I watched it slide from having some performance potential to being a slug, as it was committeed into oblivion. I don’t think it would have sold anyway; it wasn’t a Harley to the Harley market, and it couldn’t compete with imports in the performance market.”

“I rode and tested a V4 Nova prototype,” Buell added. “That was the only configuration ever built. The V2 and V6 were on-paper only. Though I wasn’t on the project per se, I was doing vehicle performance testing on all products. There was some innovative stuff in the bike, but the design had been compromised by some Harley- and history proves it. The decision may have been largely financial, but the old adage of sticking with what you know and doing it right certainly paid dividends — for the Company as well as for Harley-Davidson fans. What’s so interesting — and certainly ironic — about all this are the parallels with today. Once again, just as in the middle and late 1970s, Harley-Davidson finds itself needing to expand its reach and scope to younger, nontraditional buyers, and is doing so in ways that very much izing of the initial concept, which was why the weight and cornering clearance problems existed, but also the cooling-system concept had some significant flaws. It was not fast. Smooth, yes, but pretty heavy, with very little cornering clearance. I came close to putting one into the Armco while testing on the Talladega road course when the pipes dragged and levered the wheels off the ground. I can’t see how the Novas would have been sales successes, and believe Vaughn [Beals] did the right thing shutting that project down.”

So in the end, Harley-Davidson chose the right path, mirror what the Pinehurst Plan called for – high-tech, liquidcooled and less-traditional motorcycles like the Pan America adventure tourer and Nightster cruiser. This time, however, the company has the financial and engineering might to do that job.

I think those suits in the boardroom would be proud, and the late Mr. Beals, especially.

…Two roads diverged in a wood, and I — I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. All the difference. AMA