8 minute read

Steven Surina – Diving Instructor, Underwater Videographer, Lecturer and Naturalist Guide

FEATURE STEVEN SURINA TRANSLATED FROM FRENCH ALLY LANDES FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHERS GREG LECOEUR, SYLVIE AYER, FABRICE BOISSIER, DAVID GUILLEMET, THOMAS BAECHTOLD AND FABRICE DUDENHOFER

Advertisement

BIOGRAPHY

Born in the Parisian suburbs in 1988, Steven Surina expatriated to Egypt in 2002. Born into diving from the age of six, he grew up in a dive club run by his family where the Red Sea opened the gates of exploration into Djibouti, Sudan, Eritrea and Saudi Arabia. He has travelled the world in developing his career and has been diving with sharks more than 500 times a year since 2008.

Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) by © Greg Lecoeur.

CAREER

His many varied trips have led him to dive with thousands of sharks, and in doing so, instilled a deep fascination to study their behavioursHe has experienced dozens of cage-free dives with the great white shark, has spent hundreds of hours alongside tiger and bull sharks, and has had over a thousand dives in daily contact with the oceanic whitetip shark.

Steven is a scuba diving instructor, underwater videographer, lecturer and naturalist guide, and the founder and manager of ‘Shark Education’, founded in 2011, where he specialises in shark ethology (the interactions between divers and sharks). He is very active in his conservation work and shark eco-tourism, in which he regularly organises conferences and seminars in France.

To share his experiences, Steven offers specially tailored dive excursions for divers to meet with differentsharkspecies from aselection offifteen destinations around the world (Egypt, Sudan, Djibouti, Maldives, Philippines, Mozambique, South Africa, Bahamas, Mexico etc.).

Bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) by © Sylvie Ayer.

With ‘Shark Education’, Steven works in partnerships with scientists and experts from around the world and also collaborates with various organisations such as the ‘Bimini SharkLab’ in the Bahamas, ‘Ichtoconsult’ of the IRD, ‘Saving our Sharks’ in Mexico, and takes part in the population monitoring shark programmes in Sudan after having joined the ‘Divers Aware of Sharks’ network from the Cousteau Society.

Bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) by © Sylvie Ayer.

Steven is one of the few French divers to have mastered tonic immobility on several species of sharks in the wild, using various techniques in order to remove fish hooks.

A scientist in the making, he also conducts his own research by following an EPHE diploma supported by Shark Specialist, Dr Eric Clua, a professor of Marine Biology.

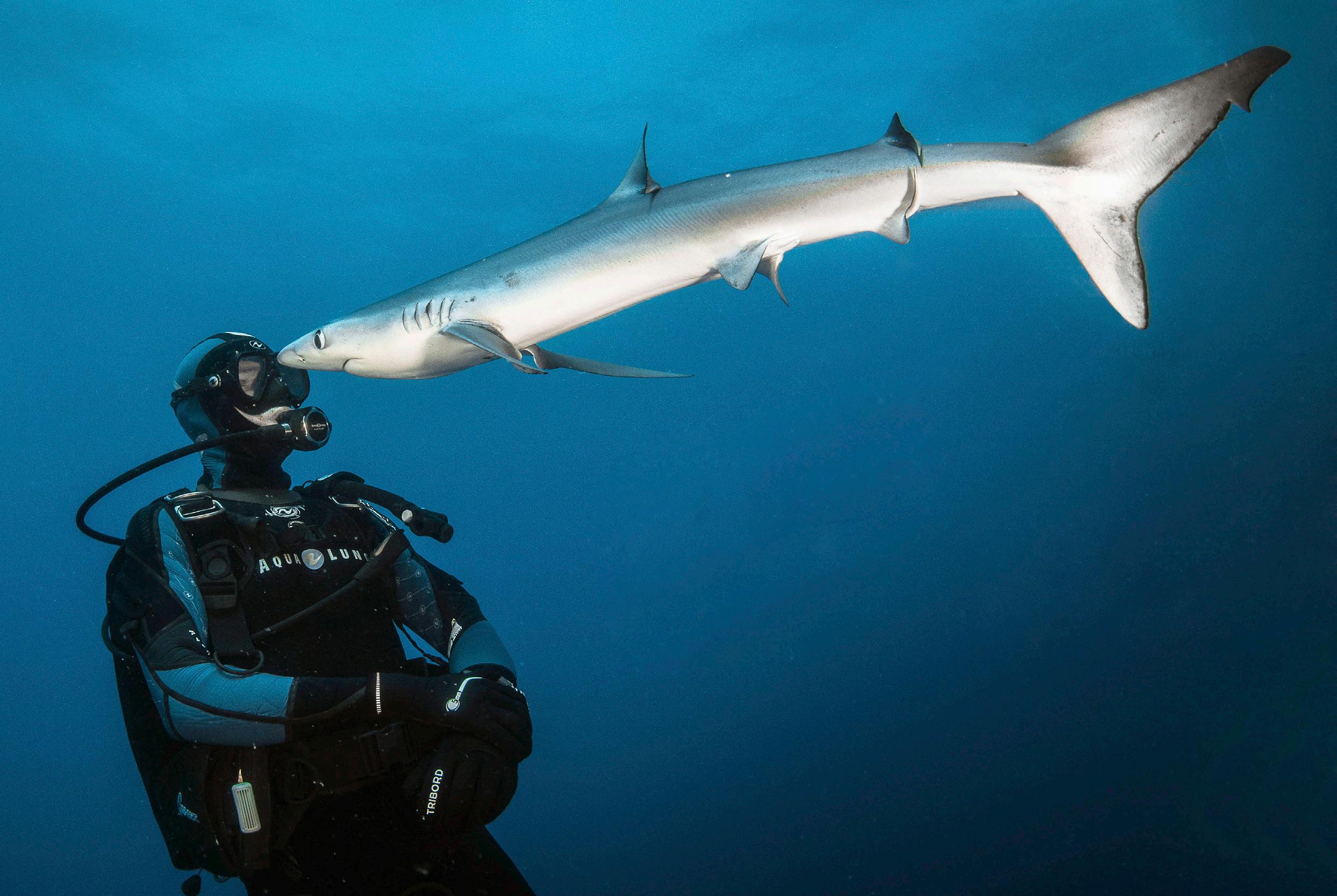

Blue shark (Prionace glauca) by © Fabrice Boissier.

Steven has published three books on human-shark interactions (currently only available in French):

1. Comprendre et Plonger Avec les Requins (Turtle Prod: 2015)

2. REQUINS – Guide de L’interaction – Avec le Photographe Greg Lecoeur (Turtle Prod: 2017)

3. Rencontres Avec Les Requins – Avec le Dessinateur Cyril Girard (Turtle Prod: 2019)

In 2016, he created the first study on the behaviour of Red Sea and Indian Ocean sharks, and with Dr Seret in 2017, created the first International Char ter for Responsible Shark Ecotourism.

In 2018, he took par t in the filming of‘Shark Wave’, a documentary produced by Patrick Metzlé where he took famous French director Jan Kounen out to dive with oceanic sharks of the Red Sea. In 2019, in the film ‘Au Nom Du Requin’ commissioned by the Salon International de La Plongée Sous-Marine, he took François Sarano diving alongside the bull sharks of Playa Del Carmen in Mexico.

Steven was asked to showcase and present this year’s dive show theme, the “New Generation of Divers” at the 22 nd Salon International de La Plongée Sous-Marine in Paris from the 10-13 of January.

Blue Shark (Prionace glauca). Photo by © Greg Lecoeur.

HIS OBJECTIVES

To demonstrate that it is possible to interact with sharks by promoting responsible ecotourism and above all, train divers to protecting sharks by converting them into ambassadors.

HOW?

By demystifying peoples’ misunderstandings and fears by offering a new outlook and experience of diving with sharks, combining practice and theory thanks to daily conferences presented during his customised expeditions.

Great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran). Photo by © Greg Lecoeur.

WHY?

Steven grew up amongst a family of divers. At the age of 5, he first discovered great white sharks in a documentary by Jacques Cousteau. He was as terrified as he was fascinated. Over time, his fear and curiosity became an inquisitive mix of emotions that developed his true passion for sharks today. As soon as he was given his first oppor tunity to enter into their environment at the age of 9, his one and only motivation was to come face to face with them. His excitement and ecstasy was followed with admiration, wonder, enthusiasm and the trance in which each encounter put him in, was incredible! He was the luckiest kid.

However, becoming a professional diver with the vocation to protect sharks, was not his initial calling. As he was growing up, it was the ignorance of other divers surrounding this species that caught his attention. It was easier to get away from sharks than it was to attract them. What I noticed from my interactions with people, was divers’ awkwardness when they were in shark territories. They did not have the right codes of conduct, and their interactions were mostly stealthy.

In the earlier years, his studies weren’t entirely successful and he felt he needed to emancipate himself and fast. He was 18 when he first became a diving instructor on livaboard cruises in Egypt. An opportunity that allowed Steven to be in regular contact with sharks in order to study them.

Over time, those experiences and the enrichment he got from his daily life shared with them, he found the essential need to show sharks in a completely different angle than that of them depicted as dangerous animals. Steven was clearly inspired by the film ‘Shark Water’ (2006) by Rob Stewart, and the genesis of ‘Shark Education’ took shape.

Steven using a technique of tonic immobility. Photo by © David Guillemet.

COMBINING SHARK PROTECTION AND UNDERWATER ENCOUNTERS

What he found to most suit his principles was conservation, education and interaction. It was a positive move forwards and these were the founding pillars of Shark Education.

With the growing development of ecotourism, it became clear that his commitment was to encourage as many people as possible to interact with sharks, by discovering new observation methods, and combining both theory and practice. There are two types of environmentalists: the passive and the active. Steven believes that when someone is moved by a gift from nature, the question no longer hangs on whether to act or not, because that desire to share this affection with others and future generations surpasses the strongest ecological commitments.

When a shark approaches you and grants you 30 seconds or 30 minutes of its time, it is also observing you, and perhaps trying to communicate with you. This immense gift made to you by this wild, untamed animal reminds you that if it were not for this experience, such an interaction with a terrestrial predator would otherwise be impossible. I love to dive with sharks because you can’t cheat. It’s always when we least expect them that they put us back in our place and bring arrogance back to humanity. The mirror effect is immediate and the only words that come to mind are respect, love and humility.

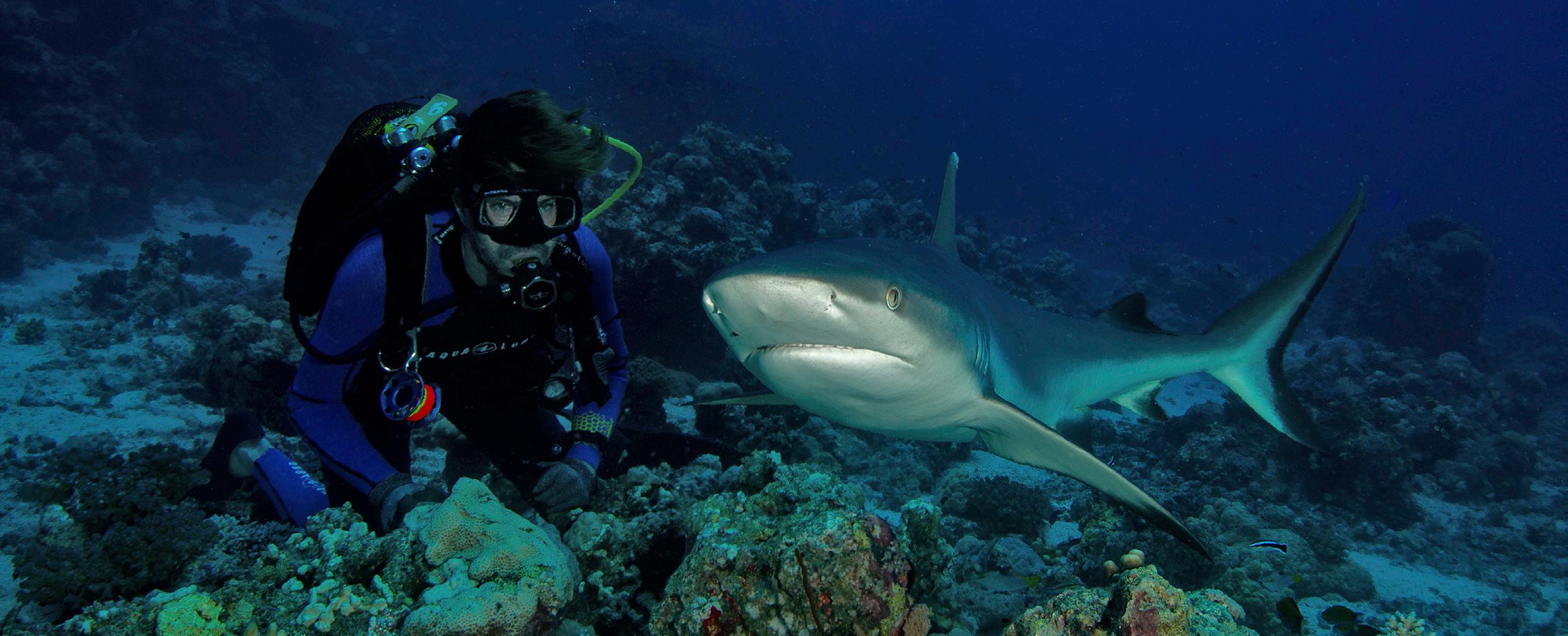

Grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos). Photo by ©Thomas Baechtold.

Everything I have today, everything that has shaped my personality, everything that allows me to live the life I have chosen, I owe to sharks. Without them, I would not have the lifestyle I have to date. Protecting them is more than a commitment, it is a necessity. On a larger scale, it is the salvation of life on Earth that depends on it. The legend of the hummingbird (a Native American legend) always remains more effective than not taking any action at all. Things don’t get worse by the people who do us harm, but by those who do nothing.

Broadnose sevengill shark (Notorynchus cepedianus). Photo by © Fabrice Boissier.

FACTS

Today, sharks are a fashionable phenomenon. Endlessly feared by man, they continuously inspire fascination. Thanks to social networks, television or sensitised media personalities, more and more people are helping to restore sharks’ reputations.

More countries are protecting them by creating sanctuaries. Science is becoming more and more interested in them, and sharks have turned into business and tourist attractions where the plight is now to save them from disappearing. The popular craze surrounding these so-called “man-eaters” has taken a setback which probably linked to their decline in numbers, and has finally changed mentalities in the interest of the urgent need to protecting them. It’s a good thing to want to change their image from monsters. It should not however be forgotten that sharks remain wild, and unpredictable predators. To dive alongside them is accessible to anyone, as long as you are accompanied by professionals and respect the strict safety instructions. Above all, the ocean must not turn into a zoo where sharks become a fairground phenomena.

“I am thrilled to see we no longer“fight” alone and that this enthusiasm affects all generations, but I am disappointed to see certain practices are taken to extremes, or that certain images of reality are completely distorted.”

Steven Surina, selfie.

HOPES

The disappearance of sharks is becoming more and more apparent, but Steven has been lucky enough to witness few changes in the quantity/density of sharks he has seen. The populations of sharks living in the areas where he frequently dives seems to be less affected by fishing, even for migratory animals. There are of course certain regions or seasons more prolific than others over time, but he has never had the misfor tune to see a significant or progressive disappearance in those areas familiar to him. Which in twenty years, is rather encouraging.

Steven Surina portrait by © Fabrice Dudenhofer.

In addition to the awareness needed to defend sharks, more and more initiatives are being implemented, even if some seem very delayed for the conservation of certain endangered species. Even while there is still a long way to go and the preservation objectives are still insufficient, the observations seem less dramatic than those from the early 2000s. It is important not to lose hope, know that resources are not inexhaustible, that the situation remains critical, and the urgency is very much absolute!